Chile’s Fiercest Rebels

The Mapuche have lived in southern Chile and Argentina for thousands of years. Throughout their long history, they have resisted imperial subjugation, first squaring off against the Inca Empire and then holding their own against the Spanish empire.

But the expansion of the colonized world has been impossible to stem, and the Mapuche now find themselves in their most difficult fight yet: protecting their land and way of life from the Chilean government.

Their Population

The Mapuche are the largest of Chile’s 10 Aboriginal groups. There are about 2 million Mapuche people living in the country’s Araucanía region, making up about 10% of the Chilean population. There also about 150,000 Mapuche people living in Argentina.

Where Did They Come From?

The Mapuche are genetically different from other indigenous groups in the region, suggesting they have a different origin. Based on mitochondrial DNA, we know the Mapuche are partially descended from aboriginals in the Amazon Basin.

This suggests they migrated to Chile and eventually became the dominant indigenous group in the south of the country. Archaeological evidence shows they have been living there since 600 to 500 BCE.

Mapuche vs. Inca

The Mapuche were renowned as fierce warriors, which is probably why they didn’t face any real threats until the late 1400s. That’s when the Inca Empire began expanding from Peru into Chile. They managed to subdue the north of the country but ran into problems when it came time to conquer the south—and it was all because of the Mapuche.

A New Name

At the time, the Mapuche were living south of the Maipo Valley. They were fiercely defiant to the Incas’ demands of submission, which led the invaders to call them purumaucas, meaning “savage enemy”. The Inca would learn just how fitting that name was at the Battle of the Maule.

They Weren’t Alone

After refusing to submit to the Inca Empire, the Mapuche called on their allies: the Antalli, Pincu, and Cauqui. When the Incas crossed the Maule River and sent emissaries to the Mapuche, the Mapuche said they would sooner die than give up their freedom. A few days later, they marched to the Inca camp with 20,000 warriors.

Wehinger2014, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Wehinger2014, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Them’s Fighting Words

The Incas tried to smooth things over by claiming that they weren’t there to take the Mapuche’s land, but rather show them how to live like men. But the Mapuche weren’t there for words and told the Inca they would fight until they were victorious or dead.

This didn’t scare the Inca, and they agreed to fight the next day.

Stalemate

With an equal number of warriors, the Inca and the Mapuche (along with their Antalli, Pincu, and Cauqui allies) met each other on the battlefield. At the end of the day, At the end of the day, both sides had suffered serious losses and neither could claim victory over the other.

D. Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga, Wikimedia Commons

D. Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga, Wikimedia Commons

Stalemate (cont’d)

The next two days of battle were as brutal and undecisive as the first. At the end of the third day, both armies had lost more than half their forces. Anyone left alive was injured, so on the fourth day, the Inca and the Mapuche stayed in their fortified encampments, hoping for their enemy to attack the defensive position.

So Who Won?

The Battle of the Maule may have started with lots of bravado, but it ended with a fizzle. The Inca and the Mapuche both refused to leave their camps, so on the seventh and last day of the battle, the Mapuche and their allies decided to go home.

They claimed that they had won the battle—and considering the Inca never pressed into Mapuche territory again, it’s safe to say they were right.

Tuguriodetom, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Tuguriodetom, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

