People Of The South Wind

Kaw Nation is a federally recognized Native American tribe currently living mostly in Oklahoma. They've relocated a few times, and not always willingly. But forced relocation hasn’t been their only challenge. The Kaw tribe has been around for centuries, and has endured more tragedy than you could imagine. With one devastating event after another, the tribe nearly became extinct—and had to take drastic measures to rebuild their numbers.

Sadly, their story doesn’t exactly have a happy ending, either.

A State Was Named After Them

The Kaw people, also known as Kanza or Kansa, used to live along the Kansas and Saline rivers in what is now Kansas. As a result, both the state of Kansas and the Kansas River are named after the tribe.

As well, the capital of Kansas, Topeka, is said to be the Kaw word Tó Ppí Kˀé, which means “a good place to grow potatoes”.

But even though Kansas was named after them—it’s not where they primarily reside today.

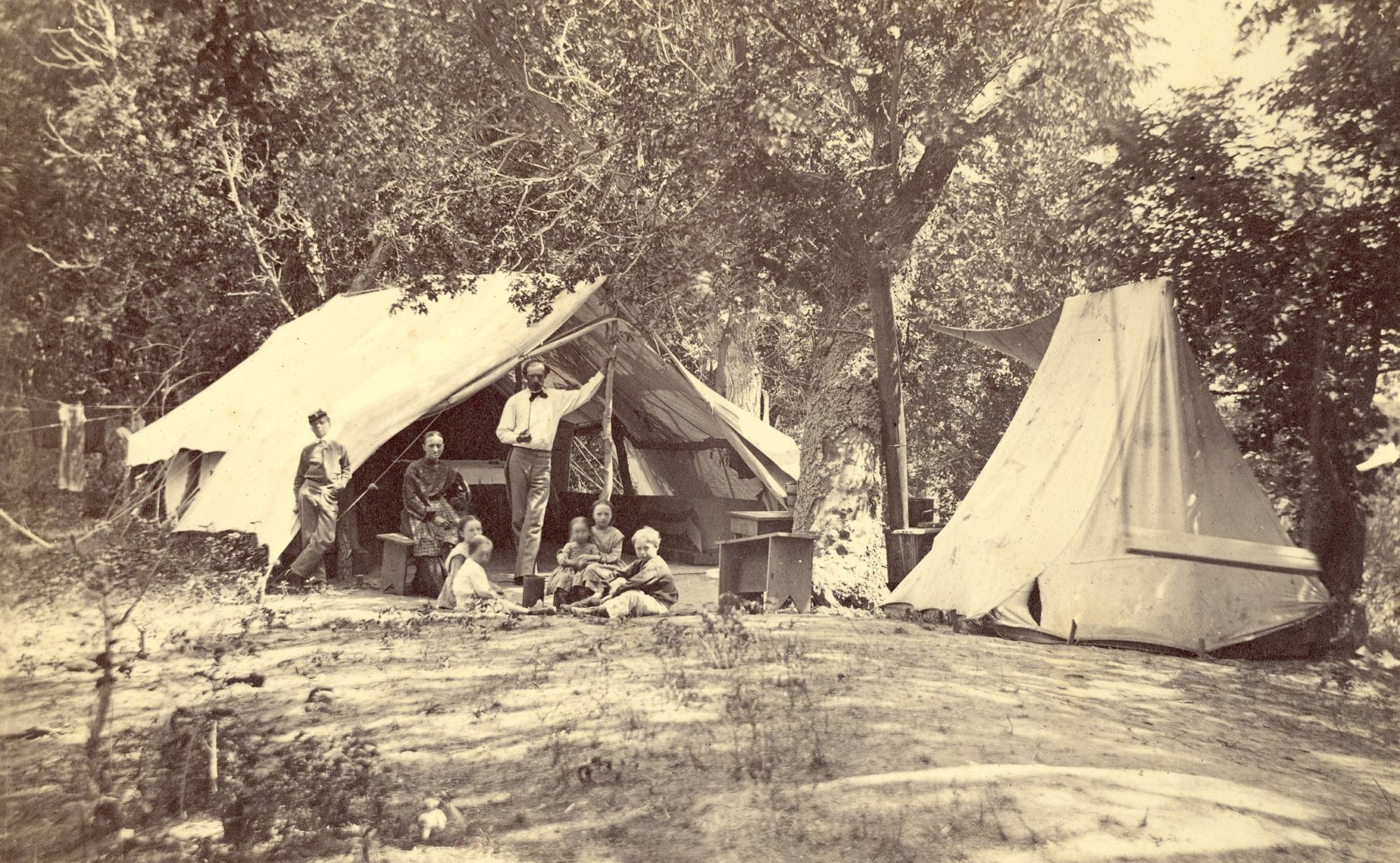

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Where They Live Today

Today, while some still live in Kansas, many Kaw people live in other states, like Texas, Missouri, and even parts of Canada and the UK, and their headquarters is actually now in Oklahoma. But their relocations over the years have been anything but easy—and the reasons are utterly devastating.

John H. Fitzgibbon, Wikimedia Commons

John H. Fitzgibbon, Wikimedia Commons

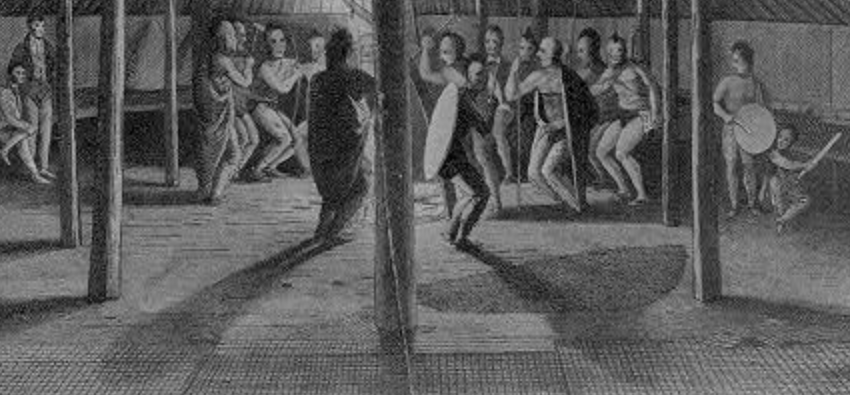

They Were Semi-Nomadic

Like many other Native American tribes, the Kaw lived a traditional semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle for centuries. They easily lived—and thrived—off the land, grouping with other tribes for trade.

