Once Mighty Now Dwindling

The Colorado River—once mighty, now dwindling. What drains this lifeline of the Southwest? The answer is a tangled web of missteps, miscalculations, and nature's fury. Let's swim through the story.

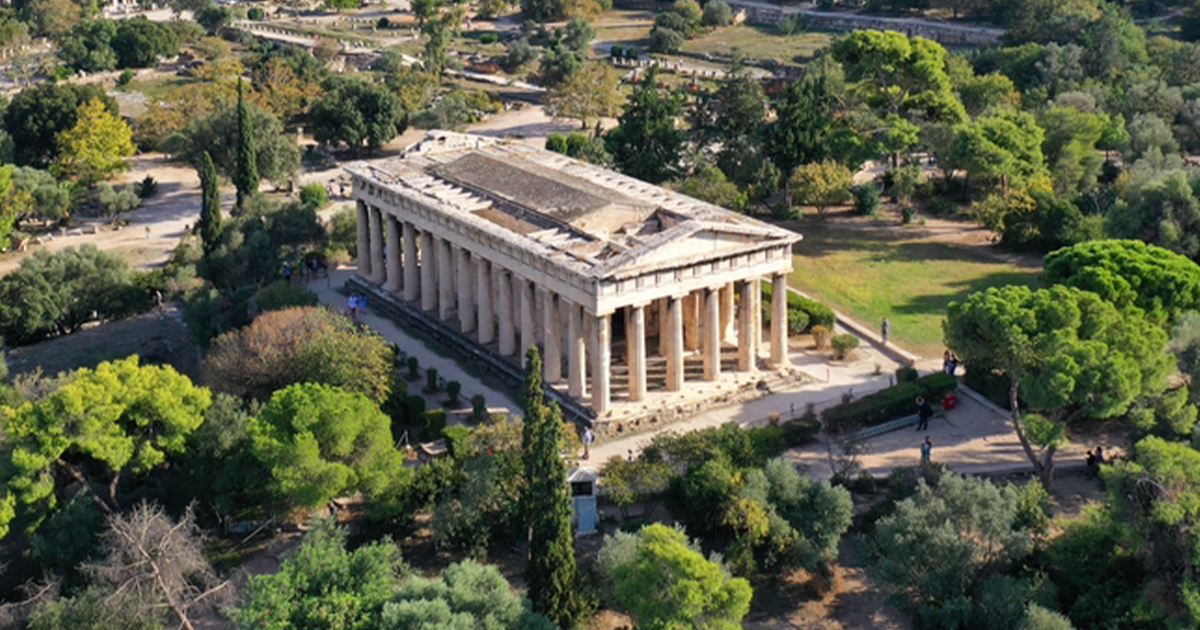

The River's Splendor

The Colorado River stretches 1,450 miles and traverses seven US and two Mexican states. It supplies water to over 40 million people who use it for survival. Its basin covers 246,000 square miles, making it a cornerstone of life in the region.

Adrille, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Adrille, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

What Feeds The River?

The Colorado River's main source is snowmelt from the Rocky Mountains, where seasonal snowpack acts as a natural reservoir, releasing water during spring and summer. Additionally, smaller tributaries like the Green River, Gunnison River, and San Juan River contribute significantly to its volume, ensuring a steady—though increasingly limited—supply.

Hogs555, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Hogs555, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

What The River Feeds

When you receive all, give some. Well, in this case, the Colorado River feeds some of the largest reservoirs in the United States. This includes Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Beyond these giants, the River supports numerous smaller lakes and waterways that sustain ecosystems, agriculture, and millions of people.

PRA, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

PRA, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

River Colorado's Amazing Journey

The beauty of the Colorado River? Its journey and here is a trickle: Upstream, in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, a small stream draining from the La Poudre Pass Lake at around 10,184 feet is where it all begins. The stream's name?

River Colorado's Amazing Journey

River Colorado's Amazing Journey

The Cache La Poudre River

This stream gracefully flows and joins the Colorado River. Along its banks, coniferous forests flourished, dominated by spruce, fir, and aspen groves. People also savored the beauty of the riparian vegetation, which included willows, grasses, and sedges.

Wusel007, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Wusel007, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

From La Poudre Pass To Grand Lake

Approximately 10 miles from the Pass, you enter Grand Lake, the largest natural lake in Colorado. Here, activities like hiking, fishing, and scenic drives rule the day. People can also camp along the lake's shores, savoring the mesmerizing sunrise and sunset of the panorama.

Muttnick, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Muttnick, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

From Grand Lake To Gore Canyon To Glenwood Springs

Twenty-five miles later, we got into the adrenaline-filled Gore Canyon, where whitewater rafting, kayaking, and camping were the activities of choice. From the Canyon, 50 miles away, Glenwood Springs graces the scenery. Want to indulge in some fishing or perhaps dip into hot springs? Glenwood Springs was the place.

Carol M. Highsmith, Wikimedia Commons

Carol M. Highsmith, Wikimedia Commons

From Glenwood Springs To Grand Junction To Moab To Hite Crossing

The journey through these four stops was equally exciting. So, after your hot springs dip, try a wine tasting at the vineyards in Grand Junction. Moab is home to Arches National Park, perhaps a safari. Hite Crossing presents you with another exploration through Canyonlands National Park.

Ken Lund from Reno, Nevada, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ken Lund from Reno, Nevada, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

From Hite Crossing To Lake Powell To Glen Canyon Dam To Lake Mead

The next stops are Hite Crossing, Lake Powell, Glen Canyon Dam, and Lake Meat. These collectively allowed river rafting, boating, fishing, and exploring the 11 parks along the way. After the Colorado River has graced all those locations and left so many memories on the way, it all ends at the…..

Lake Mead NRA Public Affairs, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Lake Mead NRA Public Affairs, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

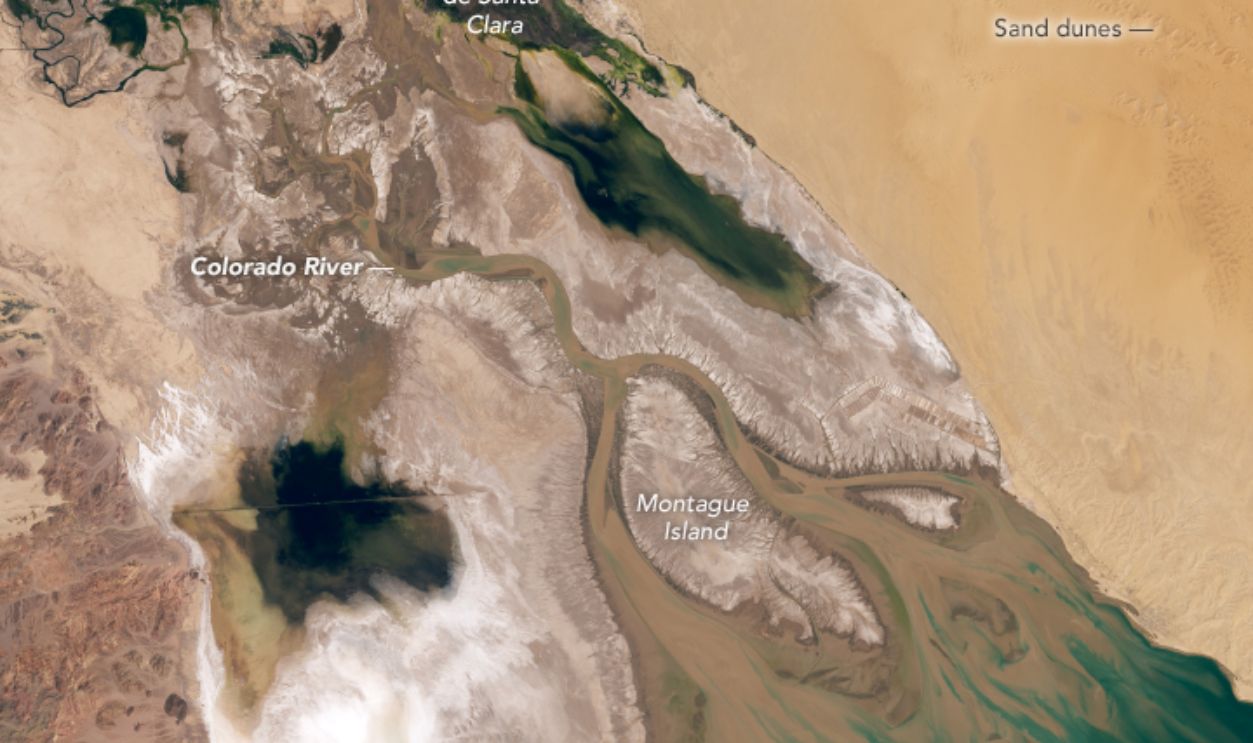

Final Destination, The Colorado River Delta

It will take you approximately 100 miles downstream from Lake Mead to the Delta. By now, the River has already slowed, meaning the activities are far more relaxed. We are talking about activities like bird watching, boating, and fishing. Next up is what man decided to include. But first….

Lauren Dauphin Wikimedia Commons

Lauren Dauphin Wikimedia Commons

Honorable Mentions

If we speak of the Colorado River without mentioning its glorious features like the Grand Canyon and the Horseshoe Bend, we've missed the mark. But it's not the only one because you'll also find more canyons (Marble, Antelope, Glen, Cataract, Black, and Westwaters) and narrows like The Narrows.

Charles Wang, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Wang, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Constants Along The Way

Along its banks, you can find vegetation rich in cottonwood trees, willows, and the invasive tamarisk. Bighorn sheep, beavers, Mohave rattlesnakes, mule deers, and a couple of bird species like herons, egrets, and ducks call these banks home.

Lake Mead NRA Public Affairs, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Lake Mead NRA Public Affairs, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Man-Made Features Along The Colorado River

Until here, it's been green, fresh, and flowy. However, as with most things, the results can sometimes be a downtrend when humans interfere. Unfortunately, this was the case with the Colorado River. The two main constructions were the Hoover Dam and the Glen Canyon.

APK, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

APK, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Food For Energy

These reservoirs provide water storage, hydroelectric power, and recreational opportunities. Firstly, on the energy front, the power plants are the Hoover Dam and Glen Canyon Dam. These have historically produced significant amounts of electricity.

Adbar, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Adbar, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Power At Its Peak

At their peak, these plants made a splash, generating over 4,000 megawatts annually and providing power to millions of homes across the Southwest US. For your information, the Southwest includes Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah.

High Contrast, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

High Contrast, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

But Water Is A Limited Resource

Just like any other resource on the planet, urban and rural planners have to set the right numbers so that the resource lives to feed people for generations. Well, here is where all the problems started rolling in. The planners got it wrong right from the start.

mark byzewski, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

mark byzewski, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

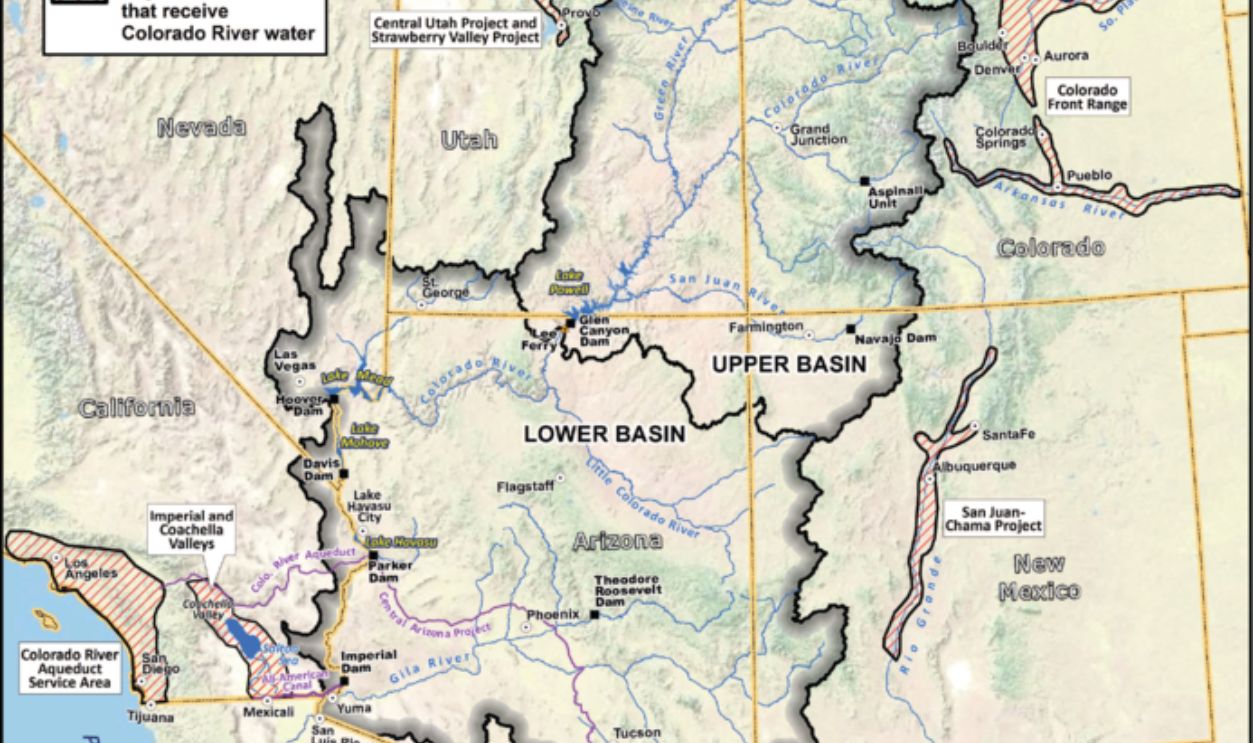

Divided Into Half

When 1922 came, six states signed the Colorado River Impact. This impact divided the River's flow into two parts: the upper basin and the lower basin. The upper basin covered parts of Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Wyoming, and a small portion of Arizona.

MostlyDeserts, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

MostlyDeserts, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Lower Basin

This lower basin covered Arizona, California, Nevada, and parts of New Mexico and Utah. Both basins were allocated 7.5 million acres per foot. The engineers estimated this to be half of the River's yearly flow. Was it correct? Of course not.

Grand Canyon National Park, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Grand Canyon National Park, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Overestimated From The Start

The 1922 Colorado River Compact was built on flawed data from an unusually wet period. This led to an unsustainable water distribution among the seven states that rely on the River. Early estimates assumed 20 million acre-feet of annual flow, but reality often hovers around 12.5 million acre-feet.

US Bureau of Reclamation, Wikimedia Commons

US Bureau of Reclamation, Wikimedia Commons

A Thirst Unquenchable

The mouths the water fed were also rising. In fact, in the mid-20th century, post-war booms and expanding cities like Las Vegas and Phoenix placed enormous demands on the River. Agriculture—especially thirsty crops like alfalfa—further strained the resource.

Rennett Stowe from USA, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Rennett Stowe from USA, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

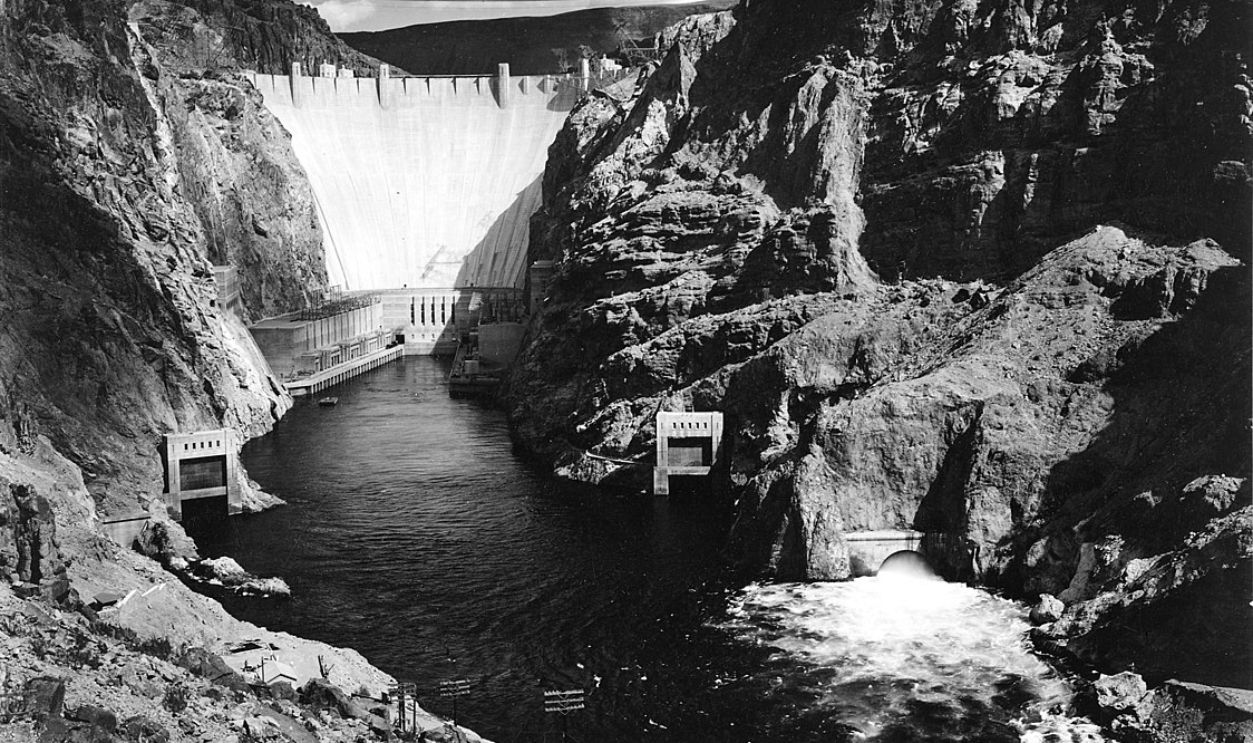

Engineering Marvels Turned Environmental Disasters

As the population grew, the Hoover and Glen Canyon Dams were built. The Hoover stands between Nevada and Arizona, and it was constructed between 1931 and 1936 by the US Bureau of Reclamation with the help of several contractors.

Ansel Adams, Wikimedia Commons

Ansel Adams, Wikimedia Commons

Reasons For Hoover Dam

The primary reasons for building the Hoover Dam were to provide flood control, water storage, hydroelectric power, and irrigation for the arid regions of the Southwest. The dam created Lake Mead, one of the largest artificial lakes in the world. Mead supplies water to millions in Nevada, Arizona, and California.

Mariordo (Mario Roberto Durán Ortiz), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mariordo (Mario Roberto Durán Ortiz), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Magnificent Glen Canyon

The Glen Canyon took up about 169.6 miles, and you'll find this splendor of human ingenuity in Utah. A small portion of it dubs its feet into Northern Arizona. It begins at the confluence of the Colorado River and the Dirty Devil River and ends near Lee's Ferry.

NPS Photo/Gary Ladd, Wikimedia Commons

NPS Photo/Gary Ladd, Wikimedia Commons

Glen Canyon Created Lake Powell

The construction of Glen Canyon Dam in 1963 created Lake Powell, another significant reservoir that provides water storage, hydroelectric power, and flood control for the arid southwestern US. However, like its predecessor, the dam has also had significant environmental impacts.

PRA, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

PRA, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Issues Ensued

When you transform a river into a reservoir, you first disrupt its natural flow. While the positives were to provide hydroelectric power and water storage, they devastated downstream ecosystems and sapped all its vitality. Additional issues were blocking sediment flow and altering the natural ecosystem, especially agriculture.

Stacey Smith, Wikimedia Commons

Stacey Smith, Wikimedia Commons

Agriculture Became A Double-Edged Sword

Another plus that turned into a negative is that Colorado irrigated 5.5 million acres of farmland, 80% of which was for agriculture. The salt on the injury was that the crops were exported—almonds and lettuce. This left less for domestic needs. Let's call it water exportation in another form.

Scott Bauer, USDA ARS, Wikimedia Commons

Scott Bauer, USDA ARS, Wikimedia Commons

From The Frying Pot Into The Fire, Literally

As things were changing downstream, upstream was also seeing a rise in temperature and prolonged drought, which further hammered the River's flow. Snowpack—essential for spring melt—has dwindled by 20% since the 1980s, further limiting water supply downstream.

Lake Mead's Decline

Lake Mead, the River's largest reservoir, now operates under a Tier 1 shortage. Water levels dropped to reach the drought trigger elevation level of 1,075 feet in late 2010. This prompted reduced allocations for states like Arizona and Nevada. Lake Powell had a similar fate.

Lake Powell's Water Level

Due to two dry spells between 2000 and 2004, Lake Powell saw a decline in its water levels to a third of its full capacity. This was the lowest it had ever been since 1969. In 2014, the Bureau of Reclamation cut its release by 10%. The water levels dropped lower.

Scotwriter21, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Scotwriter21, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

All This Because States Couldn't Agree

You see, if nothing was to be done, cuts and all, the fate of the Colorado River hung in the balance. The lower basin states could not come to an agreement, so the Bureau of Reclamation took the legal route: reducing the releases from both dams in 2023.

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

Why?

If the cuts didn't happen, then no more power from Glen Canyon Dam. Arizona and California went on a head-to-head contest to negotiate the cuts. Spoiler alert! It was at the expense of each other. Arizona to cut Carlifionia's allocations. California to cut allocations to Arizona.

Grand Canyon NPS, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Grand Canyon NPS, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Federal Government Had To

The Federal government had to step in and cut the allocations equally between California, Arizona, and Nevada in April 2023. Since then, they have also been working to recycle the River's water, boost efficiency, and reduce water usage by giving grants.

Charles O'Rear, Wikimedia Commons

Charles O'Rear, Wikimedia Commons

Mexico's Drying Delta

Today, there's barely a trickle when the Colorado River reaches Mexico. The once-lush delta is now arid, starving ecosystems and communities reliant on its flow. The biggest losers are the wildlife: Jaguars and vaquita porpoises, which roam freely in the jungle here and have no home.

A pulse of water revives the dry Colorado River Delta by Los Angeles Times

A pulse of water revives the dry Colorado River Delta by Los Angeles Times

The Lush Green Turned Brown

The spectacular green vista is now a dried locale. Of the 49 native fish species, 42 are endemic; if they go extinct, they go forever. Today "where now there is only powder-dry desert, the grass once reached as high as the head of a man on horseback".

A pulse of water revives the dry Colorado River Delta by Los Angeles Times

A pulse of water revives the dry Colorado River Delta by Los Angeles Times

Water Sports But For Ownership

It's not the water sports you were waiting for, right? Well, there have been plenty of litigation battles among states, tribes, and municipalities that have further stalled efforts to create sustainable solutions. And boy, are there plenty. First, Arizona vs. California (1963); Cali won 4.4 million acre-feet of water annually.

Larry D. Moore, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Larry D. Moore, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Urban Vs. Rural

The next battle was the Colorado River Indian Tribes vs. the United States (2004). Here, the Tribes won by getting more water allocations. Then, in 2007, Nevada went against the United States, winning more water from Lake Mead. In 2010, the Hualapai Tribe won against the government and got more water allocated.

Chris English, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Chris English, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Failed Conservation Efforts

This back-and-forth over the years has stifled all programs aimed at reducing water consumption. Despite efforts to curb usage, the River's decline continues unabated, which has revealed the difficulty of enacting effective change.

J Brew from near Seattle, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

J Brew from near Seattle, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Industry's Footprint

Did we mention that gold and silver were mined along the River? Yes, there was, and that also caused some issues. The runoff from these sites polluted the water and wiped off more native flora and fauna.

Riverhugger, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Riverhugger, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Environmental Fallout

From energy production to mining, industries in the Colorado River Basin consume vast amounts of water. Many operations fail to prioritize conservation, adding to the River's woes. As water levels drop, habitats dwindle. Endangered species like the razorback sucker and humpback chub face heightened threats.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters, Wikimedia Commons

What Happens If It All Dries Up?

Firstly, all the 40 million mouths this River feeds have to seek alternatives. Secondly, no more hydroelectric power, meaning power rationing and shortages in the region. Next, all the agriculture, tourism, and recreation practices go—no water, no jobs, and no fun.

National Park Service, Michael Quinn, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

National Park Service, Michael Quinn, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Extinctions And Shortages Left, Right, And Center

As things are right now, they will get worse. There will be no more birds to watch, trees to house them, and animals to roam, not to mention the disarray due to water shortages. The litigations and public outcry against the government will only worsen if nothing changes.

Ej Lowell, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ej Lowell, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Global Lessons

The Colorado River's decline offers a cautionary tale for other major rivers worldwide. Overuse, climate change, and poor planning can devastate even the mightiest waterways. If nothing changes soon, the 250,000+ people working on jobs linked to the River will lose everything.

Ken Lund from Reno, Nevada, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ken Lund from Reno, Nevada, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Is There Hope?

Of course, there is hope, but it will take everyone's effort. Restoring the Colorado River requires bold actions—rethinking water allocations, investing in sustainable agriculture, and addressing climate change head-on. Collaboration is key to reversing its decline. A better and far-fetched option?

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), Wikimedia Commons

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), Wikimedia Commons

Hypothetically, Cut All Water Usage

That would be to just cut all usage for a few years. But as we know, that is almost impossible. So, small changes would suffice: conserve water at home, support policies addressing climate change, and advocate for sustainable practices. Every drop saved helps preserve this vital resource.

Nadiatalent, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Nadiatalent, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons