The Dark History Of California’s Gold Rush

In 1848, gold was discovered in California. News spread quickly, and suddenly the state experienced an influx of settlers coming to join the race to riches.

The California Gold Rush is considered by many historians to be the most significant event of the first half of the 19th century—but not just for its fame and fortune.

While it may have brought wealth to many, it brought utter devastation to even more.

The First Speck Of Gold

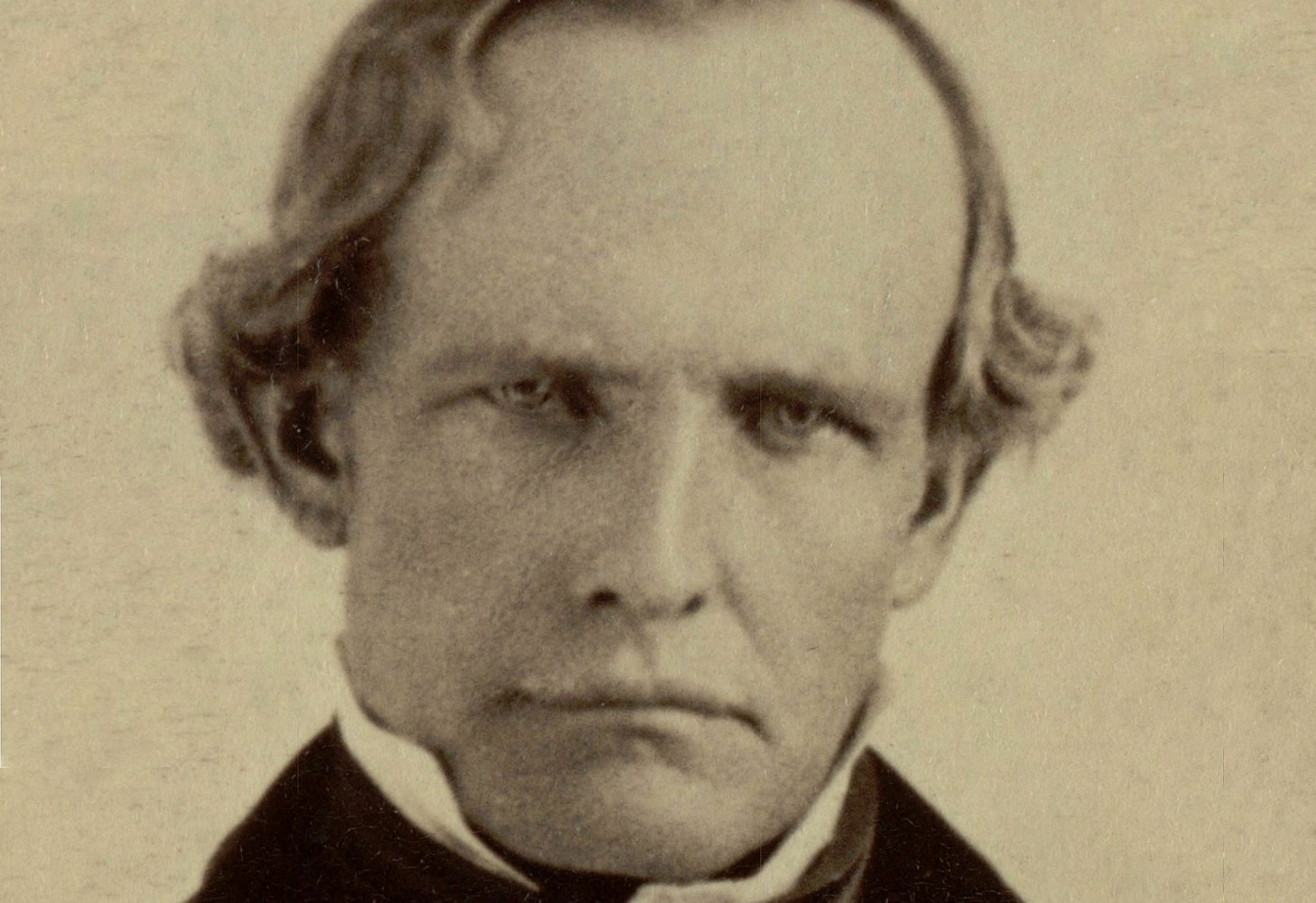

On January 24, 1838, American carpenter and sawmill operator, James W Marshall was building a sawmill when he found shiny golden flakes in a stream off the American River near Coloma, California.

He brought his findings to the mill’s owner, Sacramento pioneer John Sutter, and the two decided to get it privately tested.

But the test results weren’t exactly what Sutter was hoping for.

Scattergood-Sollin, Wikimedia Commons

Scattergood-Sollin, Wikimedia Commons

Unfortunately, It Was Real

When the test came back that the sample was indeed gold, Sutter expressed some disappointment. While he was undoubtedly excited to have found real gold, he knew that such a discovery would come with some major complications—particularly for his plan to build an agricultural empire.

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Keeping It Hush Hush

Sutter’s fear was that if there were a gold rush in the region, his plans for his nearly-built water-powered sawmill would come to an immediate halt.

He managed to convince Marshall, and any other crew who were around for the discovery, to keep the gold a secret. The pair became partners, and decided on next steps.

Frank Buchser, Wikimedia Commons

Frank Buchser, Wikimedia Commons

Securing Rights To The Land

A few weeks later, Sutter sent his colleague, Charles Bennett, to Monterey to meet with Colonel Mason, the chief US official in California, to secure the mineral rights of the land where the mill stood—and where the gold was found.

Bennett was under strict orders to keep his lips sealed about the gold—but he wasn’t exactly great at keeping secrets.

R. H. Vance, Wikimedia Commons

R. H. Vance, Wikimedia Commons

Spilling The Beans

When Bennett stopped at Benicia, he overheard talk about a coal discovery near Mount Diablo, and when he saw how excited people were, he, without thinking, blurted out the discovery of gold.

If that wasn’t bad enough, he continued on his journey, spilling the beans the entire way.

Bobak Ha'Eri, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bobak Ha'Eri, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Got Denied

By the time Bennett got to Monterey, he had already spread the story to more than a few people. And when Colonel Mason declined the rights to the land, Bennett, for the third time, revealed the secret about the gold—and that was only the beginning of the nightmare.

U.S. Army Signal Corps, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Army Signal Corps, Wikimedia Commons

Smart Thinker

By March, the rumors were confirmed by San Francisco newspaper publisher and merchant Samuel Brannan—who then went on to quickly set up a shop that sold gold prospecting supplies (which would later end up being the best decision he ever made).

Not only that, he was a walking advertisement—literally.

Eliza Poor Donner Houghton, Wikimedia Commons

Eliza Poor Donner Houghton, Wikimedia Commons

Calling All Gold-Seekers

Brannan actively advertised the gold by walking through the streets of San Francisco, parading a vial of gold, shouting "Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!"

More and more people became intrigued, and word spread faster than wildfire.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

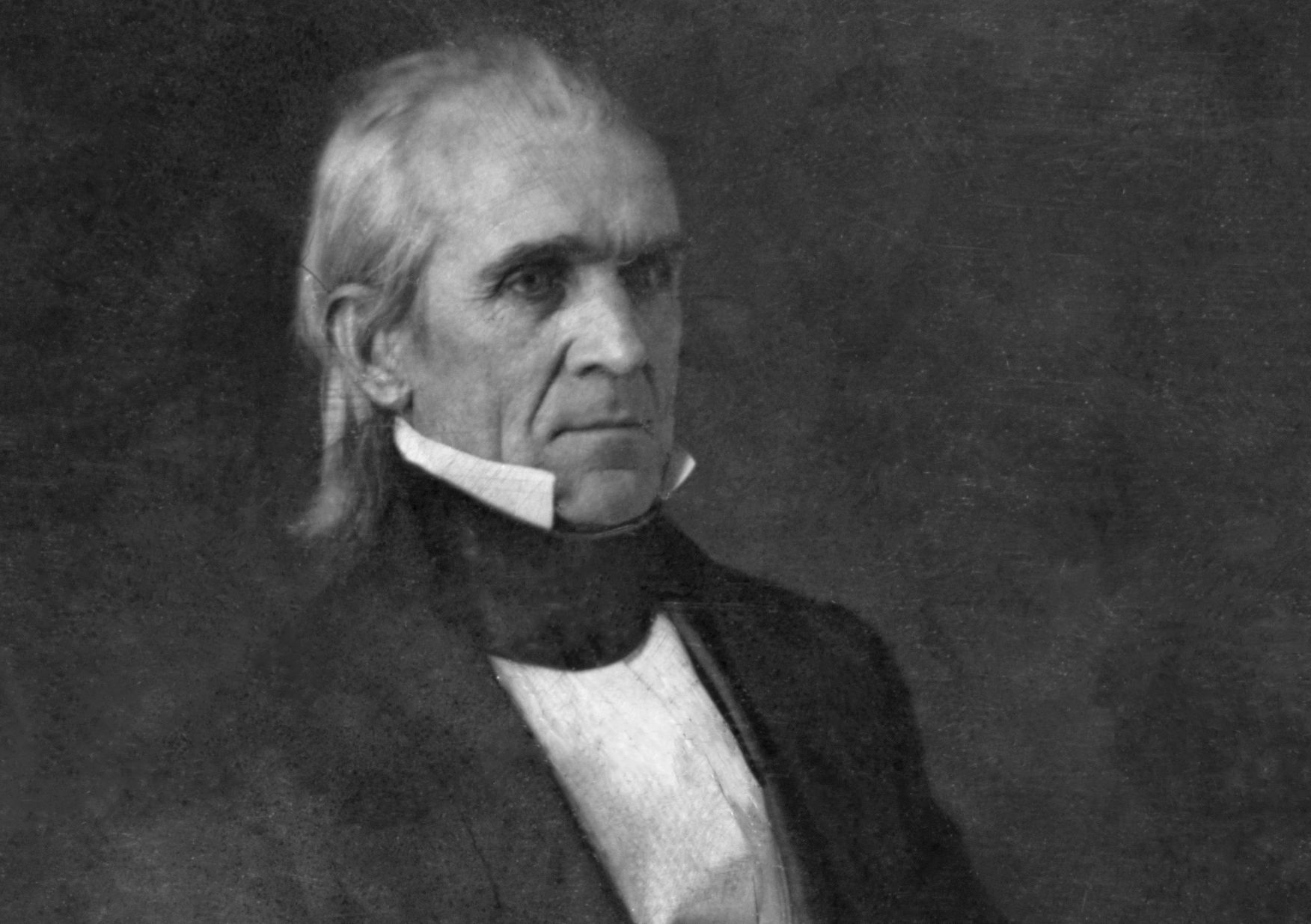

Officially Public News

On August 19, 1848, the New York Herald was the first major newspaper on the East Coast to report the discovery of gold. And by December 5th, US President James K Polk made the official confirmation of the discovery while addressing Congress.

It was then that the public made a stark realization.

Brady, Mathew B, Wikimedia Commons

Brady, Mathew B, Wikimedia Commons

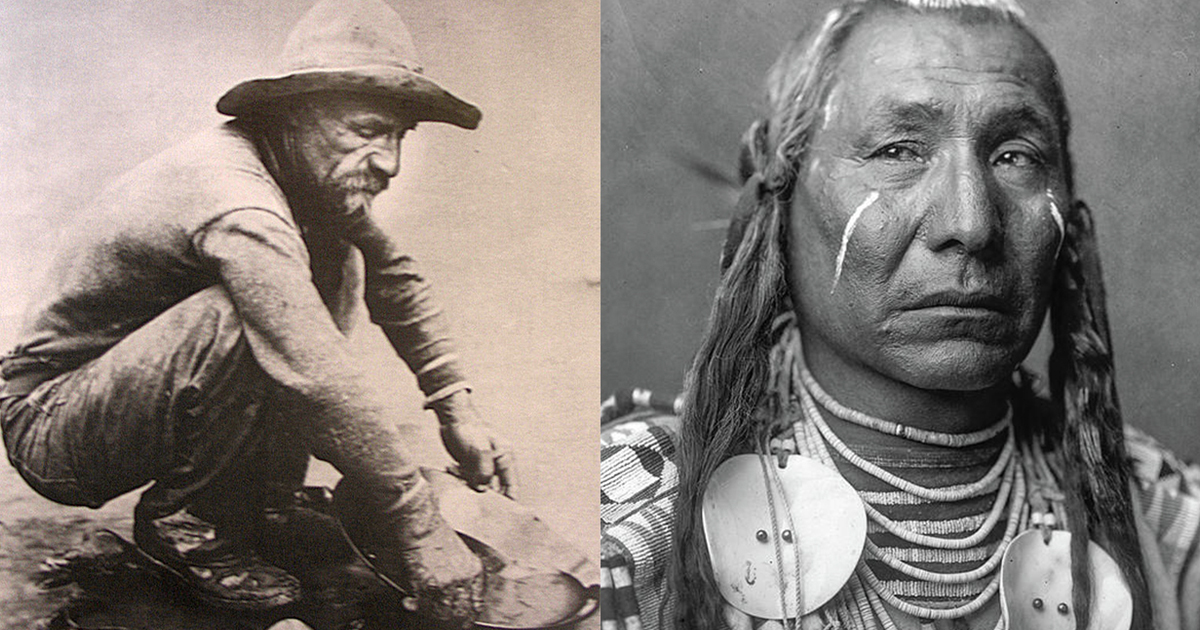

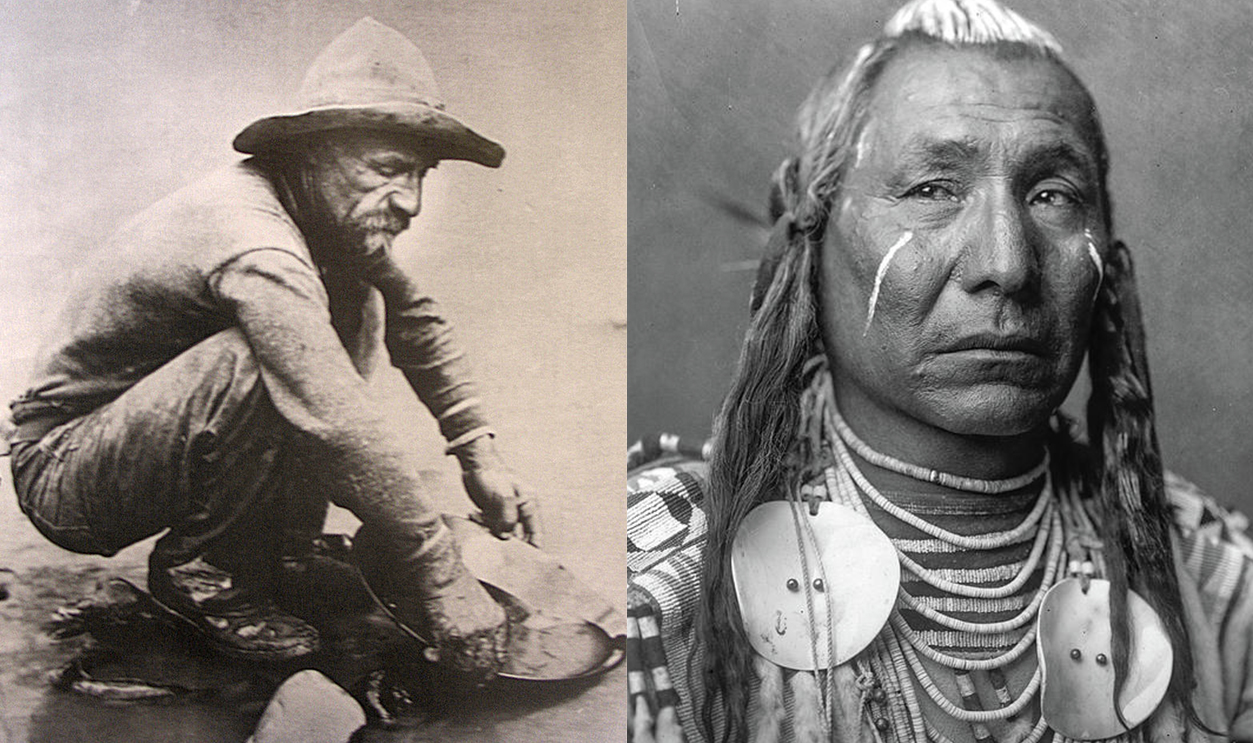

Introducing The Forty-Niners

Not long after the President’s confirmation, the general public realized that there was a real potential for wealth—and that basically anyone could get in on it.

It was then that anyone looking to benefit from the gold rush—later called the “forty-niners”—began moving to the Gold Country of California (also referred to as the “Mother Lode”).

California State Library, Wikimedia Commons

California State Library, Wikimedia Commons

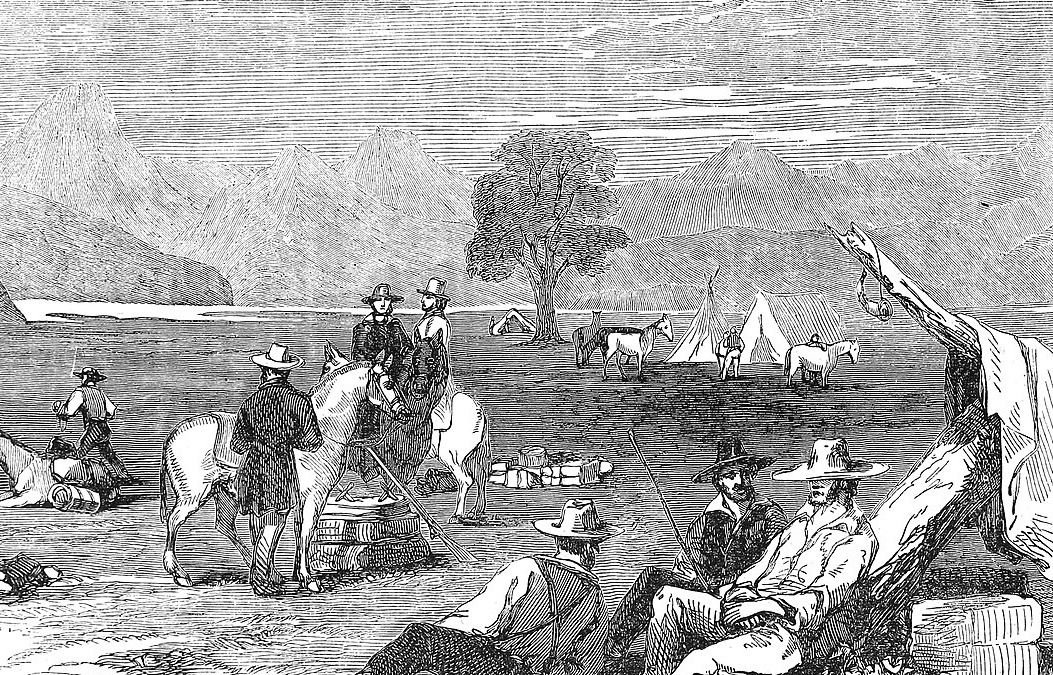

Word Traveled Fast

The forty-niners didn’t just come from other parts of the United States. Word had spread worldwide, and people were now migrating from all corners of the globe, in hopes of becoming rich.

