The Living Legacy Of The Cheyenne

The Cheyenne were once one of the most powerful tribes on the Great Plains, but they had to fight hard to stay at the top. They first proved themselves against other Native tribes, but when the United States Army came knocking, they cemented a reputation as fearsome warriors and protectors of the Plains. The Cheyenne’s fight to make a home on the Plains would eventually see them become masters of adaptation—and influence the course of American history.

Their Origins

Today’s Cheyenne are the descendants of two tribes that merged in the mid-19th century: the Tsitsistas and the Suhtai. Both tribal sects have origin stories involving their own unique prophets who received divine gifts from Ma'heo'o, the Great Spirit.

Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images

Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images

Their Population

Today, there are approximately 22,970 Cheyenne people divided between two recognized nations: the Northern Cheyenne in Montana and the Southern Cheyenne in Oklahoma.

Visions Service Adventures, Flickr

Visions Service Adventures, Flickr

Sweet Medicine

Historically, the Tsitsistas’ prophet was called Sweet Medicine and the Great Spirit gifted him with the Sacred Arrow Bundle. He received this gift in South Dakota, at the top of Medicine-Hill, known to non-natives as Bear Butte.

JERRYE & ROY KLOTZ MD, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

JERRYE & ROY KLOTZ MD, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Sacred Arrows

Sweet Medicine brought the sacred arrows to the Cheyenne and they used these divine weapons when they fought against other tribes. During times of peace, the arrows were kept in an arrow lodge called a “maahéome”.

Sailko, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sailko, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Building A Society

In addition to arming the Cheyenne, Sweet Medicine organized how their society was built, created a legal system, formed military societies, and created the Council of Forty-four, who ruled during peacetimes.

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

The Council Of Forty-four

The Council of Forty-four was made up of four chiefs, or “véhoo'o”, from each of the 10 main bands, called “manaho”. They were joined by four “Old Man” chiefs who had served honorable on the council before.

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

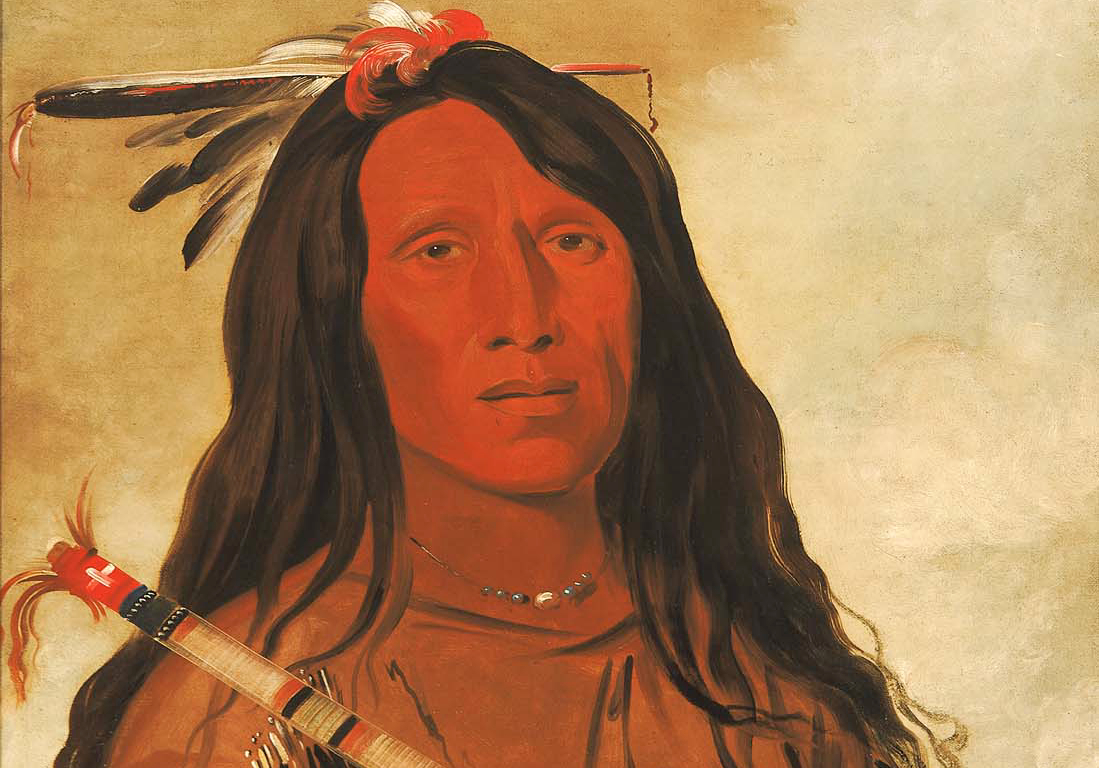

Erect Horns

The Suhtai prophet was called Erect Horns, and Great Spirit gifted him with the Sacred Buffalo Hat Bundle. Erect Horns received this gift on Stone Hammer Mountain, located near the Great Lakes of Minnesota. The Sacred Buffalo Hat Bundle was kept in the Sacred Hat Lodge, called a “hóhkėha'éome”.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

Predictions

Sweet Medicine is said to have predicted that the arrival of the horse, the cow, and the white men to the Cheyenne. Erect Horns also predicted the coming of the horse, and is thought to have convinced the Cheyenne to abandon their sedentary lifestyle for a nomadic one.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