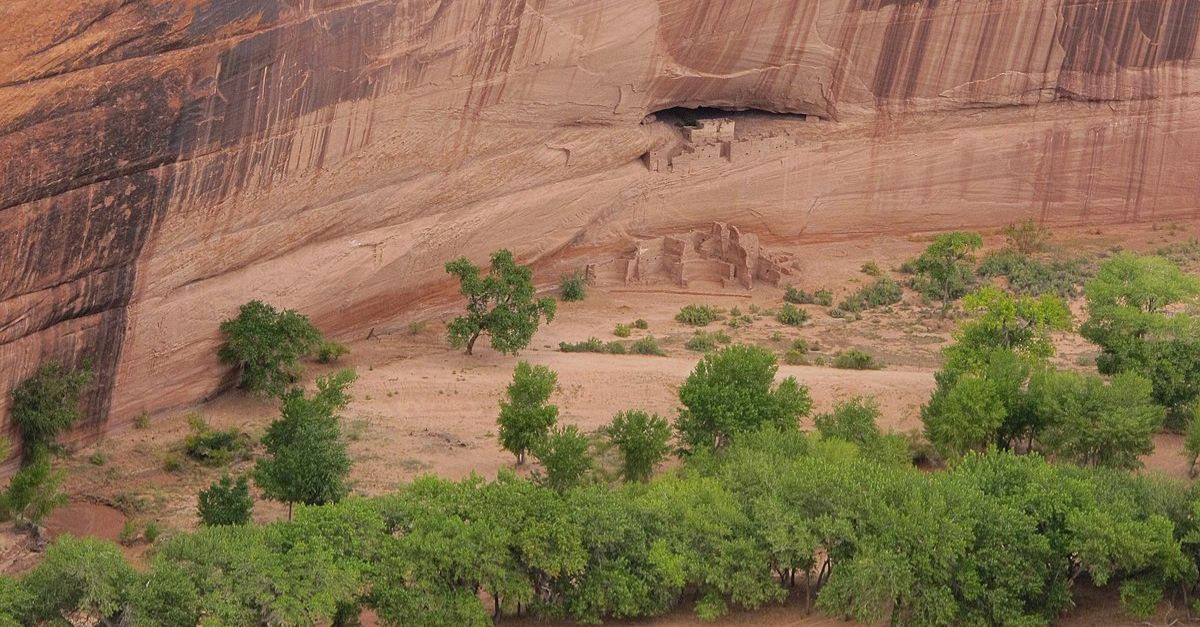

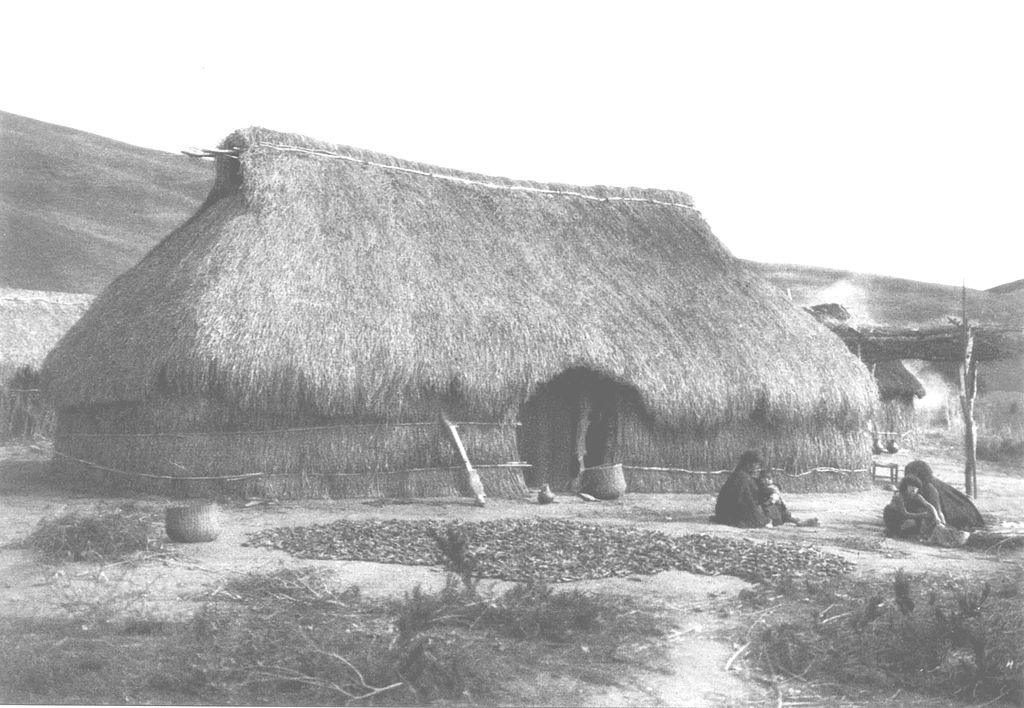

Mapuche Settlements

Prior to contact with the Spanish, the Mapuche lived in scattered settlements which were situated along major rivers and waterways. They usually built their homes on hills instead of plains. This defensive positioning of their houses helped them spot enemies from far away.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Mapuche Settlements (cont’d)

The politics and economy of pre-contact Mapuche villages revolved around family clans and lineages, which were called lof. Though settlements had several lofs, it is believed that they all shared a common paternal ancestor.

Villages often shared a religious altar called a rehue, which is also the term for a confederation of nine villages.

Lin linao, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Lin linao, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mapuche Leaders

Historically, Mapuche communities had two leaders, one secular and one spiritual. The secular leaders were called lonco and were chosen from the wealthiest men in the community.

During times of war, the lonco who were chosen to lead the warriors were called toki. The spiritual leaders were called machi.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Their Name

The name “Mapuche” means “People of the Earth”. This is a fairly recent term which came into use after the Arauco War. Before that, Spanish colonizers called them “Araucanians”, which is now considered by some to be an offensive term.

Mapuche Clans

There are several different groups or clans of Mapuche. They identify themselves based on the geographical traits of their territories. For example, the Puelche are the “people of the east”, the Picunche are the “people of the north”, and the Pehuenche are the “people of the pewen tree”.

The Machi

The machi is a shaman who has a special place in Mapuche society. Machi perform rituals and ceremonies to keep people safe from things like evil or harsh rains.

They also have a deep knowledge of traditional Chilean herbal remedies, which they use along with ceremonies to help cure illnesses. Machi are usually older women, but men can also be machi.

The Rehue

The rehue was both an altar and a shamanic tool. The rehue is made from the trunk of a tree that’s set into the ground. The tree is carved with steps that resemble both a ladder and a human spine. The top of the pillar sometimes has a human face carved into it.

Lin linao, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Lin linao, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Rehue (cont’d)

Every machi has a rehue outside of their house. Sometimes, during ceremonies, the machi will climb the rehue, which helps the machi channel power from spirits called Pillan and from Ngenechen, the most powerful deity in Mapuche religion.

The Pillan

According to Mapuche legends, the Pillan are highly-respected male spirits. Of the Pillan, Antu is the most powerful, and represents the sun and wisdom. Antu is married to Kueyen, the spirit of the moon.

The Pillan (cont’d)

Pillan are usually good, but they can punish the Mapuche by causing natural disasters like droughts, earthquakes, and floods. Every year, the Mapuche perform a ceremony to ask and thank the Pillan for their help.

The Ngen

The Mapuche also believe in nature spirits called Ngen. Ngenechen is the most powerful of those spirits and is the most important deity in modern Mapuche beliefs. Historically, Ngenechen was a not a creator god, but a spiritual leader of the Mapuche.

Since the introduction of Catholicism, Ngenechen is now viewed as a Supreme Being, similar to the Abrahamic God.

What Did They Eat?

When it came to farming, the most Mapuche clans grew their crops in the forest glades. Potato was their staple food, but they also grew quinoa and bred Araucana chickens. The Mapuche were also good fishers and often took advantage of the bounty to be found in Chile’s rivers.

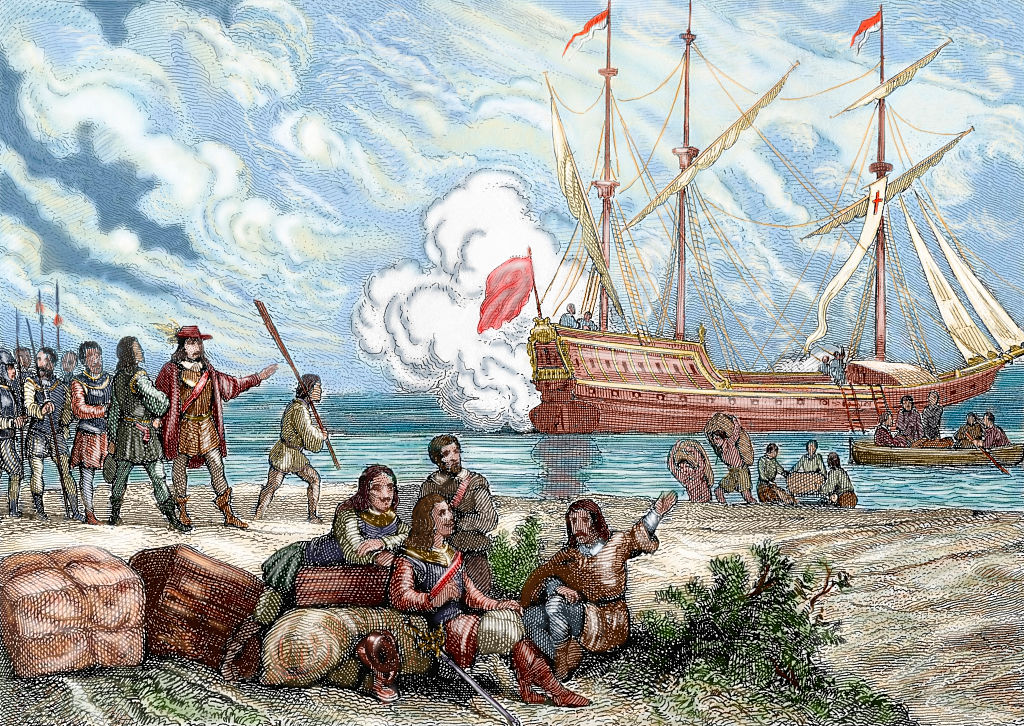

A New Threat

As the Spanish were conquering Peru, they decided to expand into Chile, too. In 1536, a conquistador named Diego de Almagro crossed the Itata River, hoping to begin his conquest of Chile. His hopes were answered when he ran into the Mapuche.

Domingo Mesa, Wikimedia Commons

Domingo Mesa, Wikimedia Commons

The Battle of Reynogüelén

Almagro had brought a force of 200 Spanish calvary and footmen and up to 5,000 Indian auxiliaries. The story goes that they faced off against 24,000 Mapuche warriors. Modern estimates put that at 8,000 Mapuche, but the odds still didn’t look good for the Spanish.

The Battle of Reynogüelén (cont’d)

Luckily for Almagro, the Mapuche were only armed with bows and pikes. These weapons proved to be ineffective against the iron weapons, armor, and horses of the conquistadors.

The Mapuche had never seen these things before and it caused a lot of confusion on their side.

A Decisive Victory

After having all of their assaults repelled by the Spanish, the Mapuche retreated. Many of their warriors had been slain in the skirmish and they left more than a hundred prisoners of war.

While many auxiliaries were killed or wounded, there were only 2 Spanish causalities in the battle.

Fierce Competition

Despite winning the battle, Almagro was shaken by the ferocity of the Mapuche warriors. Between that and the lack of gold or silver in the region, he lost confidence in his expedition to conquer Chile. A year later, he ordered a full retreat to Peru.

Latin America For Less, Flickr

Latin America For Less, Flickr

The Threat Remains

Despite initially scaring off the Spanish, the Mapuche were far from safe. Other conquistadors tried their hand at conquering Chile and were successful in the north of Mapuche territory, which the Spanish called Araucanía.

Pedro de Valdivia was one of those successful conquistadors, and he founded Santiago, Chile’s capital city, in 1541.

Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz , Wikimedia Commons

Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz , Wikimedia Commons

A Different Strategy

The skirmishes between the Mapuche and the Spanish turned into an ongoing conflict, the Arauco War. After losing many battles, the Mapuche changed tactics. They began leaving their fertile crops and moving to remotes places away from the Spanish.

The hope was that the Spanish would start to starve and give up their conquest like Diego de Almagro. While the lack of supplies did cause difficulties for the Spanish, it did little to halt their advance into Mapuche territory.

Pedro Lira Rencoret, Wikimedia Comons

Pedro Lira Rencoret, Wikimedia Comons

Founding Father

In 1550, Pedro de Valdivia was set on conquering Mapuche territory. Following several victorious skirmishes, he founded several cities in the Mapuche’s territory and built the forts of Arauco, Purén, and Tucapel.

Valdivia planned to mine the region’s gold with unpaid labor from the Mapuche—of course, the Mapuche had other plans.

Ccpchile, CC BY-SA 3.0 , Wikimedia Commons

Ccpchile, CC BY-SA 3.0 , Wikimedia Commons

They Adapted

In addition to using guerrilla tactics like ambushes, the Mapuche also used the Spaniards’ tactics against them. In the years since first contact, the Mapuche had learned to ride horses, use wooden shields and armor, and built hilltop forts.

This new knowledge of combat served them well when they took the fight to Valdivia.

Sobrevolando Patagonia, Shutterstock

Sobrevolando Patagonia, Shutterstock

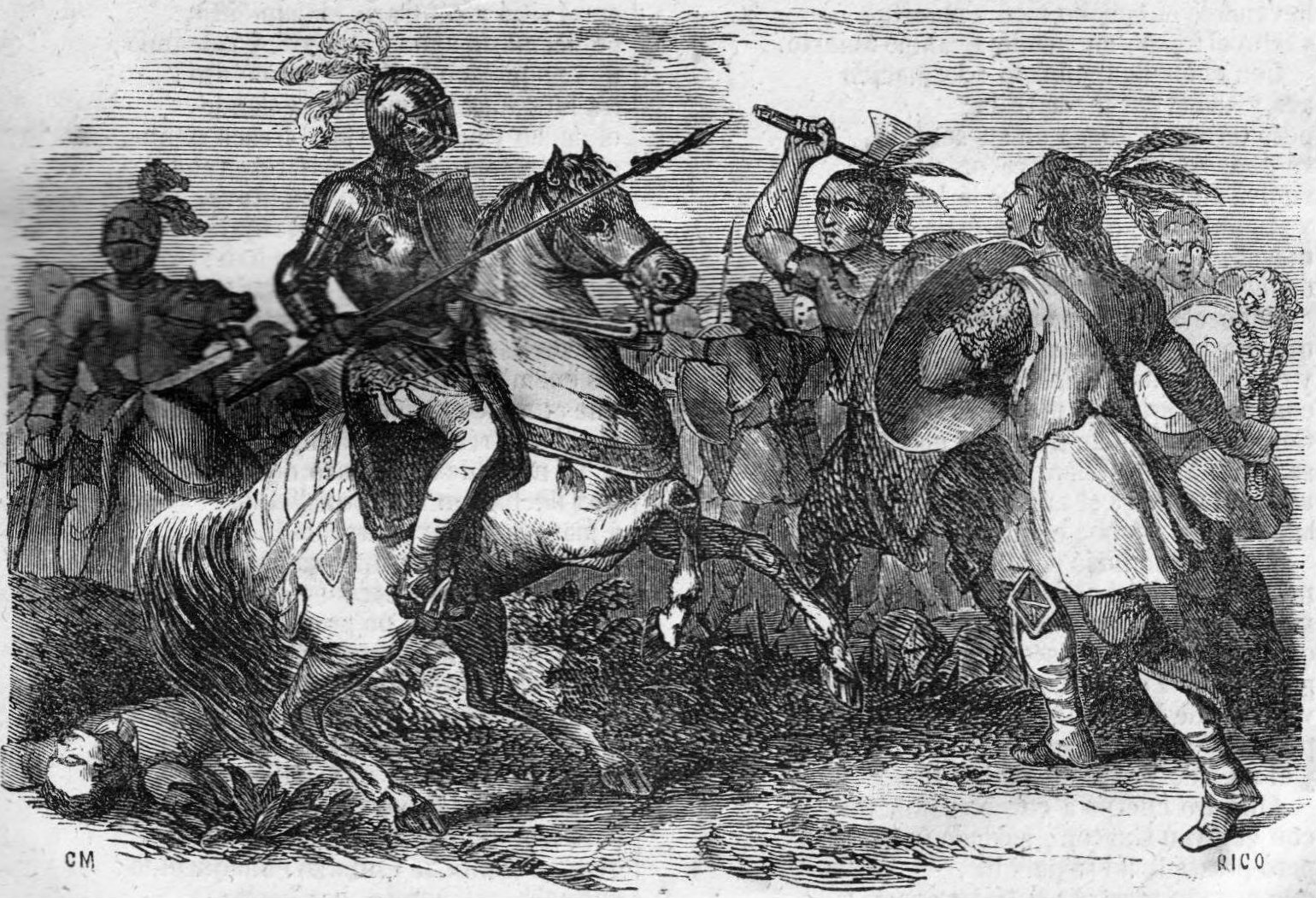

They Fought Back

In 1553, the Mapuche, under the command of Caupolicán and Lautaro, besieged Tucapel fort. Using Spanish battle tactics, the Mapuche destroyed the fort.

Pedro de Valdivia arrived at the fort the next day with 55 Spanish soldiers and 5,000 auxiliaries, but he didn’t stand a chance against the Mapuche, who had at least twice that many warriors.

The Battle Of Tucapel

Attacking in three waves, and armed with maces, ropes, and lances, the Mapuche decimated the Spanish calvary and cut down the auxiliaries. Some of Valdivia’s men tried to escape but they got stuck while crossing the swamps and were taken prisoner by the Mapuche.

The Battle Of Tucapel (cont’d)

At the end of the battle, Pedro de Valdivia was taken captive. He tried to ransom his way out of execution by promising to evacuate the Spanish settlements and give the Mapuche lots of livestock.

The Mapuche refused and executed him with a lance. His head, along with those of his two bravest soldiers, were put on display.

The Mestizos

The Arauco War between the Spanish and the Mapuche would continue for more than a hundred years. In that time, both sides engaged in raids to take slaves and capture women. Eventually, this led to a large population of mestizos, people of Spanish and Indigenous descent.

Jul 24 belize, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Jul 24 belize, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Truce

With high casualties on both sides, the Mapuche and the Spanish eventually learned to live with one another. During a 300-year period of coexistence, the Mapuche were able to retain their political autonomy and eventually began trading with the Spaniards.

A New Regime

The 1800s marked another period of change for the Mapuche. Chile wanted its independence from Spain and many Mapuche clans were ready to join the fight. After the Chilean War of Independence, the Mapuche co-existed with the new regime.

Unfortunately, the peace wouldn’t last.

DEA PICTURE LIBRARY, Getty Images

DEA PICTURE LIBRARY, Getty Images

The Chilean Takeover

In 1861, the Chilean government began to take over Mapuche territories in Araucanía. Many Mapuche were displaced and as poverty in their communities became rampant, the Mapuche came to rely on food rations from the Chilean state.

Claudio Sepúlveda Geoffroy, Flickr

Claudio Sepúlveda Geoffroy, Flickr

Changing Beliefs

The occupation of Araucanía changed Mapuche societies, introducing Christianity and European education. Nowadays, while some Mapuche have held onto their traditions, most have moved to the cities in search of better work opportunities.

But their integration in non-Indigenous society hasn’t made the Mapuche blind to ongoing land disputes with the government.

Stolen Land

In the 1980s, the Pinochet government refused to acknowledge the rights and autonomy of the Mapuche. Land that the Mapuche had regained under the previous Allende government was taken again so that it could be sold for development.

Today, much of the Mapuche traditional territory is controlled by forestry companies—but, as we know by now, the Mapuche aren’t ones to back down from a fight.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Enough Is Enough

The last few years have seen an increase in deadly clashes between the Mapuche and militarized Chilean police. Protests calling for Mapuche land rights and political autonomy have been met with human rights abuses, including killing unarmed Mapuche activists and fabricating evidence against them.

The Rebels

With abuse from the authorities going unpunished, the Mapuche decided to take things into their own hands. In 2021, several skirmishes with Mapuche rebels ended in injuries for Chilean police officers. But the police aren’t the only ones taking heat from the Mapuche.

Take Them All Down

Mapuche rebels have started turning their attention toward logging companies and farming estates. They frequently destroy farm equipment and trucks but have also burned cargo trains and civilian homes.

These attacks have raised awareness for Indigenous rights in Chile, but it’s also led the Mapuche to be branded as terrorists.

Are They Activists Or Terrorists?

The Chilean government has sparked controversy by using the country’s Anti-Terrorism Law to persecute Mapuche activists. Branded as terrorists, activists lose many of their legal rights. Because of this, the United Nations has condemned the Chilean government’s use of the Anit-Terrorism Law against the Mapuche.

Not Everyone Agrees

These violent acts have also led to division among the Mapuche themselves. While they all agree on the goal of gaining their land rights and autonomy, there are many different opinions on the method of achieving that goal. Many Mapuche have denounced violent activists, while others see their moderate counterparts as bootlickers to the Chilean state.

Final Thoughts

While it can be said that the Mapuche rebels have taken extreme steps in their fight to protect their rights, no one can deny the importance of their resistance to a government that seems determined on destroying their way of life. The fight of the Mapuche echoes that of many Indigenous people's around the world and regardless of how it comes about, they deserve to live freely in the lands of their ancestors.