Lost In The Arctic

Led by John Franklin, this was a British Arctic adventure that didn't go exactly as planned. What began in 1845 as an ambitious push to discovery ended up becoming a questionable, haunting mystery.

The Initial Setup

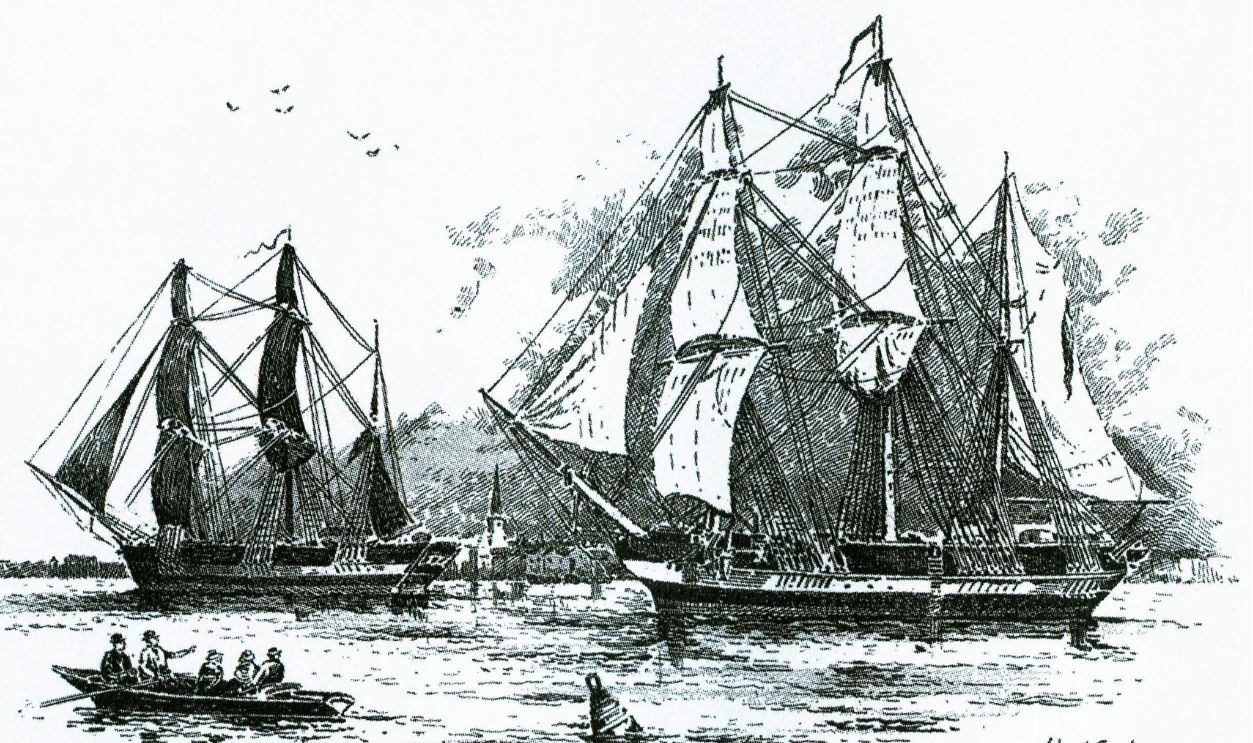

In 1845, the British Admiralty launched its biggest expedition to the Arctic ever. Two ships named HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, set sail with Sir John Franklin and a crew of 129 others. They had one serious goal in mind: Find the Northwest Passage.

The Illustrated London News, ILN staff Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Illustrated London News, ILN staff Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Side Quests

Along with that, the goal was to gather magnetic data to help with navigation. They were loaded up with three years' worth of supplies, including canned food from a man named Stephen Goldner. This was literally Britain's best shot at cracking a mystery.

Stephen Pearce, Wikimedia Commons

Stephen Pearce, Wikimedia Commons

The Ships' Technology

HMS Erebus and HMS Terror were great examples of Victorian engineering. Mainly because these ships had railway engines that were adapted to power screw propellers, which in turn allowed them to reach speeds of 7.4 kilometers per hour with the use of steam.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Smart Heating Systems

Their bows were reinforced with layers of wood and iron for extra protection against ice. They even had smart steam heating systems to keep the crew warm and special wells that let the propellers and rudders retract into the hull. This shielded them from ice damage.

François Musin, Wikimedia Commons

François Musin, Wikimedia Commons

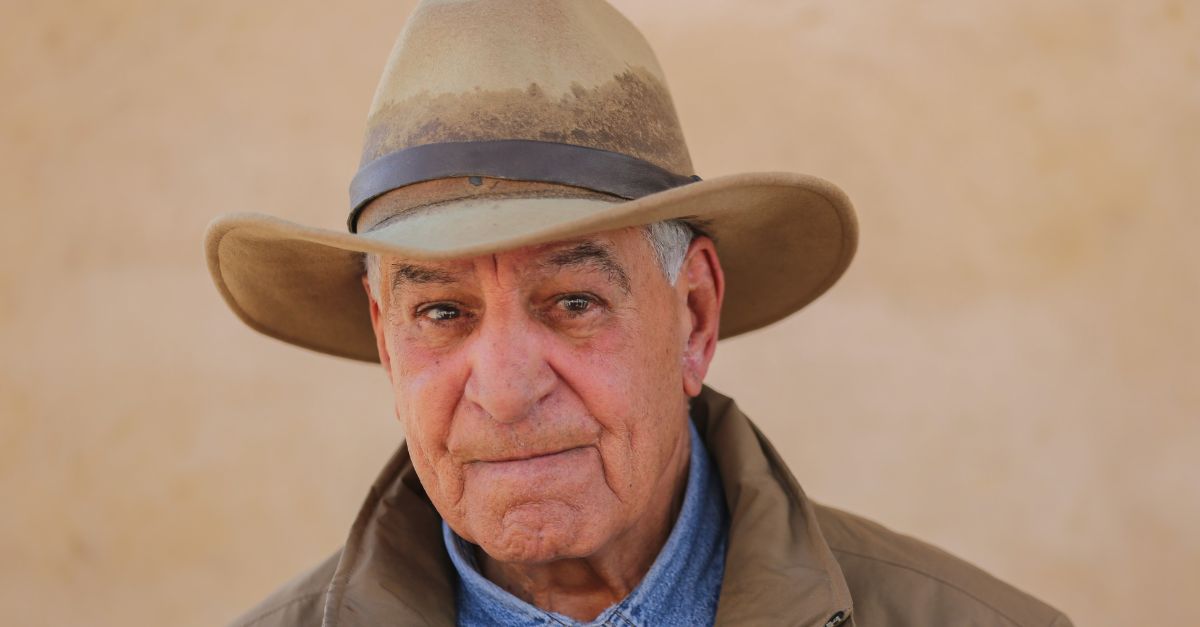

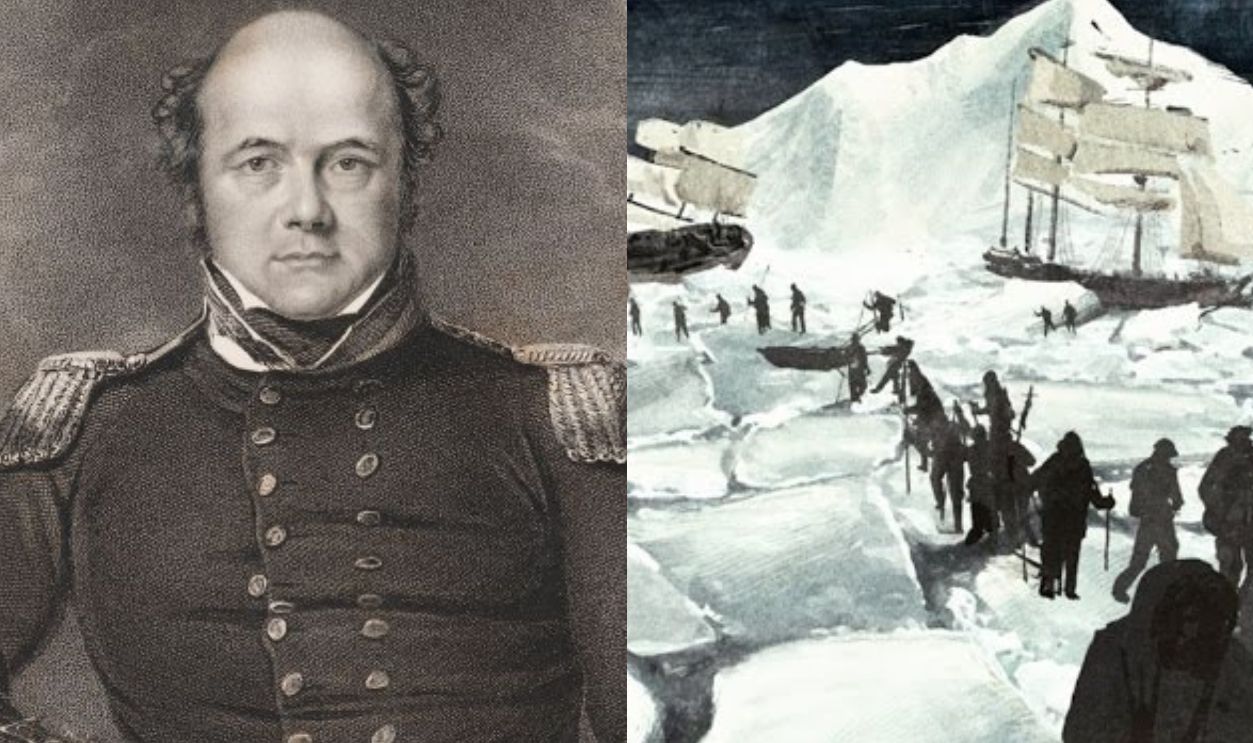

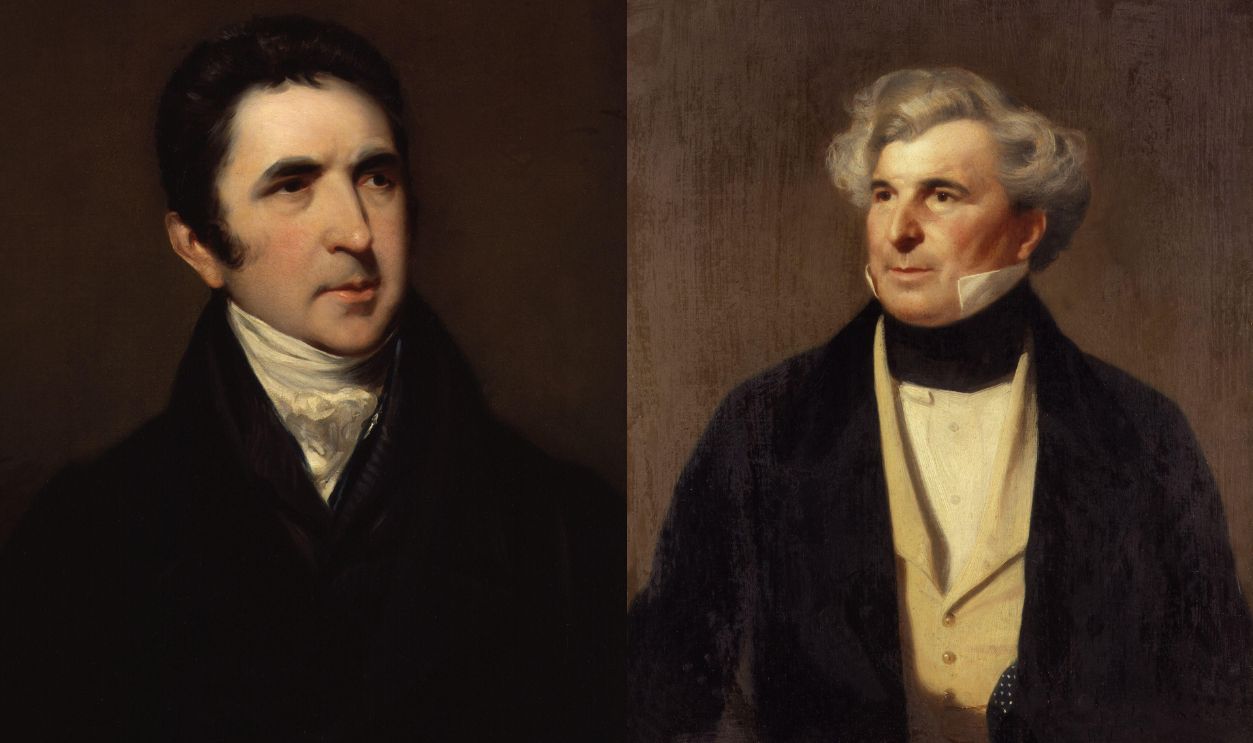

Leadership Selection

Sir John Barrow, the Second Secretary of the Admiralty, had to pick the leaders for the expedition carefully. His first two choices had turned him down. Basically, James Clark Ross didn't want to do any more polar exploration because he made a promise to his wife.