And, just as Sutter had predicted, things went south—fast.

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Sutter’s Downfall

Sutter’s business plans for his sawmill were instantly squashed. His workers had all up and left him to join the search for gold. And then squatters took over his land and stole all of his crops and cattle.

His entire business had gone under, and while everyone else was on hunt for riches, he ended up bankrupt. And he wasn’t the only one.

From Rags To Riches

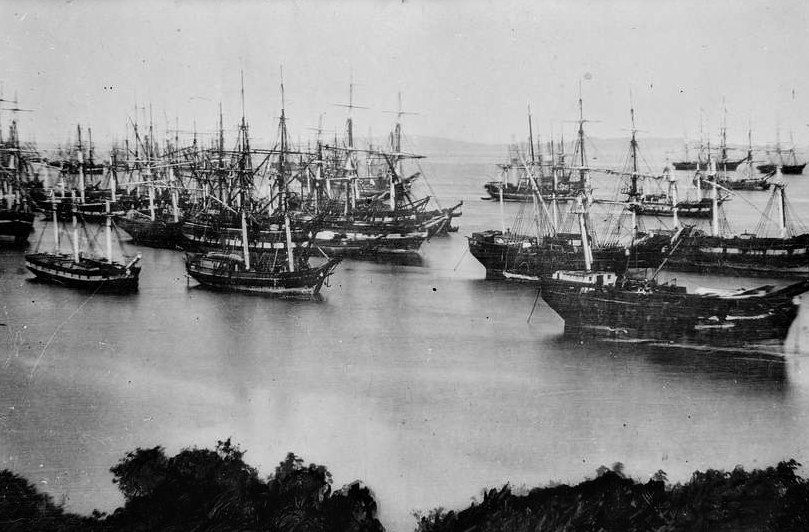

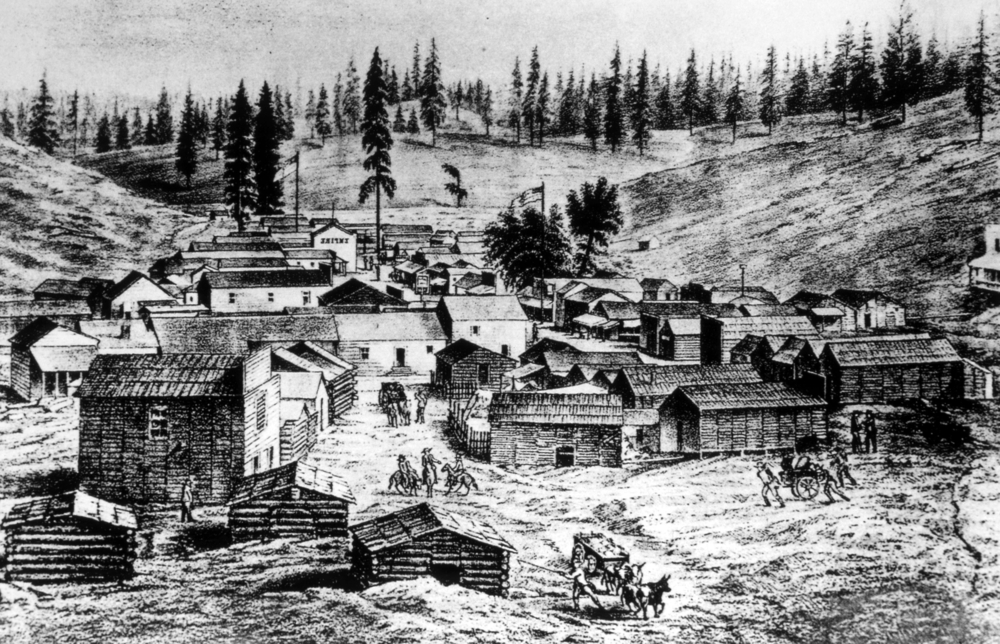

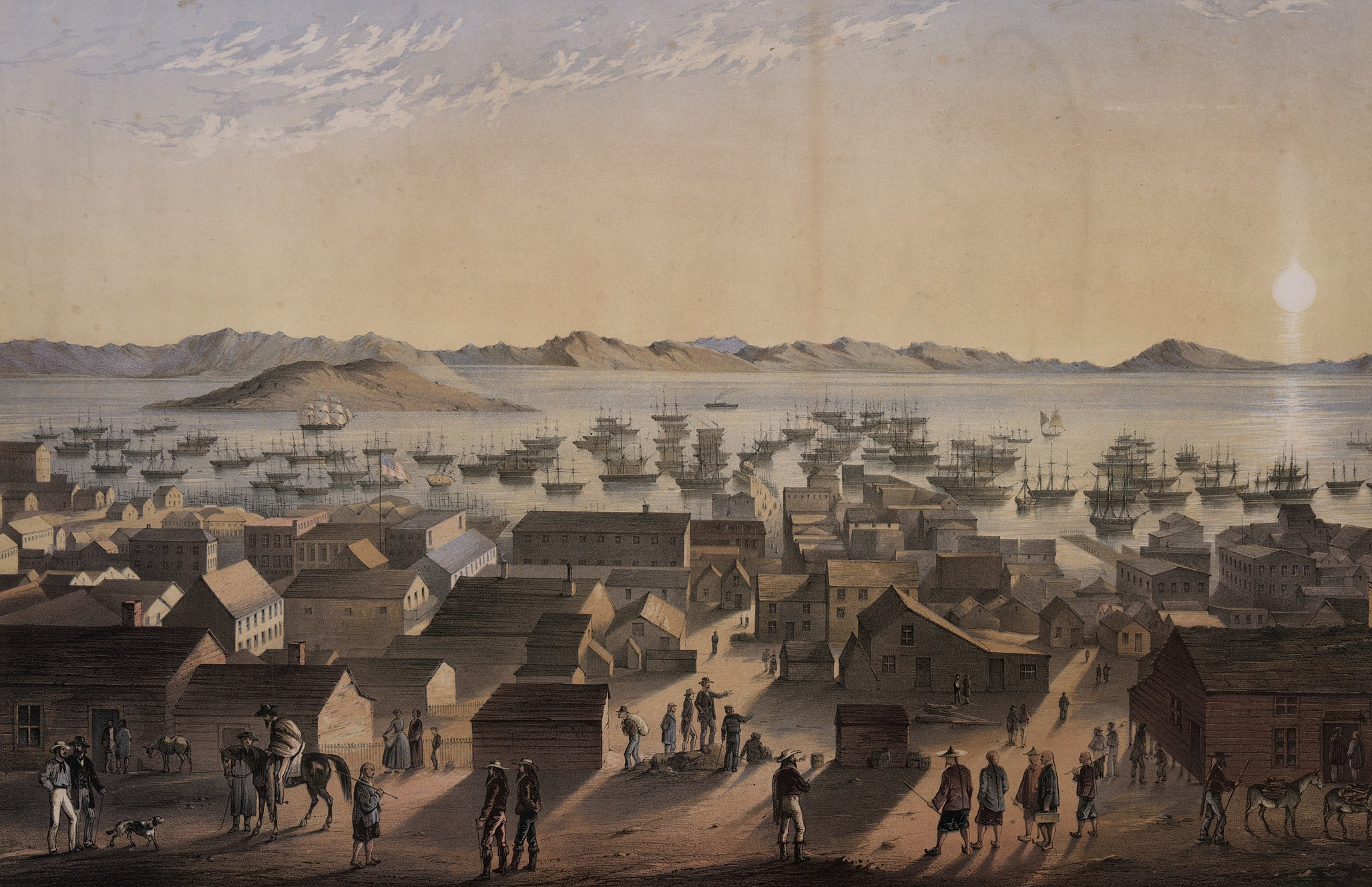

Before all of this began, San Francisco was nothing more than a tiny, sleepy settlement. When residents learned about the discovery, it at first became a ghost town of abandoned ships and businesses when people suddenly left to join the other miners, but then suddenly boomed as merchants and new people arrived.

The population didn’t just double or triple, it grew by immense proportions.

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

A Boom In Population

The population of San Francisco quickly went from 1,000 in 1848 to 25,000 full-time residents by 1850.

People had impulsively moved there, many without a plan. Because of this spontaneous decision, most immigrants lived in tents, wood shanties, or deck cabins removed from abandoned ships.

There were also no churches or religious services in the rapidly growing city—but that didn’t last long.

National Parks Gallery, Picryl

National Parks Gallery, Picryl

Missionaries Saw An Opportunity

Missionaries took advantage of the situation and quickly joined the others in San Francisco, looking for ways to bring God to the people. One particular man, William Taylor, held services in the street using a barrelhead as his pulpit.

Crowds would gather to listen to his sermons, and before long, he received enough generous donations from successful gold miners and built San Francisco's first church.

They may have found faith, but they were still living in the dirt. And getting there was no feat, either.

Cox, George Collins, Wikimedia Commons

Cox, George Collins, Wikimedia Commons

Getting To The Gold, At All Costs

This event has been referred to as the “first world-class gold rush,” and people took it very seriously. In the US alone, many people were borrowing money, mortgaging their homes, and spending their life savings just to find a way to get to California.

The thought that a person could change their whole life by simply collecting gold off the ground was an irresistible idea—but the journey was not for the weak.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

A Dangerous Journey

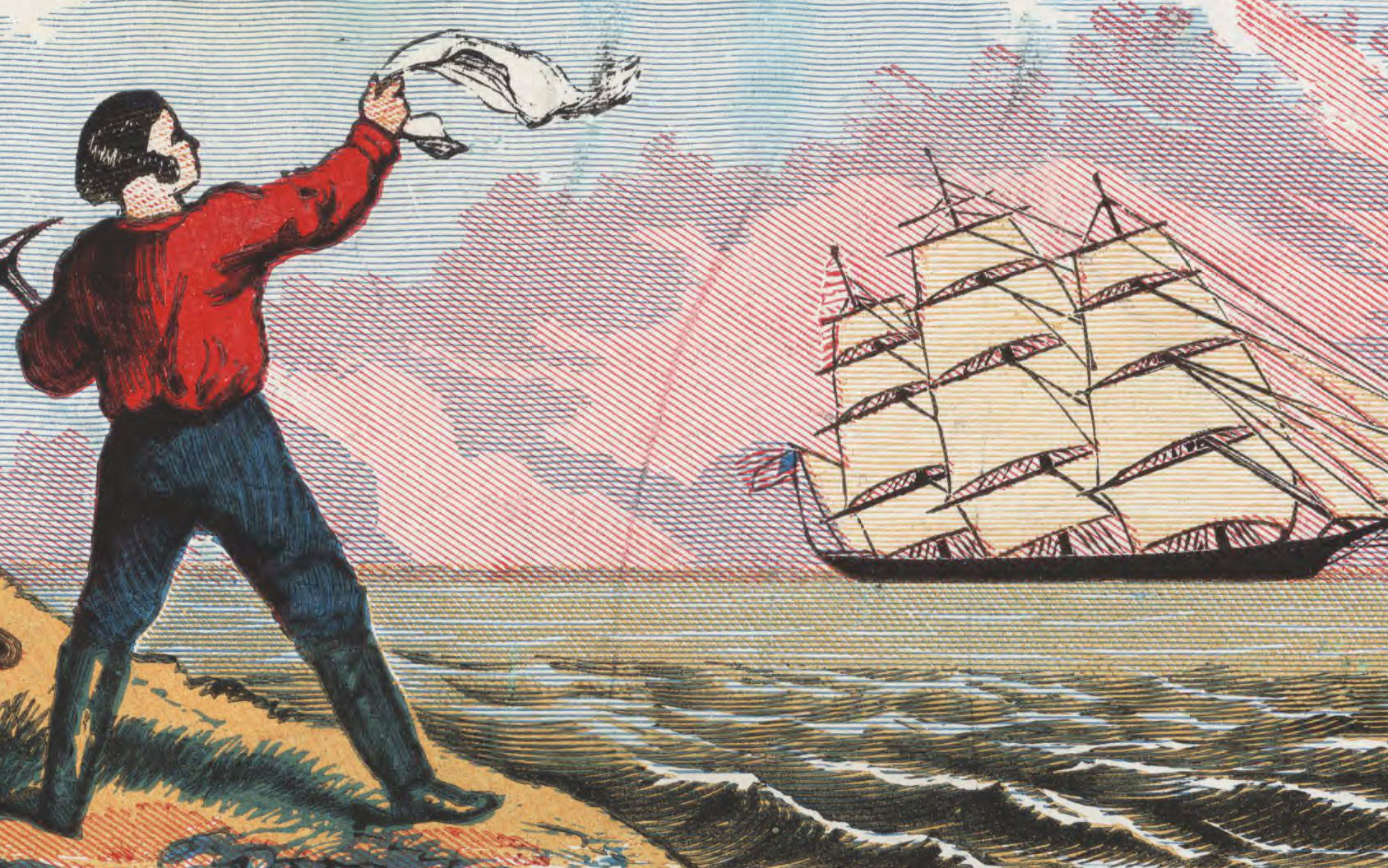

At this time, California was not exactly easy to get to—especially for international travelers. Not only was the journey a long one, it was incredibly dangerous. Forty-niners faced immense hardship and often death along the way.

Traveling By Sea

At first, most people traveled by sea. But from the East Coast, a sailing voyage around the tip of South America would take four to five months—if all went well. During this time, many travelers perished from starvation, exposure to the elements, violence, accidents, and disease.

G.F. Nesbitt & Co., Wikimedia Commons

G.F. Nesbitt & Co., Wikimedia Commons

Taking The Scenic Route

The other option was to sail the Atlantic side of the Isthmus of Panama, then take canoes and mules for a week through the jungle, and then on the Pacific side, wait for a ship sailing for San Francisco. This trip had all the same dangers, plus a few exotic threats as well.

As crazy as it sounded, people still did it—but the sea wasn’t the only route.

Charles Christian Nahl, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Christian Nahl, Wikimedia Commons

Traveling By Land

Many gold-seekers used the overland route as well, particularly along the California Trail. But this route wasn’t any safer. Many people didn’t make the journey, whether they went from land or sea. Deadly hazards were everywhere, from shipwrecks to typhoid fever and cholera, it’s no wonder the forty-niners were mostly all men.

General Land Office. U.S, Wikimedia Commons

General Land Office. U.S, Wikimedia Commons

Leaving The Women Behind

Knowing the journey to be treacherous, most families chose to send the men and leave the women and children at home. However, this didn’t make things any easier. On the home front, women were left to pick up the pieces after their husbands took all their money and left them with nothing but mere hope that they'd someday return rich.

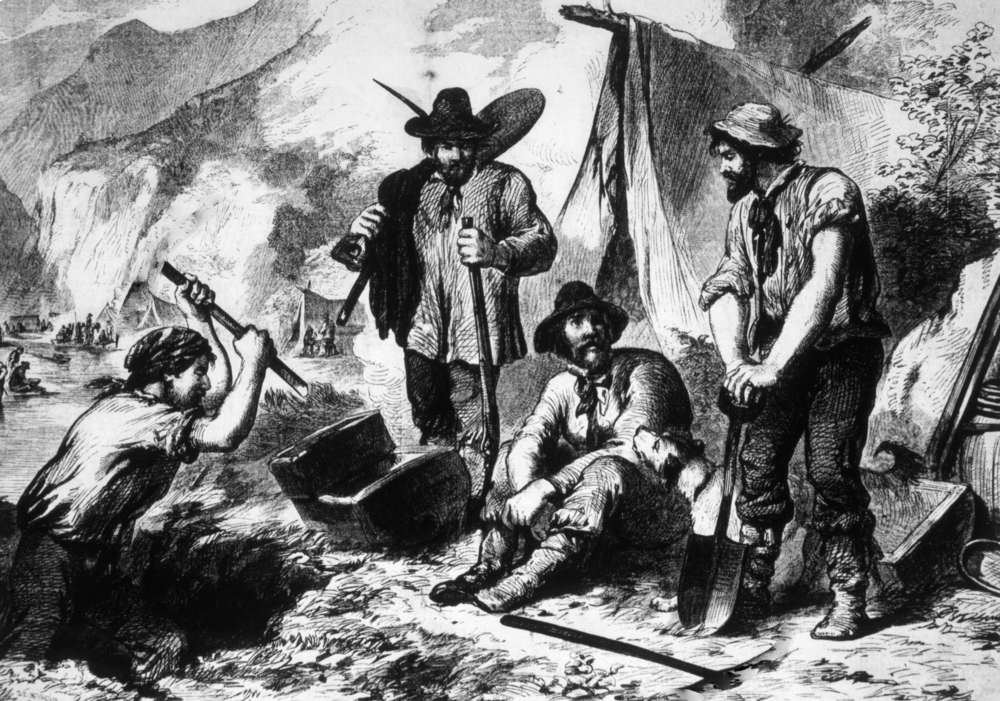

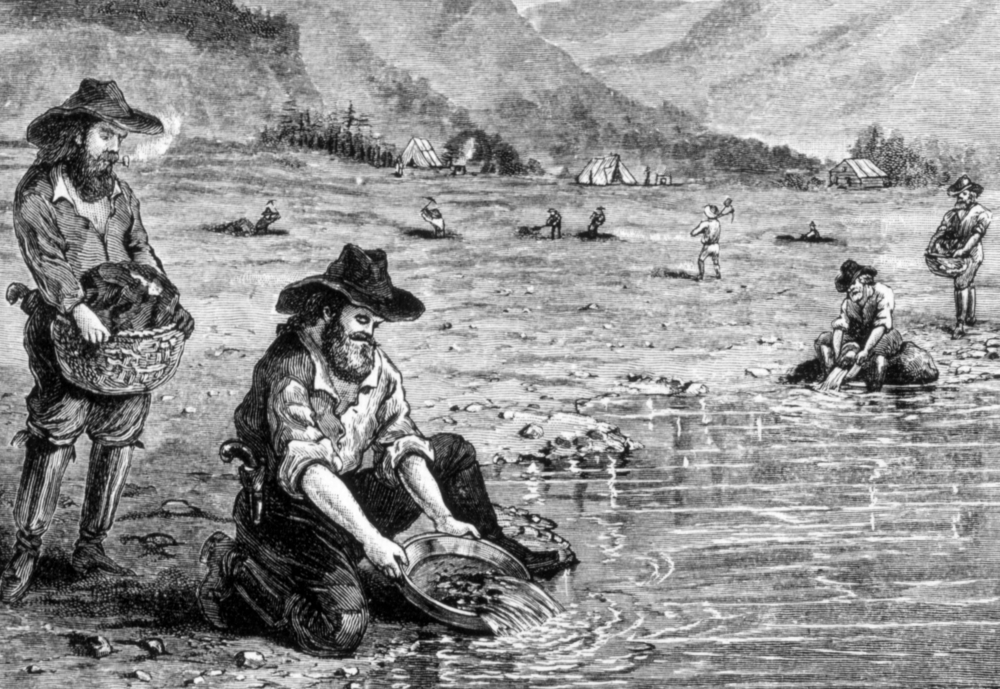

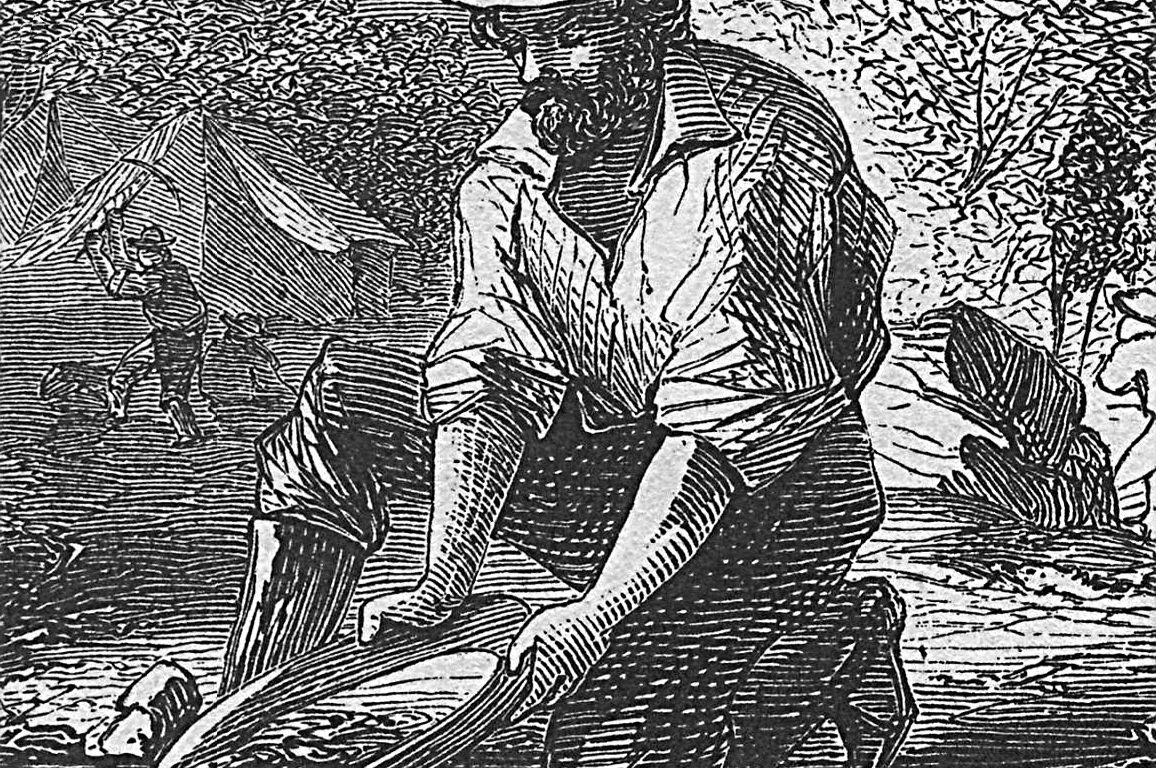

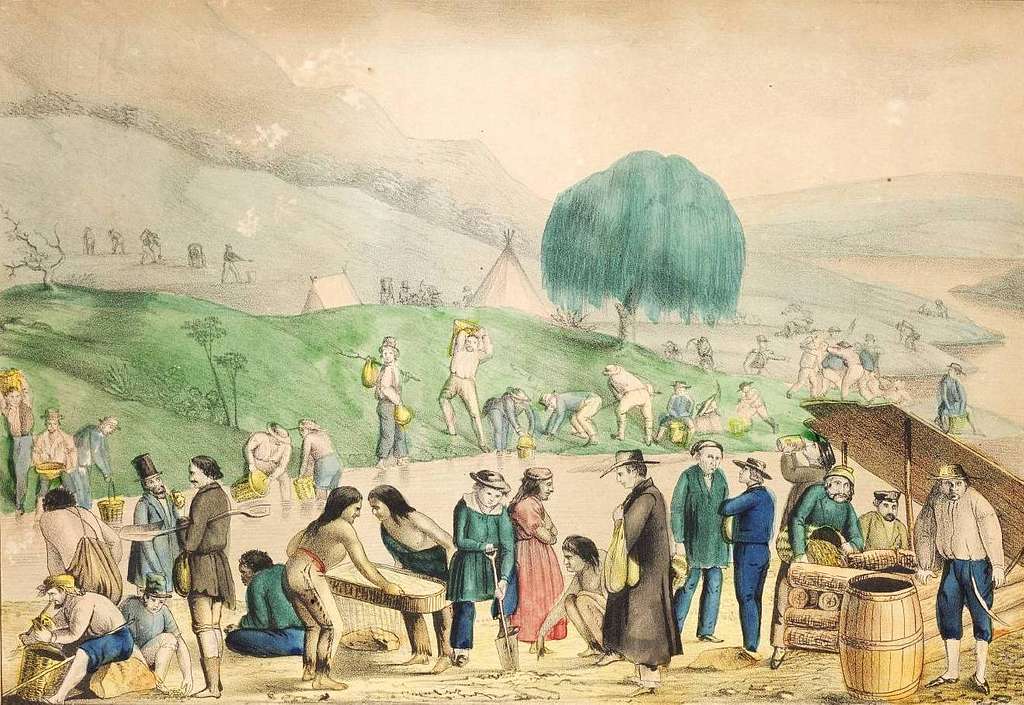

No Relief Upon Arrival

The people who made it to California alive were not exactly relieved once they got there. After a nearly impossible excursion, they were then tasked with the brutally physical job of actually finding gold.

And it was more painful than many realized.

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

The Hardest Kind Of Labor

Since most miners were inexperienced and undersupplied, they quickly learned that mining was the hardest kind of labor. They moved rock, dug dirt, and waded into freezing streams of water. Many lost fingernails, dug their hands down to bloody bone, got sick, and suffered malnutrition.

A lot of forty-niners sadly lost their lives from diseases and accidents.

George H. Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

George H. Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

Keep Your Eyes On The Prize

One man named Hiram Pierce, a miner from Troy, New York, held a small, unofficial funeral for a young man from Maine who died of gangrene after carelessly shooting himself in the leg by accident.

But even though the work was relentless, the promise for a payout continued to draw in more miners each year.

L. C. McClure, Wikimedia Commons

L. C. McClure, Wikimedia Commons

The Elite Have Arrived

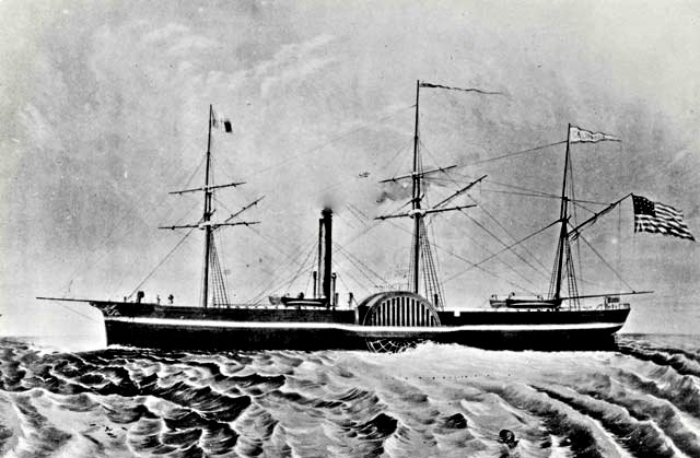

By 1849, the non-native population of California had grown to almost 100,000 people. Nearly two-thirds were Americans. And many of the arrivals came by steamship—which was certainly the more luxurious route to take.

Marryat, Frank, Wikimedia Commons

Marryat, Frank, Wikimedia Commons

Luxury Steamships

Most steamships from the Eastern Seaboard required the passengers to bring kits—which were typically full of personal belongings such as clothes, guidebooks, tools, etc.

But they were also required to bring barrels of food, such as beef, biscuits, butter, pork, rice, and salt—and most who took this ship were able to do so.

The travelers who could afford this style of transportation were able to enjoy mingling conversation, smoking, fishing, and even gambling, depending on the ship.

The Cheaper Option

The cheaper steamships usually had longer routes and less accommodations. And each steamship segregated people based on wealth and power—basically separating the rich from the poor.

But passenger ships weren’t the only naval operations dominating the waters.

US National Postal Museum, Wikimedia Commons

US National Postal Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Creating An Economy

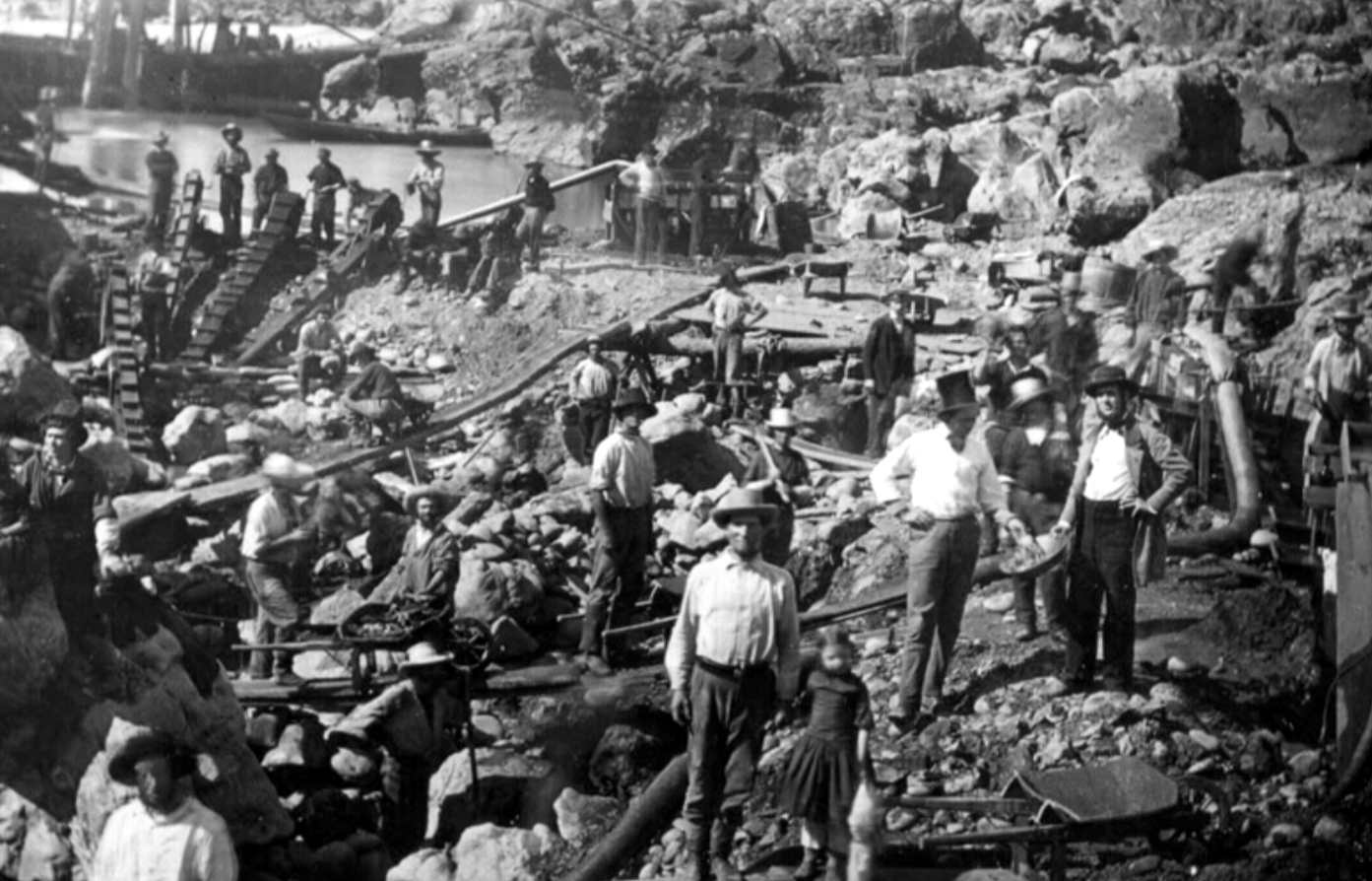

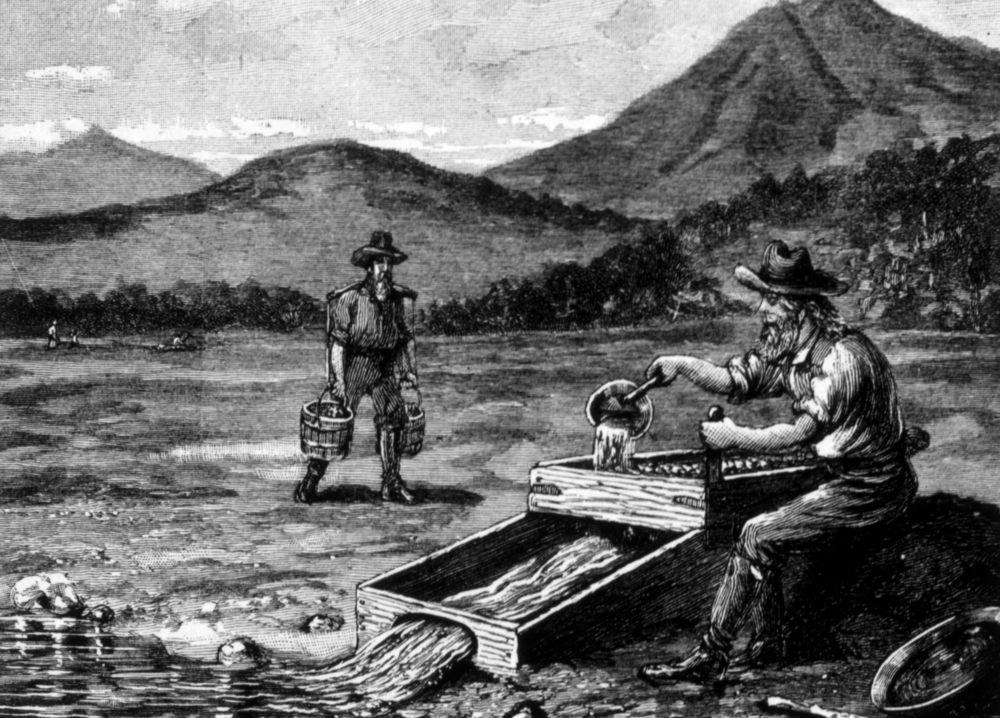

Supply ships became increasingly needed to bring goods to the ever-growing population in California. By 1848, about 4,000 gold miners were in the area. Only one year later, that number rose to 80,000 and by 1853, the population had reached a whopping 250,000.

It didn’t take long for settlers to build.

George H. Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

George H. Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

Becoming California

When news first broke of the discovery, hundreds of ships were abandoned after their crews deserted to go after the gold themselves. Many of those ships were then converted into warehouses, stores, taverns, hotels, and even jails.

Eventually, the region expanded and the little port of San Francisco became a lively city with a busy economy, and California was named the 31st state.

But this budding metropolis was not without its downfalls.

Targeting Foreigners

While the majority of the gold-seekers were Americans, there were still a number of people who came from overseas—and many of them became targets simply for being foreigners.

Eadweard Muybridge, Wikimedia Commons

Eadweard Muybridge, Wikimedia Commons

Chinese Immigrants

By 1852, about 20,000 Chinese immigrants landed in San Francisco. Their distinctive dress and appearance were highly recognizable in the goldfields, and they ended up suffering enormously, enduring violent racism from White miners who directed their frustrations at foreigners.

But race wasn’t the only challenge.

Graves, Roy Daniel, Wikimedia Commons

Graves, Roy Daniel, Wikimedia Commons

From Wives To Widows

Women were also involved in the gold rush—though their numbers were still small. Of the 40,000 people who arrived by ship in 1849, only 700 were women. They ranged from poor to wealthy. Some were entrepreneurs and some used their bodies for work; some were single and some were married.

Some women came with their husbands and others were sent for by their husbands. But many of the married women quickly became widows—either during the journey or shortly afterward.

And disease wasn’t the only way people lost their lives.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Blurred Lines

When the gold rush began, the goldfields were basically lawless. At the time, Sutter’s Mill, California was still technically part of Mexico—under American military occupation as the result of the Mexican-American War.

With the signing of the treaty ending the war on February 2, 1848, California became part of the US, but it was not yet a formal “territory".

Basically, it existed as a region under military control—and this was more than a little confusing for residents.

Harper's Magazine, Wikimedia Commons

Harper's Magazine, Wikimedia Commons

A Lawless Society

Since it was under military control, there was no civil legislature and no judicial body in the entire region. Local residents used a confusing and changing mixture of Mexican rules, American principles, and personal dictates.

With essentially no laws, you can imagine how miners handled disputes.

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Free For The Taking

With no legal rules and no security or enforcement, the gold was simply “free for the taking” at first. There was no private property, no licensing fees, and no taxes. Because of this, the miners informally adapted Mexican mining law that had existed in California at the time.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Mexican Mining Law

The Mexican mining law attempted to balance the rights of early arrivers at a site with later arrivers. A “claim” could be “staked” by a prospector, but that claim was valid only as long as it was being actively worked.

And it was imperative that miners determine the claim’s potential—and quickly.

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Claim-Jumping

Miners would work at a claim only long enough to determine its potential. If it was deemed as low-value—as most were—miners would then abandon the site in search for a better one.

And when that happened, other miners were free to “claim-jump” the land. But this often led to some serious disputes.

Oakland Museum of California, Wikimedia Commons

Oakland Museum of California, Wikimedia Commons

Violent Disputes

Since there was no way of enforcing these rules, or monitoring claim-jumps, disputes were common. And they were not exactly handled well. Most disputes were handled personally and violently—with many miners losing their lives as a result.

This already-competitive job only got worse as the region became more crowded, and there was less gold to go around.

The Peak Of The Gold Rush

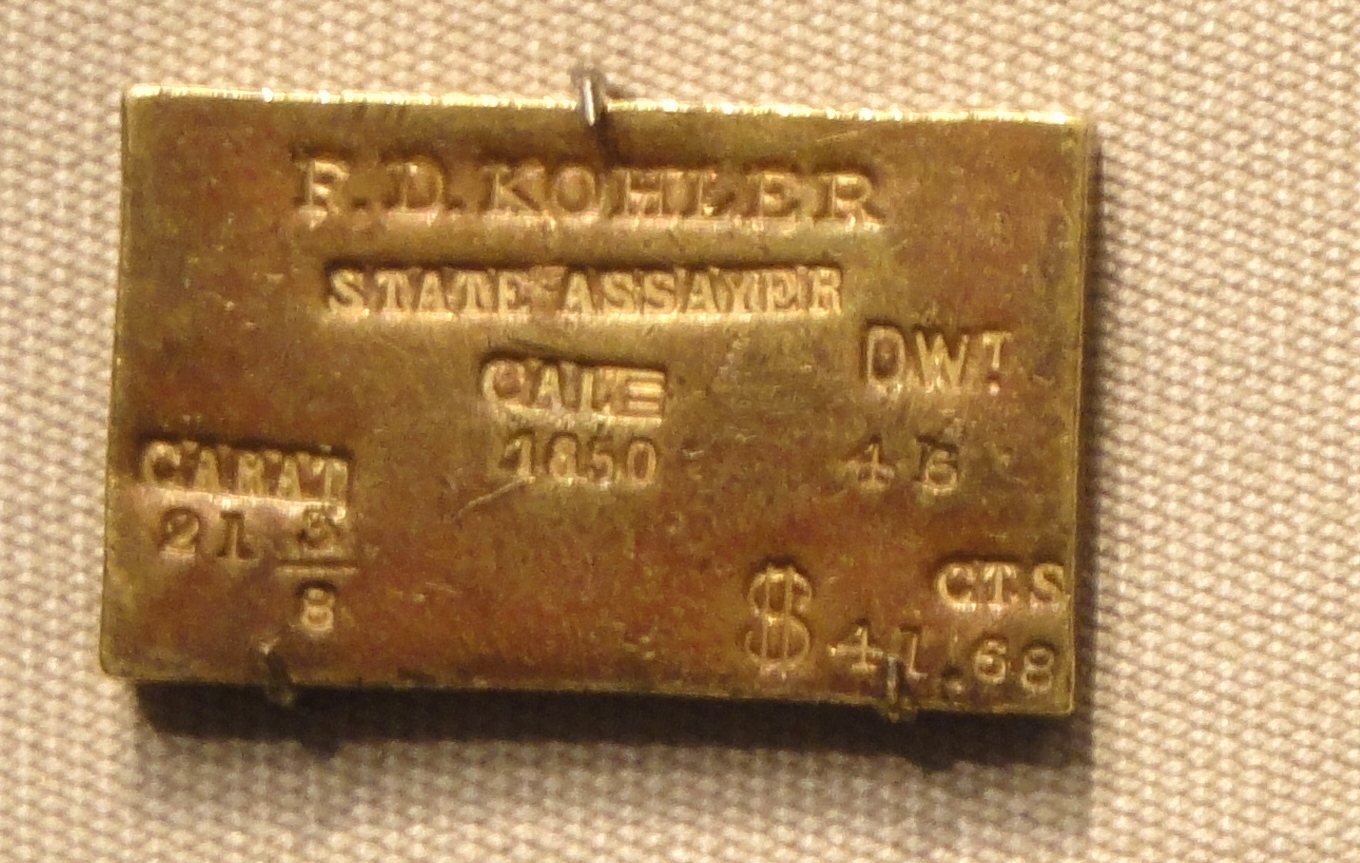

In 1849 alone, an astounding $10 million worth of gold was dug out of the ground (which is equal to nearly $500 million in 2024). But in 1850, another $41 million worth of gold was uncovered.

That number only increased more and more each year, with $75 million in 1851 and $81 million in 1852.

But as the gold continued to flow, the competition continued to grow—and things took a hostile turn.

Too Much Of A Good Thing

Although the gold rush did actually bring an unthinkable amount of wealth to a lot of people, it also propelled California from a sleepy, little-known region to the global imagination of hundreds of thousands of people.

In the midst of it all, towns and cities were created, California became an official state, and large-scale agriculture began, making space for roads, schools, churches, and civic organizations.

The gold rush was putting California on the map—but as we know, too much of something is not always a good thing.

Gustave-Adolphe Chassevent-Bacques, Wikimedia Commons

Gustave-Adolphe Chassevent-Bacques, Wikimedia Commons

Greed Was Seeping In

As the mining region grew more crowded, Anglo-American miners became increasingly territorial over land they viewed as meant for them. They started violently forcing other nationalities from the mines—including people who actually had rights to the land.

J. H. Richardson, Wikimedia Commons

J. H. Richardson, Wikimedia Commons

Human And Environmental Costs

The human and environmental costs of the gold rush were substantial. Native Americans, who were dependent on traditional hunting, gathering, and agriculture, became victims of starvation and disease.

Gravel, silt, and toxic chemicals from prospecting operations killed fish and destroyed habitats, leaving Native Americans with a quickly deteriorating homeland. And that wasn’t even the worst of it.

Denver Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

Denver Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

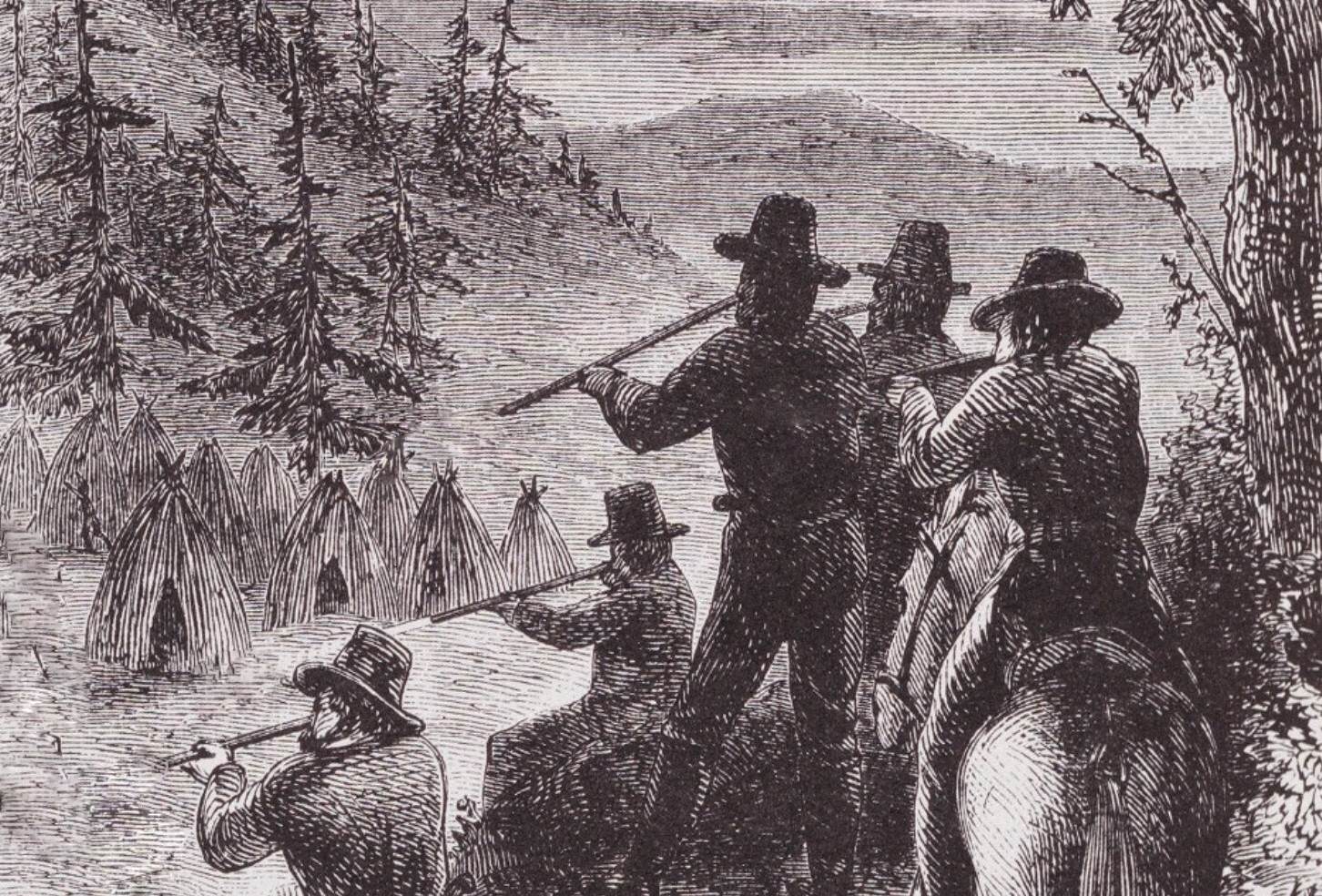

Attacks On Native Americans

In some areas, regular attacks against the local indigenous people occurred, which then turned into various conflicts fought between Natives and settlers. Miners often saw Native Americans as “in the way,” and had no problem ending their lives to remove them.

There were times when miners would take out at least 50 or more Natives in one day. And when the Natives fought back—it got so much worse.

John Ross Browne, Wikimedia Commons

John Ross Browne, Wikimedia Commons

Retribution Attacks

Sometimes, the Native Americans would fight back. They would usually target solo miners, but then that was only met with something worse. Eventually, retribution attacks resulted in entire tribes and villages being attacked—including innocent women and children.

All in the name of greed.

NorCalHistory, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

NorCalHistory, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Bridge Gulch Massacre

In 1852, during what is now known as The Bridge Gulch Massacre, a group of settlers attacked a band of Wintu Natives in response to the killing of a citizen named JR Anderson.

After his demise, the sheriff led a group of men to track down the Natives and take their lives. About 150 Wintu people were brutally slain—with only three young children (who were part of a different band of Wintu) surviving.

And this wasn’t the only horrific massacre either.

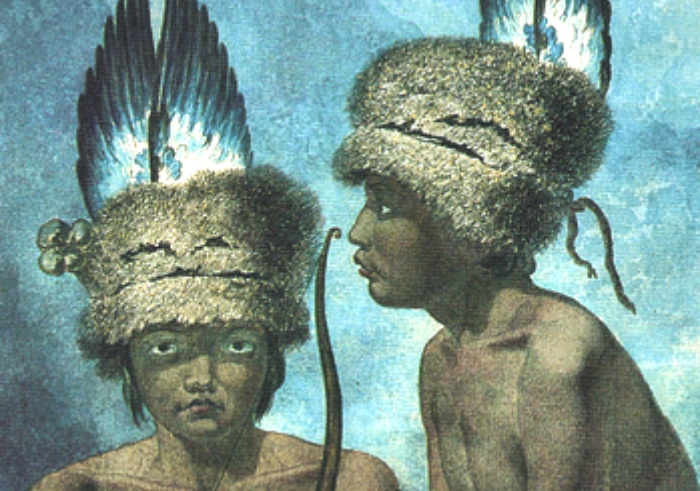

Mikhail Tikhanov, Wikimedia Commons

Mikhail Tikhanov, Wikimedia Commons

A Native American Genocide

Historian Benjamin Madley estimated that between 1846 and 1873 at least 9,400-16,000 California Indians were killed by non-Natives. These tragedies occurred in more than 370 massacres.

This resulted in the Indigenous population of California to fall below 20,000. And it didn’t stop there.

Grace Hudson, Wikimedia Commons

Grace Hudson, Wikimedia Commons

The Horrific Truth

According to the government of California, some 4,500 Native Americans suffered violent deaths between 1849 and 1870. From starvation, disease, and horrendous massacres, the Indigenous population lost 120,000 people as a result of the California Gold Rush.

If that isn’t bad enough, it gets worse.

They Were Opposed To Peace

The overpowering greed that took over America only got worse. Even after countless horrific deaths of Indigenous peoples, California actually opposed 18 treaties signed between tribal leaders and federal agents in 1851.

They were fully in support of gold miners—so much so, that they implemented something absolutely horrific.

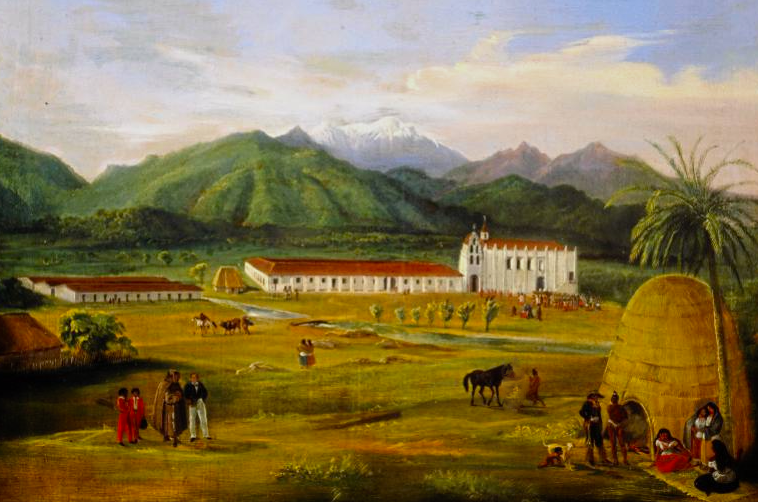

Ferdinand Deppe, Wikimedia Commons

Ferdinand Deppe, Wikimedia Commons

The Introduction Of Death Squads

At this point, the state government kept their eyes on the prize—the gold. And they were willing to do anything to defend it. So, they took some of the cash they were making on this precious, seemingly abundant metal and allocated $1 million toward funding death squads—armed groups tasked specifically with carrying out massacres.

A Battleground Between The Races

Peter Burnett, California's first governor, then declared that California was a “battleground between the races” and that there were only two options toward California Indians: extermination or removal.

He even went so far as to say, “A war of extermination will continue to be waged between the two races until the Indian race becomes extinct".

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Taking Them Hostage Instead

On April 22, 1850, the California Legislature passed the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians. So, instead of killing them, they took them as prisoners instead, and called it “protection".

Settlers were now allowed to capture and use Native people as bonded workers, and adopt Native children—for labor purposes.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Removal From Traditional Lands

The act also facilitated the removal and displacement of Natives in California from their traditional lands, separating at least an entire generation of children and adults from their families, languages, and cultures.

White Man’s Gold

When the dust settled after the horrific Native American genocide, foreigners were on their way out. With discriminatory anti-foreign attacks, laws, and confiscatory taxes (that Whites were not required to pay), the toll on immigrants was severe as well.

Daderot, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Daderot, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

The Devastating Truth

One in 12 forty-niners perished during the prime years of the gold rush. Death and crime rates were exceptionally high, and rates of vigilantism were obscene. While this extraordinary discovery may have brought fame and fortune to many, it devastated even more.

New York Public Library, Picryl

New York Public Library, Picryl

Labor Workers For Hire

After the surface gold disappeared, and foreign miners were retreating home, American miners started working for larger mining companies that invested in technology and equipment to reach gold that was farther below the surface. By the mid-1850s, mining for gold became more of a wage labor job than an individual goal for wealth.

So, what good came of the California Gold Rush?

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

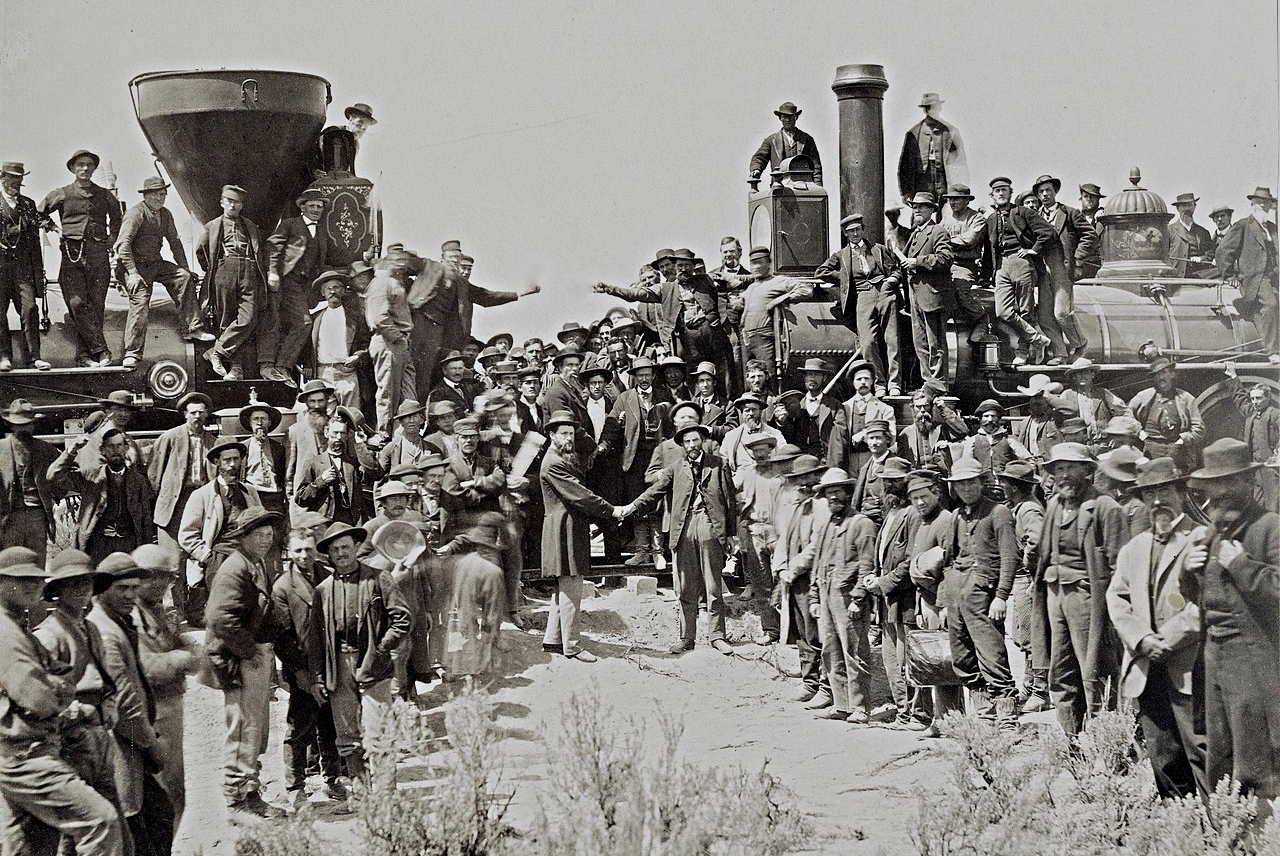

The Statehood Of California

The California Gold Rush is credited for the massive increase in population and infrastructure that qualified California for statehood. The rapid economic growth and prosperity is noted, as well as the building of railroads, churches, banks—all of which would have taken much longer to establish had there not been a gold rush at all.

The profit was also used to fund a groundbreaking project.

George H. Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

George H. Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

The First Transcontinental Railroad

In 1863, the first transcontinental railroad was completed. The line took about six years to complete and was financed in part with gold rush money. It united California with the central and eastern United States, cutting travel time significantly. Trips that would usually take weeks or months could now be accomplished in only days.

But the gold rush also had a bigger impact on people than you may think.

Andrew J. Russell, Wikimedia Commons

Andrew J. Russell, Wikimedia Commons

Cross-Gender Practices

Today, San Francisco is one of the largest and most prominent LGBT communities in the United States. And many believe the gold rush played a part in its beginning.

Because most of the miners and merchants were men, and there were few women around, many of them began to take on cross-gender practices—including how they dress and who they sought comfort in.

Stefano Bianchetti, Getty Images

Stefano Bianchetti, Getty Images

Dancing In Drag

Dance events would often take place where men would dress as women and form new relationships with other men. These acts were encouraged by the social fluidity and population limitations, and are believed to have shaped the beginnings of San Francisco’s prominent queer history.

That’s not the only thing that California became known for, though.

Andre Castaigne, Wikimedia Commons

Andre Castaigne, Wikimedia Commons

Becoming The Golden State

Afterward, California’s name became forever connected with the gold rush, and fast success in the world became known as the “California Dream". The state became known as a place of new beginnings, where great wealth could be found.

California also quickly earned the nickname, the “golden state,” and has continued to attract immigrants from across the globe for decades since.