Samuel Seymour, Wikimedia Commons

Samuel Seymour, Wikimedia Commons

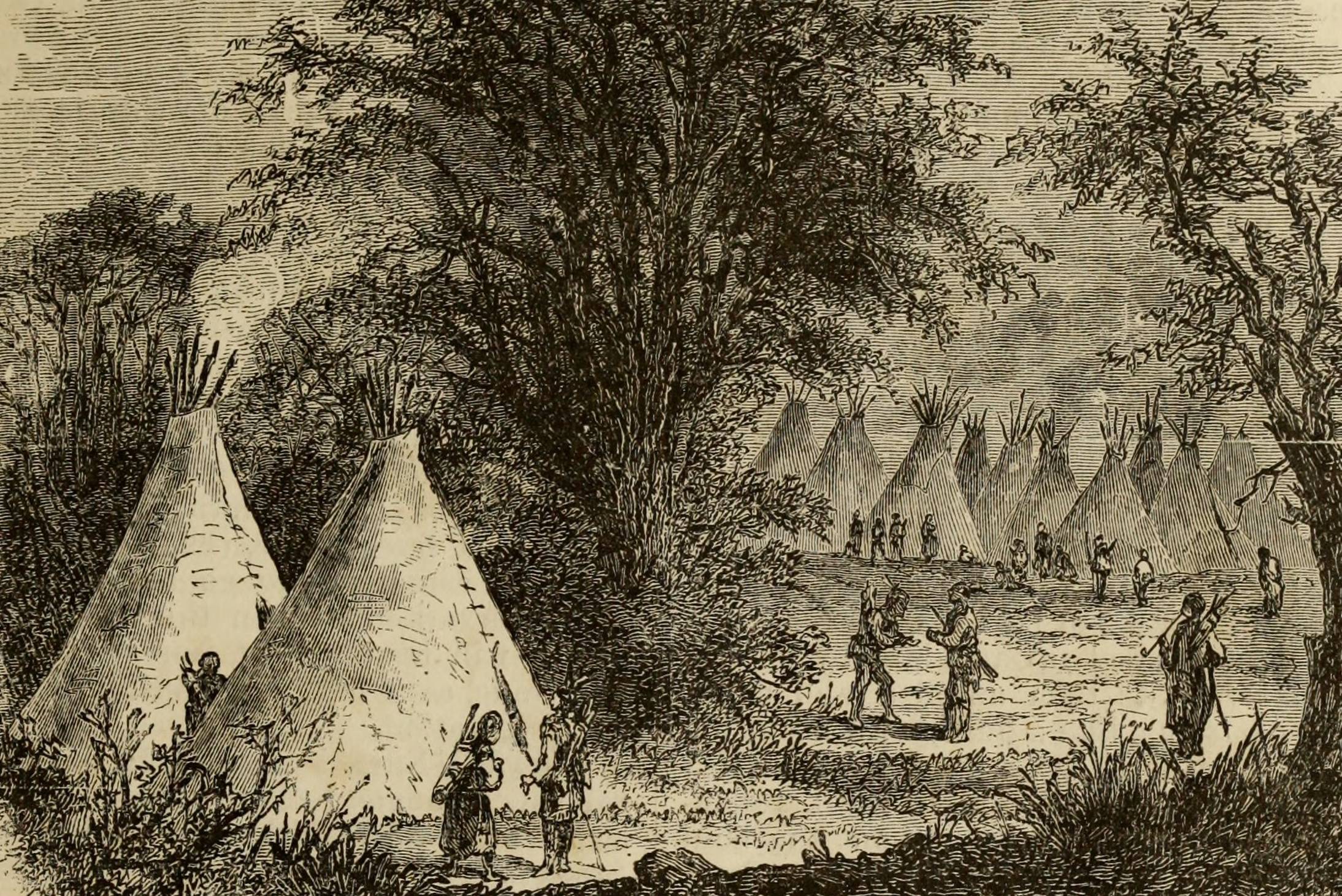

The Lived In Earth Lodges

Their villages were made up of several large dome-shaped houses called “earth lodges”. They were made using wood pole frames with soil and sod packed on top that would harden to create the enclosure.

They also had smaller dwellings known as “cabanas”, which were covered in bark, and even smaller, portable dwellings called “tipis” that were covered in animal hide and used for hunters and warriors who were on the move.

John W. Barber and Henry Howe, Wikimedia Commons

John W. Barber and Henry Howe, Wikimedia Commons

They Were Skilled Providers

The Kaw have always been excellent providers. Their traditional subsistence practices largely included hunting, trapping, gathering, and even farming.

Kaw women were expert gatherers who regularly collected a number of nuts, berries, and roots from their environment.

And as skilled hunters, the Kaw men didn’t just pursue small game, they also hunted for bison, deer, and elk.

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

They Farmed, Too

While many tribes were either hunter-gatherers or farmers, the Kaw were actually both. Along with small and large game, berries, and roots, they also cultivated crops like corn, beans, and squash.

In order to make this work, only some Kaw were nomadic—usually the men, who left the village for hunting trips.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

They Had Various Hunting Methods

When Kaw men left for hunting trips they brought along a series of important tools—all of which they made by hand themselves. Traps and snares were used for capturing smaller game, and spears and arrows were used for a variety of other animals.

They also used extensive tracking techniques and fake animal calls to attract their prey closer.

But hunting wasn’t their most important job.

Missouri Historical Society, Wikimedia Commons

Missouri Historical Society, Wikimedia Commons

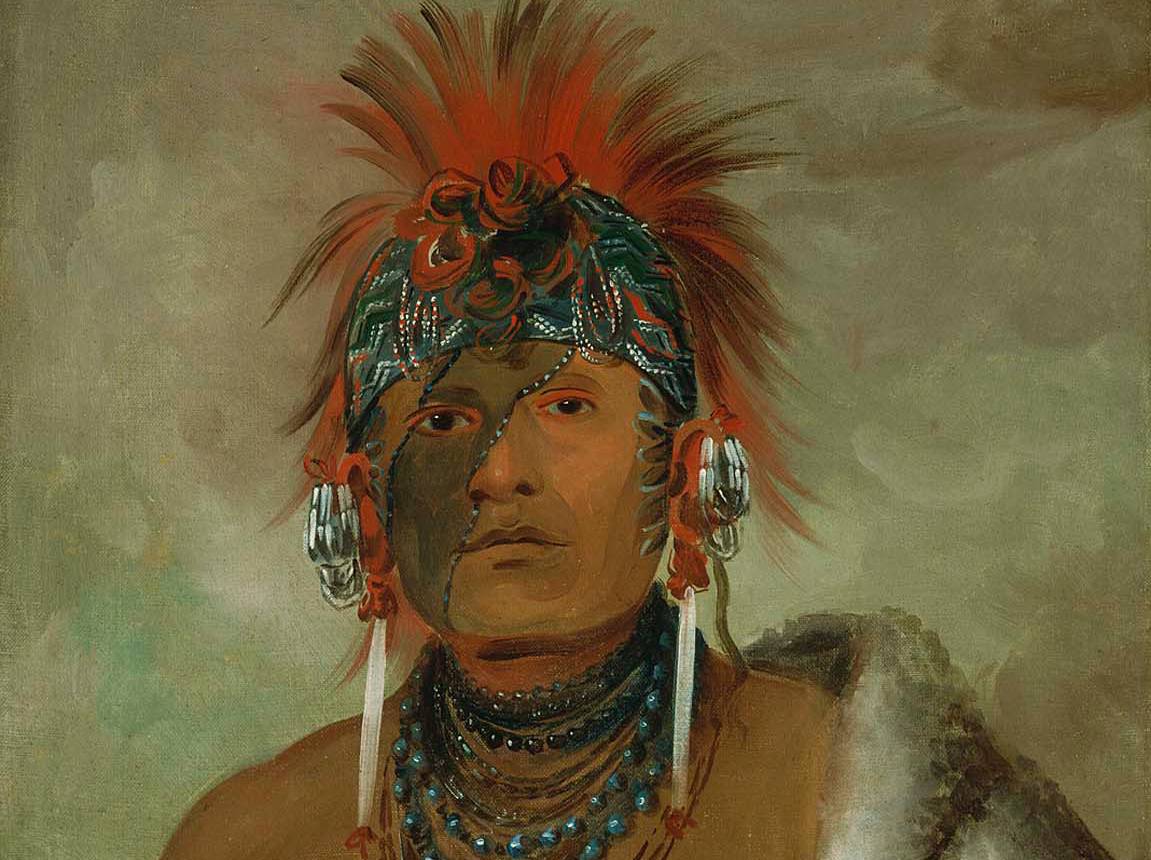

They Were A Warrior Tribe

Kaw men were basically professional warriors who almost continuously engaged in raids and counter-raids. Because of this warrior lifestyle, boys and young men were trained to protect their tribe from a very early age.

In fact, this warrior culture used incentives to keep their warriors strong.