National Portrait Gallery and Stephen Pearce, Wikimedia Commons

National Portrait Gallery and Stephen Pearce, Wikimedia Commons

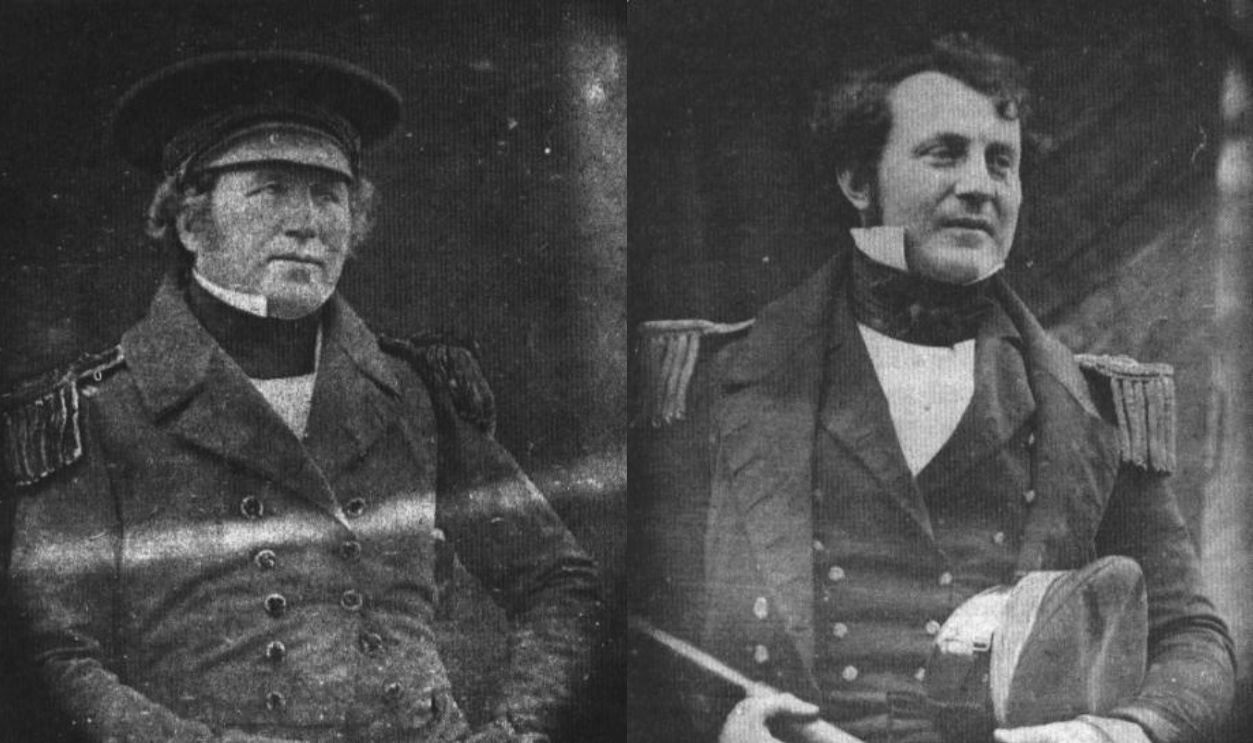

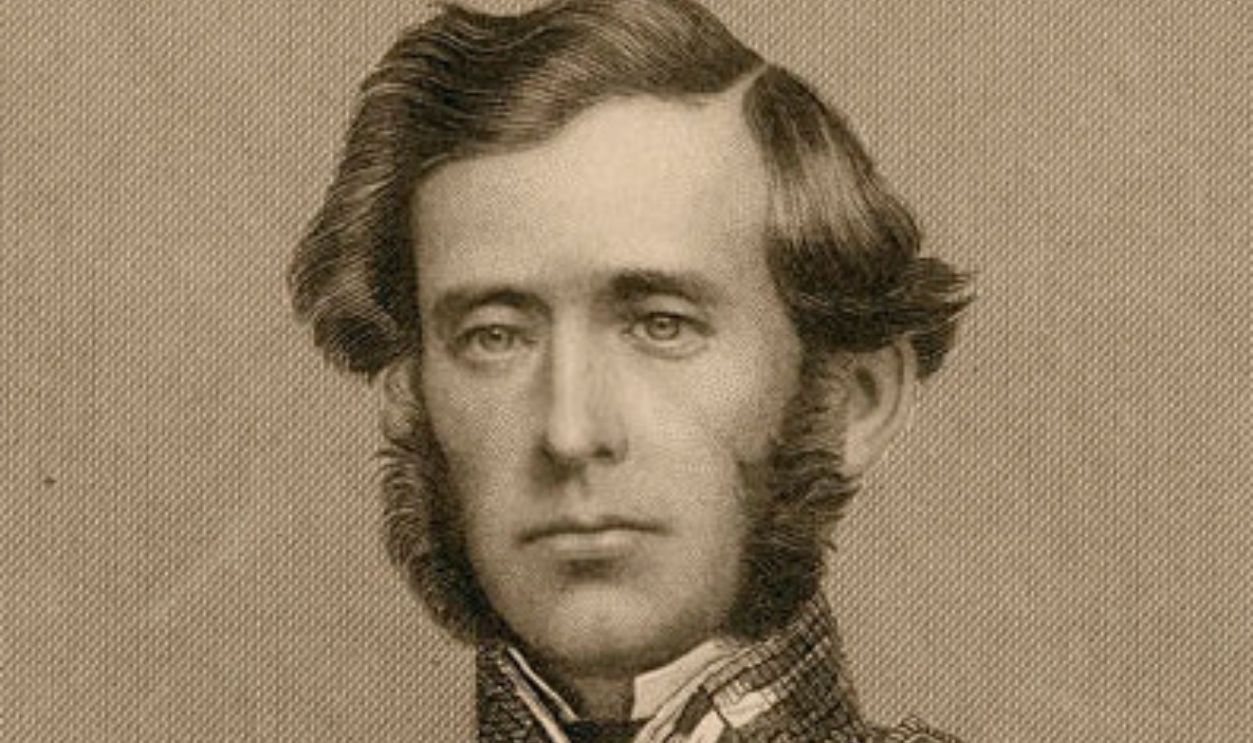

The Men At The Helm

And William Parry just claimed to be tired of Arctic ventures. So, Barrow ended up choosing the 59-year-old Franklin. The modest Francis Crozier ultimately became the captain of the Terror, while James Fitzjames took on the role of Franklin's second-in-command on the Erebus.

Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier and Richard Beard, Wikimedia Commons

Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier and Richard Beard, Wikimedia Commons

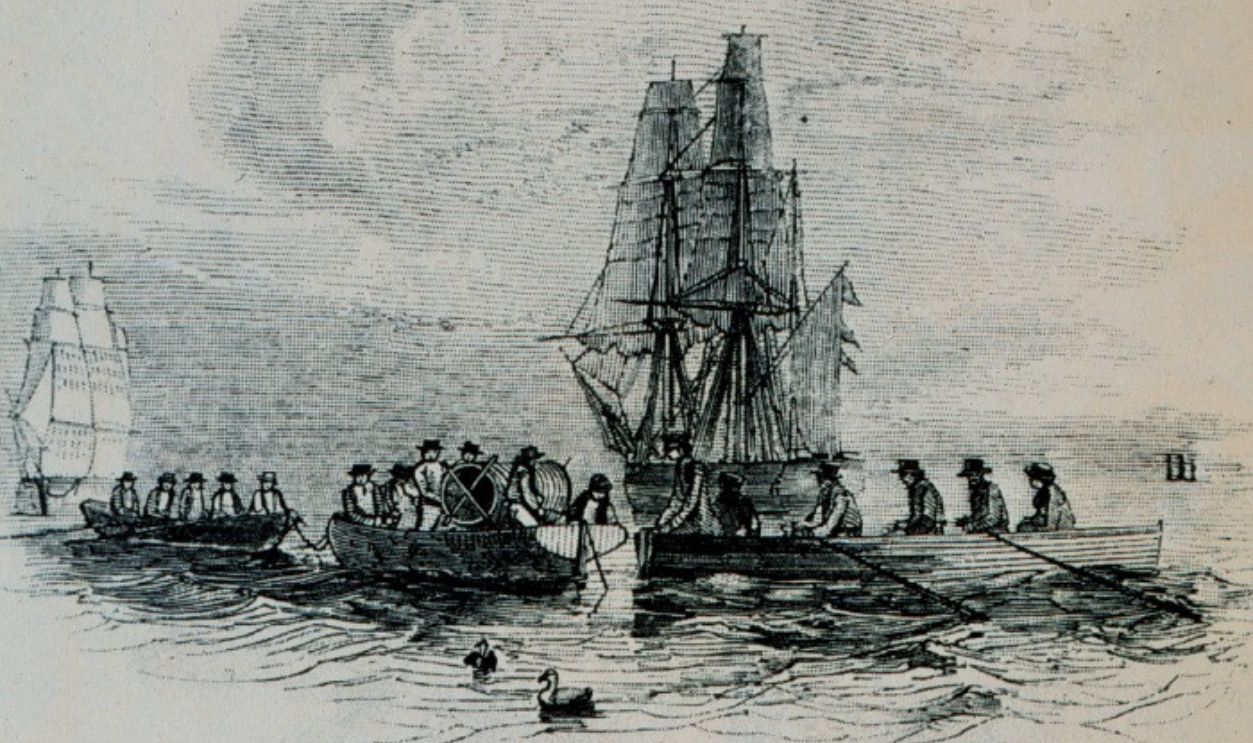

The Departure Begins

On May 19, 1845, the expedition began from Greenhithe, and guess what? They had some unexpected companions. One was a monkey named Jacko, a Newfoundland dog named Neptune, and a cat. Their first pit stop was Stromness, Scotland, where they needed fresh livestock.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)/Wikimedia Commons

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)/Wikimedia Commons

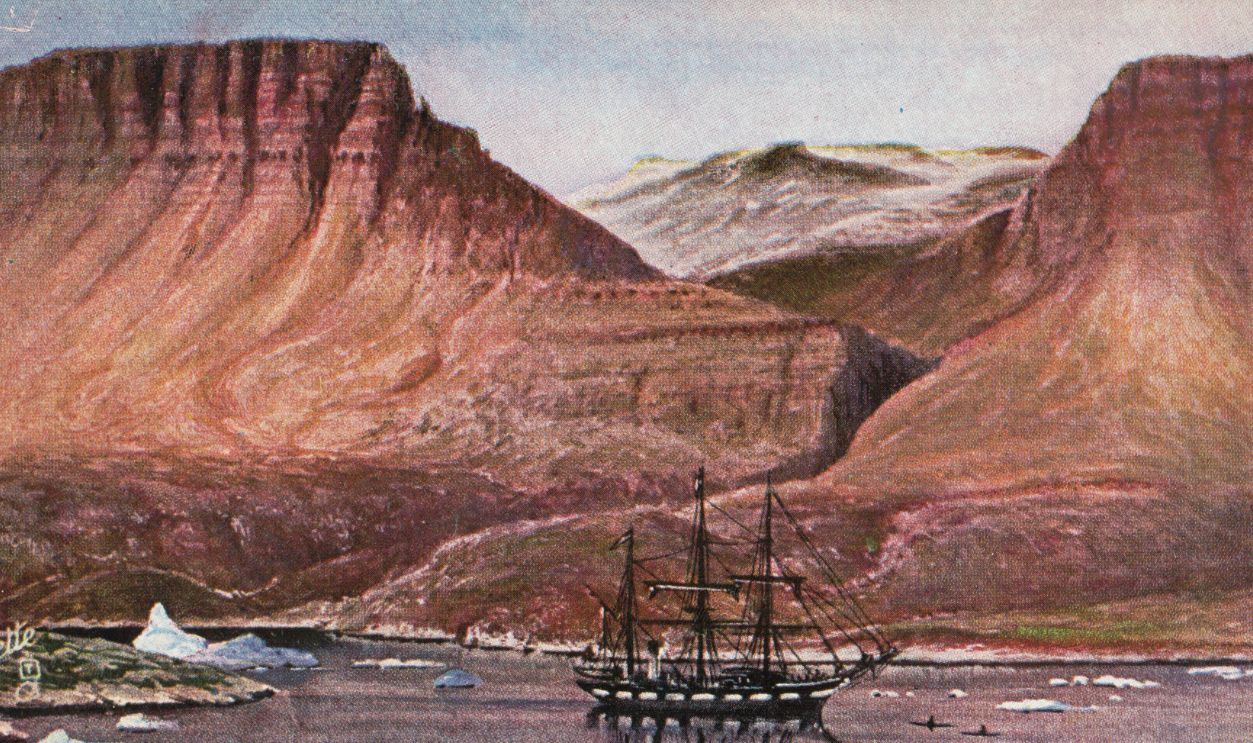

Hiccups Along The Way

By early July, they made it to Disko Island in Greenland, where five crew members who caught tuberculosis had to head back home. The last time they connected with Europe was on July 26, 1845, when they encountered some whaling ships in Baffin Bay.

Unknown Author/Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author/Wikimedia Commons

First Signs Of Trouble

Apparently, the first winter of the expedition in 1845–46 was tough at Beechey Island. And unfortunately, three crew members lost their lives. These were John Torrington, who died on January 1, followed by John Hartnell on January 4, and William Braine, who passed in April.

Gordon Leggett, Wikimedia Commons

Gordon Leggett, Wikimedia Commons

Stuck In Ice

What's terrible is that some ship rats even got to William Braine's body before they could bury him. After leaving Beechey Island, the ships made their way down Peel Sound toward King William Island, but they got stuck in the ice for good on September 12, 1846.

After George Back, Wikimedia Commons

After George Back, Wikimedia Commons

The Fatal Turn

The ships reportedly got stuck in the ice of the Victoria Strait near King William Island. On June 11, 1847, Franklin sadly passed away, the cause for which remains uncertain. After that, Francis Crozier took over as the captain, and he had Fitzjames as his right-hand man.

Things Only Got Worse

The crew seemed to face two brutal winters from 1846 to 1848, stuck in the same spot. Their supplies ran low, and things just kept getting worse. Finally, on April 22, 1848, the rest decided to leave both ships behind and started a trek south towards the Canadian mainland.