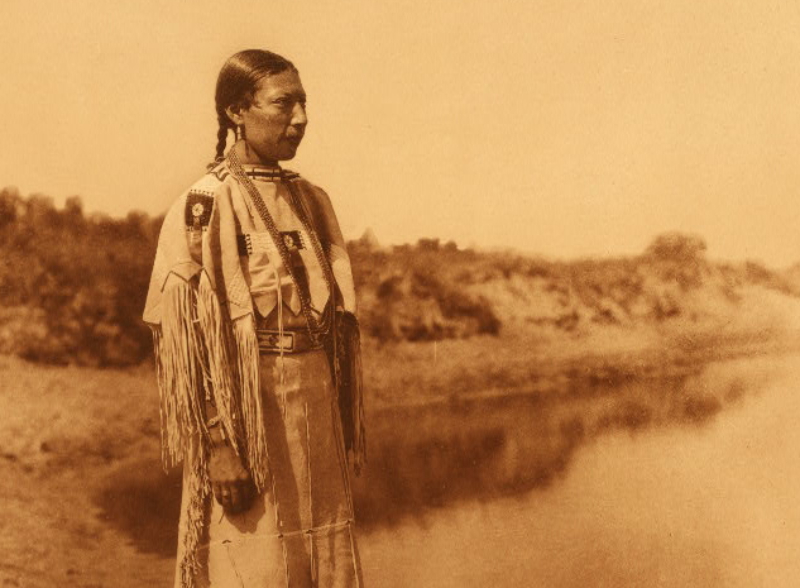

Two Halves Of A Whole

In Cheyenne myths, the Sacred Arrows represent male power, while the Sacred Buffalo Hat is a symbol of female power. It is thought that through the two bundles, Great Spirit ensures the continuation of life and blessing for the Cheyenne.

Edward S. Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

Edward S. Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

The Sacred Buffalo Hat

According to tradition, the Sacred Buffalo Hat was kept with the Sacred Buffalo Hat Keeper. The Keeper must be a member of the Northern Tsitsistas and Suhtai tribes. Today, the Sacred Buffalo Hat is kept safe by the Northern Cheyenne, but it was almost lost to the sands of time.

Balkowitsch, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Balkowitsch, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Was A Bad Keeper

In the 1870s, the Sacred Buffalo Hat Bundle was in the car of keeper Broken Dish. But the tribal leaders began to doubt Broken Dishes ability as a sacred keeper and asked that he give up the sacred bundle. Broken Dish agreed, but his wife had other plans.

She Lost It

Broken Dish’s wife was furious with her husband’s decision to give up the bundle. In her anger, she desecrated the sacred bundle, and the ceremonial pipe and buffalo horn within it were lost for several years.

Curtis, Edward S., Wikimedia Commons

Curtis, Edward S., Wikimedia Commons

The Missing Piece

Luckily, in 1908, a Cheyenne named Three Fingers found the horn and returned it to the Sacred Buffalo Hat Bundle. A Cheyenne name Burnt All Over acquired the ceremonial pipe, but it would not be reunited with the rest of the bundle until decades later.

BPL, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

BPL, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Changing Hands

Burnt All Over gave the pipe to a woman named Hattie Goit, who lived in Poteau, Oklahoma. In 1911, Goit gave the pipe to the Oklahoma Historical Society. The Historical Society kept the pipe until 1997, when they negotiated the return of the pipe to Sacred Medicine Hat Bundle keeper James Black Wolf.

Elbridge Ayer Burbank, Wikimedia Commons

Elbridge Ayer Burbank, Wikimedia Commons

What Do They Call Themselves?

Today, the Cheyenne call themselves “Tsitsistas”, which means “the people” or “those who are like this”. The name “Cheyenne” is thought to have come from the name the Lakota Sioux gave the tribe, “Šahíyena”.

Helen H. Richardson, Getty Images

Helen H. Richardson, Getty Images

Their Language

The Cheyenne language is an Algonquin language, commonly called “Tsisinstsistots”. There are slight differences between the dialects of the Cheyenne language spoken in Montana and Oklahoma, but regardless of region, there are 14 letters in the Cheyene alphabet.

Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images

Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images

The Sun Dance

The Sun Dance is a sacred tradition among many Plains peoples, including the Cheyenne. According to their legends, the Sun Dance was given to the Cheyenne by their prophets, Sweet Medicine and Erect Horns. Traditionally, the Sun Dance took place once a year, when the buffalo returned to the plains after winter.

Henry Chaufty, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Chaufty, Wikimedia Commons

A Painful Tradition

While the name is pleasant enough, the Sun Dance is a harrowing experience for the dancers. They endure physical and spiritual tests by fasting for days while exposed to the elements. In some cases, they would fasten themselves to a pole with rawhide rope attached by piercing their chest. Then, they would dance around the pole.

Sacrifice

The torment that Sun Dancers go through is seen as an offering or sacrifice for their people. Usually, the dancers’ family members stay in a camp nearby and support them with prayer.

Keep It Secret

Outsiders still don’t know much about the specific origins and details of what happens during the Sun Dance. That’s because most tribes forbid the ceremony to be filmed or photographed.

Cheyenne Romance

Historically, Cheyenne courtship took years, since men had to prove themselves by acquiring a herd of horses and a reputation as a respected warrior. Marriages were often arranged by the families of the betrothed. There was little shame around divorce, which could be initiated by either party for adultery, mistreatment, or other marital grievances.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Their Homeland

According to the Cheyenne’s tribal history, they used to live in the Great Lakes region until they were pushed off their lands by the Assiniboine. Around 1676, the Cheyenne eventually settled in what we now call Minnesota and North Dakota, building villages between Mille Lacs Lake and the Mississippi River.