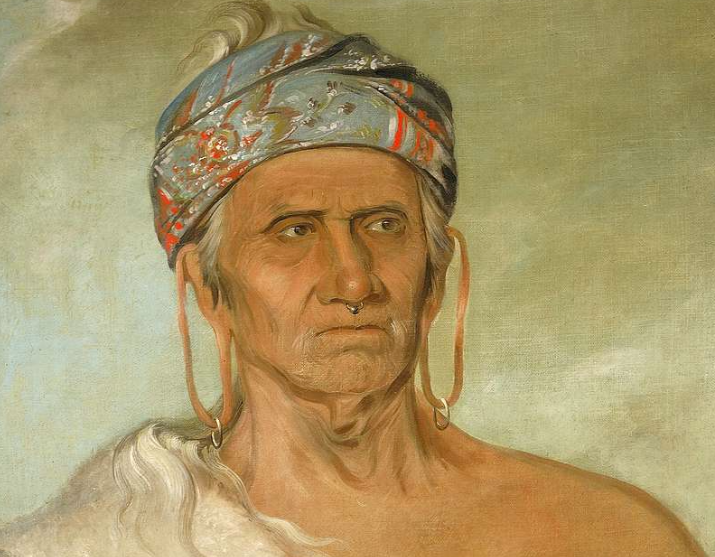

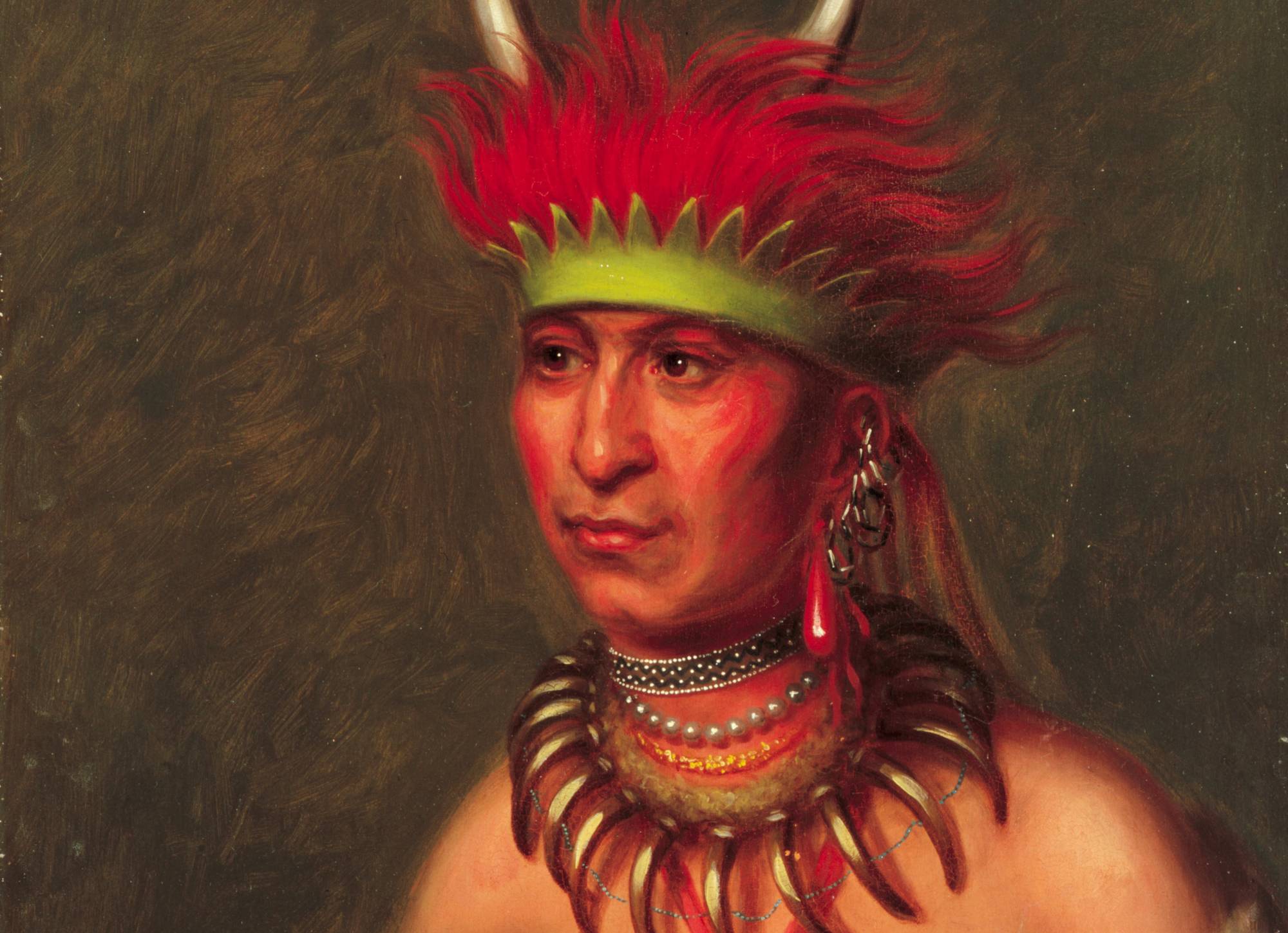

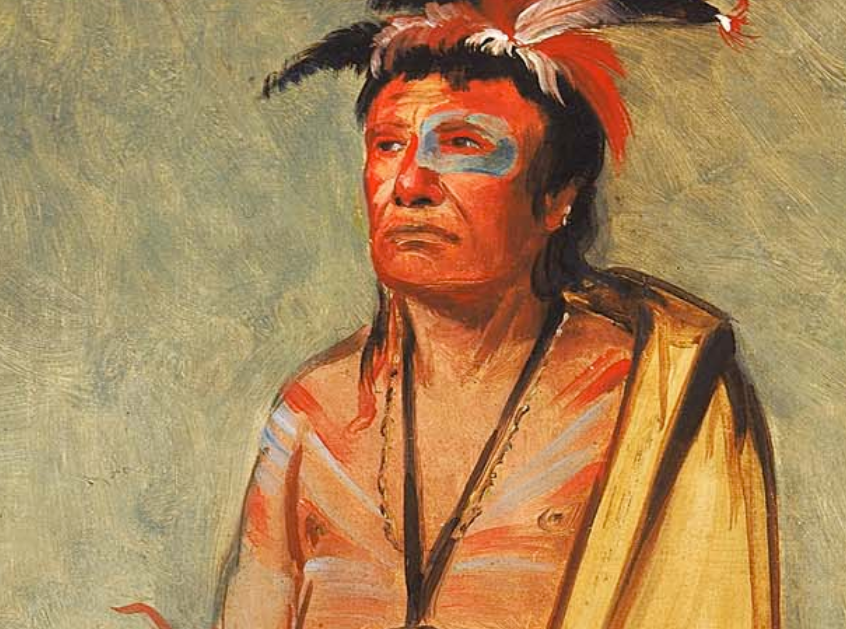

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

They Had Incentives

As an incentive, male Kaw would earn honors by demonstrating bravery and valor in battle—especially when raiding other tribes. Killing enemies and capturing horses and other goods were two ways a Kaw warrior would prove willingness to risk their life—thus, earning them a reward when they returned.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

They Earned A Reputation

Kaw warriors who were successful in battle would earn stature within the tribe, especially when they gave up their loot to the chiefs upon their return. These warriors were seen as top-notch men, and the Kaw women all wanted one of those. But what earned them the highest prestige was when they battled against a certain enemy tribe.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

Beware Of The Pawnee

The Kaw had many conflicts with other Native tribes, but their biggest enemy was the Pawnee. They lived in the same area, which means they were constantly in competition for resources. Their rocky relationship was marked by conflicts and raids, and overall, they became known for their “intense hostility”.

In fact, this constant hostility is one of the reasons the Kaw eventually had to relocate.