The Disturbing Disappearance of the Franklin Expedition by Scary Interesting

The Disturbing Disappearance of the Franklin Expedition by Scary Interesting

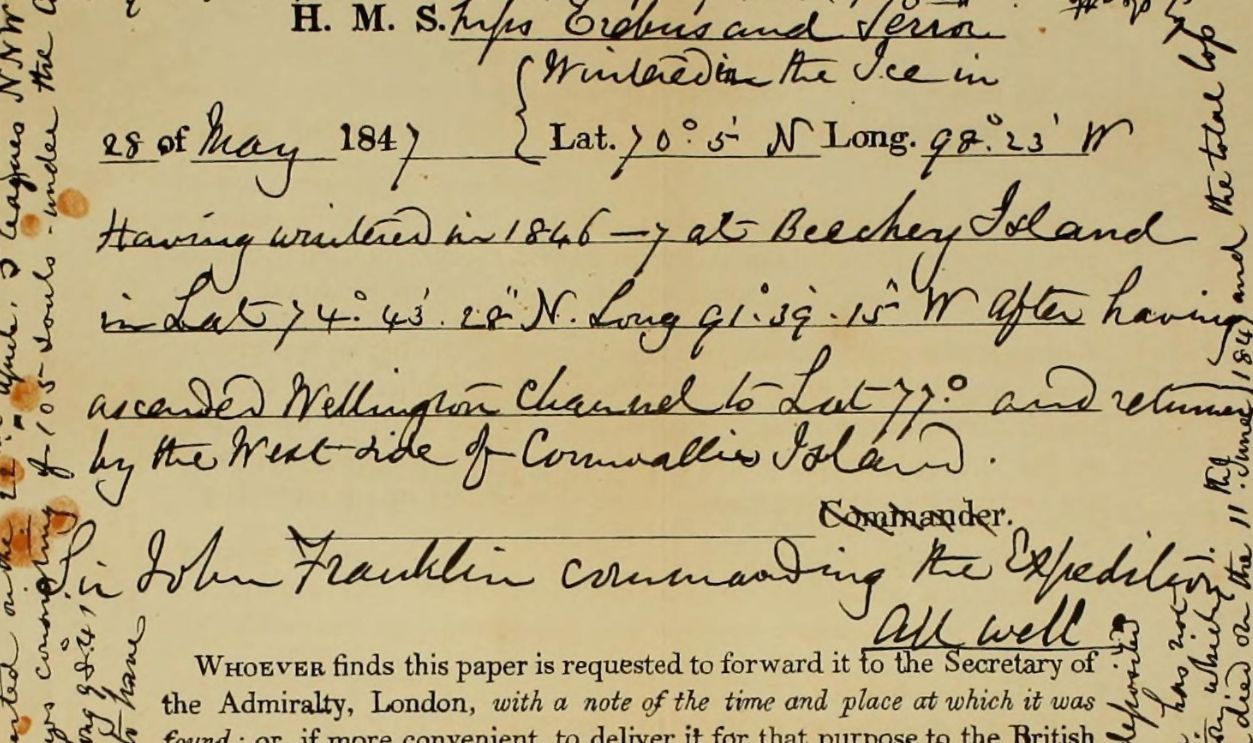

The Victory Point Note

It is said that in May 1859, searchers stumbled upon a message in a pile of stones at Victory Point that shed some light on what happened during the expedition. The note was in two parts: the first from May 1847 and the other, April 1848.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Difference A Year Can Make

The first part said everything was "all well". But the second part, dated April 25, 1848, told a much darker story. It said that Franklin was dead, and 24 others had died, too. The 105 survivors were planning to head towards Back River. This is the only direct written record available.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Lady Franklin's Campaign

But Jane Franklin wasn't about to sit back quietly after her husband disappeared. By 1848, she had managed to convince the Admiralty to start search operations, which initiated a three-pronged search strategy. This turned into the biggest rescue mission in British naval history.

Australian Government - Department of the Environment and Water Resources, Wikimedia Commons

Australian Government - Department of the Environment and Water Resources, Wikimedia Commons

The Dedication

She even dipped into her own bank account to fund more searches and kept the public interested through media campaigns. Her relentless effort led to many expeditions that, even though they didn't bring the crew back, mapped out thousands of miles of Arctic coastline.

Thomas Bock, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Bock, Wikimedia Commons

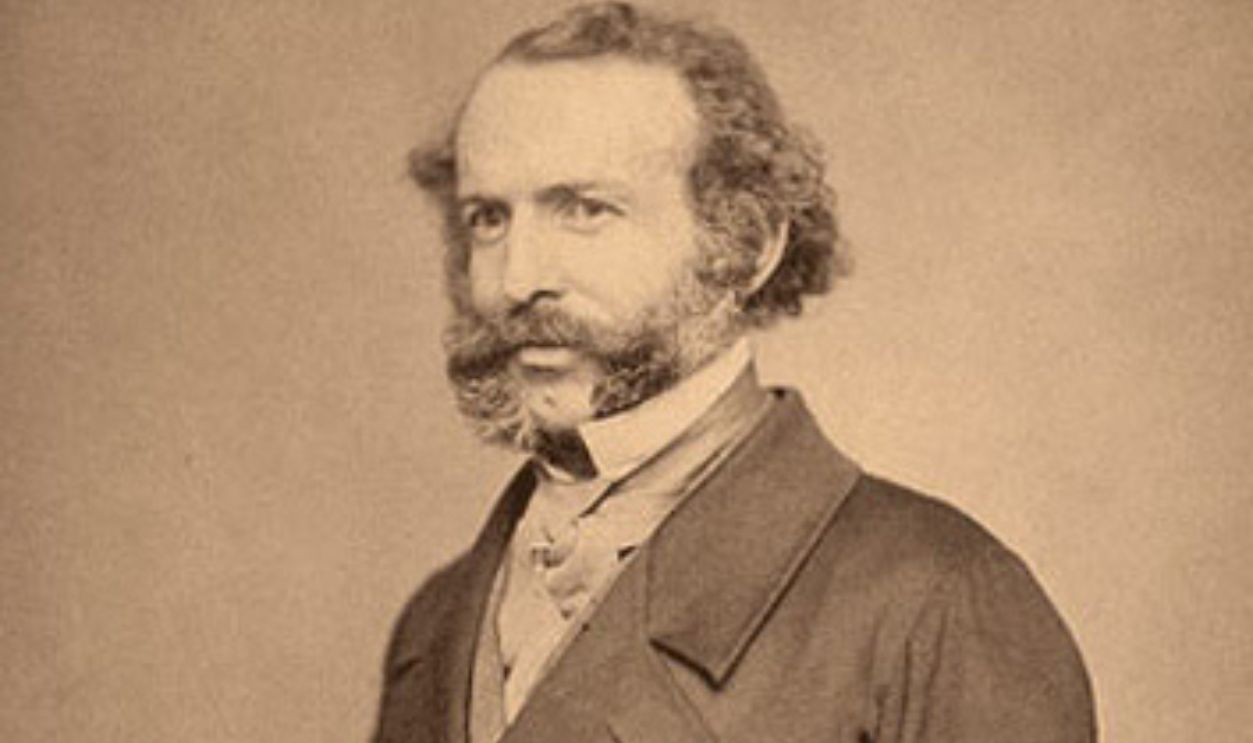

The Grim Discoveries

In 1854, Dr. John Rae, an Arctic explorer, talked to the Inuit (indigenous folks living in the Arctic), who shared some shocking information. They told him that around 35 to 40 guys were found dead near Back River. In addition to this, there were signs of cannibalism among the crew.

Henry Maull, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Maull, Wikimedia Commons

The Stories Were Confirmed

Obviously, this news freaked out Victorian society, causing literary elites like Charles Dickens to strongly deny it. However, later on, certain archaeological discoveries that included cut marks on bones found at different sites ended up confirming these unsettling stories.

Jeremiah Gurney, Wikimedia Commons

Jeremiah Gurney, Wikimedia Commons

Scientific Findings

Recent studies of the crew's remains reveal that they could have succumbed to various health issues. Some were detected with scurvy, pneumonia, and TB. It's also possible that poorly sealed food cans poisoned them with lead, which might have contributed to their deaths.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Perished In The Cold

Apart from this, some more research from 2016 found that not getting enough zinc for the body could have entirely messed with the crew members immune system. Even the one who managed to survive the toughest times eventually succumbed to cold and starvation.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