What Did They Eat?

During this time, the Cheyenne relied on their knowledge of the land to find food. They foraged for wild rice, potatoes, turnips, and berries. They also hunted game like deer, wild turkey, and rabbits. It’s believed that the Cheynne also learned to ride horses around this time, which improved their ability to hunt buffalo.

Missouri History Museum, Picryl

Missouri History Museum, Picryl

Tides Of Change

The Cheyenne enjoyed just under a hundred years of peace in Minnesota’s Mille Lac region. But everything changed around 1765. That’s when the Ojibwe finally defeated the Dakota, pushing them off their lands. The Cheyenne got swept up in that push.

Julian Vannerson, Wikimedia Commons

Julian Vannerson, Wikimedia Commons

Searching For A New Home

The Cheyenne were forced to relocate to the Missouri River. There, they met the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara people. The Cheyenne took on some of the cultural characteristics of these neighboring tribes but continued west in search of a new territory. They found it in the Black Hills.

Runner1928, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Runner1928, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Weren't Alone

Unfortunately, the Cheyenne’s time in the Black Hills was short lived. They weren’t the only ones vying for territory and found themselves frequently facing off with migrating groups of Lakota and Ojibwe.

Personal collection, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Personal collection, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Couldn't Win

By 1776, skirmishes with neighboring tribes had taken their toll on the Cheyenne and they lost much of their territory in the Black Hills to the Lakota. By the early 1800s there were only a few Cheyenne villages left in what we now call North Dakota.

Allies

The Cheyenne began to establish a new territory for themselves, but they knew that if they hoped to keep this new ground and expand, they would need some help. Around 1811, the Cheyenne formed an alliance with the Arapaho people. That alliance still remains strong to this day.

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

Moving Up In The World

With the help of the Arapaho, the Cheyenne were able to expand their territory. It went from southern Montana through to most of Wyoming, eastern Colorado and the far western parts of Nebraska and Kansas.

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

Strange Encounters

By 1820, the Cheyenne had had several encounters with American traders and explorers. Most of these meetings took place near Denver, Colorado, and it was common for the Cheyenne to trade bison meat and clothes for guns and tobacco from the Americans.

John H. Fitzgibbon, Wikimedia Commons

John H. Fitzgibbon, Wikimedia Commons

Bent's Fort

In 1833, Charles Bent constructed Bent’s Fort in southeastern Colorado. Bent was an ally to the Natives and frequently traded with the Cheyenne and Arapaho. But the construction of his fort also led to an influx of US soldiers in the area, causing some Cheyenne to move further south.

Billy Hathorn, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Billy Hathorn, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Split Up

The Cheyenne that moved south became known as the Southern Cheyenne, or Sówoníă (meaning “Southerners”). The Cheyene that remained near the Yellowstone and North Platte rivers were called the Northern Cheyenne, or O'mǐ'sǐs (meaning “Eaters”).

A New Fight

While they’d managed to find a new place to call their own, the move for the Southern Cheyenne wasn’t all peaceful. Before long, the Cheyenne and their Arapaho found themselves at war with the Comanche and their allies, the Kiowa and Plains Apache.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

A Brutal Loss

The Cheyenne fought many battles with the Comanche, but one of the worst occurred near the Washita River in 1836. There, Cheyenne warriors from the Bowstring Society clashed with warriors from the Kiowa tribe. The Kiowa won that battle, sending 48 Cheyenne warriors to their grave.

Leaflet, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Leaflet, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Lose-Lose Situation

The conflict between the Cheyenne and the Comanche led to heavy losses on both sides. With everyone losing out, the tribes decided to ally with one another in 1840. With their new alliance secure, the Cheyenne were able to expand their hunting and trading activities into the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles and northeastern New Mexico.

Regaining Ground

Around the same time, the Northern Cheyenne also made peace with old enemies. They formed an alliance with the Lakota, and in doing so, were able to regain some of their former territory around the Black Hills.

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Safety In The Mountains

The Northern Cheyenne also created settlements in the Rocky Mountains, and this move would save them from the smallpox epidemics that ravaged the plains from 1837 to 1839. Their luck ran out, however, during the 1849 cholera epidemic, which decimated half to two-thirds of the Cheyenne population.

Carolyn Miaral, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Carolyn Miaral, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Their Weapons

Like other groups of Plains Natives, the Cheyenne became very skilled at using horses in combat. Their traditional weapons included war clubs, tomahawks, lances, and bows and arrows. They also used firearms, which they got from trades or raids.

Historical Picture Archive, Getty Images

Historical Picture Archive, Getty Images

Strong Leaders

More than just fighting during times of conflict, Cheyenne warriors acted as leaders and providers within their communities. Warriors moved up in rank by achieving acts of bravery called counting coups. If they performed enough specific coups, they could earn the title of war chief.

Counting Coups

Performing a counting coup was a way of defeating an enemy, often without killing them. The coup was a way for a warrior to show his courage and involved charging at an enemy—either on foot or horseback—and getting close enough to tap them with a hand, bow or stick.

How Embarrassing

Counting coups would also involve specific challenges, like sneaking into an enemy’s camp to steal his weapons or horses. In surviving the coup, the Cheyenne warrior not only showed how brave he was, but also left his enemy with a wounded pride.

Boston Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

Boston Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

Cheyenne Military Societies

Military societies were an important part of Cheyenne culture. Society leaders were responsible for organizing hunts and raids against enemy settlement. They also kept order within communities by enforcing the laws.

Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images

Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images

Entering The Society

There are six Cheyenne military societies: Fox, Elk, Shield, Bowstring, Dog Men, and Contrary Warriors. Warriors can only join a society if they are seen as worthy enough and invited by a leader. It was common for the societies to have minor rivalries, but they would band together during times of war.

The Dog Soldiers

The Dog Men, or Dog Soldiers, are the most famous Cheyenne military society. They earned a fearsome reputation in the late 1830s, when they acted as key players in the Cheyenne’s resistance to the expansion of the United States, defending territory in present-day Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, and Wyoming.

Dori, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dori, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Fearsome Warriors

Because of their aggression and effectiveness as warriors, the Dog Soldiers were well-respected among the Cheyenne. However, that would change after one of their leaders, Porcupine Bear, was exiled. The shift in perception would also lead to major changes in Cheyenne society.

Harris & Ewing photo studio, Wikimedia Commons

Harris & Ewing photo studio, Wikimedia Commons

The Tale Of Porcupine Bear

In 1837, back when the Cheyenne and Arapaho were still fighting with the Comanche, Kiowa, and Plains Apache, a group of 48 Cheyenne Bowstring Warriors were killed while raiding Kiowa horse herds. Porcupine Bear, the chief of the Dog Soldiers, would not let the loss of so many Cheyenne warriors go unpunished.

Blood For Blood

Porcupine Bear took up the Cheyenne war pipe and carried it to all the Cheyenne and Arapaho camps, seeking support in his mission of vengeance against the Kiowa. Things were going well until he arrived at a Northern Cheyenne camp near the South Platte River.

All Fun And Games Until...

The camp had just traded goods with the American Fur Company. Liquor was among those goods, and Porcupine Bear joined the other Cheyenne in their revelry, singing Dog Soldier war songs. But a night that began with song and celebration soon turned into a living nightmare.

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

The Brawl

At some point during the night, two of Porcupine Bears cousins, Little Creek and Around, got into a drunken fight. But when Little Creek pinned Around to the floor and pulled out a knife, Porcupine Bear sprung into action.

A Tragic End

Porcupine Bear wrestled the knife away from Little Creek and stabbed him several times. Then he made Around deliver the killing blow. When it came time for justice, Porcupine Bear and Little Creek weren’t the only ones to suffer the consequences of the slaying.

John Carbutt, Wikimedia Commons

John Carbutt, Wikimedia Commons

Exiled

According to the rules of Cheyenne military societies, someone who killed a member of their own tribe had blood on their hands. The punishment for such was to be banned from joining a military society. The offender was also ousted from the community.

He Didn't Go Alone

In accordance with Cheyenne law, the Dog Soldiers expelled Porcupine Bear from their society. His family and loyal followers went with him, camping away from the rest of their community. The Cheyenne war chiefs also forbade Porcupine Bear from being a military leader in the war against the Kiowa.

Lost Glory

After Porcupine Bear’s expulsion, the Bowstring Society became the leaders of the war against the Kiowa. Despite this, Porcupine Bear led the Dog Soldiers once more in a battle against the Kiowa and their Comanche allies at Wolf Creek. Porcupine Bear and his followers were the first to strike the enemy, which was a great honor—but since they were outlaws, there was little celebration over this accomplishment.

Leonard & Martin, Wikimedia Commons

Leonard & Martin, Wikimedia Commons

They Changed Cheyenne Traditions

Before the Dog Soldiers were exiled, it was customary for men to move to their wife’s village. The exile of the Dog Soldiers introduced patrilocal customs, as their wives began the tradition of moving into a husband’s community.

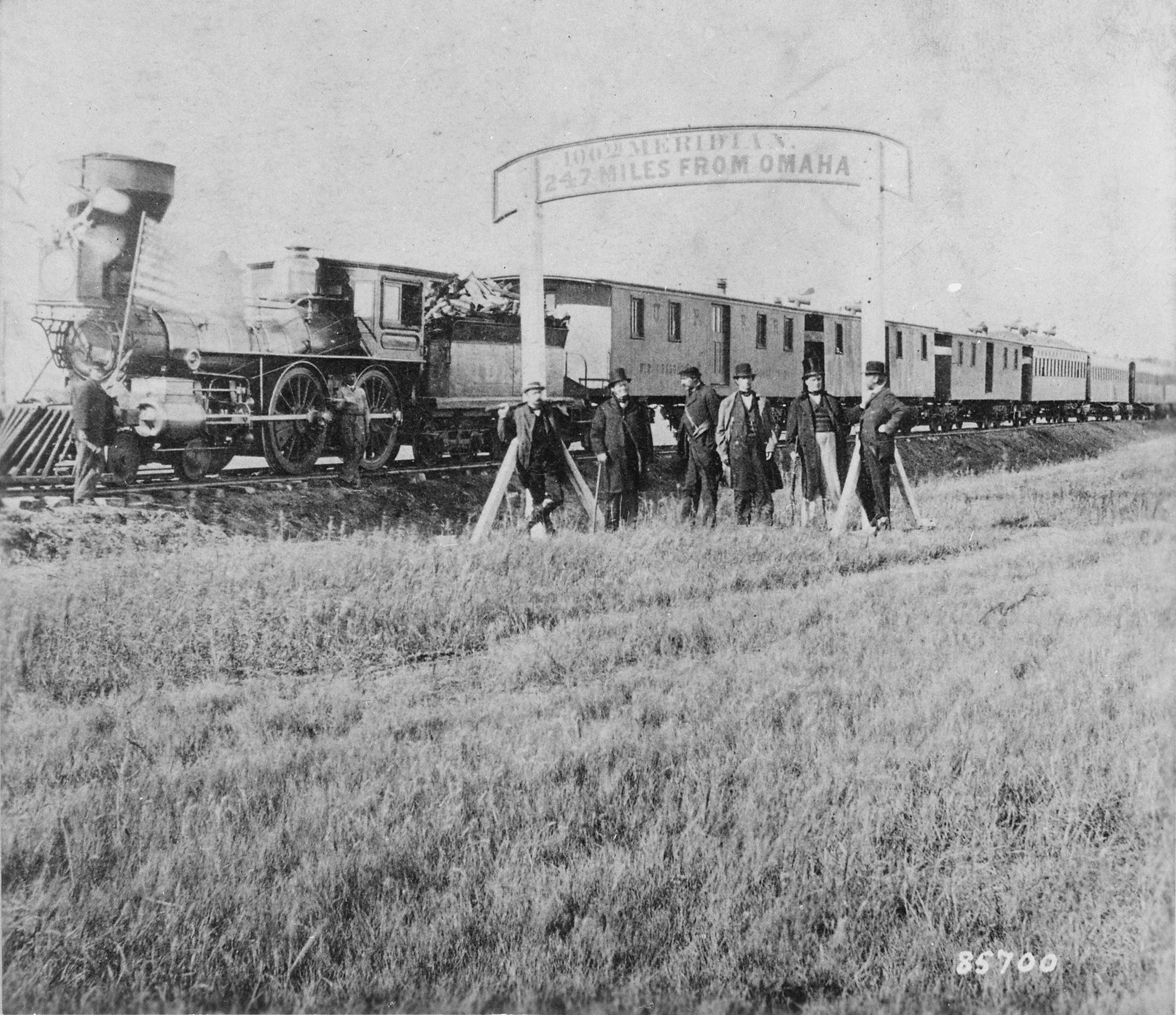

The Cheyenne vs The US Army

In 1857 the Cheyenne found themselves up against a new foe: The United States Army. While the Cheyenne had enjoyed a time of relative peace and trade with American settlers due to Treaty of 1825 and Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, tensions between the Cheyenne and the settlers were reignited after an altercation at Platte River Bridge.

National Archives, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives, Wikimedia Commons

An Eye For An Eye

During the incident, a Cheyenne warrior got wounded. He went back to his tribe, who supported his calls for retaliation. Throughout the summer of 1856, the Cheyenne carried out their vengeance on settlers along the Emigrant Trail. The US Cavalry responded in kind, killing ten Cheyenne warriors and wounding several more in at attack against a camp on Grand Island, Nebraska.

They Declared War

In 1857, the US government made their fight against the Cheyenne official. What followed was a decade of battles and raids between the Cheyenne and the US Army.

National Archives, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives, Wikimedia Commons

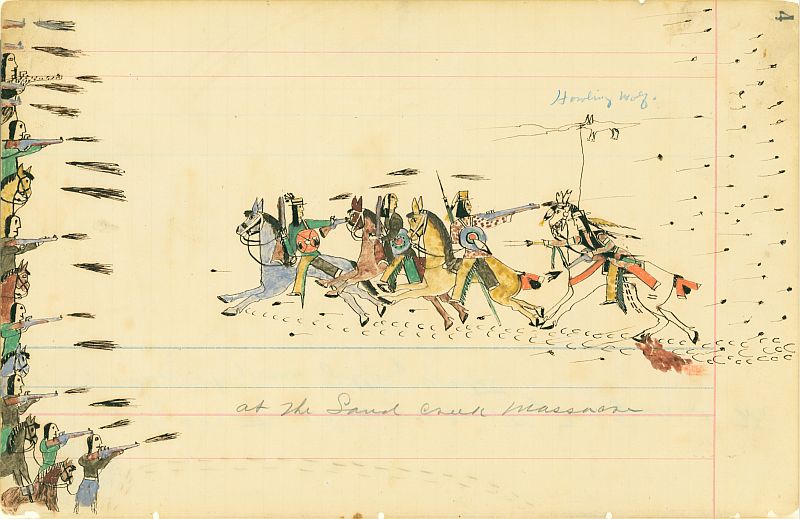

The Sand Creek Massacre

One of the most brutal events during the war was the Sand Creek Massacre. On November 29, 1864, the Colorado Militia attacked a Cheyenne camp, made up mostly women and children. Between 150 and 200 Cheyenne were slain.

Frederic Remington, Wikimedia Commons

Frederic Remington, Wikimedia Commons

They Wanted Revenge

The survivors of the Sand Creek Massacre fled to other Cheyenne camps in the northeast and told them of the attack. The Cheyenne warriors smoked the war pipe, then passed it to other camps, including their allies the Arapaho and Lakota Sioux.

Howling Wolf, Wikimedia Commons

Howling Wolf, Wikimedia Commons

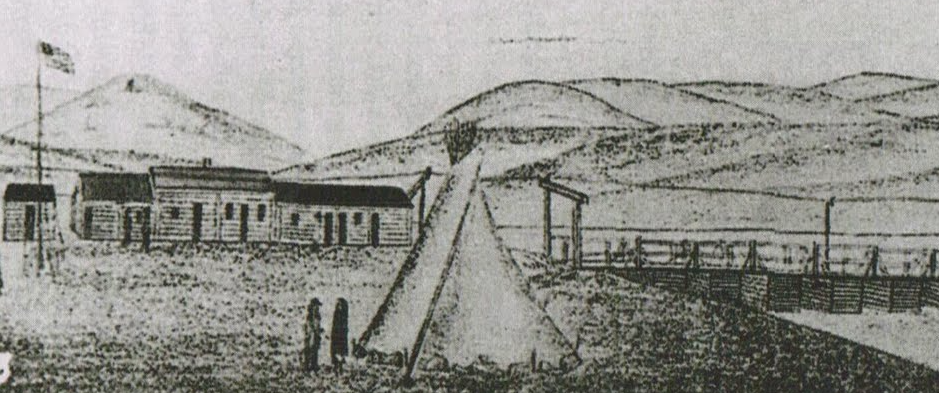

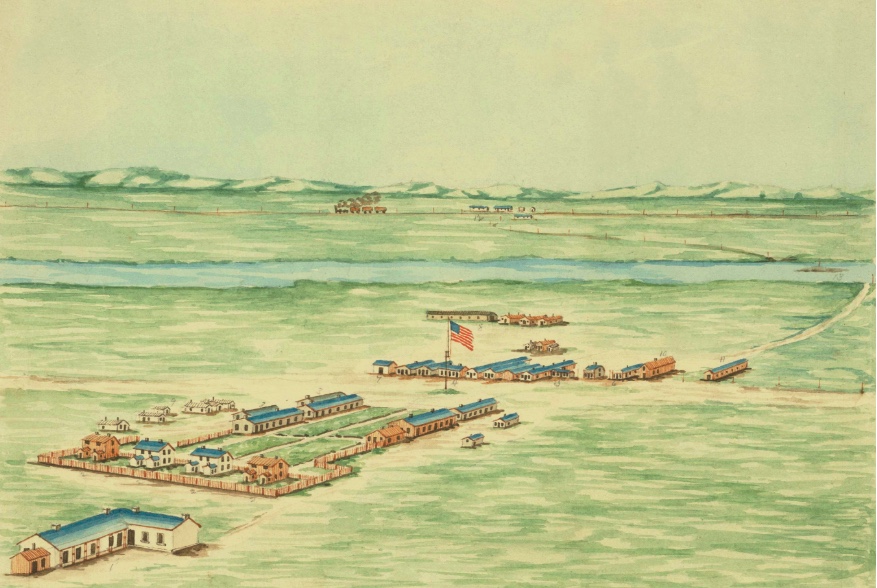

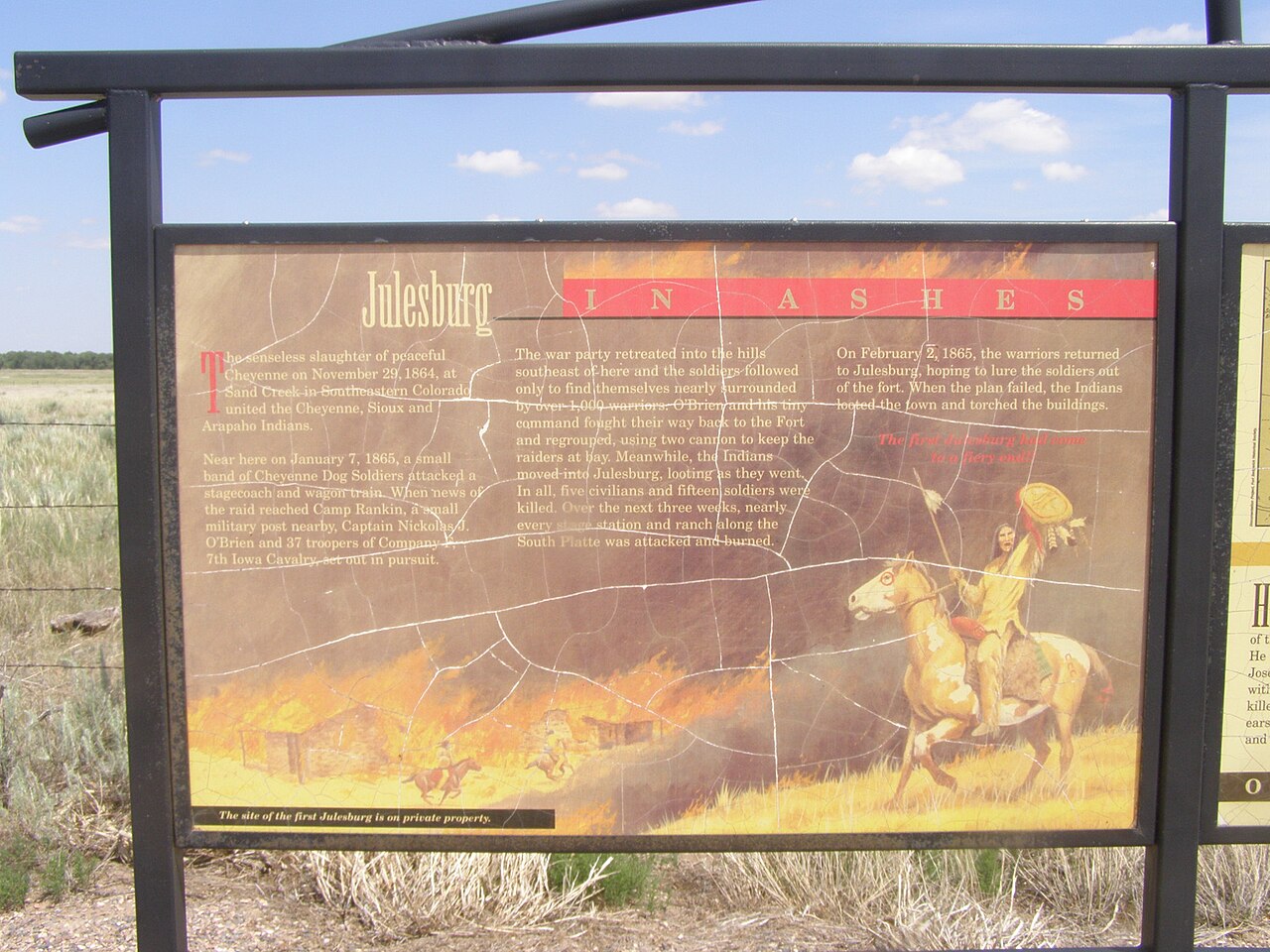

Descending On Julesburg

In January 1865, the Cheyenne got their revenge for the Sand Creek Massacre. Joined by the Arapaho and the Lakota, the Cheyenne led a force of 1000 warriors to the town of Julesburg. There, they attacked Fort Rankin (also called Fort Sedgewick).

Anton Schonborn, Wikimedia Commons

Anton Schonborn, Wikimedia Commons

Battle Of Julesburg

There were just over a hundred people defending the fort—60 soldiers and 50 armed civilians. The battle didn’t last long and ended with 14 US soldiers dead and 4 more wounded. The Cheyenne reported no casualties.

Henry Farny, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Farny, Wikimedia Commons

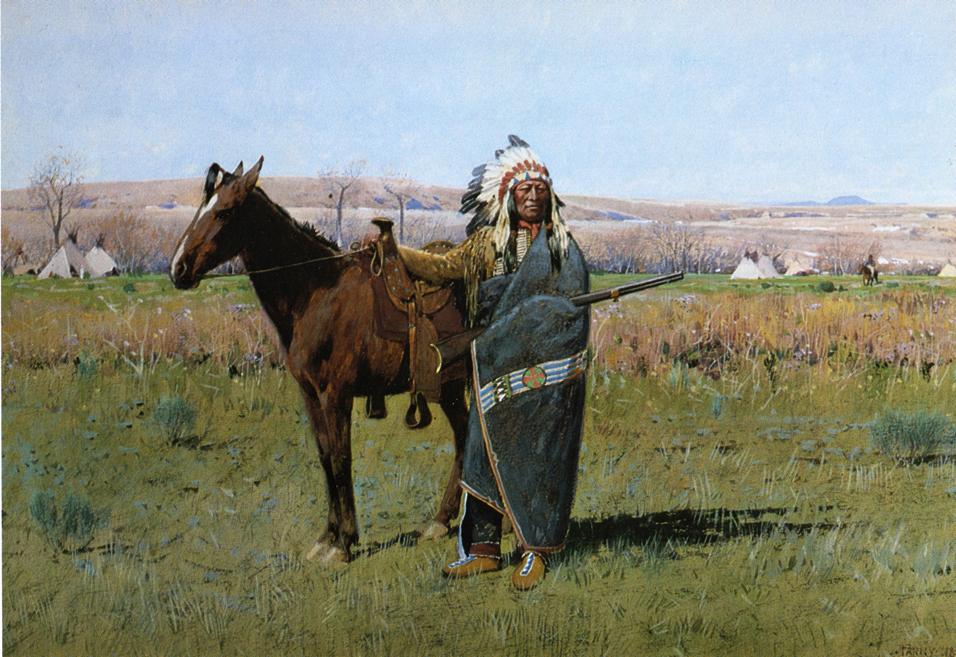

Vengeance Or Peace?

After the Battle of Julesburg, the Cheyenne went on to raid settler camps in the surrounding region. But while many of the Cheyenne supported armed confrontation with the settlers, some argued for peace. Chief Black Kettle was one of those people.

Henry Farny, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Farny, Wikimedia Commons

Black Kettle's Legacy

Black Kettle had been calling for peace for many years. In 1851, he and other Cheyenne chiefs negotiated with the US government and signed the Treaty of Fort Wise. In exchange for giving up parts of their territory, the treaty saw the creation of a reservation for the Cheyenne in southeastern Colorado.

Chris Light, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Chris Light, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Casualties Of War