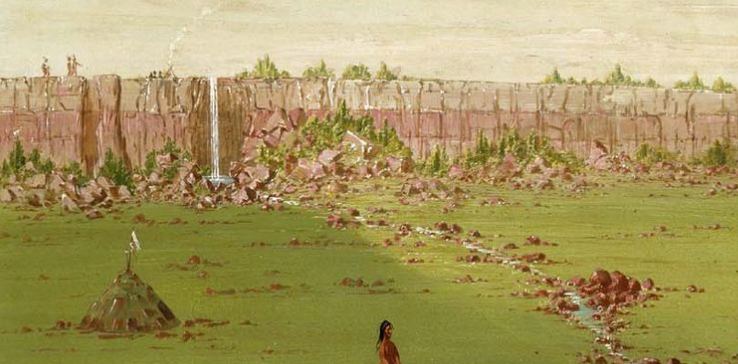

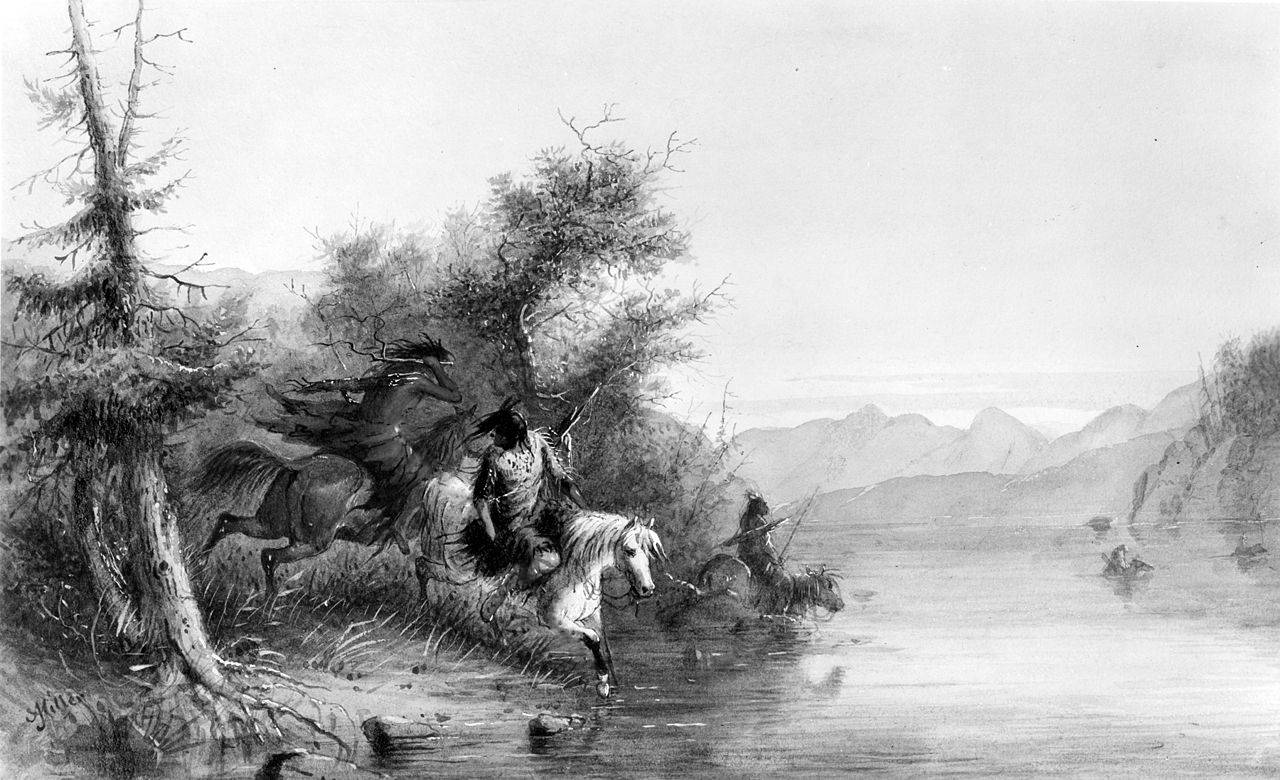

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

Their Ancestral Home Was In Ohio

If we go back to the very beginning, or at least as far as historical records will take us, the Kaw are actually a member of the Dhegiha branch of the Siouan language family. This group of about five tribes was located way out in Ohio.

In 1300 AD, due to tribal conflict, they began migrating westward down the Ohio River, eventually settling in present-day northeastern Kansas and northwestern Missouri.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

They Tried To Hide From Other Tribes

After settling into a new home along the Kansas River, the Kaw camped and hunted there for at least a century. They chose their location primarily for the bison herds, and the fact that it was farther from trading posts which attracted other tribes.

However, this is when they ended up closer to the Pawnee tribe—and then an even bigger threat emerged.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Settlers Arrived

European settlers were already present in the area by the early 1700s, and had already discovered the Kaw tribe when French explorers discovered one of their earlier villages in 1724. But things weren’t hostile just yet. In fact, for many years they were able to peacefully trade with the French.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Village Of Kanzas

Later, in 1804, famous explorers Lewis and Clark came across that same village. The Kaw had no longer lived there and it was now in ruins, and so they referred to it as “the old village of the Kanzas”—which may have played a part in naming the state later on.

Eventually, any peace and trust with the settlers was squashed—and this is when the real trouble began.

Edgar Samuel Paxson, Wikimedia Commons

Edgar Samuel Paxson, Wikimedia Commons

Their Population Was In Trouble

During the 1700s, the Kaw population was approximately 1,500—and they managed to keep it that way for quite some time. But once the Europeans began lurking around more often, their traditional lifestyle took a dangerous turn.

Everyone Was Moving In

In 1803, the US purchased Louisiana Territory and began moving settlers in. Not only that, Eastern Indians were also being forced to migrate into the region.

Settlers were in search of “rich and exuberant soils”—which happened to be on Kaw lands. Not only did this create boundary issues, but it also created further tensions between neighboring tribes, too.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

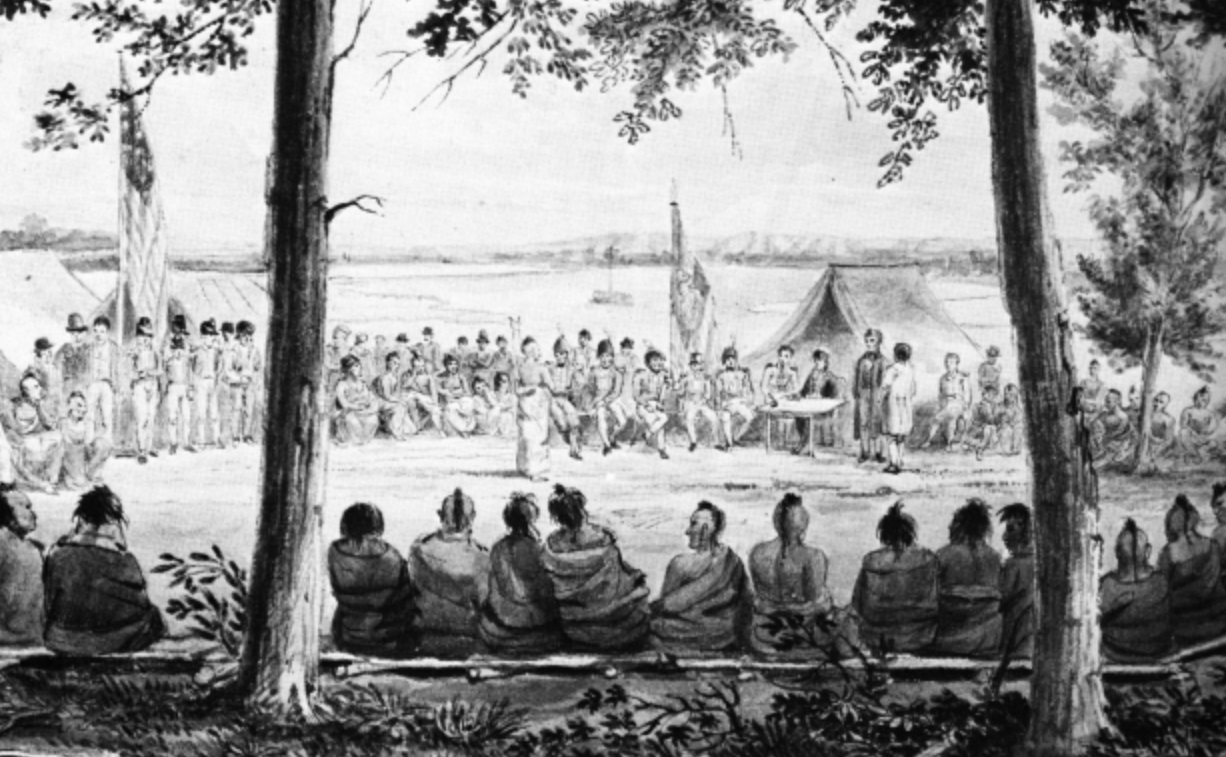

They Made A Promise

By 1825, the Kaw had no choice but to make an agreement with the US. They gave up a large portion of their land to the Americans, in exchange for a promise of an annuity of $3,500 (to be paid in goods and services) annually for 20 years.

However, the Americans didn’t follow through on their promise.

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

They Lost Trust

The annuity was often late, or ended up in the pockets of corrupt government officials and merchants. And, of course, the land they had left continued to be invaded by settlers, and other tribes who were also losing land.

As more and more people encroached on their lands, the Kaw found themselves with increasing threats—and one in particular nearly decimated the entire tribe.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Picryl

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Picryl

The Had No Immunity

Beginning in 1827 and lasting well into the 1830s, the Kaw faced a devastating smallpox epidemic, killing at least 500 people of their tribe. In total, about 17,000 Native Americans lost their lives.

Apparently, the epidemic was linked to a steamboat that carried infected individuals upriver from St Louis.

At the same time, the Kaw tribe was facing another significant challenge.

