The Sioux

The term “Sioux” can refer to any ethnic group within the Great Sioux Nation—which comprises tribes from the Great Plains of North America, which is a massive area that covers the central US and parts of western Canada. It’s split into two linguistic groups, the Dakota and Lakota.

The Sioux have a seriously compelling history of fighting fiercely for their rights and their land. Pushed to the brink of extinction multiple times, battling against brutality and injustice—the story of the Sioux isn’t for the faint of heart.

The Očhéthi Šakówiŋ

The name Sioux comes from what the French called the group, “Nadouessioux”, but the Sioux refer to the whole nation as Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, which means “Seven Council Fires”. There are seven nations that make up the Sioux. One is known collectively as the Lakota, while the Eastern Dakota comprises four, and Western Dakota two.

MatthiasKabel, Wikimedia Commons

MatthiasKabel, Wikimedia Commons

All Are Related

One characteristic of the Sioux is their belief in a strong social bond that goes beyond kinship and extends to the natural world, as well as the supernatural. This is represented by the phrase that represents their worldview, Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ, which means “All are related”. This view has has been a guiding force throughout the history of the group, with an emphasis on the bonds of kinship above all. According to one historian, to be Sioux is to be a good relative.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wikimedia Commons

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wikimedia Commons

Early History

The ancestral Sioux originated in the area around the Central Mississippi Valley and later, around Minnesota, where they lived for thousands of years. Around 800 CE, they also began to live in Northwestern Wisconsin, and then, by 1300, they became the Seven Council Fires—but soon after, they found themselves in peril.

![]() U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Rawpixel

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Rawpixel

Trouble Begins

In the 17th century, the Lakota expanded westward into the plains, while the Dakota faced a pressing issue. Conflict with the Iroquois forced them to disperse from where they lived at the mouth of the Mississippi River. Though the nation grew, the Dakota, who made up the eastern part of the nation, had trouble defending that area.

They were plagued by diseases like smallpox and malaria, and faced further threat from the Iroquiois—in the forms of the tribes that were fleeing from them, into Sioux territory. The consequences were brutal, and the Sioux’s eastern population, who lived in the Mississippi valley, declined by one third.

Doane Robinson, Wikimedia Commons

Doane Robinson, Wikimedia Commons

The Fur Trade Era

When Europeans came to the US and began organizing around a fur trade, they attempted to initiate trade with the Sioux—but the reaction was surprising. The emphasis on kinship within the societal structure of the Sioux was so strong, that they found there was no need to do business with people from outside.

As such, the European fur traders began to make attempts to integrate themselves into Sioux society, even marrying into the tribe and forming familial bonds.

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

The French Fur Trade

In this era—the mid 17th century—both the English and the French raced to make contact and initiate agreements with Native tribes in order to dominate the fur trade. By the end of the century, and after years of disregard, the Sioux finally began to trade with the French, receiving European goods in exchange for pelts. But as tribes traded with the English and the French, and then traded amongst themselves, the Sioux found themselves in a difficult position.

Joseph Drayton, Wikimedia Commons

Joseph Drayton, Wikimedia Commons

Intertribal Conflict

The Cree and the Assiniboine tribes had been longtime enemies of the Sioux—and as other tribes, like the Ojibwe, began to trade with them, the Dakota took umbrage. This broke out into violent conflict in 1736, and defeats in battle led to massive losses of territory in Minnesota, as they retreated south along the Mississippi River.

This conflict didn’t just extend to the Ojibwe, either—the Sioux also fought different groups of French traders who worked with the Ojibwe.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

From All Sides

It was as though no matter who the French traded with, it would draw fire from some other tribe—a true “you can’t please every situation,” but with deadly consequences. In 1736, a group of Sioux attacked Jean Baptiste de la Verendreye, taking the lives of the Frenchman and 20 others.

The Europeans struggled to establish some form of peace between the tribes—but ultimately, it was out of their hands, and the French left North America in 1763.

Arthur H. Hider, Wikimedia Commons

Arthur H. Hider, Wikimedia Commons

A Constant Struggle

Just because they left, it didn’t mean the conflict was over. A fierce battle between the Dakota and the Ojibwe ensued in 1770, with the Dakota and their allies, the Meskwawi, suffering catastrophic losses.

At the same time, the Western Dakota and Lakota each established their own trade relationships with other tribes and groups. Even as their ways of life changed, though, the different groups of the Sioux remained united in the priority they placed on community bonds.

Charles St.G. Stanley, Wikimedia Commons

Charles St.G. Stanley, Wikimedia Commons

The First Treaty

In 1805, the Dakota signed a treaty with the US government, where they ceded 100,000 acres of territory around what is now St Paul, Minnesota, in order to establish a trading relationship that also allowed them to pass through and hunt on the land. Other treaties established peace between warring tribes, and ultimately, the first Sioux reservation came into being because of a treaty in 1858. But it wasn’t long before they realized they were dealing with the devil.

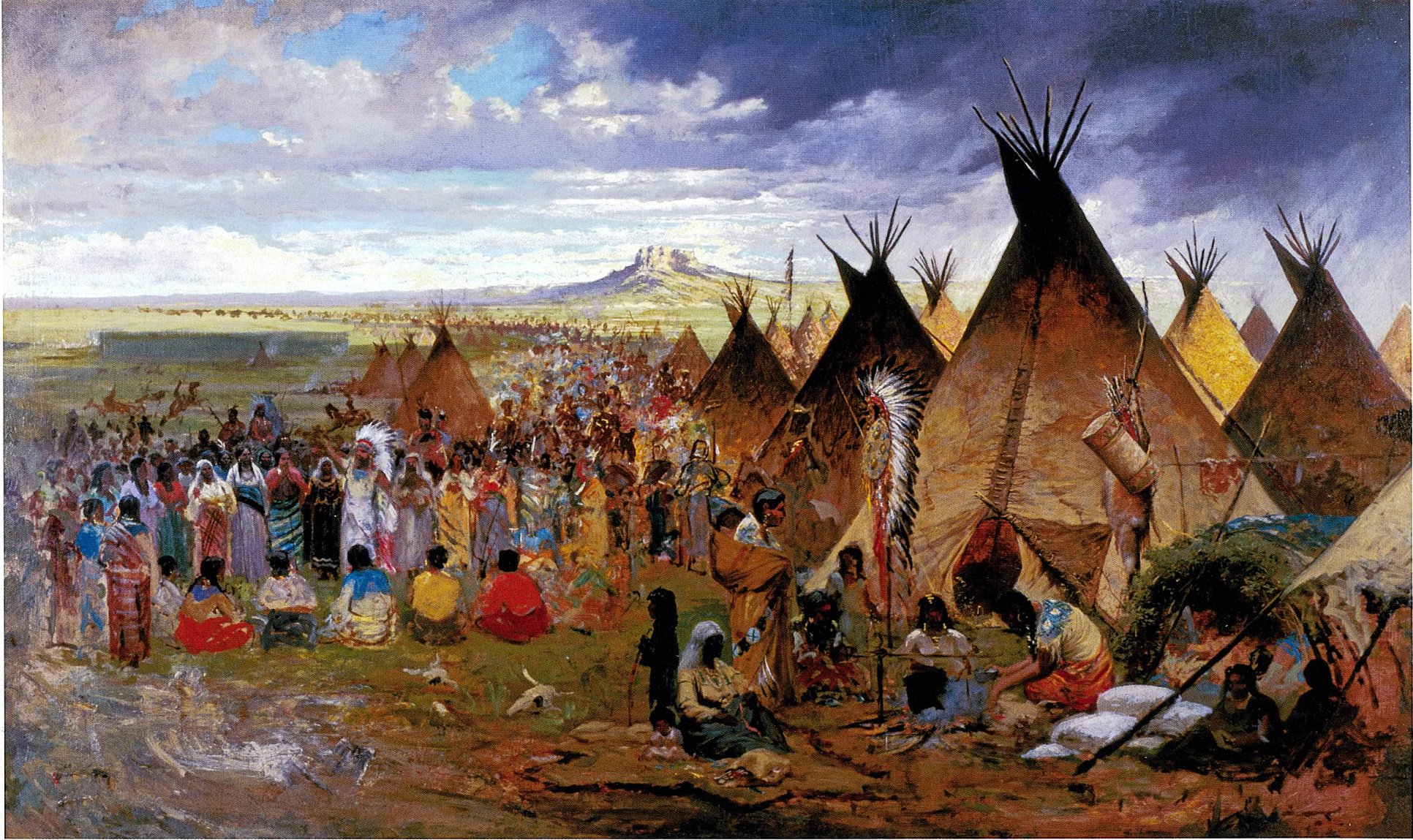

Rosa Bonheur, Wikimedia Commons

Rosa Bonheur, Wikimedia Commons

The Yankton Sioux

The chief of the Yankton Sioux Reservation, Struck by the Ree, remarked that, “The white men are coming in like maggots. It is useless to resist them. They are many more than we are. […] We must accept it, get the best terms we can get and try to adopt their ways”. They knew that they were being crowded out of their lands, and that they were facing an uphill battle against the hordes of settlers.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Pushed Out And Pushed In

The Eastern Dakota faced similar challenges, as they too were boxed in and forced to move to reservations throughout the mid-19th century. They made deals where they ceded land to the government for millions of dollars—but they had no idea what they were in for.

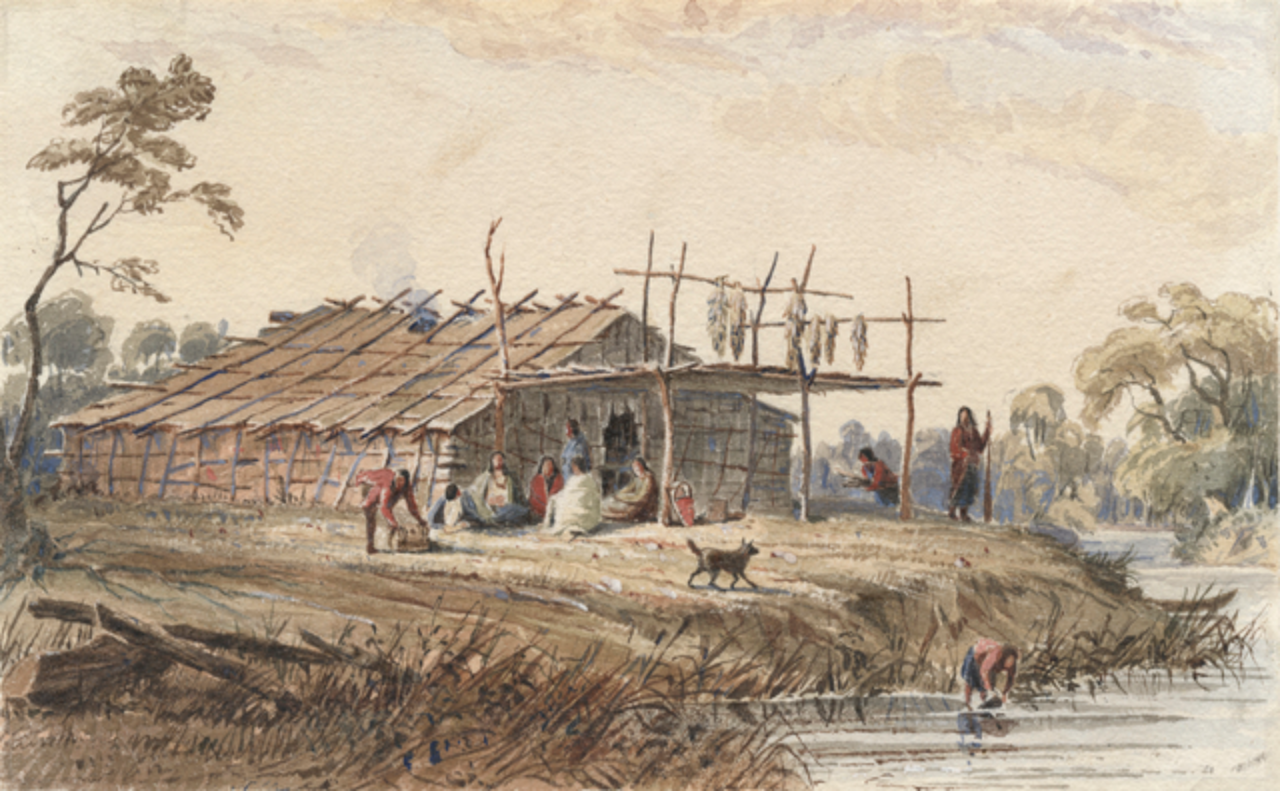

Seth Eastman, Wikimedia Commons

Seth Eastman, Wikimedia Commons

Stabbed In The Back

In one treaty, two Sioux bands gave up 21 million acres of land for $1,665,000—but the US government reneged on their part under the guise of financial stewardship. They paid less than 80% of what they owed, instead meting out small payments from the interest on the deal. Things only got worse from there.

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

The Sioux Way Of Life

Though the government designated certain reservations for the Sioux, they’d often go back on their word and claim they were only temporary solutions—effectively attempting to drive every Sioux from Minnesota, the land they’d lived on for thousands of years. Additionally, they made efforts to change the Sioux lifestyle from a nomadic hunting practices to settled farming.

By 1858, the Dakota had been pushed onto a small strip of land and no longer had access to their traditional hunting grounds. Something had to change.

Jules Tavernier, Wikimedia Commons

Jules Tavernier, Wikimedia Commons

The Dakota War of 1862

When the government failed to make their payment to the Dakota between 1861 and 1862, they blamed failed crops and a harsh winter. It took until August for the government to finally pay what they owed the Dakota—but it was too late. The Dakota began to attack settler communities along the Minnesota River.

Though it was reported to be the entire Dakota nation, it was actually a small faction—but nonetheless, they made an impact.

Biersach, Paul C., Wikimedia Commons

Biersach, Paul C., Wikimedia Commons

Karmic Retribution

As the US government tried to starve the Dakota over the winter from 1861 to 1862, one trader, Andrew Myrick, remarked “If they're hungry, let them eat grass”. He’d come to eat those words…quite literally. Later that year, his lifeless body was found by a group of settlers—and his mouth had been stuffed with grass.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

A Miscarriage of Justice

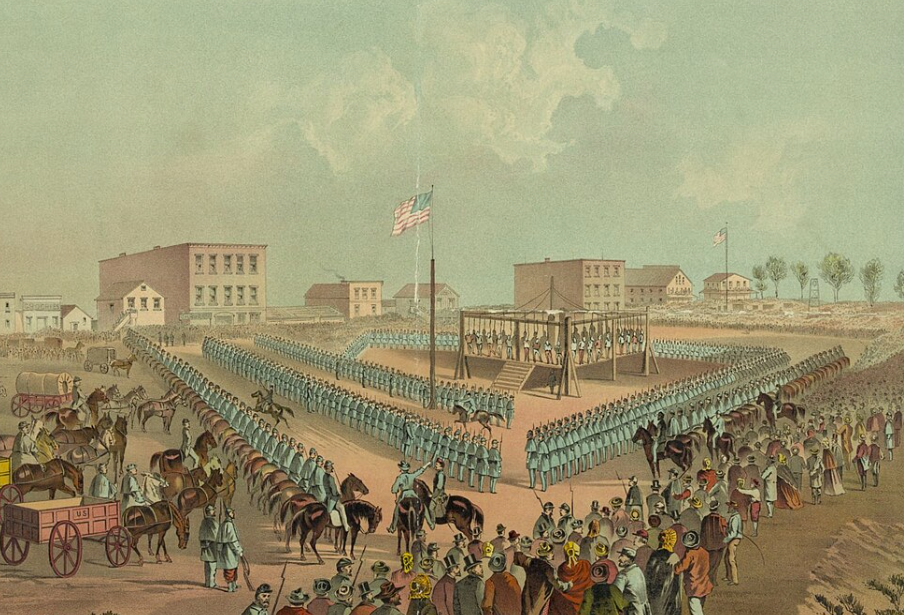

After just over a month of battle, members of the warring Dakota faction either surrendered or retreated. A military tribunal put hundreds of those men on trial for atrocities committed during the conflict and quickly sentenced them to hanging—barring them from having representation and in any many cases, finding them guilty in less than five minutes. But it didn’t end there.

President Abraham Lincoln commuted the sentences of 284 of the men. Unfortunately, that still left 38 on the hook—and their hangings became the largest mass-execution in US history, on US soil.

US Federal Government, Wikimedia Commons

US Federal Government, Wikimedia Commons

No Easy Way Out

Sadly, Lincoln’s attempt to lessen the requital upon the Sioux didn’t exactly work out as he’d intended. Most of the remaining 284 men were imprisoned, and among those men, many passed on during their confinement. Additionally, the US government retaliated against the remaining Dakota by expelling them from the remaining lands they held. Most left for the Dakota territory or for Canada.

Benjamin Franklin Upton, Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin Franklin Upton, Wikimedia Commons

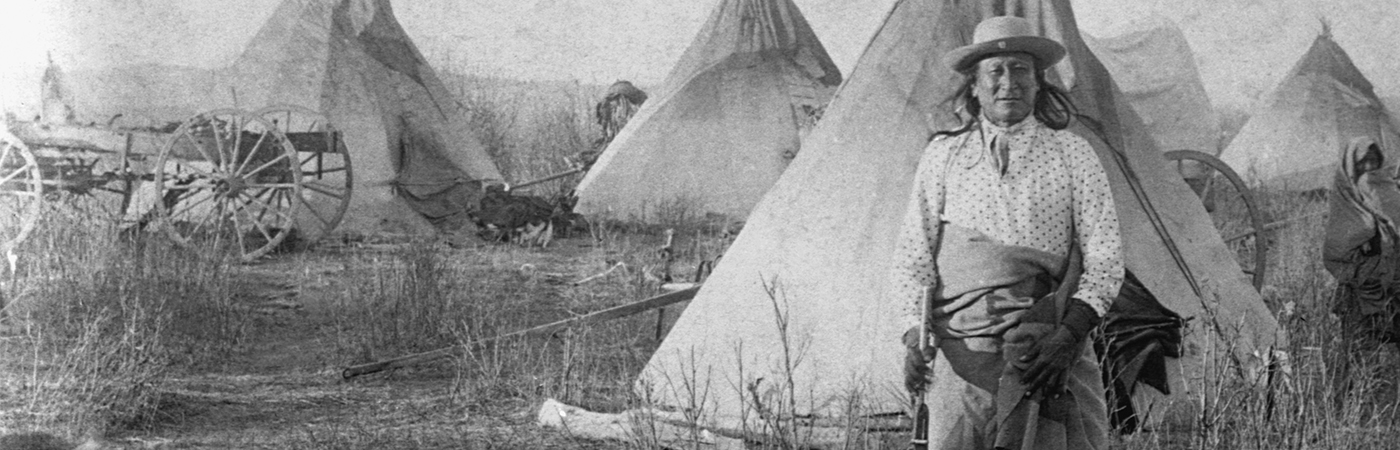

The Lakota

On the other side of things, the Lakota people lived relatively peacefully throughout all the upheaval that the Dakota suffered. They began to use horses to hunt buffalo, and their lifestyle and culture centered around this practice. Though the tribes were scattered, they’d gather in a large group in the summer so that the leaders could meet and plan. Then, when it came time to hunt in the fall and prepare for the winter, they would split up again.

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

Lakota Territory

As the Dakota’s territory was ceded to the unscrupulous settlers, the Lakota were actually able to expand their territory, and they came into contact with other tribes—in some cases, making alliances, and in others, battling for land. They were mostly victorious in these battles, as the smaller tribes had been weakened by disease. By the middle of the 19th century, the Lakota were the most powerful tribe on the Plains.

Personal collection, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Personal collection, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Black Hills

The Sioux were one of many groups who signed the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, where swathes of land were assigned to the group of tribes, and peace was brokered between them. The Sioux Treaty Lands that came out of this were centered around the Black Hills, including a parcel of land that intersected Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Wyoming.

Conflict erupted almost immediately.

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

Broken Promises

The Lakota had a long-running conflict with the Crow, and although both were supposed to keep the peace as part of the treaty, the Lakota attacked the Crow not long afterward. On top of that, the area was soon beset by wannabe miners during a gold rush, and the government didn’t hold up their end of the bargain to keep them off Sioux land. Soon, they were mining on native land, leading to even more conflict.

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

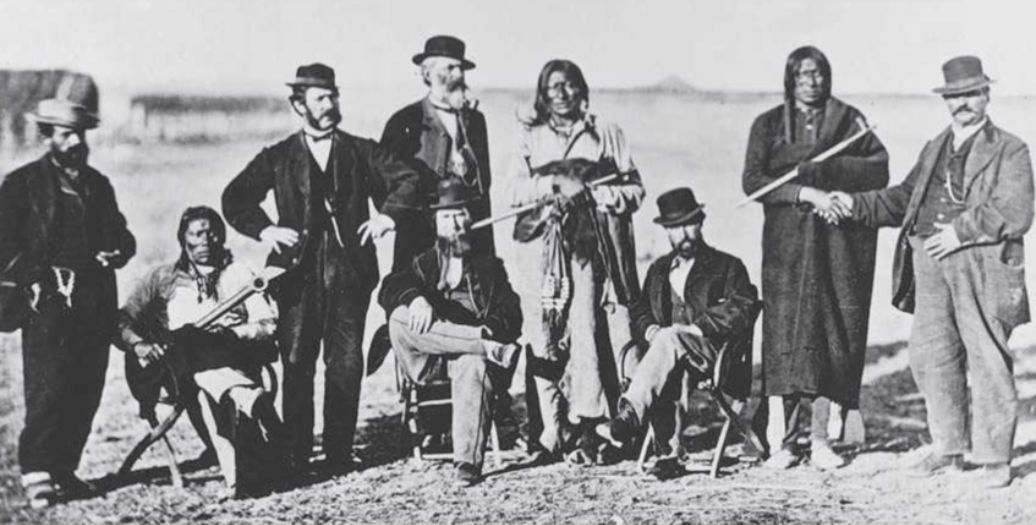

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868

Another attempt at peace was brokered with another treaty—this one even more aggressive in its attempts to get the Sioux to conform to the settler’s way of life. And once again, the US immediately reneged on their part, allowing settlers and gold rushes—and General George Armstrong Custer—onto the Sioux land.

Over the years that followed, the US illegally took back that land. It not only led to conflict and chaos—the aftermath of the theft is something that still reverberates to this day.

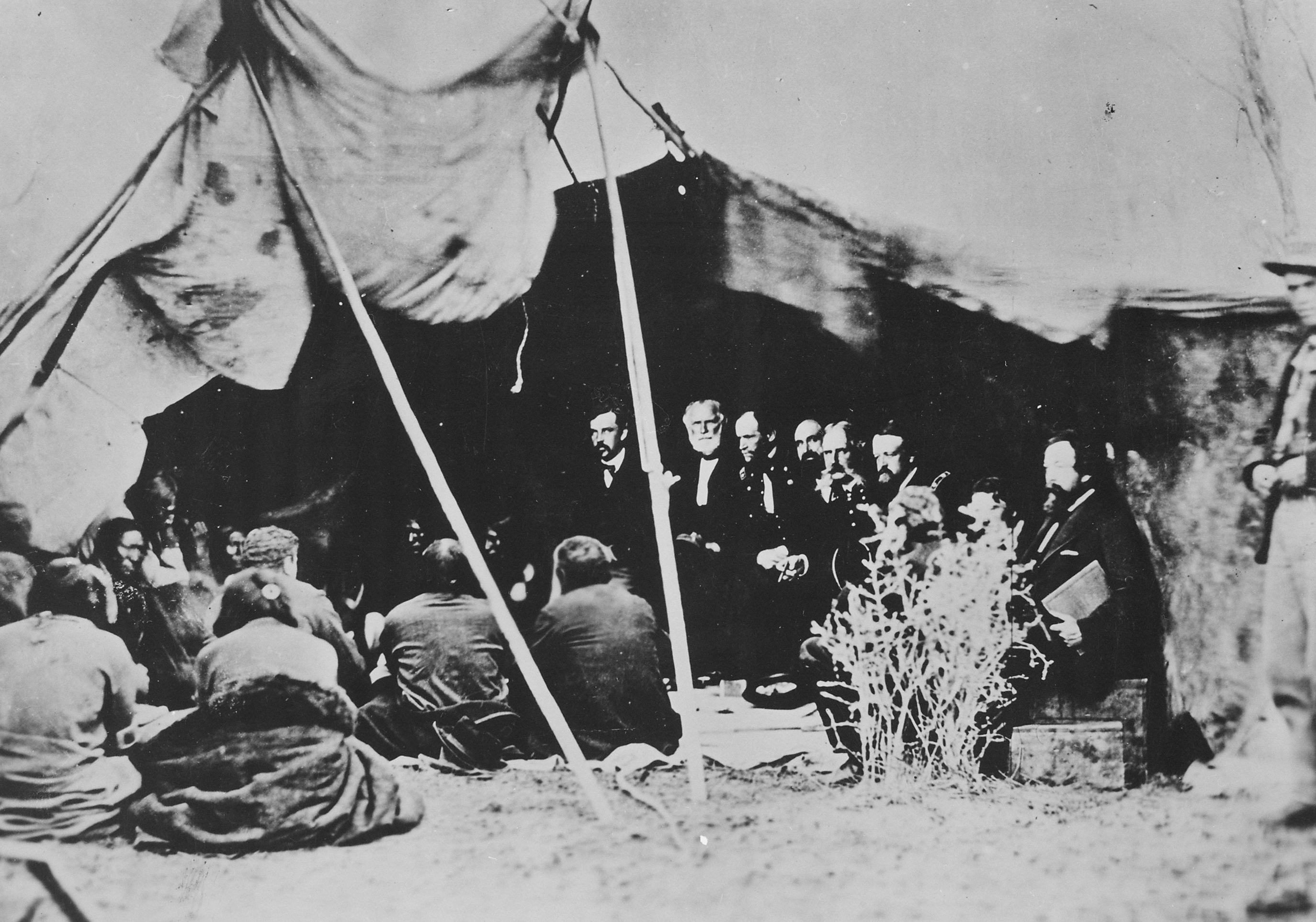

Alexander Gardner (1821 – 1882), Wikimedia Commons

Alexander Gardner (1821 – 1882), Wikimedia Commons

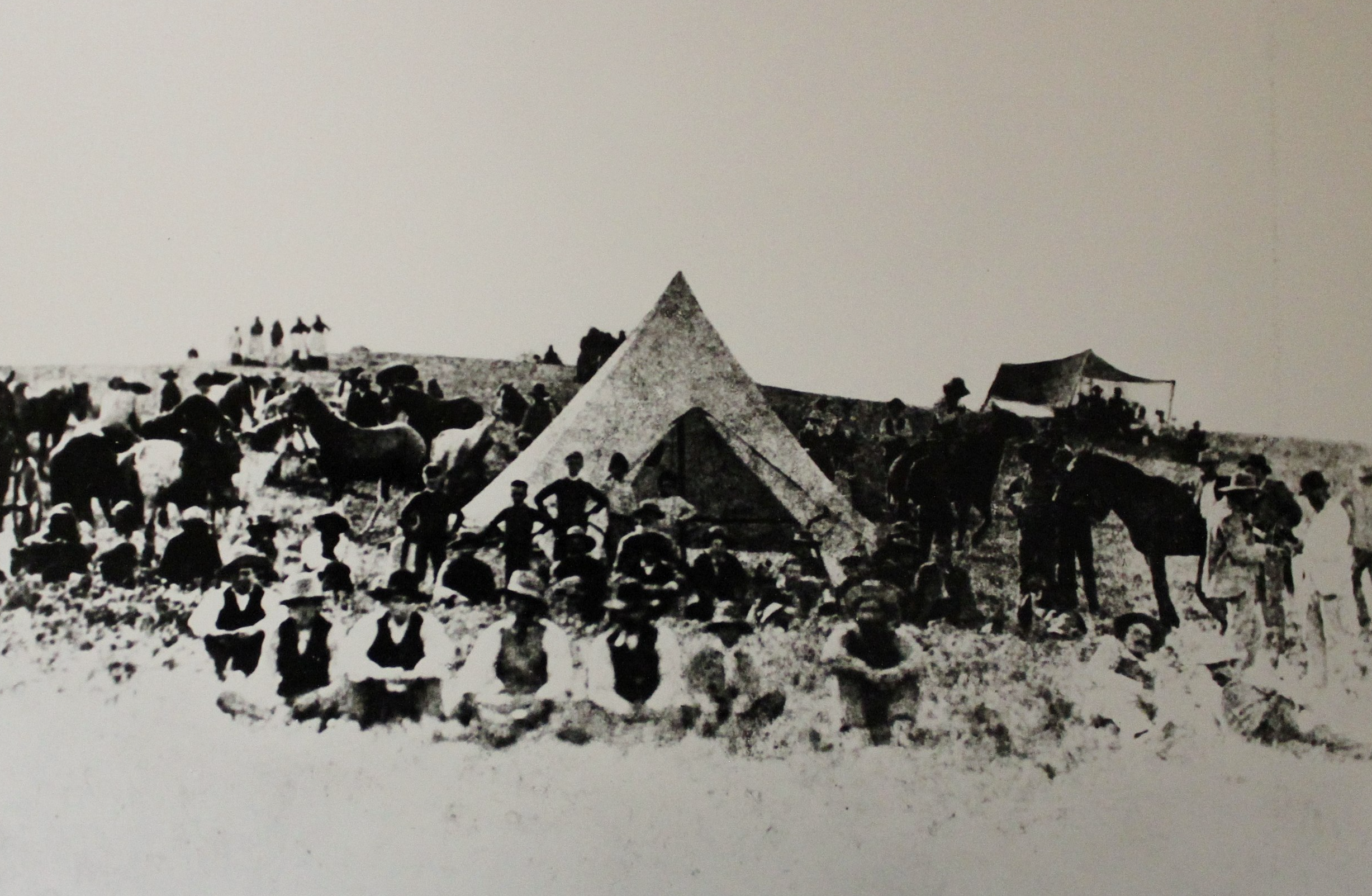

The Great Sioux War

The series of battles and conflicts that took place before and after these disastrous treaties became known as the Sioux Wars. One of the most remarkable battles within these was the Battle of Little Bighorn, AKA Custer’s Last Stand. The Lakota worked with the Cheyenne and the Arapaho in a decisive defeat against the US. Many notable figures including Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and Chief Gall participated.

Unfortunately, the Sioux needed a lot more than one victory to win again the government, who wanted the Black Hills and all the gold underneath them.

Charles St. G. Stanley, Wikimedia Commons

Charles St. G. Stanley, Wikimedia Commons

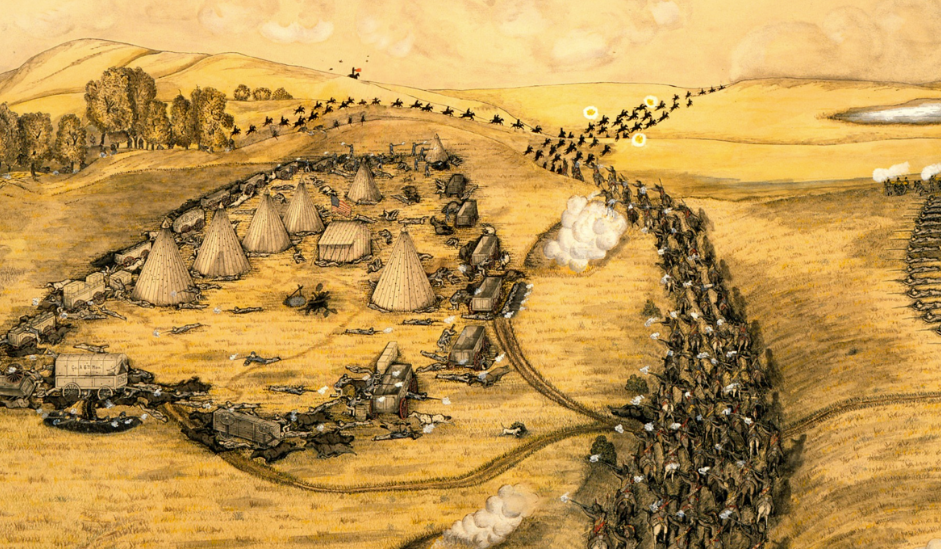

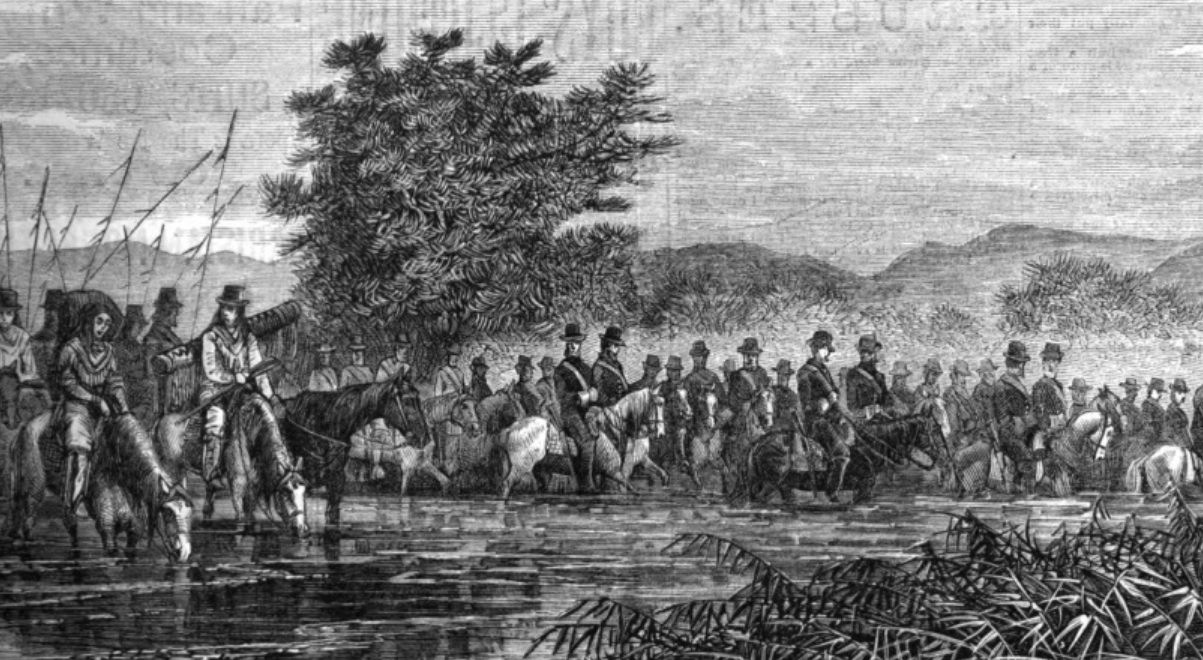

The Massacre At Wounded Knee

The Lakota had vanquished General Custer and scores of his men in the 7th Cavalry Regiment—but the survivors came back for revenge, perpetrating one of the most horrific atrocities in US history. The regiment attempted to move the Lakota from their land to Nebraska, only to kill 150 of them in cold blood, women and children among them. About the same amount of Lakota fled, only to face freezing conditions and hypothermia.

Though the US government looked upon this incident proudly, in recent years, Lakota representatives have asked for the medals of honor that were given to soldiers who participated at Wounded Knee be rescinded.

Amédée Forestier , Wikimedia Commons

Amédée Forestier , Wikimedia Commons

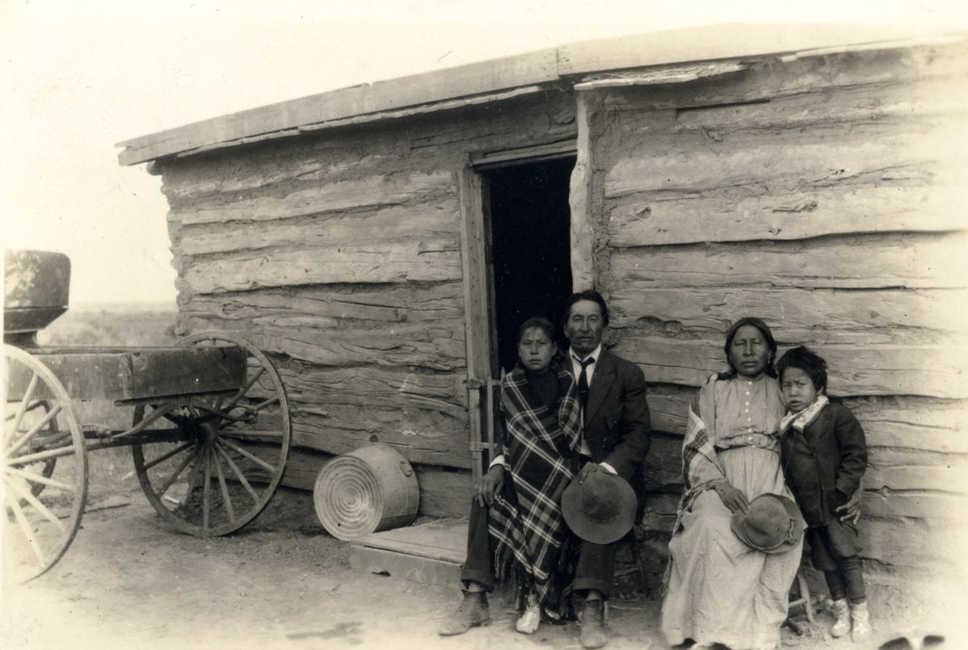

Assimilation Era

Having been continuously scammed out of land by bogus treaties, and driven to the brink of extinction by the US government, the surviving Dakota and Lakota were spread out onto reservations, with even more land clawed back from those in the years that followed. Additionally, they were required by law to give up their traditional ways of self-governance, and instead forced to participate in a capitalist relationship with regards to property.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

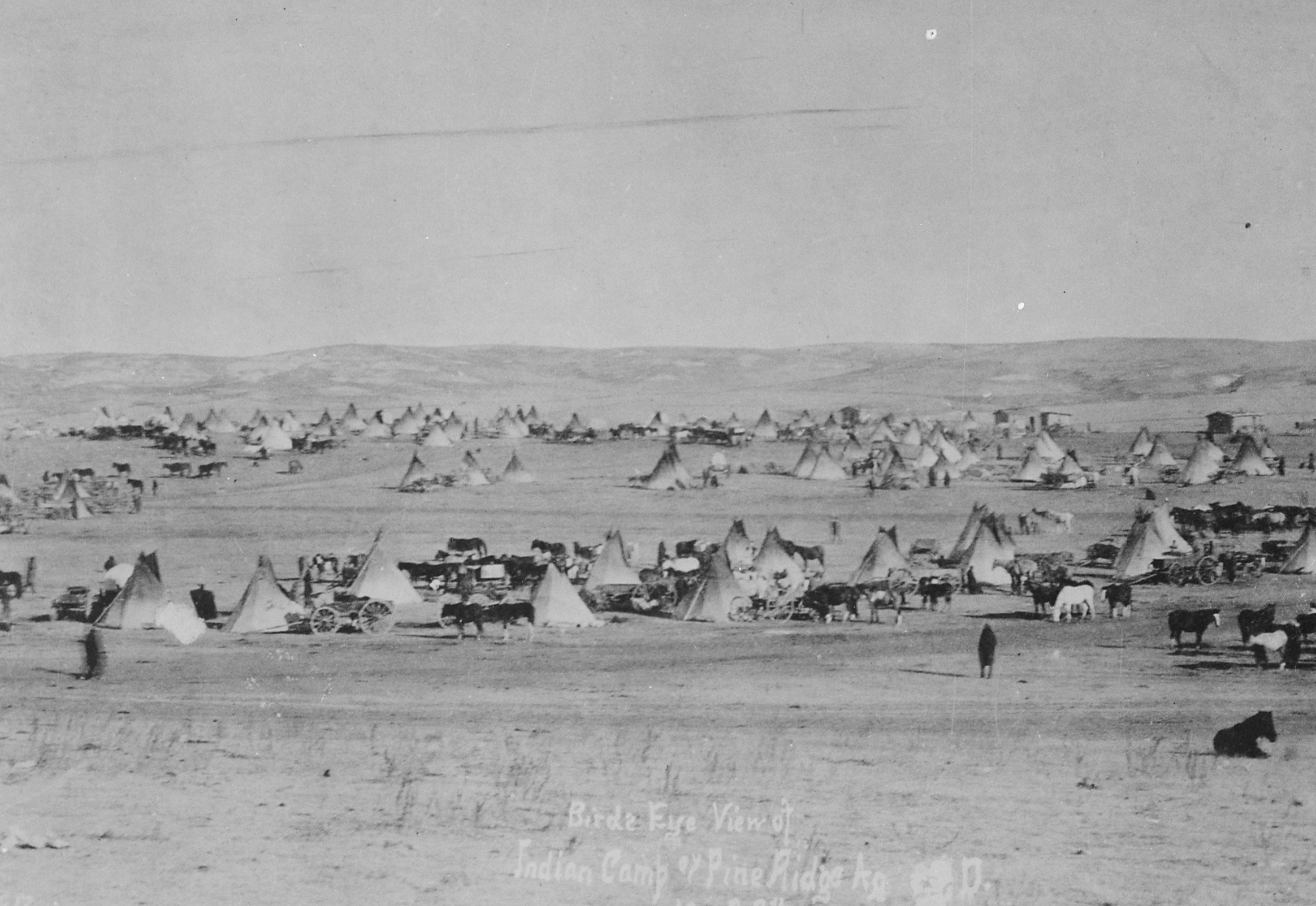

Partition

Despite fierce opposition from leaders like Chief Gall and Sitting Bull, the Great Sioux Reservation was split into five reservations: Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Lower Brule, Rosebud, and Pine Ridge—with the government taking 9 million acres away in the process.

David F. Barry, Wikimedia Commons

David F. Barry, Wikimedia Commons

“Re-Education”

Additionally, the Dawes Act decreed certain standards of behavior for Native Americans, who were expected to adhere to “Euro-American norms of conduct” instead of the ways of life that they’d known for centuries. As a result, many children were forced to go to boarding schools in an attempt to further assimilate the younger generations.

For a culture united by bonds of kinship, this forced separation from family and traditional education destroyed their way of life.

John Grabill, Wikimedia Commons

John Grabill, Wikimedia Commons

Walking It Back

And then, after centuries spent trying to destroy the way of life not only for the Sioux but also every native tribe, the US government appeared to make an attempt to walk it all back—or did they? Though the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 appeared to give more land rights to tribes, many resisted it out of a sense of well-earned mistrust.

At the same time, the government seized thousands of acres of land during the construction of the Oahe Dam. To add insult to injury, the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 encouraged tribe members to leave reservations in favor of cities, which had a devastating effect on both those who left and those who stayed.

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

The Wounded Knee Incident

Conflict within tribes with regards to these acts and potential corruption of tribal leaders led a faction from the American Indian Movement (AIM), to enter the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1973. For 71 days, they occupied the town, as the FBI and the US Marshals attempted to root them out. In April, as the violence intensified, the Oglala Lakota called for an end to the occupation.

The Aftermath

When all was said and done, the authorities detained 1,200 Native Americans who had participated in the occupation. Despite this, the incident garnered national attention for the plight of natives in the US and the various atrocities they’d been victims of.

$1 Billion

In 1980, the Supreme Court tried the case United States v Sioux Nation of Indians, which centered on the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868—one of many that the US failed to fulfill their responsibilities for. Ultimately, it ruled that the Black Hills, which had been covered under the treaty, had been wrongfully stolen by the US government, and offered the Sioux $1 billion in compensation and interest. Their reaction was ice cold.

Instead of accepting the settlement, the Sioux had demanded a complete return of the land that was stolen from them.

Runner1928, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Runner1928, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Nightmare Continues

The closures of the boarding schools that popped up in the wake of the Dawes Act in 1978 seemed like it would be a chance for a fresh start for the Sioux people, to reunite their families and have the chance the educate them in the manner they chose—but sadly, due to systemic prejudice, the nightmare continued. When the schools closed, children were instead removed from their families through the Department of Social Services.

What’s more is that, although they were supposed to uphold the Indian Child Welfare Act, which decreed that children should be placed with relatives or within their tribe, the South Dakota Department of Social Services failed to abide by those rules. In recent years, activists have sought to shed light on and fix this continuing injustice.

Pierre Jean Durieu, Shutterstock

Pierre Jean Durieu, Shutterstock

Standing Rock

The Sioux also continue to fight for their land, and became the drivers of the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline, which is meant to pass under the Missouri River, just north of the Standing Rock Sioux reservation—with the lethal potential to contaminate that important source of water. Sadly, though the pipeline is in operation today, continued protests and legal actions seek to stop it and its potential for environmental catastrophe.

U.S. Department of the Interior, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Department of the Interior, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Continuing The Fight

During the mid-18th century, some estimates put the Sioux population at about 150,000. Through the many conflicts, atrocities, and cultural decimation in the decades that followed, the population shrank, reaching a low of 23,318 people in 1910. In the past 100 years, the Sioux population has made a comeback, with 207, 456 counted in the 2020 census.

Pierre Jean Durieu, Shutterstock

Pierre Jean Durieu, Shutterstock

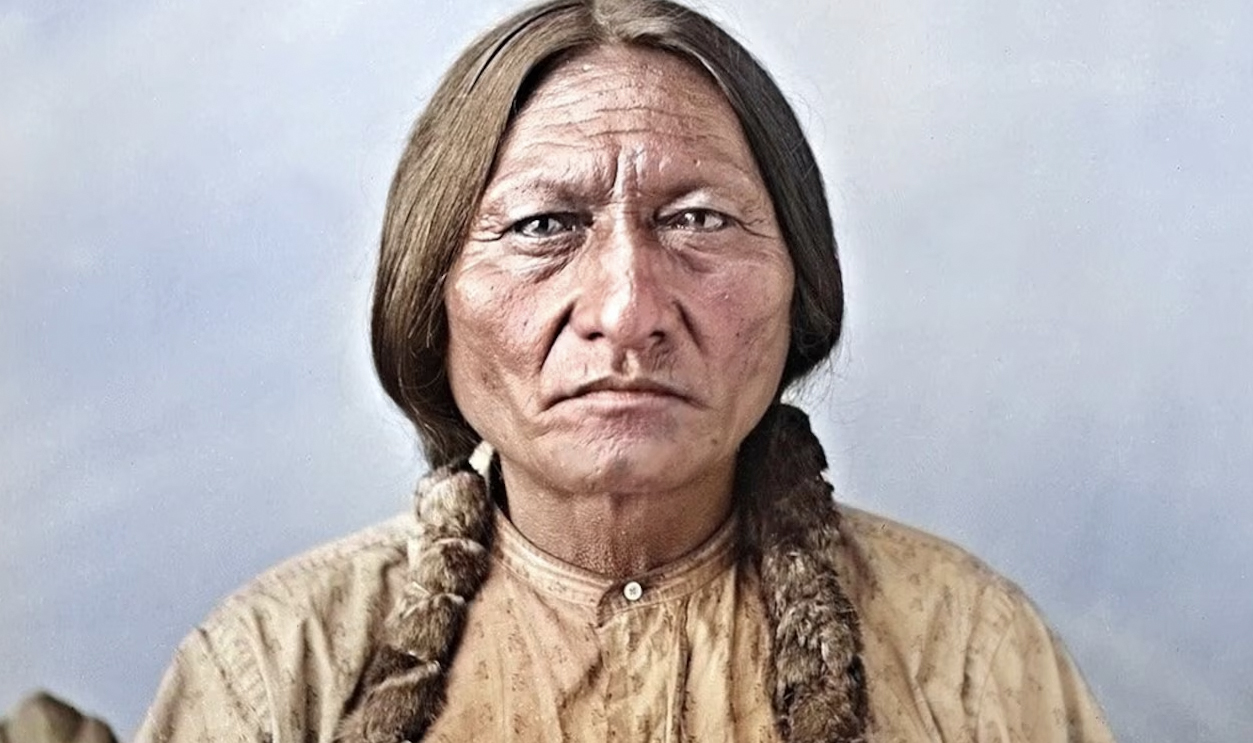

Sitting Bull

Perhaps the most notable figure in Sioux history is Sitting Bull, the 19th century Lakota leader who helped guide resistance against the US government and its policies. Notably, before the Battle of Little Bighorn, he reported having a vision that predicted the victory of the Lakota and their allies against General Custer and his men.

Julian Scott, Wikimedia Commons

Julian Scott, Wikimedia Commons

Too Powerful To Stop

The fear that this victory and Sitting Bull’s leadership inspired in the US forces was immediate. They sent scores of men to attempt to stomp out the resistance, but Sitting Bull evaded capture for years. While he eventually surrendered, he was regarded as such a potentially radical influence that the US government ordered his arrest.

Sadly, in the struggle that ensued, he was shot and perished from his wounds. Regardless, he remains one of the most influential figures in Sioux history.