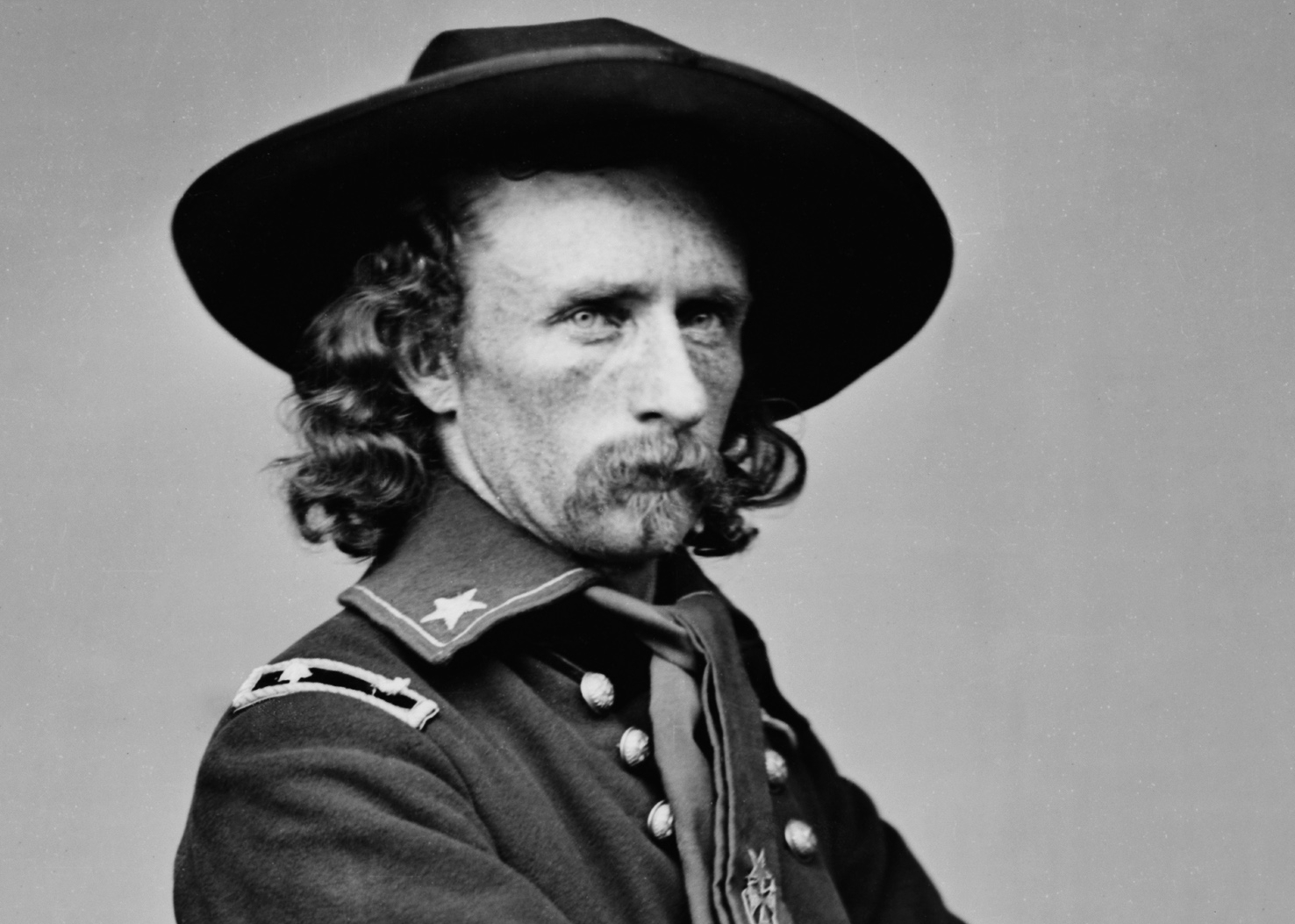

By the late 1860s, Black Kettle’s status as a peacemaker and ally to the US government was well-known—but that didn’t save him from the violence of the war. In 1868, General George Armstrong Custer led his troops in an attack against Black Kettle’s band that became known as the Battle of Washita River.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

They All Suffered

While Black Kettle had complied with government rules and kept his band on a reservation, historians believe that some of the younger members of his band had snuck out to join raiding parties against the settlers. For this, General Custer punished the whole band.

Mathew Brady, Wikimedia Commons

Mathew Brady, Wikimedia Commons

Making History

In the following years, the Cheyenne and their allies fought against the US government for control of the western plains. On June 25, 1876, the Cheyenne were instrumental in one of the most infamous battles in American history: The Battle of the Little Bighorn, also known as Custer’s Last Stand.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

He Was Outnumbered

The Northern Cheyenne, under the leadership of chiefs Two Moons and Lame White Man were joined by the Lakota Sioux and Arapaho, led by chiefs Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and Chief Gall. It’s estimated that up to 2,500 warriors met Custer’s force of 700 cavalrymen at Little Bighorn.

Edward S. Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

Edward S. Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

It Was Over Quick

Custer took command of five of his seven battalions, leaving the other two under the command of his generals. When it came down to Custer’s actual last stand, most sources say the skirmish was over in less than an hour, and at the end of it, Custer and all the men under his command lay dead.

A Short-Lived Victory

The Cheyenne only celebrated their victory over Custer for a short while. News of the battle reached Washington, D.C. just before America was about to celebrate its Centennial. Instead of fireworks that July 4th, Americans wanted revenge—and the US Army obliged by increasing their efforts to capture the Northern Cheyenne.

Destruction Everywhere

The US Army destroyed many Northern Cheyenne lodges, taking their horses and supplies. While many Cheyenne resisted for a time, the late 1870s saw several great chiefs like Morning Star (also called Dull Knife) and Two Moons surrender their forts.

William Henry Jackson, Wikimedia Commons

William Henry Jackson, Wikimedia Commons

It Didn't Go As Planned

When the Cheyenne surrendered, they’d hoped to stay in the north with their Sioux allies. The Army had other plans, and pressured the chiefs to settle on moving south, to reservations. Many Cheyenne live on the reservations to this day, at the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana and the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes reservation in Oklahoma.

Library of Congres, Wikimedia Commons

Library of Congres, Wikimedia Commons

Final Thoughts

From their origins on the Great Plains to their present-day efforts in preserving their language and customs, the Cheyenne's ability to adapt has helped them thrive amidst all of the challenges history has thrown at them. Travelers who want to learn more about the tribe are welcome to visit the reservations. Along with tours and a chance to get authentic Cheyenne goods and treats, you might get a chance to take part in a unique celebration like a Pow-Wow.