America's Last Wild Man

In 1911, just before sunset, a 50-year-old Native American man walked over to a rural slaughterhouse in Oroville, California in the midst of severe forest fires in the area. He was starving, alone, and utterly unknown to the locals.

But they were about to learn his incredible and tragic story.

A Cold Reception

After neighbors and nearby workers noticed the man, the Sheriff arrived and told the men to handcuff the lone stranger. When they did so, he just smiled and allowed it.

Soon, word got around about this "wild man."

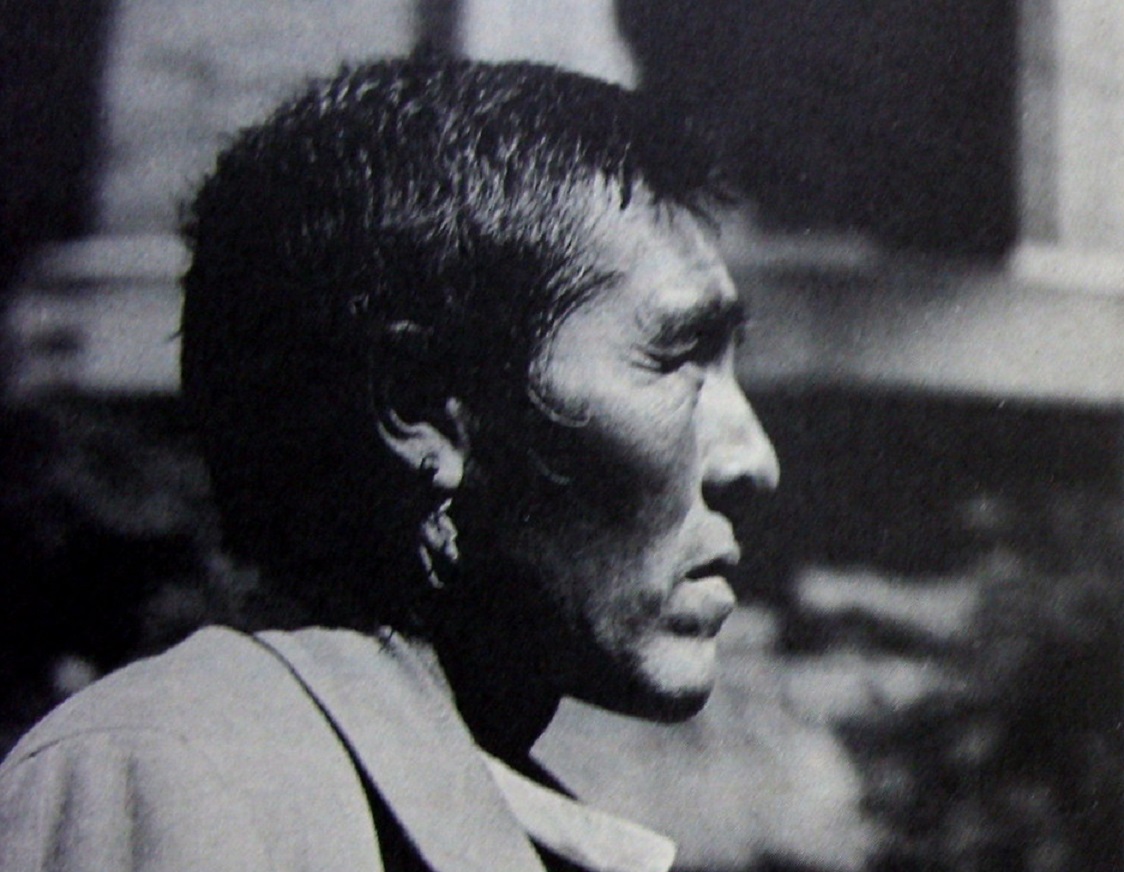

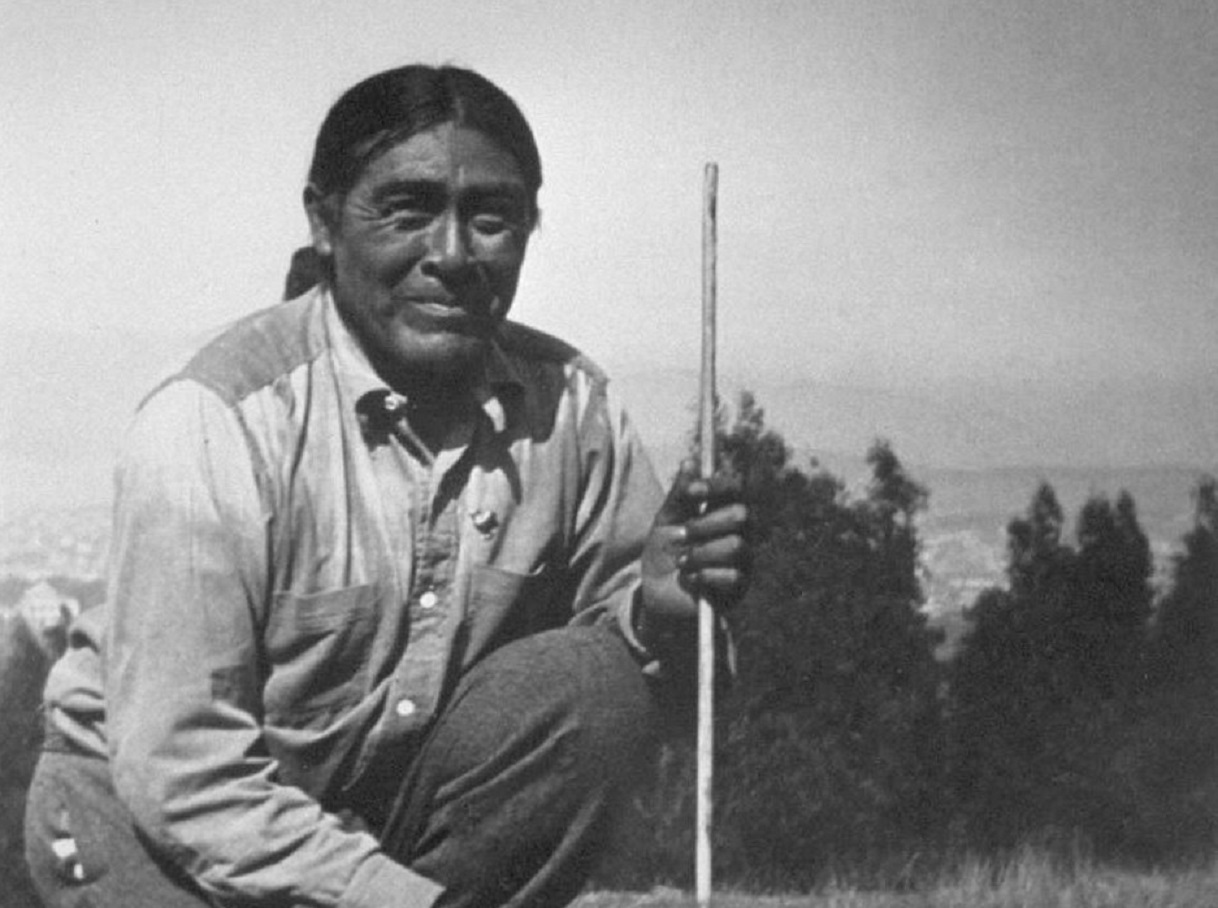

Online Archive of California, Wikimedia Commons

Online Archive of California, Wikimedia Commons

Interest In His Story

Popular interest grew about the man, so much so that the University of California, Berkeley took notice. Their anthropology professors believed his history, whatever it was, would be valuable to them. So they took him in and began questioning him.

His Origins

The professors soon learned that the man belonged to the Native American Yahi people, who traditionally lived in present-day California. But this fact was steeped in tragedy.

The Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush of the mid 1800s had severely depleted the Yahi population through Western diseases, resource damage, and outright violence. And then it got much worse for them.

The End Of His Kind

In 1865, more destruction came for the Yahi people. That year, the United States Army battled the Indigenous people of California in the Three Knolls Massacre, which more than decimated the already tiny Yahi population.

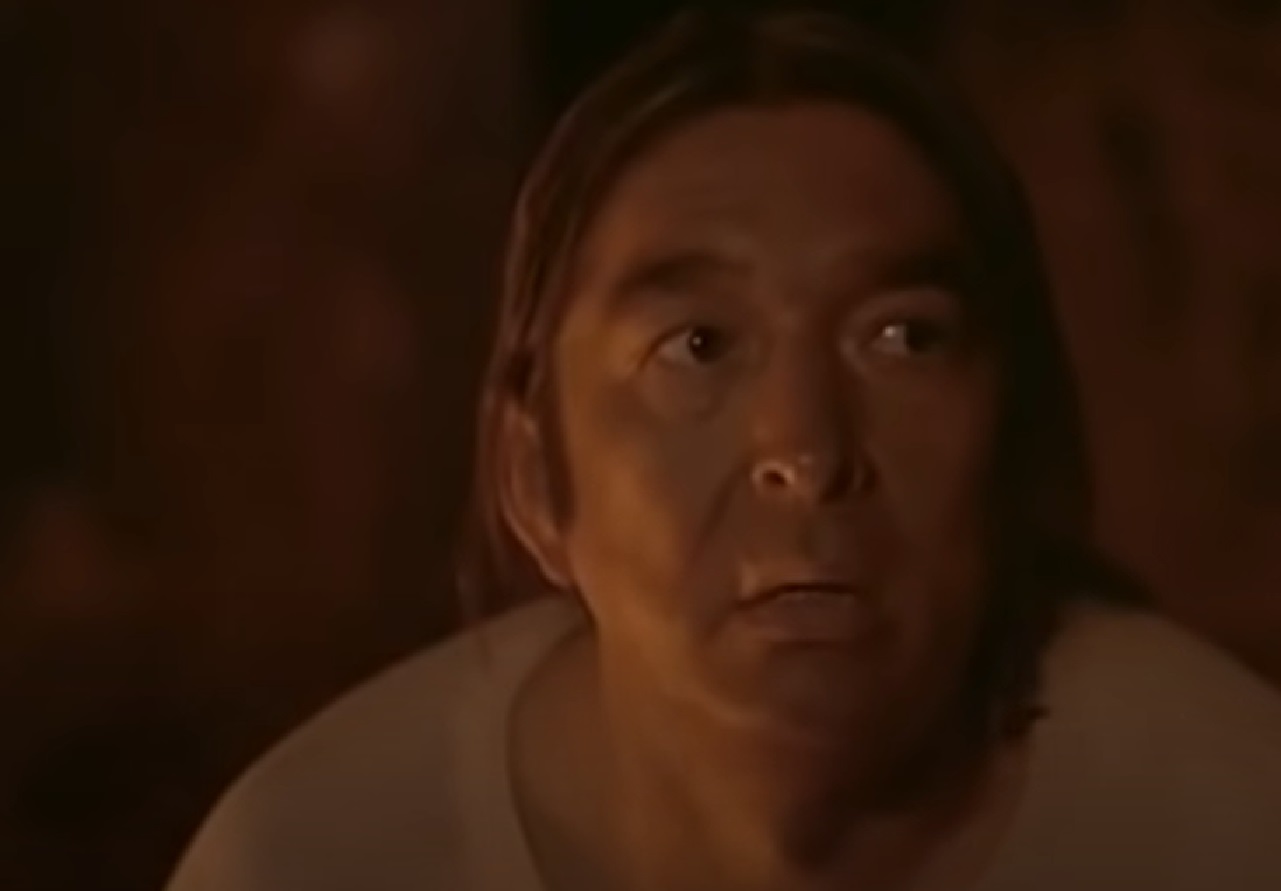

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Escape

After the massacre, 33 Yahi people managed to flee...right into more mortal danger. After their escape, ranchers killed another half of the survivors. At that point, the lone "wild man" and his family were an endangered species.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Unknown Man

Eventually, researchers asked the man what they should call him, but they probably weren't prepared for his tragic response. In Yahi culture, no one could speak their name unless another Yahi formally introduced him.

Thus, the man said about his name: "I have none, because there were no people to name me."

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

His Name

Faced with this, the anthropologist Alfred Kroeber worked around the problem by naming the man "Ishi," which means "Man" in Yana, the language native to the Yahi. But even after this violence, more loss was to come for Ishi.