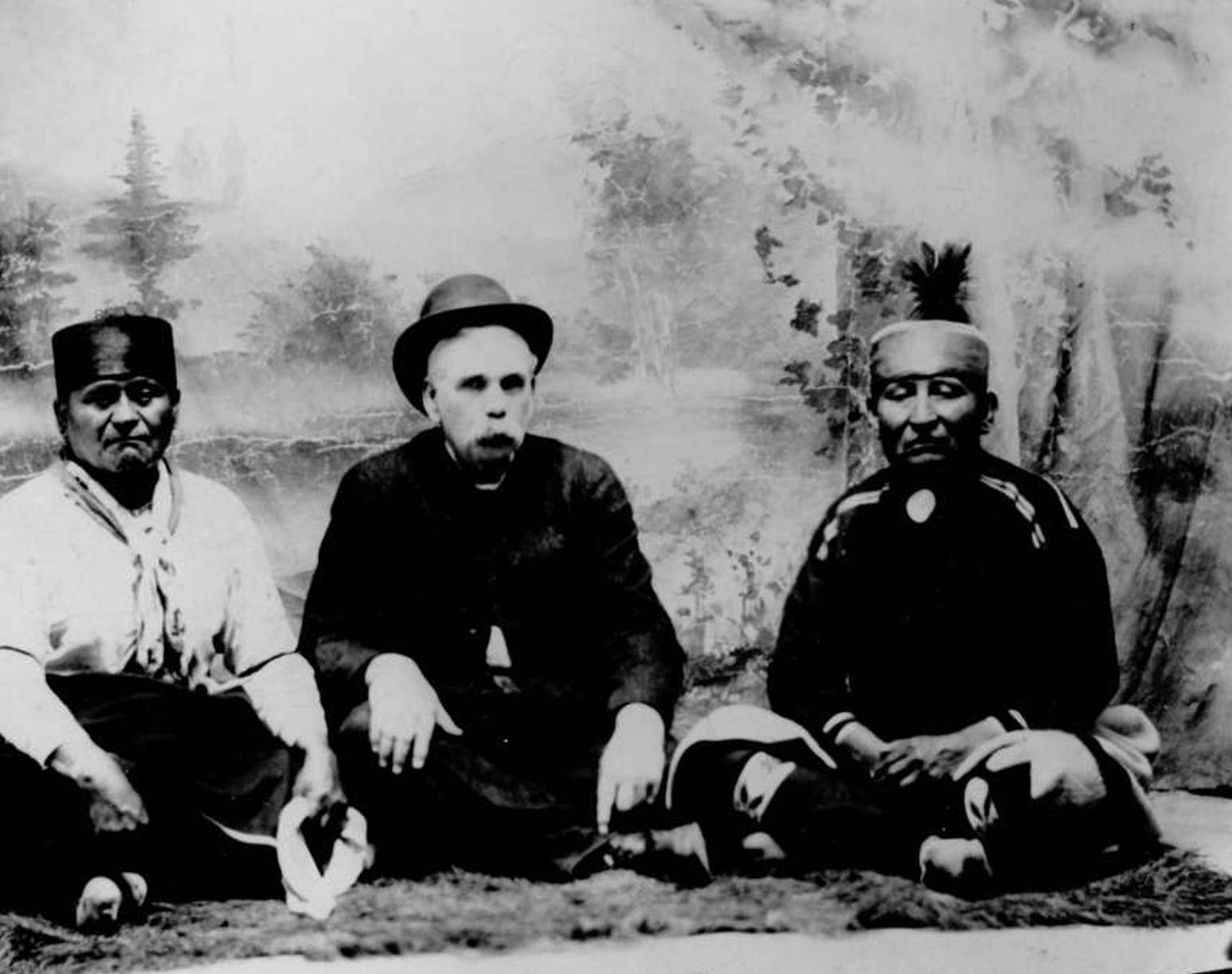

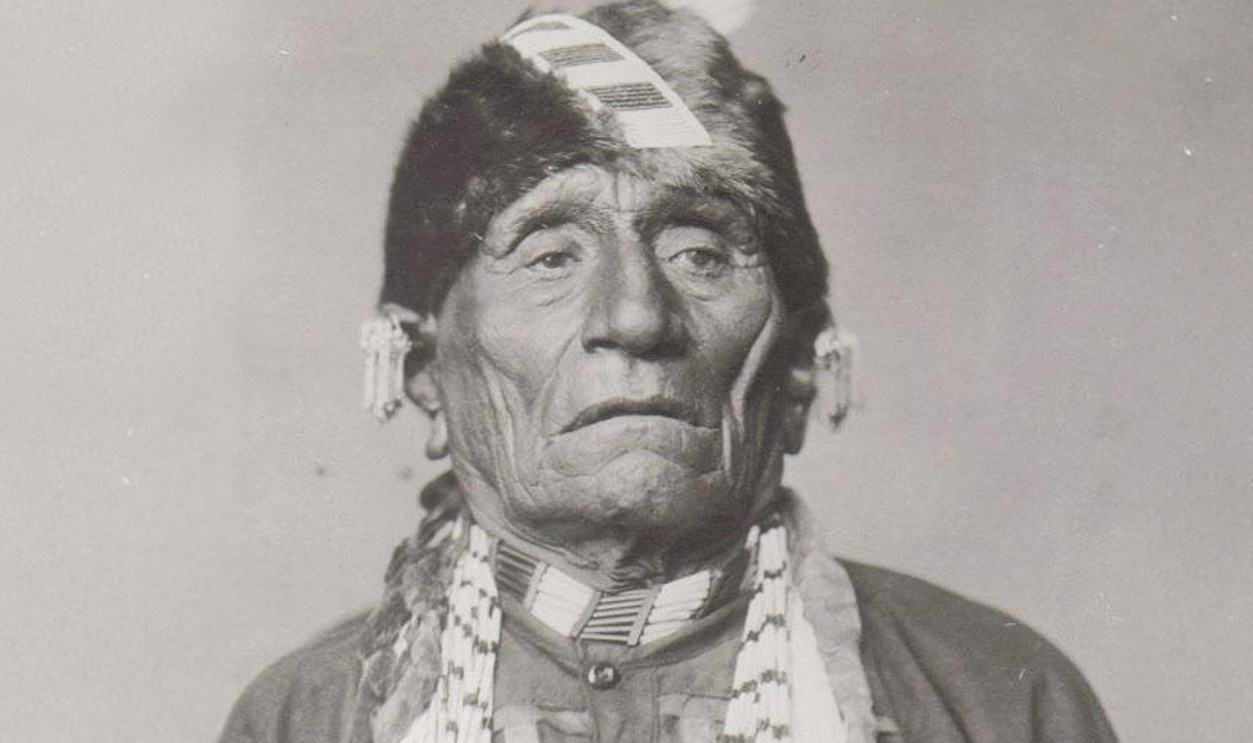

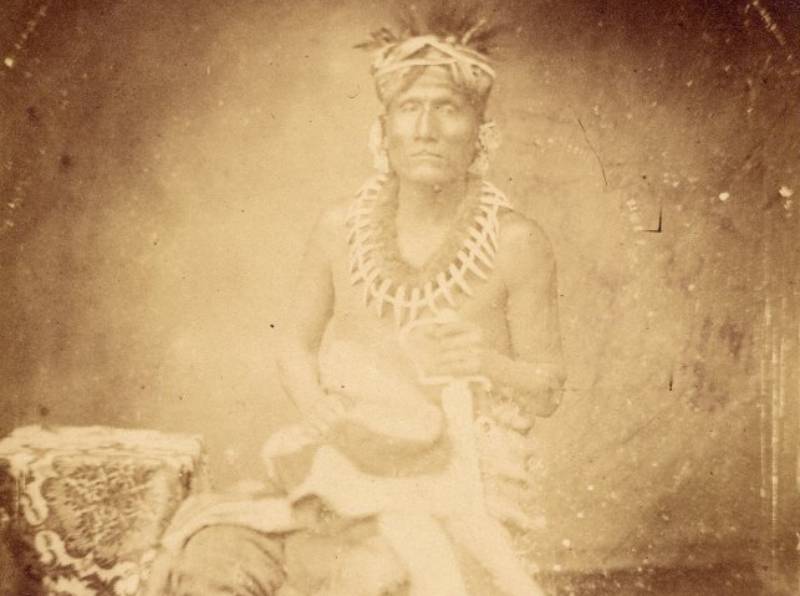

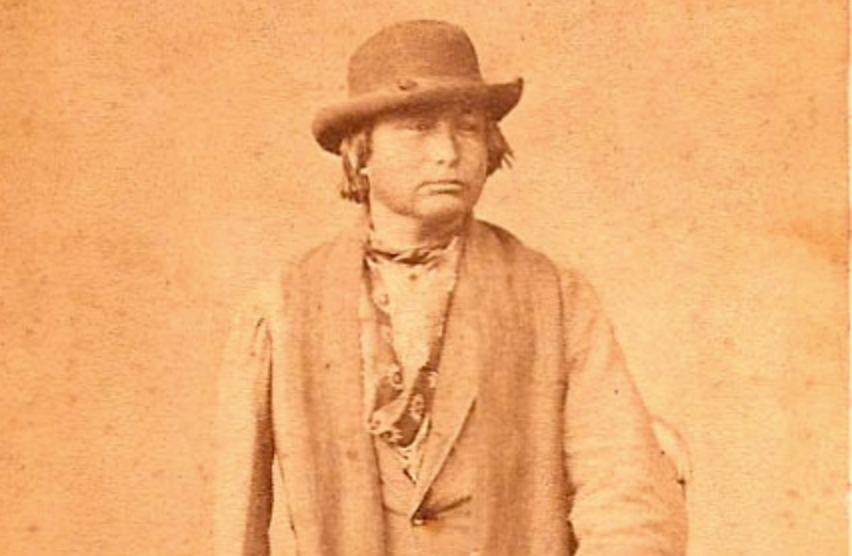

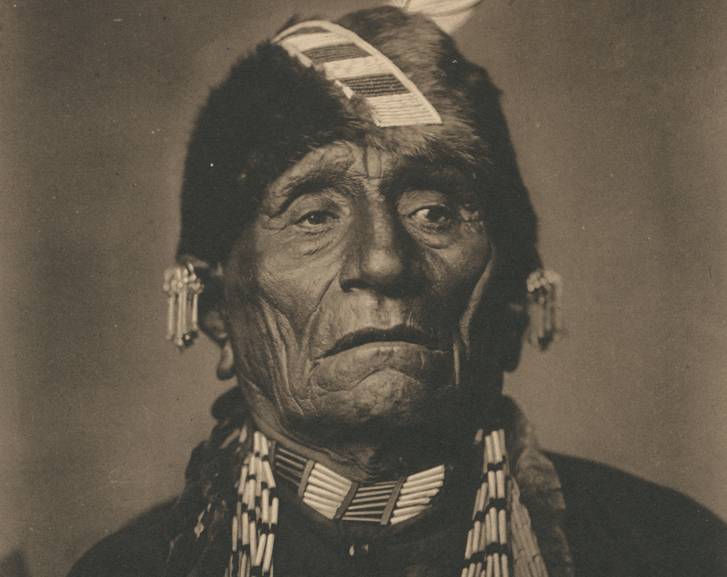

John H. Fitzgibbon, Wikimedia Commons

John H. Fitzgibbon, Wikimedia Commons

They Split Up

During this period of particular struggle, the Kaw tribe split into four different groups—who then competed with each other. They lived in separate villages and adopted different lifestyles.

Three of the groups favored retaining their traditional ways—while one group wanted to give up their land and culture to accommodate the United States.

John H. Fitzgibbon, Wikimedia Commons

John H. Fitzgibbon, Wikimedia Commons

The Odd One Out

The one group who wanted to ally with the US was led by Chief White Plume. This group included 23 tribespeople of “mixed blood”—the sons and daughters of French traders who had taken Kaw wives.

This band of Kaw people became known as “Half-breed” —a name they gave to themselves. The other bands adopted the names Koholo, Picayune, and Rock Creek.

As troubling as this way, it was nothing compared to what came next.

National Museum of Denmark, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

National Museum of Denmark, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Great Flood Of 1844

In 1844, things took a turn for the worst for the Kaw when a disastrous flood destroyed most of their land—leaving them in a very bad situation. The flood had completely ruined their farmlands, and took out their villages, making it nearly impossible for them to survive with even basic necessities.

But the Kaw weren’t the only people affected.

Unknown Author, CC BY-SA 2.5, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, CC BY-SA 2.5, Wikimedia Commons

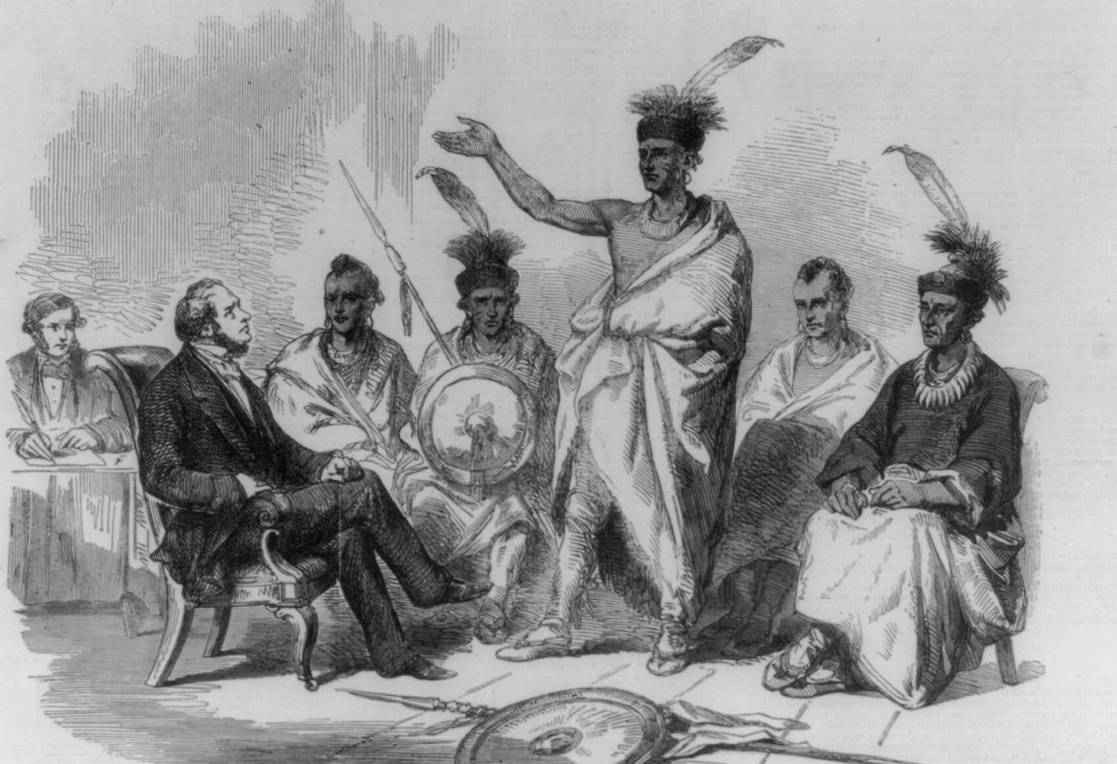

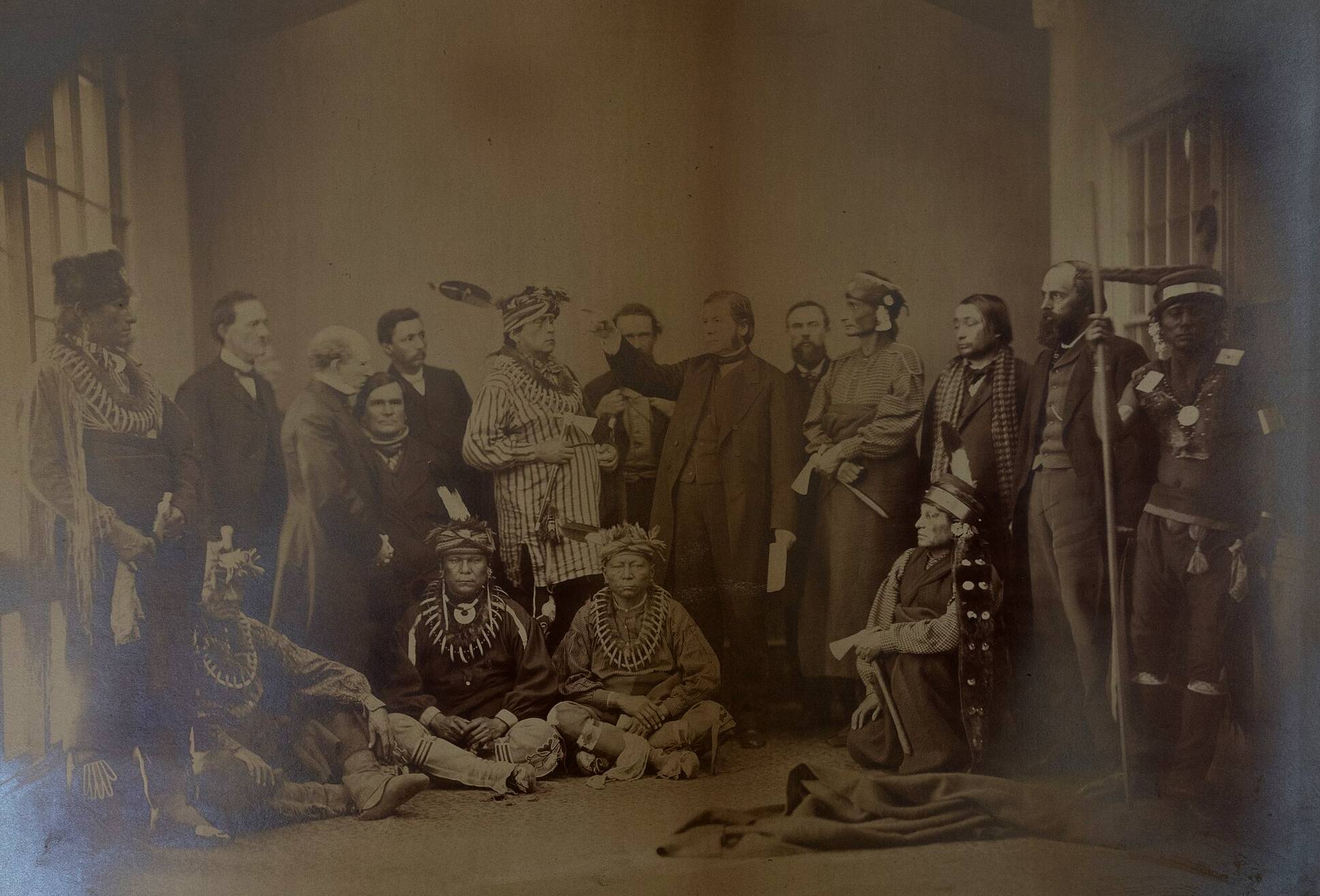

They Were Forced Into Another Agreement

Native tribes aside, the massive flood also affected the settlers—which gave them even more need for land. Within two years, the Kaw were nearly dying once again, and had nowhere to build their lives back.

This led to another inevitable agreement with the Americans.

Missouri Historical Society, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Missouri Historical Society, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Their New Lands Weren’t As Promised

In 1846, the Kaw sold most of their remaining 2 million acres of land for $202,000 plus a 256,000-acre reservation on Council Grove, Kansas. While the area was actually a beautiful land filled with lush forest, fresh water, and tall grass prairie—the Americans failed to mention one very dangerous detail.

University of Cincinnati Libraries Digital Collections, Picryl

University of Cincinnati Libraries Digital Collections, Picryl

They Had Dangerous Trespassers

Their new reservation sat upon land that happened to be a favorite stopping place for “rough-hewn teamsters”, which were basically not-so-nice people who often used the land for transportation purposes. In addition to these guys, the Kaw’s new land was also frequented by traders and merchants who often felt entitled.

As you can imagine, the Kaw and their unfriendly guests did not mesh well.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

They Were Dying, Again

The first few groups of Kaw to arrive on the new reservation ended up severely harmed by various groups of Europeans who aggressively traversed their reservation. Not only that, disease and starvation continued to threaten Kaw survival.

A flourishing whiskey trade was next, which happened to take place in Council Grove as well, making things even harder for the Kaw. Eventually, the government stepped in—but not in favor of the Kaw.

The Settlers Got Their Way

In 1860, White settlers were continuing to invade Indian lands and efforts by soldiers to keep them off didn’t actually help. So, instead, the government went ahead and reduced the Kaw reservation to a mere 80,000 acres. Obviously, that didn’t help the problem.

But the government didn’t care about the Kaw—at least not yet.

William S. Soule, Wikimedia Commons

William S. Soule, Wikimedia Commons

They Lost Even More Men

The following year, the Kaw suddenly became an asset to the American government when the American Civil War broke out. Native Americans were being recruited as soldiers and scouts to avert invasions by other slave-holding tribes and Confederate supporters in Indian Territory.

With an already weak population, the government managed to force 70 Kaw men to join the fight—and only 49 of them came home.

And if you think life got easier for them after the war—think again.

They Were Used

Even though the Kaw were said to be “assets” in the war, they were actually just disposable pawns. And not long after the war ended, European-Americans pressed for an official removal of all Indians, including the Kaw.

At the same time, one of the Kaw’s tribal enemies came looking for revenge.

A Battle For Revenge

The Kaw and Cheyenne had been enemies for a long time. A battle, which had taken place a year prior, ended with a much bigger loss for the Cheyenne than the Kaw, and they promised a rematch.

On June 1, 1868, the Cheyenne came knocking—about 100 of them, to be exact. They were so intimidating that White settlers ran off scared, hiding in Council Grove. But the Kaw, who were literally bred for battle, happily geared up.

Indian Charley

As the battle began, a mixed-blood Kaw interpreter and grandson of Chief White Plume, named Joe Jim, rode 60 miles on horseback to Topeka to request assistance from the Governor.

Riding along with him was a young boy, only eight years old, named Charles Curtis, or “Indian Charley”. Curtis would later become a jockey, a lawyer, a politician, and Vice President of the United States under Herbert Hoover—as well as a troublemaker for the Kaw specifically.

And while the battle was obnoxious in every way possible—it was over long before these men could even reach help.

Craig Wright Farnsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Craig Wright Farnsworth, Wikimedia Commons

They Laid Curses On Each Other

The Cheyenne outnumbered the Kaw, but that didn’t matter. The two tribes put up quite a stink, with serious horsemanship, fearsome howls, and terrifying curses laid upon their enemies. Bullets and arrows flew through the air almost constantly.

But after four hours, everything was over. And believe it or not, nobody was hurt on either side.

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

It Was Short—And Sweet

The worst thing to happen during the battle was a few stolen horses. It ended very simply—with a peace offering of coffee and sugar by the Council Grove merchants. The Cheyenne were first to accept, and the Kaw basically laid down their arrows and said, “sure, why not”. And they all enjoyed a cup of hot joe.

As interesting as this battle was, it had nothing to do with stopping the government from kicking them off their land.

George W. Scott, Wikimedia Commons

George W. Scott, Wikimedia Commons

They Had To Go

By June of 1873, White pressure finally forced the Kaw out of Kansas. The government had now set up another reservation for them in Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma). Within two weeks, 533 men, women, and children packed up their few belongings and left for the junction of the Arkansas River and Beaver Creek in what would become Kay County, Oklahoma.

That winter, they experienced one centuries-old tradition for the very last time.

University of Washington, Wikimedia Commons

University of Washington, Wikimedia Commons

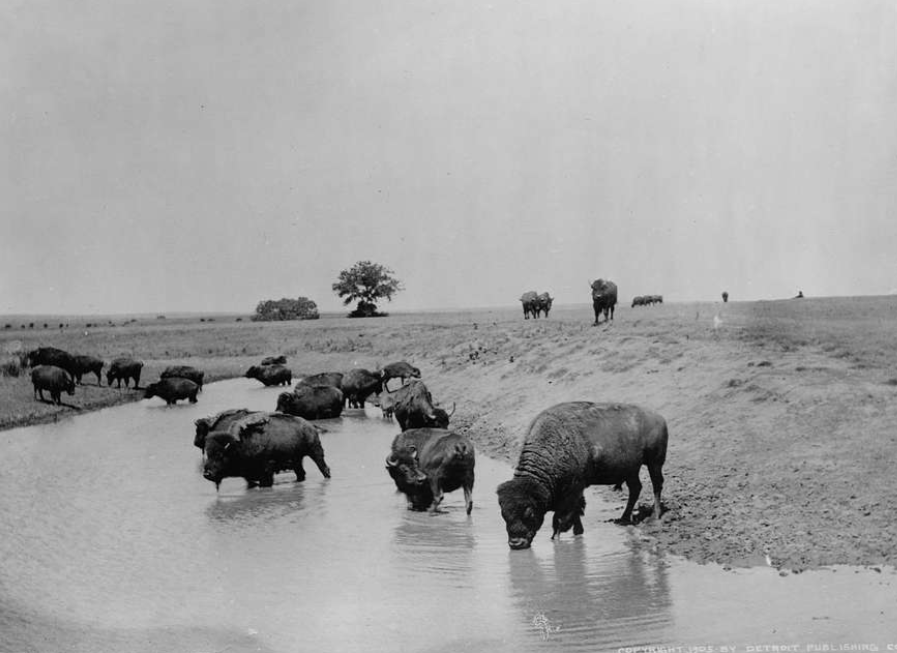

The End Of An Era

After they were forced to leave their lands again, the Kaw made their last successful buffalo hunt, journeying on horseback to the Great Salt Plains. They then preserved the buffalo meat and sold the buffalo robes for $5,000.

But once they got to their new location—life wasn’t any better.

Their Culture Was Lost

Once the Kaw got to Oklahoma, their tribe continued to decline. By 1878, nearly half of their population died from disease. They lost a significant amount of their traditional lifestyle and were now forced to make an income in other ways—primarily by leasing their land to White ranchers, of course.

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

They Established A Government

In 1884, the Kaw needed someone to handle the land leases better, and that’s when they began electing a government with a Chief Councilor and a representative from each of the four bands, the Picayune, Koholo, Rock Creek, and Half-breed.

A man named Washungah was elected as the Chief Councilor in 1885 and the tribal headquarters was later named Washunga to honor him.

This new government helped secure the tribe from White harassment—but they still weren’t out of the woods yet.

Smithsonian Institution, Wikimedia Commons

Smithsonian Institution, Wikimedia Commons

Officially On The Brink Of Extinction

The Kaw tribe continued to decline, especially the full-bloods. By 1888, the tribe numbered only 188 persons—they were now on the brink of extinction. At this point, they had to take drastic measures to increase their population.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

They Were Left With Only One Option

Unfortunately, the Kaw had only one choice to rebuild their tribe: intermarriage. Many Kaw women married White men and got busy having children to increase their population. And while this did raise their numbers, it also severely watered down their bloodline.

But that wasn’t all it did.

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

They Were Educated

Not only did intermarriage with Whites extinguish the true Kaw tribe, it also drastically changed their traditional culture.

By 1910, only one woman in the tribe was unable to speak English—and more than 80% had become literate.

This might seem like progress, and it was, but not necessarily for the Kaw culture.

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

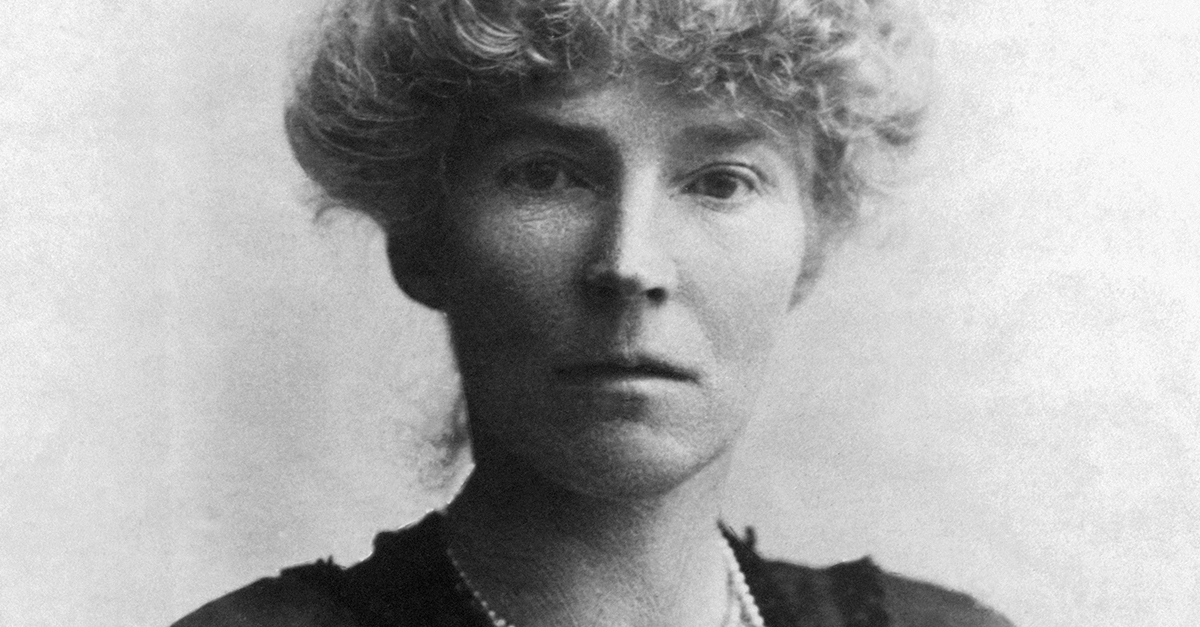

Indian Charley Was Back

Now that the Kaw, and many other Native American tribes, were becoming one with the Americans, the American government expanded their powers over Indian affairs. And you know who was in charge at this point? Our dear friend Indian Charley. He was all grown up and hanging with the big guys now.

Strauss Peyton, Wikimedia Commons

Strauss Peyton, Wikimedia Commons

The Curtis Act Of 1898

Charles Curtis had made it up the pole to Vice President by this time, and he believed that Indians should be assimilated into White culture, and their lands should be divided among their members. Thus, he created The Curtis Act of 1898—and officially started breaking up tribal governments.

He was quite literally squashing his own rights as an Indigenous person.

Harris & Ewing, Wikimedia Commons

Harris & Ewing, Wikimedia Commons

He Gave Himself More

At this time, there were only 247 Kaw tribal members left, and each of them were given 405 acres, of which 160 acres were for personal homesteads. Of course, Curtis himself, along with his son and two daughters, were given 1,620 acres of land.

Sadly, most Kaw sold or lost their land. By 1945, only 13% of the former reservation was owned by Kaw people.

And yet it still managed to get worse.

National Photo Company Collection, Wikimedia Commons

National Photo Company Collection, Wikimedia Commons

They Were Mistreated

The Kaw, who were now left broken and lost, had no official government again until federal recognition and reorganization finally took place in 1959. But even then, the Kaw were among many Native American tribes who became subjected to various forms of mistreatment—including one horrifying act specifically done to Kaw women.

SMU Central University Libraries, Wikimedia Commons

SMU Central University Libraries, Wikimedia Commons

They Tried To Wipe Them Out

During the late 1960s and 1970s, the Indian Health Service (HIS) and collaborating physicians began performing sterilizations on Native American women—in many cases, without free and informed consent. The purpose was to stop the reproduction of Indigenous peoples—eventually wiping out an entire race.

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

They Were Forced

In many cases, this painful procedure was done to women who were perceived as “poor” and “minorities”. Women were often threatened with losing welfare or healthcare if they didn’t agree. Some were told it would be reversible. Some were not told anything at all.

Decades later, the Kaw tribe turned a new leaf.

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

Getting It Back

In 1990, the tribe was able to establish a new tribal constitution and a tribal court. Then, in 2000, the Kaw tribe purchased lands on their pre-1873 reservation near Council Grove, Kansas to create a park commemorating their history.

And while they did slowly rebuild their community—their culture never did recover.

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

A Not-So-Happy Ending

The last fluent speaker of the Kansa language, Walter Kekahbah, died in 1983. And perhaps even more tragically, in 2000, the last full-blood Kaw, William Mehojah, also died. While there may still be Kaw descendants today, there will never be another full-blood Kaw again—essentially making their ancestral culture extinct.

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

'Creator Gives Us Language', thechapmancenter

Kaw Nation Today

Today, there are over 3,000 enrolled members living as close as Kansas, Texas, and Missouri, and as far away as Canada and the United Kingdom. They currently have programs to help their members learn their ancestral language, as well as other traditional rituals and ceremonies.

But as it stands, Kaw Nation will never be the same.

You May Also Like: