Florence Nightingale requires little introduction to anyone who knows their medical history. The Victorian nurse’s name is a shorthand for first-class bedside care, and her social reforms changed the face of modern medicine both on and off the battlefield. Behind the legendary lamp, which she often carried to guide her way through field hospitals at night, what was this enigmatic woman really like? Find out with these 42 caring facts about Florence Nightingale, the Lady with the Lamp.

1. Brought Something Back from Vacation

Florence Nightingale was named after the city of her birth. Although her family was British, they welcomed Florence in the city of Florence, Italy. (It could have been worse; her older sister had been born in and named after the Greek settlement of Parthenope).

2. The School of Pops

Nightingale was born to a family of privilege and education. Both her upper-class parents were landowners educated in the liberal-humanities tradition. However, it was specifically her father, William Nightingale, who would be the future nurse's intellectual role model.

3. One of the Guy’s Girls

When she was 18 years old, Nightingale began her lifelong friendship with the writer and intellectual, Mary Clarke. Although Clarke was 27 years Nightingale’s senior, she influenced the young woman heavily with her masculine manners, eccentricity, and ambitious pursuits in the world of men.

Cypress Point Productions, Florence Nightingale (1985)

Cypress Point Productions, Florence Nightingale (1985)

4. The Ultimate Guidance Counsellor

The Nightingales deeply resisted Florence’s ambitions in nursing. In fact, her mother and sister were furious when she made her goals public in 1844. It didn’t matter to Florence: she saw her devotion to others as a calling from God Himself.

Augustus Egg, Wikimedia Commons

Augustus Egg, Wikimedia Commons

5. Care Comes in Many Tongues

Not only was Nightingale fluent in English, French, German, and Italian, she also had a good grasp on Latin and Greek too. From philosophy to mathematics and even Shakespearean literature, there were few intellectual matters that could daunt Florence Nightingale.

Charles Staal, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Staal, Wikimedia Commons

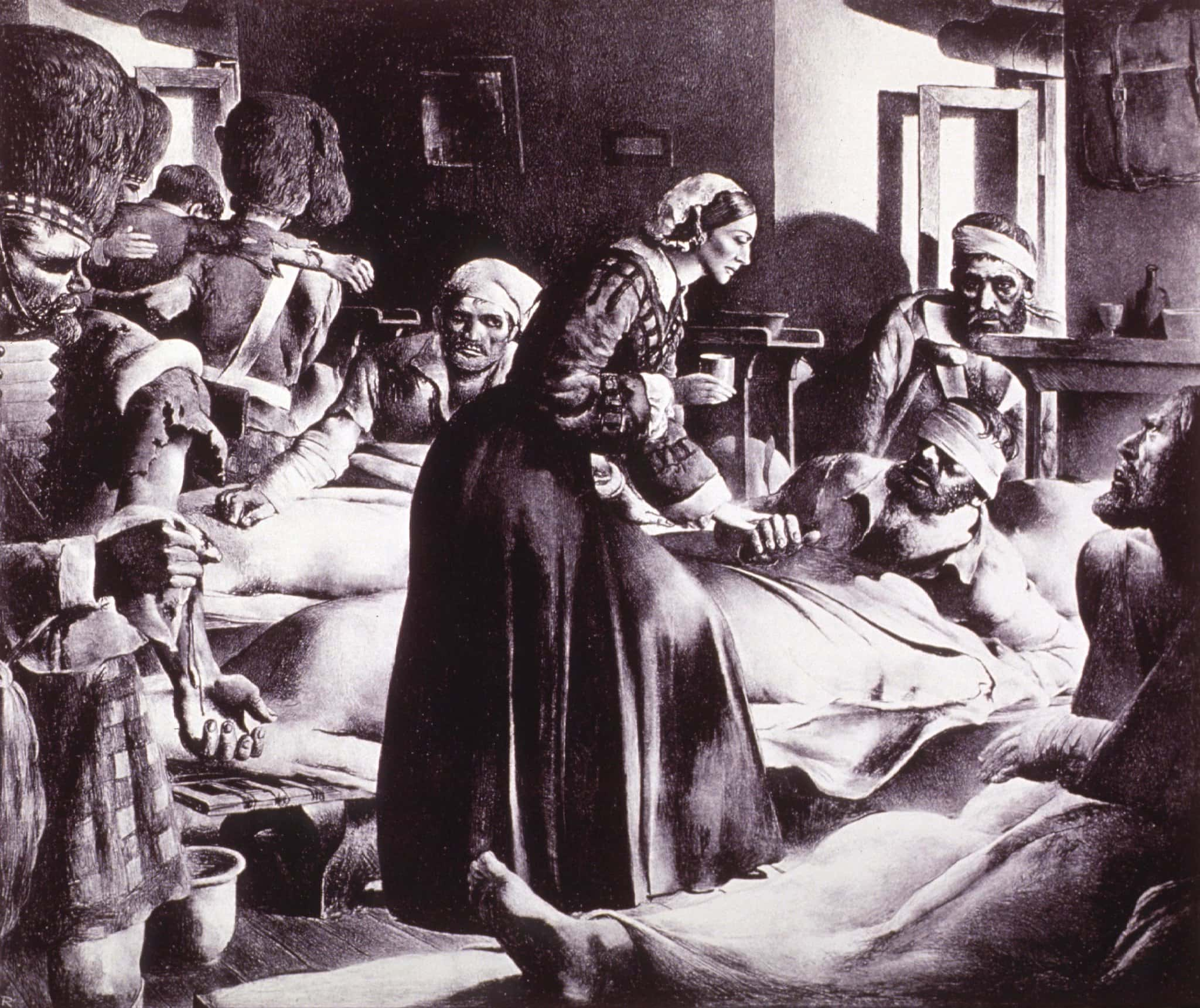

6. Not Today, Demise

Rat waste and the rodents themselves weren’t uncommon sights in Victorian conflict hospitals. Nightingale was able to deduce a then “radical” notion that lousy sanitation leads to demise. Leading a brigade of 38 other nurses, Nightingale led a cleanliness crusade through medical services during the 1850s Crimean Conflict. Thanks to her reforms—and the work of the nurses—mortality rates in the hospital where she worked dropped from 40% to just 2%.

Cypress Point Productions, Florence Nightingale (1985)

Cypress Point Productions, Florence Nightingale (1985)

7. A Bright Idea

Nightingale was known to the press as the “Lady with the Lamp” for her reputation as a “ministering angel” on the battlefield. A diligent nurse, she was often found checking on wounded army men throughout the night, lamp in hand, hence the glowing reputation.

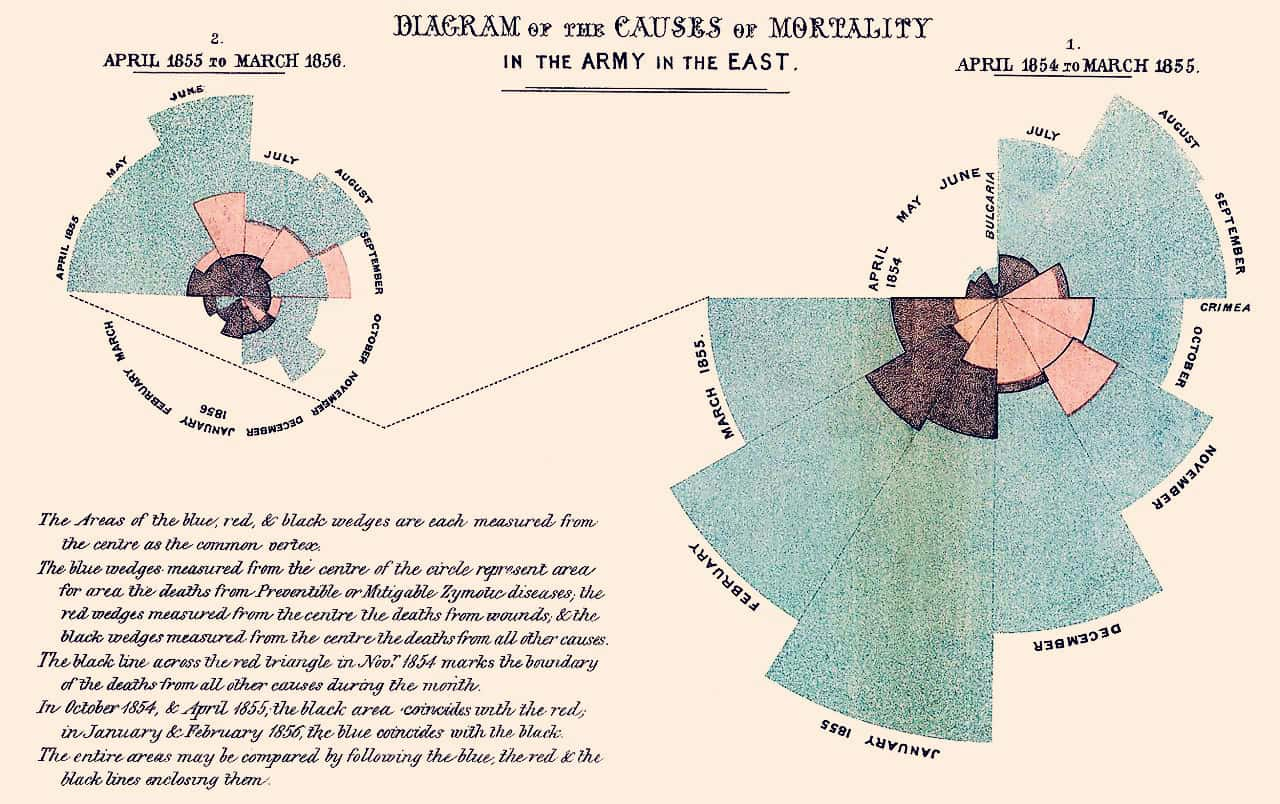

8. It’s As Easy As Pie

You like pie charts? Thank Florence Nightingale for popularizing the use of the infographics in journals and print culture. Although she didn’t invent the pie chart—they were first drawn in 1801, some 19 years before her birth—she was one the earliest adapters in her public medical reports. In her famous 1858 report, she used the chart to neatly show off the varieties and occurrence of conflict casualties, visualized in pie-form.

9. Her Majestic Fandom

Queen Victoria was a big-time Florence Nightingale groupie. She even sent the nurse a specially-made broach for her service, with a note that read "It will be a very great satisfaction to me, when you return at last to these shores, to make the acquaintance of one who has set so bright an example to our gender". The pair eventually met in 1856 and they stayed pen pals for the rest of their lives.

10. The Conflict at Home Will Save Lives

After the Crimean Conflict, Nightingale brought her sanitation crusade home. In the early 1870s, she heavily pushed for a policy that would make sure all English buildings had to connect to main drainage systems. If army men got clean water and conditions, why not citizens? The proof of Nightingale’s efforts lies in the numbers: by 1935, when the ambitious legislation had largely taken effect, the national life expectancy had shot up by approximately 20 years.

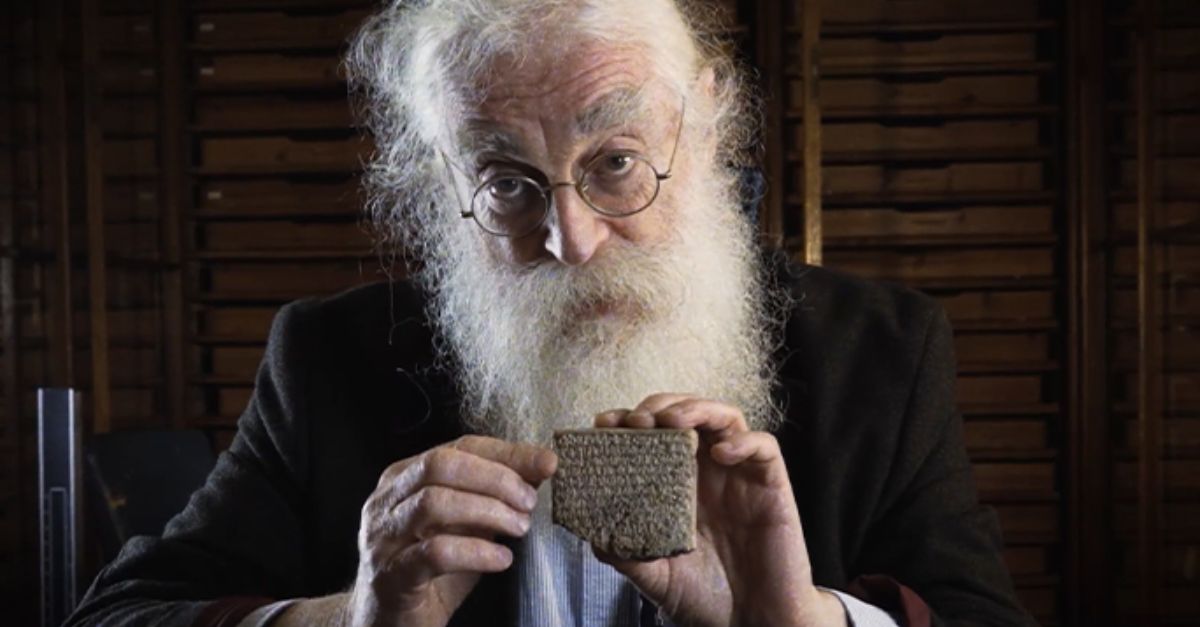

11. Flo’s Guide to Doing It All

In 1859, Nightingale published a book called Notes on Nursing: What It Is And What It Is Not. Spouting values from hand-washing to social discretion, it is still studied today.

Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome Images

Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome Images

12. United by the Nightingale

Both sides in the American Civil Conflict could agree on one thing: Florence Nightingale’s word—at least when it came to hospital ventilation—was law. Both factions designed their hospitals in accordance to her now-published standards. However, she chose her own side and helped the Union army take inventory of their mortality numbers.

13. The Next Generation

American nursing also owes a lot to Florence Nightingale. Linda Richards, or “America’s First Trained Nurse,” as she became known, was educated at London’s Nightingale School of Nursing under the Lady with the Lamp herself.

14. Admitted on Merit

Florence Nightingale was the first woman to be inducted into the British Order of Merit. Awarded the honor by Edward VII in 1907, she would be the first and only woman for a long time—it was 58 more years until another was invited to the order.

15. Healthy Anniversary

Since 1974, we celebrate May 12 as International Nurse’s Day. Not so coincidentally, this is also Nightingale’s birthday.

16. Subscribe to My Soundcloud

Want to hear her voice? Go to YouTube and enjoy Nightingale's brief audio recording with Thomas Edison, where she promoted further support for Crimean Conflict veterans: "When I am no longer even a memory, just a name, I hope my voice may perpetuate the great work of my life. God bless my dear old comrades of Balaclava and bring them safe to shore. Florence Nightingale".

17. Poetry is the Best Medicine

Nightingale is the inspiration for Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, “Santa Filomena". The work features a wounded man who sees a “lady with a lamp” as he lays in a field hospital.

Getty Images

Getty Images

18. She’s the Man

Nightingale sometimes referred to herself as a man. Specifically, she would call herself “a man of action” or “man of business,” as the context required.

Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome Images

Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome Images

19. Too Busy to Be Sexy?

As is the case with many powerful women, Nightingale’s chastity (or lack thereof…) remains a much-debated topic among modern historians. There is a strong school of thought which believes she was celibate all her life due to both religious and career reasons.

20. To Serve and Disinfect

Florence Nightingale was the first recipient of the Royal Red Cross. Established by Queen Victoria in 1883, it was created specifically to honor army nursing.

21. Right in the Family Jewels

Remember that broach she got from Queen Victoria for her service? Yeah, it was known as the “Nightingale Jewel,” and came with a $250,000 grant from the government. At this point, you know she kept doing her good work for love, not money.

22. Pay It Forward, Flo

After becoming rich from a $250K prize, Nightingale donated it all to help build St. Thomas' Hospital, as well as the Nightingale Training School for Nurses.

23. Reading Pain-bow

Nightingale used Basic English to write her medical books and reports. Paired with her use of readable infographics, she was instrumental in making health knowledge accessible, even for those with low-level literacy.

Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome Images

Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome Images

24. Jacqueline of All Trades

Over the course of her life, Nightingale wrote about 200 books, articles and pamphlets—and only some of these were related to medical professionalism. She was also interested in social writing, religious treatises, and even engaged with Roman mythology.

25. RN of the Thinkpiece

Florence Nightingale wrote “Cassandra,” a Victorian feminist polemic that lambasted society for socializing women to be weak. She cites how her mother and sister fell into “lethargy,” even with their good education. She also discloses her fears that she might become like the mythical Cassandra, a princess of Troy cursed with foresight that no one believes.

26. Collect Those Air Miles and Those Health Points

Nightingale is also the mother of medical tourism. Influenced by her own privileged youth of travels, she encouraged patients to travel out as far as necessary for cheaper medicines and standards of living.

27. I’d Rather Chill at Home

For her lifetime of service, Nightingale was given the chance to be buried in Westminster Abbey, among the United Kingdom’s most elite figures. Her family turned them down, opting for Nightingale to be buried in their family plot at St. Margaret’s Church. Mind you, this was Nightingale’s own dying request.

28. Power Nap

After a lifetime of battlefield nursing, Florence Nightingale passed peacefully in her sleep on August 12, 1910. She had lived to the ripe age of 90.

Jack1956, CC BY-SA 4.0 , Wikimedia Commons

Jack1956, CC BY-SA 4.0 , Wikimedia Commons

29. Not Like Magic, But Close

Nightingale was a fan of medieval mysticism. She translated several medieval mystic words, believing they brought her work closer to God. Most of these more “eccentric” writings were only published after her demise.

30. Good Living for All

Nightingale was an advocate for hunger relief and street workers’ health in India. In the 1860s, the British government tried to introduce a law that would force female street workers to receive medical examinations by the state—with no mandatory testing for men, of course. Although she held generally anti-gender work views, Nightingale still fought against this legislation. From her research, she saw it as unfair—and also just plain ineffective in preventing the spread of venerable disease.

In her formal analysis, she saw the bill as informed by a double standard that had little medical basis. Instead, she and other opponents of the bill saw health as determined by social factors like poverty and diet, rather than ideas of gender and purity. Nevertheless, she only succeeded in getting the bill’s passing slowed down, not abolished.

31. A Call From Upstairs

While in Cairo, Nightingale wrote about being “called to God” for a higher purpose. “God called me in the morning and asked me would I do good for him alone without reputation". She later visited a German community where she saw a pastor and deaconess heal the sick. She put two and two together, and Nurse Nightingale was born again.

32. Early to Nurse, Early to Rise

Just three years into volunteering as a nurse, Nightingale was promoted to superintendent of a London hospital. After finishing her nursing studies abroad in Germany, she returned to London and worked in a hospital specifically for governesses. There, the young woman impressed her superiors with her dedication to this oft-thankless profession.

33. Daddy Big Bucks

Nightingale could only pursue her philanthropic nursing efforts with financial help from her father. Throughout her career, she was given an annual allowance of £500, which is about £40,000 in today’s money. As it often goes, no one does it alone.

34. The Pen Cuts Mightier Than the Scalpel

Nightingale’s robust education in words paid off in a grim way. She often took it upon herself to write eloquent letters back home to the families of gone or dying army men. In one of these letters, she delicately wrote, “It is with very sincere sorrow that I am obliged to confirm the fears of the father of the Late Howell Evans about his poor son…I have never in my life had so painful & unsatisfactory a letter to write". Now imagine having to bear that bad news some hundred times.

35. You Can’t Have It All

Most agreed that the young Florence Nightingale was pretty, slender, and charming. The poet and statesman Richard Monckton Milnes was among the most ardent suitors for her hand, and he courted her for nine long years. But alas, it was for naught—Florence broke it off because wifely duties would get in the way of her true calling as a nurse.

36. Time for an Upgrade

Nightingale's family, especially her mother and sister, never supported her decision to go into nursing—though, to be fair, they were right to wish “better” for her than nursing. In early Victorian England, nursing was rampant with alcoholism and low wages. It wasn’t unheard of for nurses to make ends meet with adult street work. These days, Nightingale is heavily credited for bringing “respectability” to the profession.

37. Nursed to End?

In 1861, Nightingale was accused of ending a statesman with cleanliness. Or rather, people whispered that her pressure for healthcare reform sent Sidney Herbert to an early grave…though his case of Bright’s Disease certainly helped.

38. Partner in Arms

Despite her “implication” in his end , Sidney Herbert was good friends with Nightingale, whom he met on his honeymoon in Rome. He would be Secretary of Conflict on two separate occasions, during which Nightingale served as a close political advisor.

39. Who Nurses the Nurse?

Nightingale never fully recovered from a bacterial infection that she contracted during the Crimean Conflict. While crusading for cleaner hospitals, she herself became almost fatally sick with Crimean Fever. For the rest of her life, she suffered from reoccurring symptoms, but she kept it fairly hidden in order to pursue her work.

40. It’s Not in Your Head

Partly related to her long-term battle with illness, Nightingale suffered from long-term depression. Her struggles with mental illness affected her writing such that she produced much less in the final decade of her life.

41. Slow Down, Ladies

Despite her personal strength and engagement with feminist literature, Nightingale didn’t agree with all women’s rights activists. She couldn’t get why ladies kept fighting for more career options when the nursing profession was right there—and always short on workers. In general, she agreed with the historically conventional view that women weren’t as equipped as men when it came to most jobs and claimed that many women's rights activists were simply looking for "sympathy".

42. Gentlemen First

Although she had several long-lasting and loving female friendships, Nightingale preferred the company of men overall. In particular, she liked powerful and intellectual fellows, whom she saw as doing more to advance her career than any woman she had met. To quote Nightingale: “I have never found one woman who has altered her life by one iota for me or my opinions". Now, who knows what she would have said if women had had the opportunity…

Cypress Point Productions, Florence Nightingale (1985)

Cypress Point Productions, Florence Nightingale (1985)