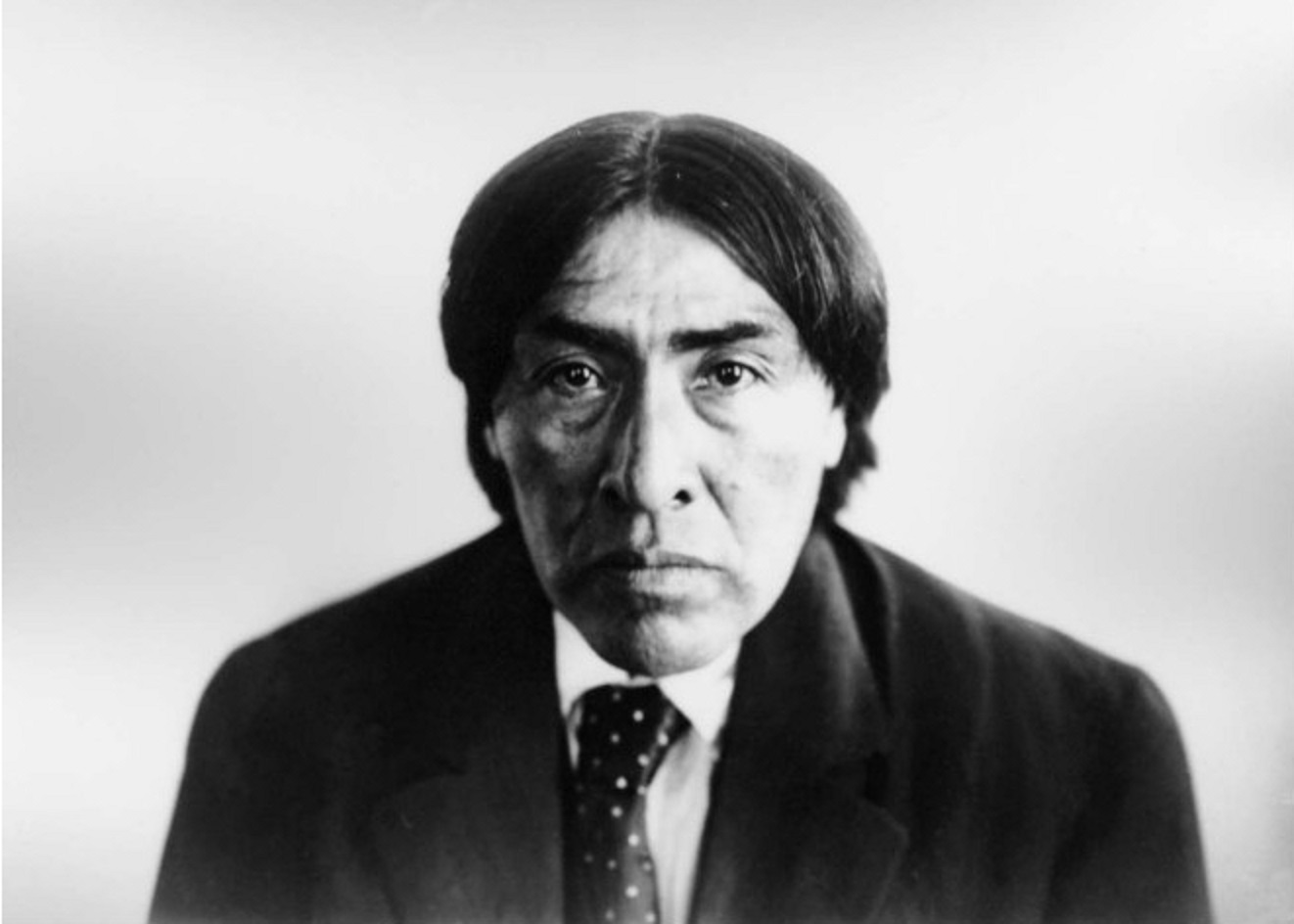

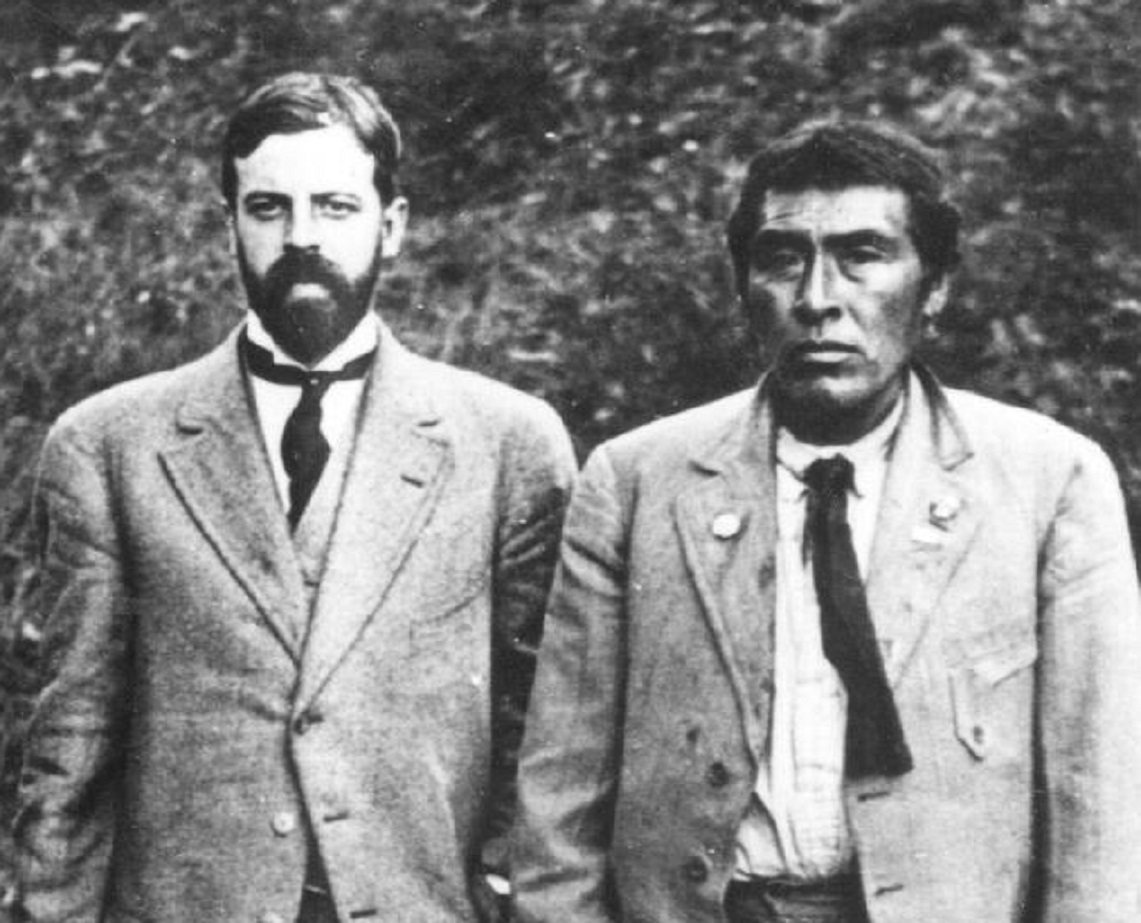

http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt5b69n7tp/, Wikimedia Commons

http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt5b69n7tp/, Wikimedia Commons

Into Hiding

Although "Ishi" and his family had still somehow survived all these trials, they knew now that it was them against the world. As a result, they went into hiding...for the next four decades.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Wiped Off The Face Of The Earth

In the wake of the Three Knots Massacre and the ensuing violence from ranchers, most people had believed that the Yahi tribe was completely extinct—but they did get one glimpse of Ishi in the decades before he reemerged.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

A Secret Place

In 1908, some surveyors actually stumbled across Ishi and his family. The surveyors found a camp that housed two men, a middle-aged woman, and an elderly woman. These people were Ishi, as well as his uncle and mother, while the other woman might have been his wife.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

More Tragedy

Instead of either helping Ishi's family or leaving them alone, the surveyors decided to inflict more cruelty on them. While the younger members fled and the elderly woman—too old and crippled to run—hid herself, the surveyors raided the camp for its fur, weapons, and nets.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Where Did They Go?

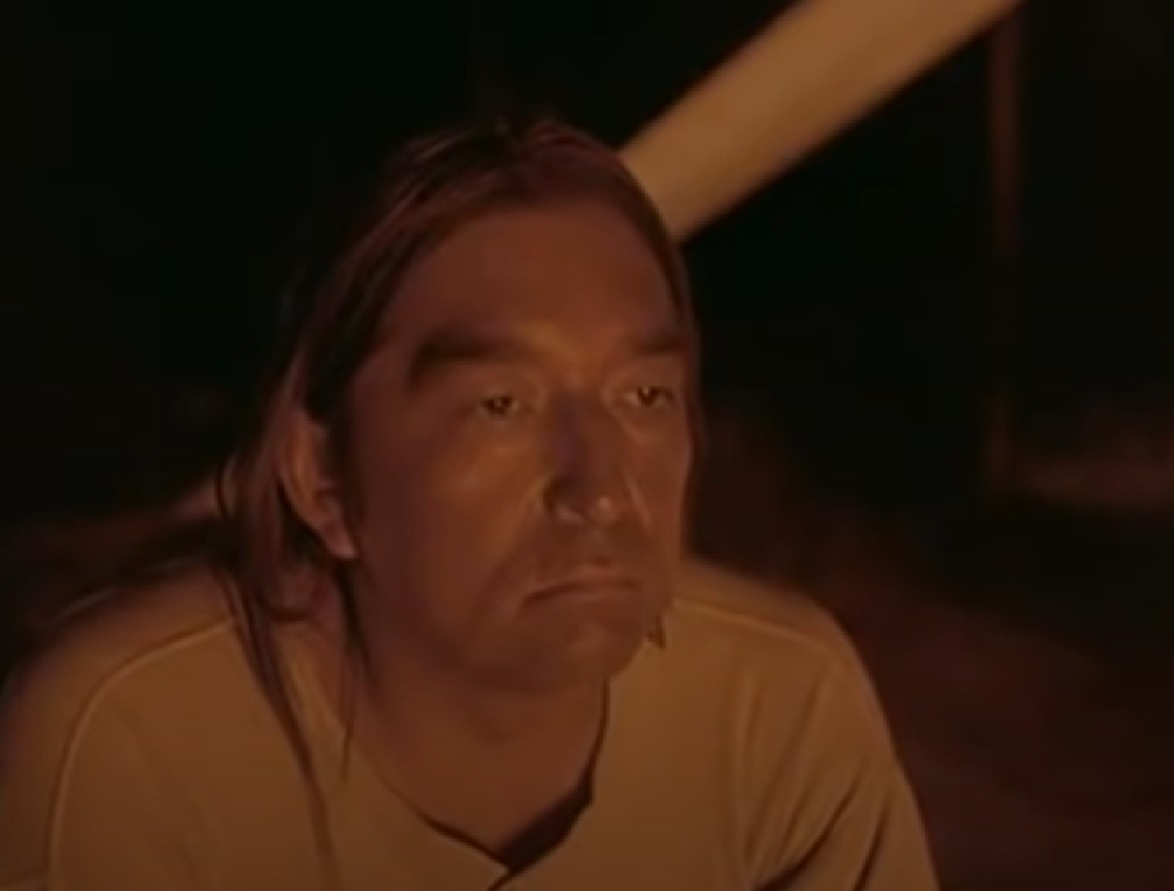

Ishi went into the outside world just three years after this chance encounter, yet none of his family was with him. As Ishi related to the outsiders through mime, his family had all perished—his uncle and mother by drowning.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

The Western World

Ishi's time with the anthropologists at Berkeley was certainly less violent than his other interactions with settlers, but it wasn't ideal. He spent most of his time being studied by them as a kind of specimen.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

His Culture

Through extensive and regular interviews, the Berkeley professors tried to get Ishi to tell them about the elusive Yahi culture. They confirmed through him that the Yahi lived in small, egalitarian groups and had no central governmental authority.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

His People

Overall, the Yahi people were reclusive. However, although they possessed no firearms, they passionately defended the mountain canyons that they lived in.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Material Talents

Ishi also demonstrated his skill making various items in the Yahi tradition. In particular, he was the last known Native manufacturer of stone arrowheads.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Losing His Cultural Memory

Sadly, however, although Ishi taught the professors everything he could about Yahi families, naming conventions, and ceremonies, at the time he was growing up much of the Yahi culture was already lost to settler violence. Thus, his knowledge was limited.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

His Home

When the university professors first "brought" Ishi back with them, they treated him as an artifact. In fact, he made his home in the Affiliated Colleges Museum, a campus building.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

His Work

While the professors studied Ishi, they also put him to work as a janitor.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

His Friends

Although Ishi was frequently in contact with the Berkeley professors, he was perhaps closest with a UCSF professor of medicine, Saxton T. Pope, during his time with the colonizers.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Passing Down His Knowledge

Ishi taught his friend Saxton Pope how to make bows and arrows as the Yahi did, and the pair often hunted together.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Hunting Style

There are multiple ways to draw and release a bow. Ishi, in accordance with Yahi tradition, used "thumb draw and release" on his short bows.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Celebrity

After going to Berkeley, Ishi became something of a celebrity. At one point, the professors took him to the Orpheum Opera House to see Lily Lena, the famous "London Songbird." While there, Lena gave him a piece of gum as a souvenir.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Mapping Out His Land

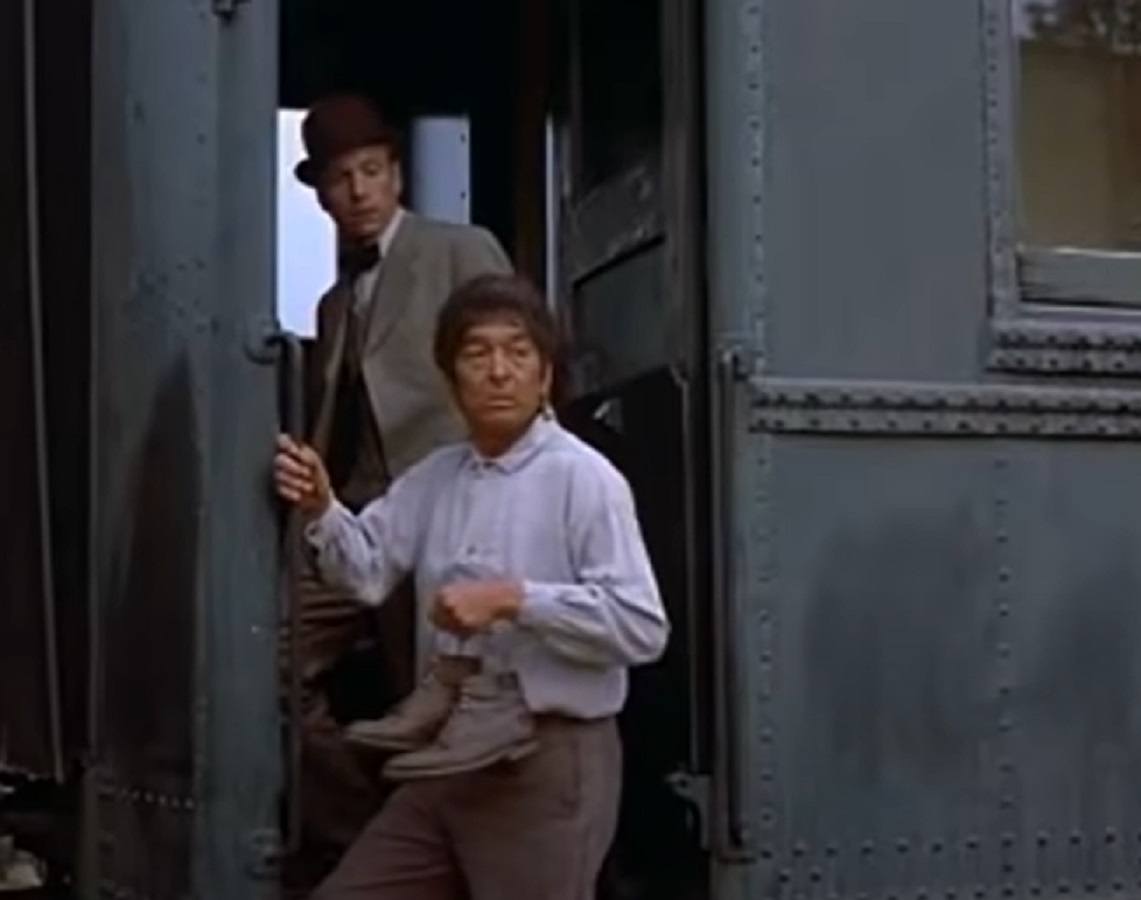

The professors also brought Ishi on a train trip through the Deer Creek area of Tehama country, hoping he could help them research and map out the area for the university.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

On Film

Film technology was just beginning at the time, and in 1915 Ishi was filmed alongside the actress Grace Darling for a news pictorial.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

On Record

Researchers also made sure to preserve as much of Ishi's language as they possibly could. In 1915, they recorded him speaking his native Yana language, and the tapes were reviewed by linguist Edward Sapir.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

A Piece Of Ishi

The wax cylinders that contained Ishi's speaking voice were eventually recovered and translated to a new, more durable medium. The recordings still exist today.

Saxton T. Pope, Wikimedia Commons

Saxton T. Pope, Wikimedia Commons

Illnesses

Because Ishi never got immunity against Western diseases, he was frequently sick while at the university. When this happened, his friend Saxton T. Pope would often treat him.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Time Running Out

Ishi's constant illnesses meant that in the end, his time at Berkeley was incredibly short. He actually only lived five years after first emerging from isolation.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

His Death

On March 25, 1916, Ishi finally lost a battle with tuberculosis. At the time, he was only 55 or 56 years old.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

His Last Words

According to reports, Ishi's last words were "You stay. I go."

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

The Aftermath

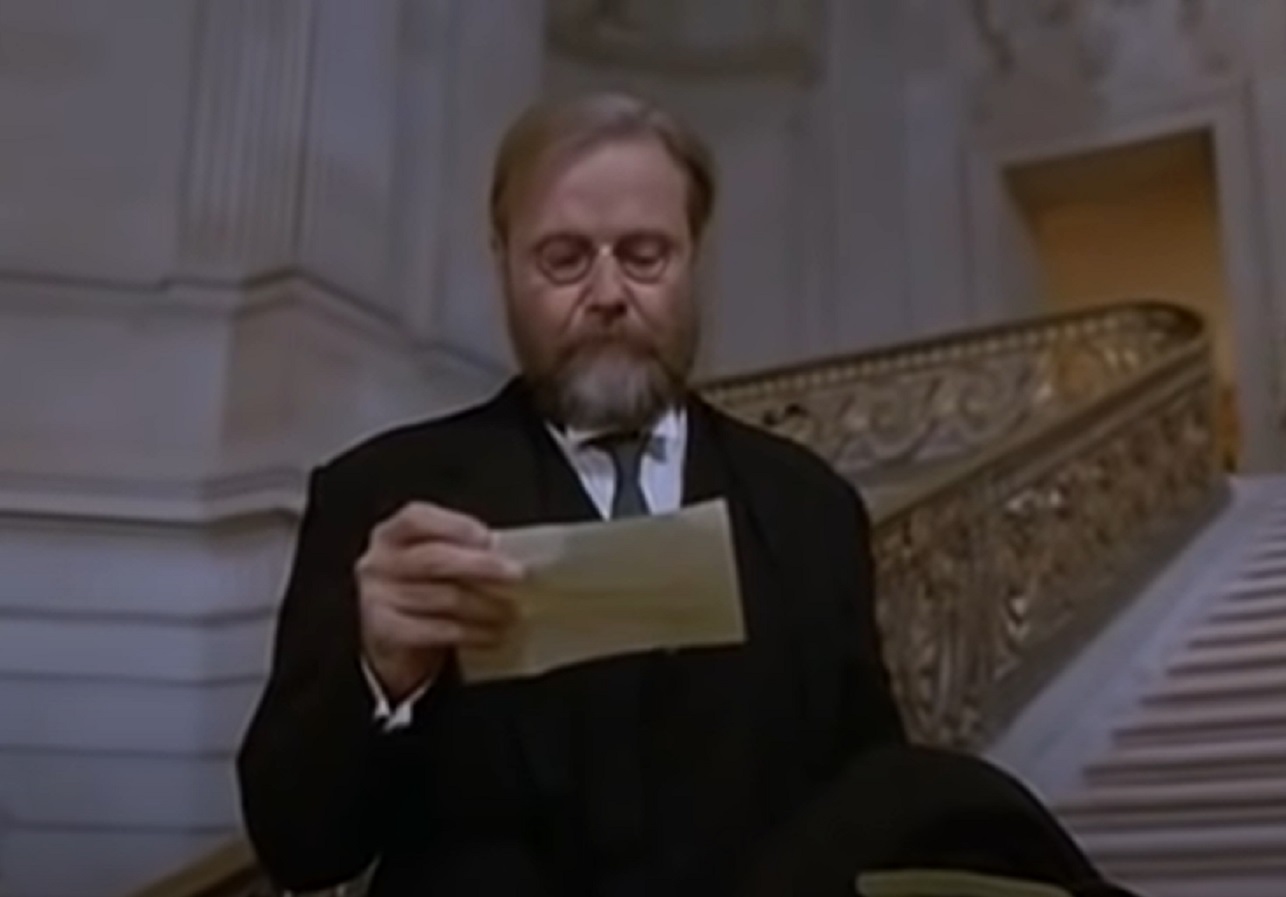

Alfred Kroeber, one of the main Berkeley anthropologists, was away from the state at the time of Ishi's passing. Yet even from all the way in New York, Kroeber sent mounds of telegrams trying to stop doctors from autopsying Ishi's body. Kroeber thought an autopsy was in violation of Yahi beliefs. It didn't work.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

The Autopsy

Whatever Ishi would have preferred when it came to an autopsy, we'll never know. But it was his old friend Saxton Pope, who was a stickler for hospital protocol, who performed the procedure despite Kroeber's objections.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

The Funeral

Even when they tried to do right by him, Ishi's colonizer friends didn't hit the mark. Although they preserved his brain, they had his body cremated—mistakenly thinking this was a Yahi practice.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Souvenirs Of His Life

The settlers also put a handful of items beside Ishi's body to be cremated: "one of his bows, five arrows, a basket of acorn meal, a boxfull of shell bead money, a purse full of tobacco, three rings, and some obsidian flakes."

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

His Resting Place

Ishi's associates then put his remains in Pueblo jar and interred him in Mount Olivet Cemetery near San Francisco.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

His Brain

Although Ishi's remains were cremated, there was still his preserved brain. Alfred Kroeber sent it to the Smithsonian Institution in 1917, where it stayed until 2000.

Renwick, James, Wikimedia Commons

Renwick, James, Wikimedia Commons

Back Home

Ishi's neurological remains were eventually recovered by the proper people. In accordance with the National Museum of the American Indian Act, in 2000 the Smithsonian repatriated what was left of Ishi, giving it to the descendants of the Redding Rancheria and Pit River tribes.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Another Homecoming

This process triggered an effort to return Ishi's cemetery remains as well. The tribal members who received these remains, however, wanted the utmost privacy. They kept the re-burial location a secret.

By then, researchers had made a shocking discovery.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Not The Last Of His Kind

While conducting the repatriation, Robert Fri, the director of the Museum of Natural History, announced that experts had traced Ishi's descendants to the Yana people of northern California (closely related to the Yahi). In other words, he still had descendants. There was more good news, too.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Life Finds A Way

Although still just a theory, some researchers believe that Ishi may not have been solely Yahi, but multi-ethnic. Steven Shackley, with the help of research by Jerald Johnson, believes that Ishi could have also been part Wintu, Maidu, or Nomlaki, which were all nearby tribes to the Yahi.

Michael Marmarou, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Michael Marmarou, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Complex History

If this theory is true, it indicates that the tribes may have intermarried under the external, colonial pressures they were facing. Traditionally, the Nomlaki and Wintu tribes were enemies of the Yahi, and would have competed for the same resources.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

Evidence Of Intermarriage

One of the biggest pieces of evidence for Ishi's multi-ethnicity is that he used what researchers called an "Ishi stick" to run long pressure flakes for his arrowheads. As this stick is a technique of the Nomlaki and Wintu tribes, Shackley thinks Ishi could have first learned it from a male relative who came from one of those tribes.

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

HBO,The Last of His Tribe (1992)

In Media

Many films and books have come out about Ishi since his passing. Perhaps the most famous was the biographical Ishi in Two Worlds by Alfred Kroeber's wife, writer and anthropologist Theodora Kroeber.