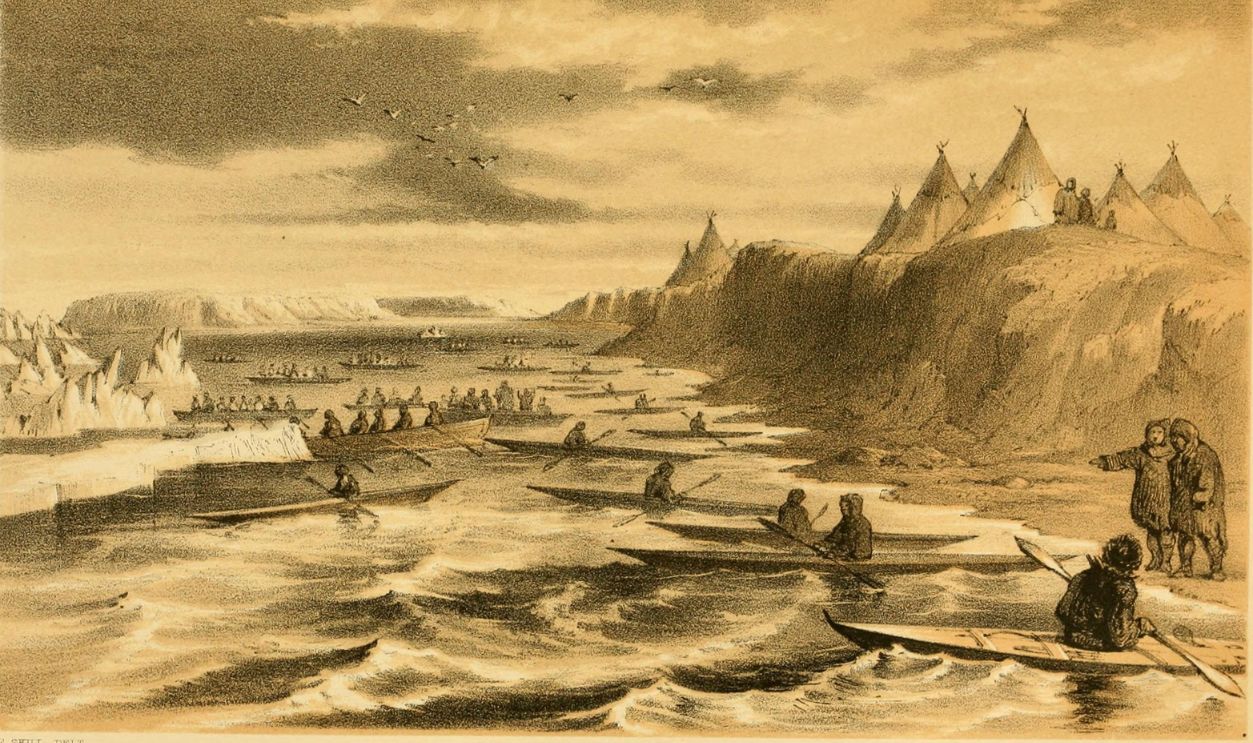

The Inuit Connection

Local indigenous people had provided some really valuable info about what happened to the expedition, but at first, no one in the then-Victorian society took them seriously. They even talked about seeing crew members in bad shape and evidently finding lifeless bodies.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

They Were Right All Along

Their stories included a ship that washed up on shore and got salvaged and another one that sank with people still on it. For over a hundred years, no one listened to these accounts, but when the ships were finally found, the Inuit's tales turned out to be spot on.

James Wilson Carmichael, Wikimedia Commons

James Wilson Carmichael, Wikimedia Commons

Discovery Of Erebus

After about 169 whole years of thorough searching, Parks Canada finally found the ship HMS Erebus on September 7, 2014. It was spotted in Wilmot and Crampton Bay, just 80 km south of King William Island. The ship was sitting in just 11 meters of water and was pretty well preserved.

Unearthing the Erebus by Canada's History

Unearthing the Erebus by Canada's History

Sonar Tech

The discovery was made possible through a combination of modern technology and insights from Inuit oral traditions. They used side-scan sonar and found intact deck planking, and later dives recovered a bunch of artifacts. The sonar revealed a promising target that appeared distinctly on the screen.

Unearthing the Erebus by Canada's History

Unearthing the Erebus by Canada's History

Initial Findings

So, the day before they made the big discovery, archaeologists came across some artifacts on a nearby island that matched parts of HMS Erebus, like a davit pintle that's used for raising small boats. This really boosted their confidence that they were getting close to finding the ship.

Unearthing the Erebus by Canada's History

Unearthing the Erebus by Canada's History

Finding Terror

Finally, the Arctic Research Foundation found HMS Terror on September 3, 2016, in a spot called Terror Bay, which is south of King William Island. The ship was found to be sitting 24 meters (79 feet) underwater and was also surprisingly in great shape.

Parks Canada Guided Tour Inside HMS Terror by Parks Canada

Parks Canada Guided Tour Inside HMS Terror by Parks Canada

Special Marking

Remote underwater vehicles showed that Terror wasn't abandoned at anchor, as its anchor cables remained secured along the bulwarks. A distinct exhaust pipe rising from the deck helped confirm the ship's identity, matching the location where the smokestack for Terror's locomotive engine had been installed.

Parks Canada Guided Tour Inside HMS Terror by Parks Canada

Parks Canada Guided Tour Inside HMS Terror by Parks Canada

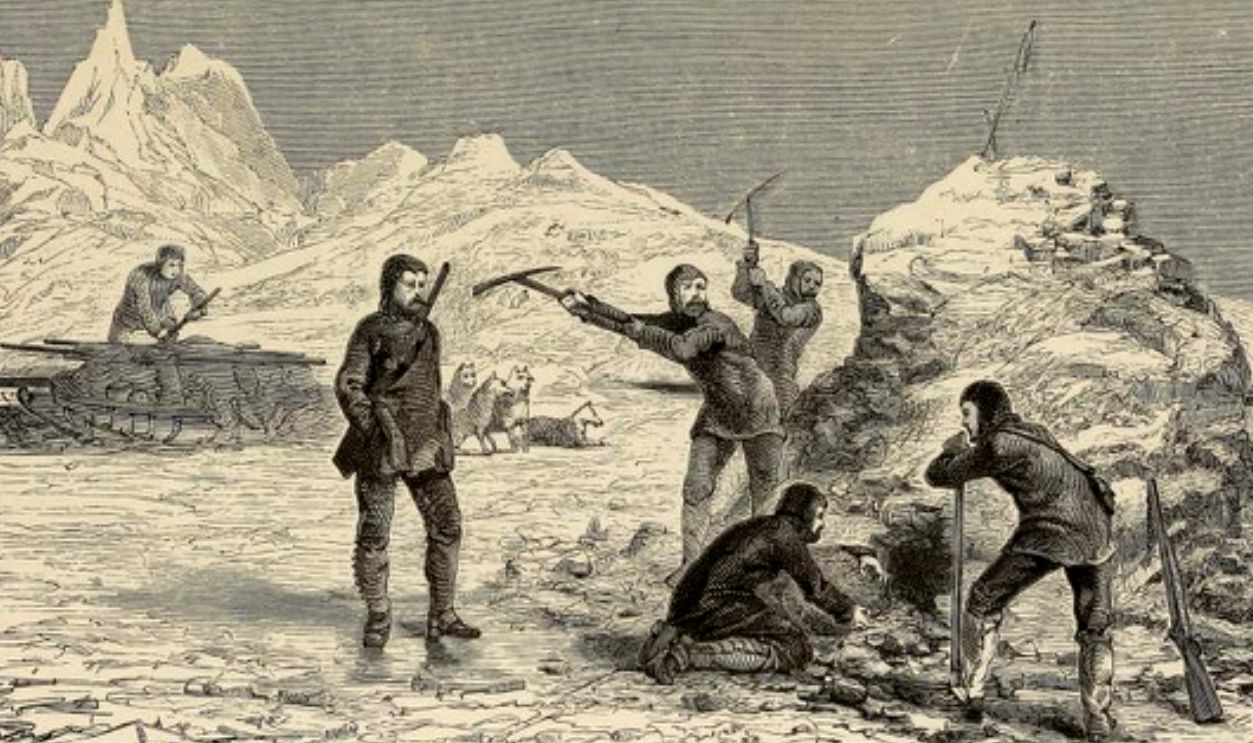

The Death March

After abandoning their ships in April 1848, 105 survivors set sail on a tough journey towards the south. They dragged boats, heavy gear, and supplies across King William Island in order to reach Back River. McClintock eventually found one of the boats with two skeletons inside.

Walter W. May, Wikimedia Commons

Walter W. May, Wikimedia Commons

Who Lives, Who Dies

Along with this, a bunch of personal stuff like books, boots, silk handkerchiefs, and toiletries were also found. All that extra cargo probably slowed them down a lot. Most of the crew members didn't make it to the island, but around 40 did make it to the mainland before they expired.

Walter W. May, Wikimedia Commons

Walter W. May, Wikimedia Commons

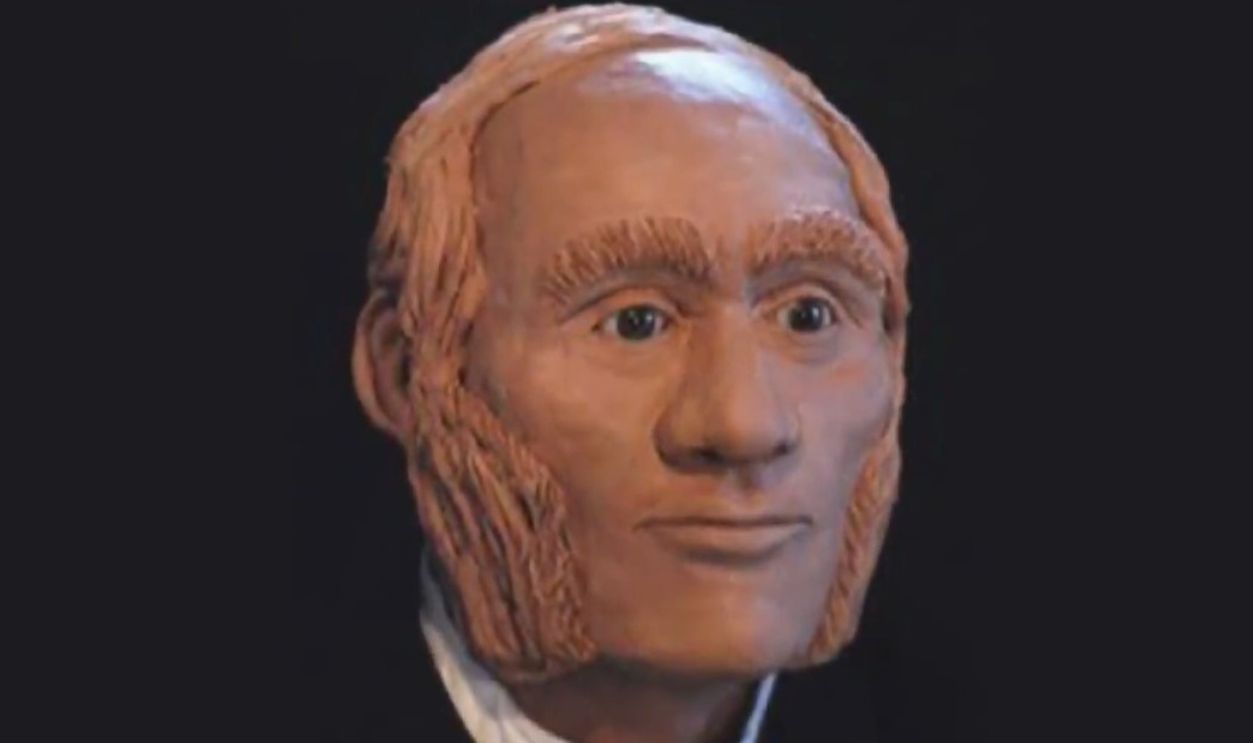

Modern Identifications

Recent DNA testing has helped identify some remains that were found earlier. Reportedly, in 2021, researchers managed to match the DNA of Warrant Officer John Gregory from HMS Erebus with that of his great-great-great-grandson, who lives in South Africa.

Descendant's DNA helps identify lost sailor in doomed 1845 Franklin expedition by Global News

Descendant's DNA helps identify lost sailor in doomed 1845 Franklin expedition by Global News

2024 Discovery

In 2024, another major discovery happened when scientists figured out that some old remains belonged to Captain James Fitzjames, thanks to DNA from one of his living relatives. The bones revealed a grim story about the crew's last days, including signs of cannibalism.

FabTet, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

FabTet, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Identification Process

The identification process was made possible thanks to DNA testing done by members of the University of Waterloo and Lakehead University. Gregory's identification was a big deal because he was the first person from the Franklin Expedition to be recognized through DNA.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Wikimedia Commons

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Wikimedia Commons

Geographic Blunder

It looks like John Franklin's choice of route turned out to be a big mistake. He decided to go along the western side of King William Island. This side of King William Island is known for its harsh ice conditions, where ice tends to persist even throughout the summer months.

Maritim Greenwich Souvenir Guide, London 1993, Wikimedia Commons

Maritim Greenwich Souvenir Guide, London 1993, Wikimedia Commons

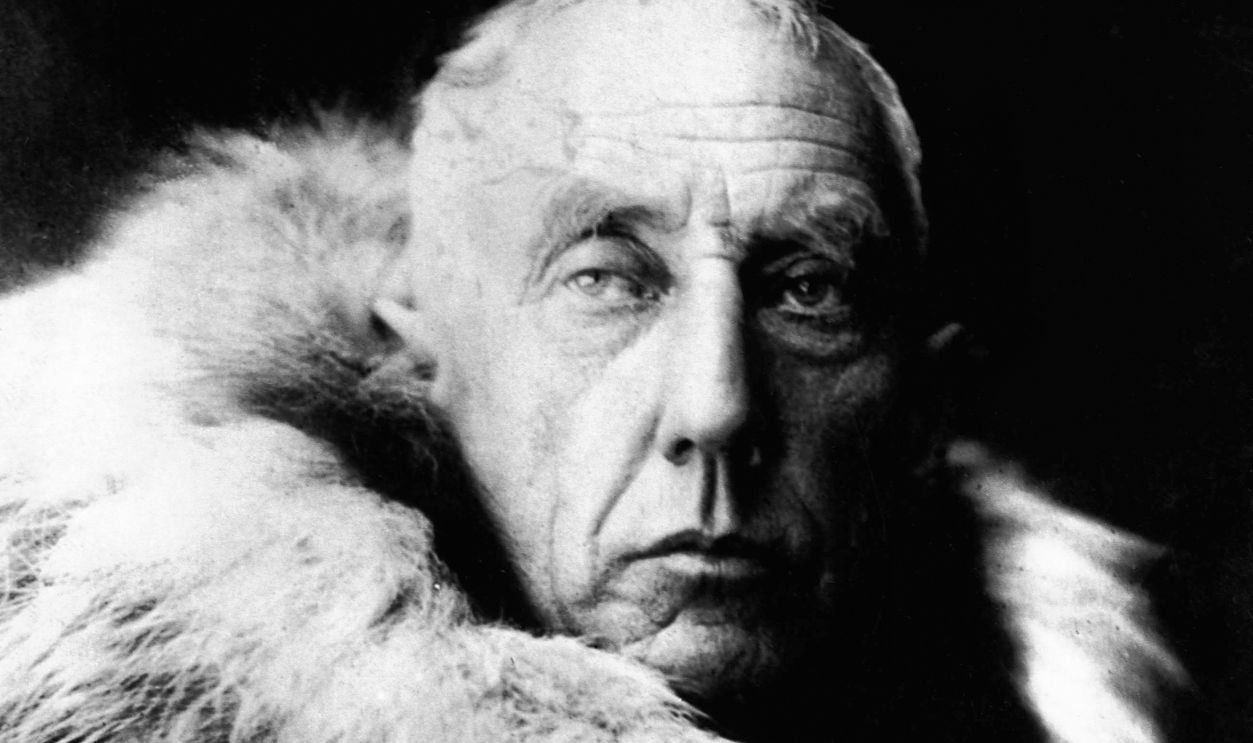

Expeditions Are More Than About Sailing

Hence, the eastern route, which Roald Amundsen successfully used in 1906, would have been a smarter option for getting through. Also, since the expedition was all about naval sailing, the crew missed out on essential land survival skills that were much needed.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Search Operations

Between 1848 and 1859, the British Admiralty set out on a bunch of search missions, sending out thirty-two ships to explore the Arctic. It was one of the biggest rescue efforts ever in naval history. Even though they couldn't find Franklin's crew, these missions did a lot for mapping the Arctic.

£675k-Worth Missions

They charted thousands of miles of coastline that nobody had seen before, providing important info about the region. All this cost around £675,000, which was a huge amount back then. At one point in 1850, eleven British and two American ships were conducting simultaneous searches.

Durand-Brager, Wikimedia Commons

Durand-Brager, Wikimedia Commons

Rescue Attempts' Legacy

The Franklin search missions changed the game for Arctic exploration, for real. When Robert McClure was out looking for Franklin and his crew in 1850–1854, he ended up discovering the first Northwest Passage. This happened even though his ship got stuck in the ice.

Stephen Pearce, Wikimedia Commons

Stephen Pearce, Wikimedia Commons

McClintock's Expedition

Then in 1859, McClintock's expedition found some important artifacts and the famous Victory Point note. All these search operations not only helped with Arctic navigation techniques but also led to better ice-resistant ship designs and new survival protocols for polar expeditions.

John Powles Cheyne, Wikimedia Commons

John Powles Cheyne, Wikimedia Commons

Archaeological Findings

The NgLj-2 site, which was found on King William Island in 1992, had information about what happened to the crew. Nearly 400 bones and bone fragments were found during excavations, along with personal things like brass buttons and clay pipes. This site matched McClintock's "boat place" description.

Stephen Trafton, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Stephen Trafton, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

A New Discovery

Robert McClure, while searching for Franklin in 1854, discovered the first navigable passage through the Prince of Wales Strait. In 1906, Roald Amundsen managed to be the first to successfully pass through the passage, using some of the insights he picked up from Franklin's expedition.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Beechey Island Camp

The first winter camp of the Franklin expedition at Beechey Island turned out to be quite interesting. Archaeologists have uncovered a bunch of food tins, many of which had shoddy lead soldering. There are still three graves present there today, if you may recall.

LawrieM, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

LawrieM, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Tried To Survive Against All Odds

These belong to John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine, with their bodies frozen in the permafrost. The site also had workshops, an observatory, and even a little garden—all signs that they were actually trying to set up a cozy winter base.

Gordon Leggett, Wikimedia Commons

Gordon Leggett, Wikimedia Commons

Beattie's Arctic Autopsies

In 1984, anthropologist Owen Beattie and his team got special permission to carry autopsies on the bodies found on Beechey Island. The frozen remains of John Torrington were surprisingly well preserved after 138 years, which caught media attention.

Owen Beattie and the sailor frozen in time by UniversityofAlberta

Owen Beattie and the sailor frozen in time by UniversityofAlberta

More Details

They also found that Hartnell's grave had been disturbed before; Edward Belcher had tried to dig him up back in 1852 but was stopped by the permafrost. Similarly, Braine's quick burial had an odd detail. His undershirt was put on backward.

Owen Beattie and the sailor frozen in time by UniversityofAlberta

Owen Beattie and the sailor frozen in time by UniversityofAlberta

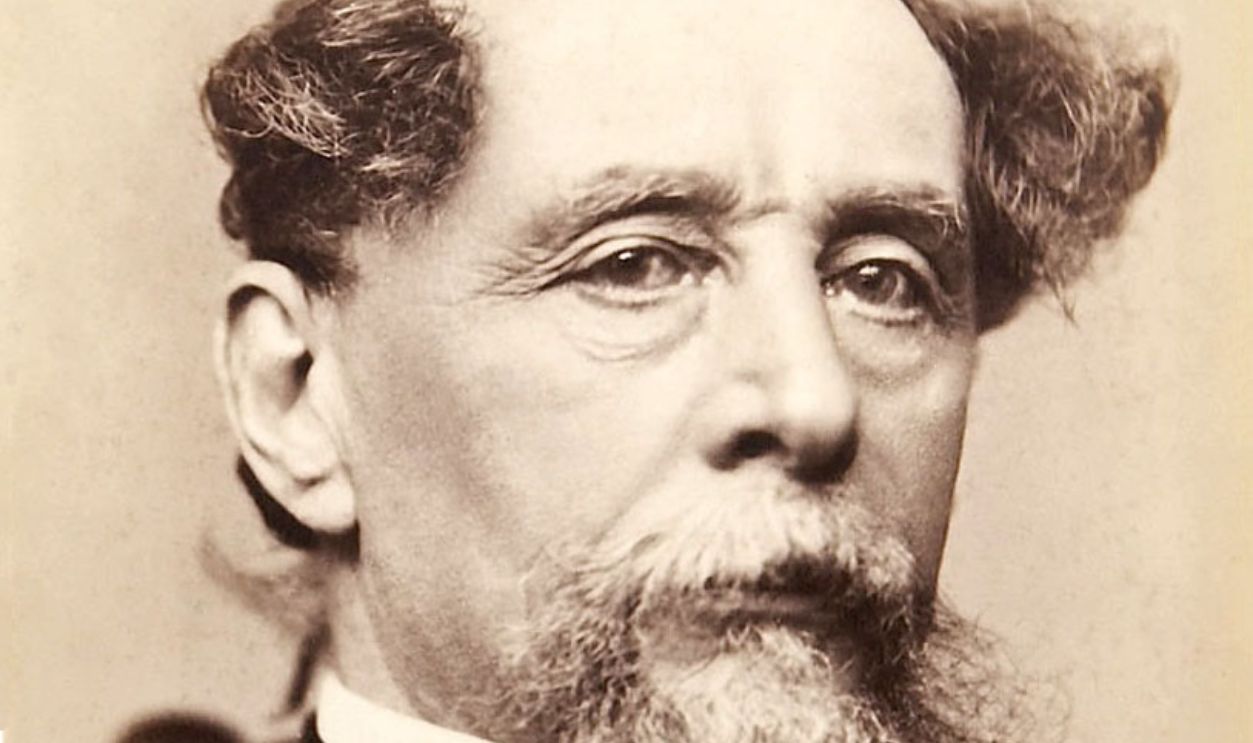

Cultural Impact

The Franklin expedition truly captured people's imaginations back in the day and still influences art today. The famous Charles Dickens even teamed up with Wilkie Collins to write a play called The Frozen Deep, which is presumed to be about this very expedition.

Chisties Auction House, Wikimedia Commons

Chisties Auction House, Wikimedia Commons

Tragedy Influences Art

Artists like Edwin Landseer made some striking paintings, especially "Man Proposes, God Disposes," which shows polar bears amidst the wreckage of the expedition. This tragedy has inspired tons of books, folk songs like "Lady Franklin's Lament," and modern stuff like AMC's show "The Terror".

Edwin Landseer, Wikimedia Commons

Edwin Landseer, Wikimedia Commons