Who Are The Abenaki?

The Abenaki are Indigenous people of North America who were once nomadic hunter-gatherers. They spent years living peacefully off the land before European settlers arrived and forcefully took over their territory.

After a long and courageous battle, the Abenaki were on the verge of extinction—and are still fighting today to save their culture. This is their story.

Where Do They Live?

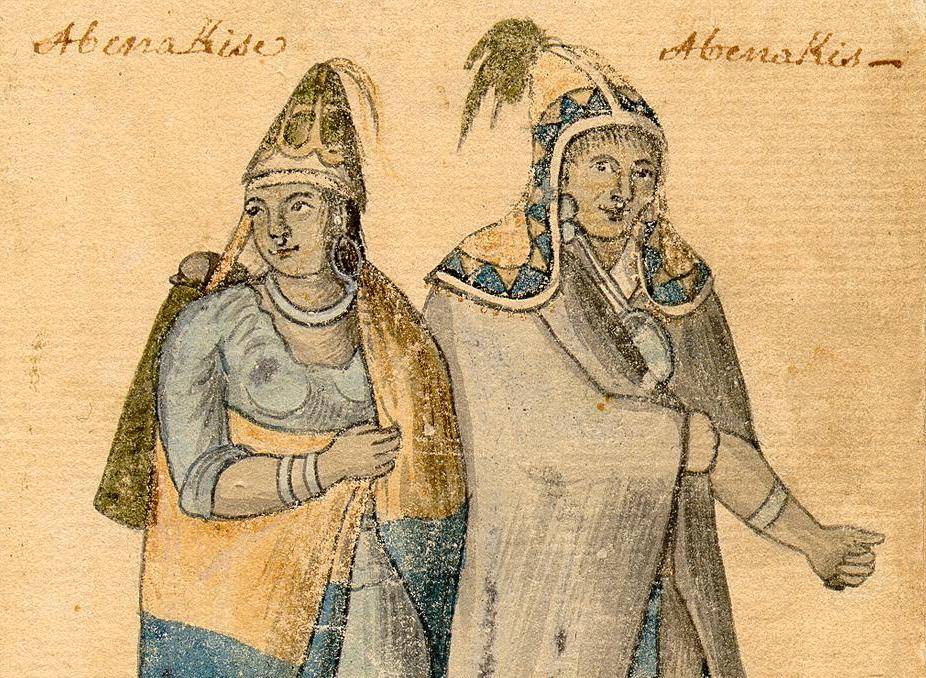

The Abenaki live in the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. Their traditional homelands included parts of southern Quebec, western Maine, and northern New England.

Today, there are two Abenaki reserves in Quebec, Canada: the Abenaki of Wôlinak, and Odanak—combined, they have a registered population of just over 3,800. Some people live on the reserve while others live in cities and towns across the US and Canada.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Which Confederacy Do They Belong To?

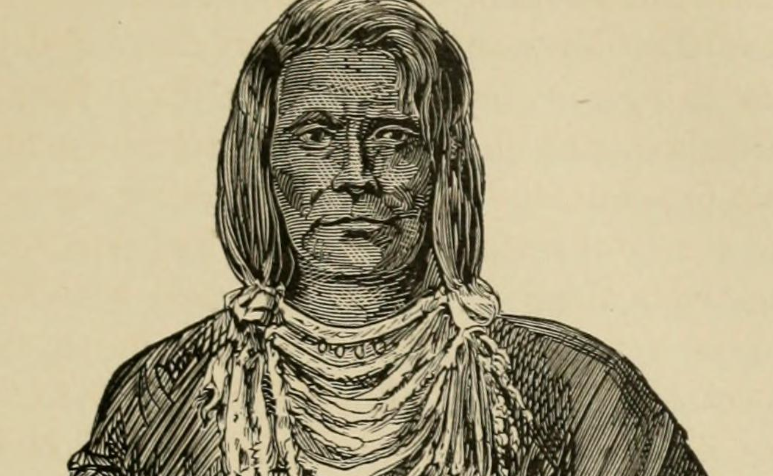

The Wabanaki Confederacy emerged in the 17th century as a response to threats imposed by the Iroquois Confederacy—who were known for their raiding and warfare.

The creation of the Wabanaki Confederacy was to provide a united front for defense, and it included the Abenaki, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), and Mi'kmaq.

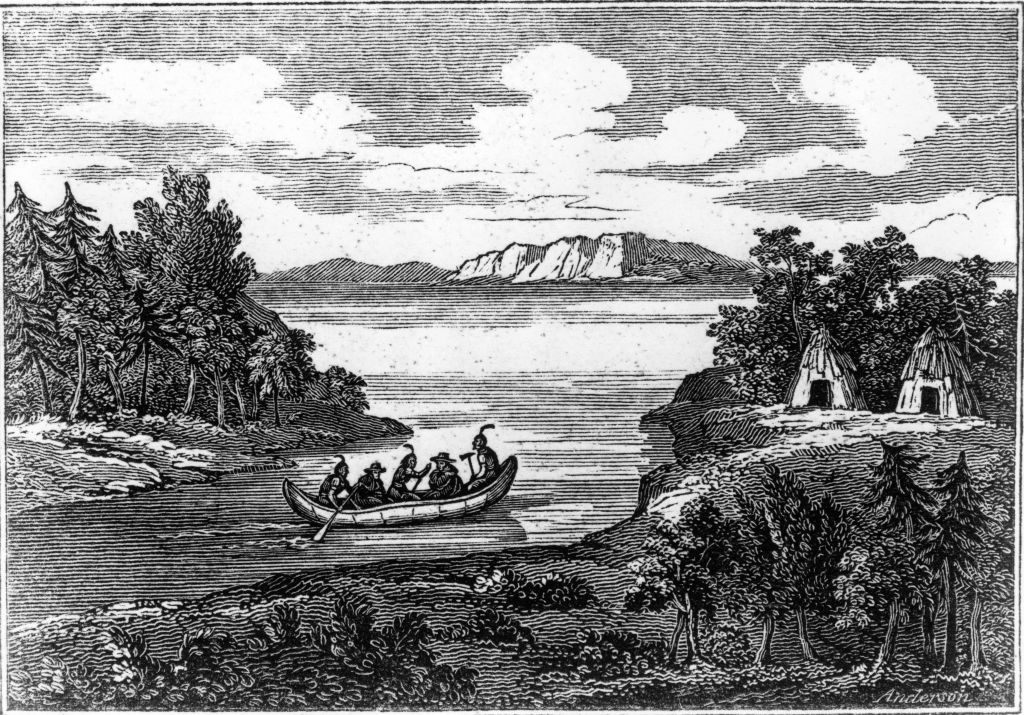

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

What Language Do They Speak?

The Abenaki language, also known as Wôbanakiak, is an endangered Eastern Algonquian language. It has both Eastern and Western forms which differ in vocabulary and phonology—and are often considered separate languages.

Even with revitalization efforts over the years, the languages are phasing out as younger generations fail to learn their native tongue. Today, the Western Abenaki language is almost entirely extinct.

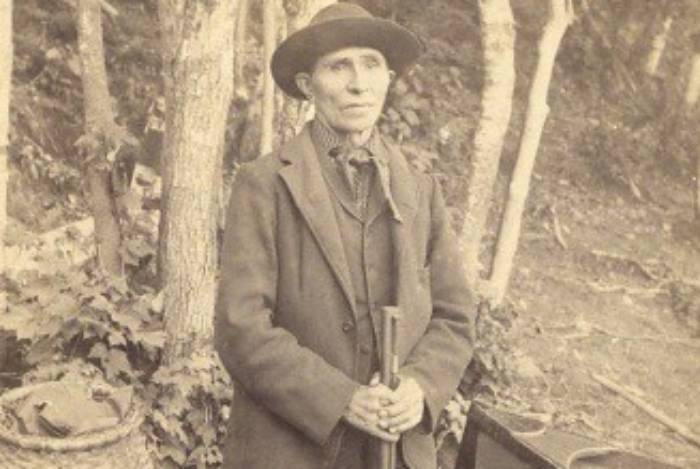

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

What Does Their Name Mean?

The word Abenaki is taken from Wabanaki, or Wôbanakiak, which means “People of the Dawn Land”. But they also sometimes call themselves Alnôbak, meaning “Real People”.

Ethnologists classify the Abenaki by geographic groups: Western Abenaki and Eastern Abenaki—which are also made up of several individual bands.

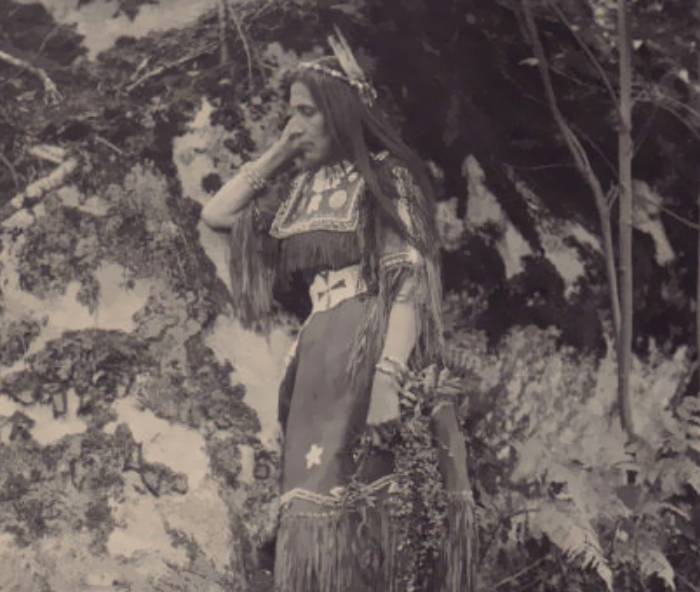

Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, Picryl

Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, Picryl

What Is Their Lifestyle Like?

Before the English swooped in and colonized their lands, the Abenaki practiced a subsistence economy—having only what they needed. They were excellent hunters, fishermen, and trappers. They gathered berries and grew crops, and made their own necessities.

And while they were mostly a farming community, they also had to be somewhat nomadic—moving around with the seasons based on availability of resources.

The German Kali Works, Wikimedia Commons

The German Kali Works, Wikimedia Commons

What Did They Eat?

The Abenaki ate a wide variety of food provided by their lush environment. They hunted small game, ate a variety of fish, gathered wild plants, and grew crops such as corn, beans, squash, potatoes—and even tobacco.

They also had a sweet tooth for wild berries and maple syrup.

The German Kali Works, Wikimedia Commons

The German Kali Works, Wikimedia Commons

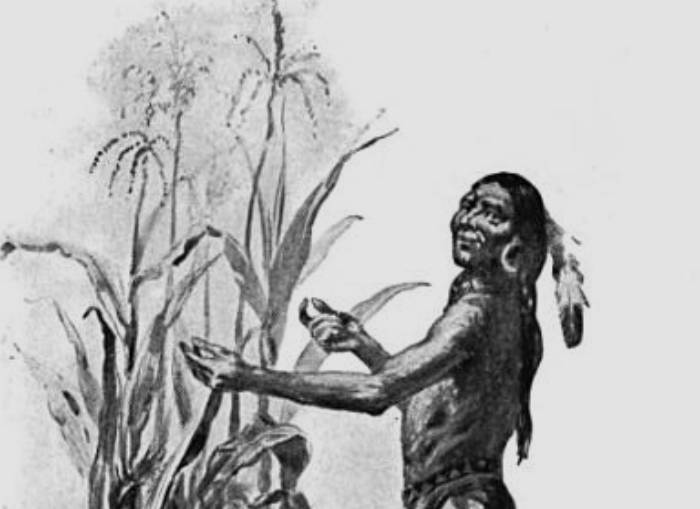

How Did They Farm?

The Abenaki were primarily a farming society (in the summer months) that supplemented agriculture with hunting and gathering. Generally, the women tended the fields and grew the crops.

They planted their crops in groups known as the “three sisters”: corn, beans, and squash. The stalk of corn supported the beans, and the squash or pumpkins gave them ground cover and reduced the weeds.

Portland Press Herald, Getty Images

Portland Press Herald, Getty Images

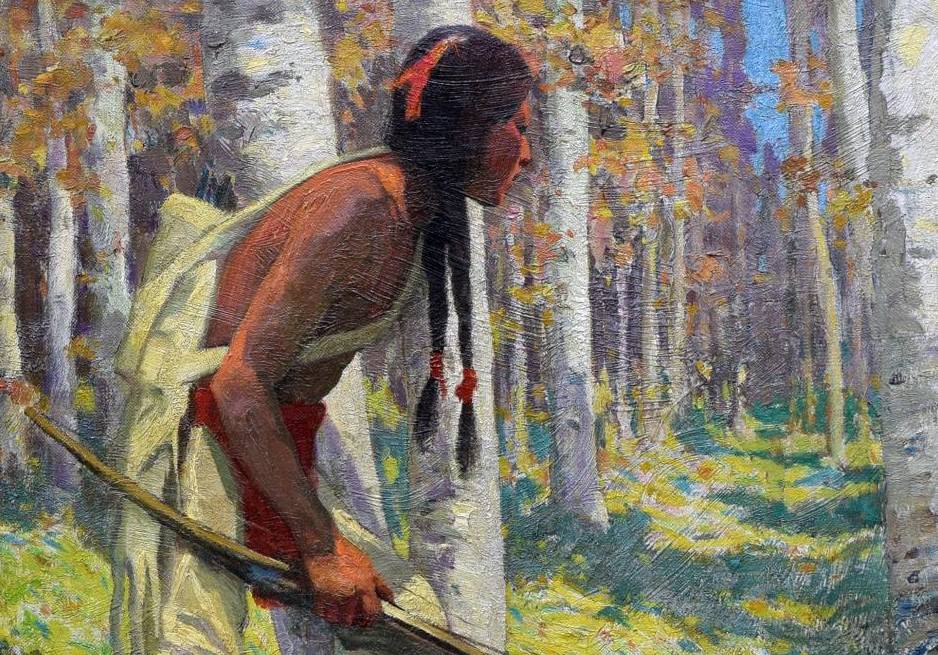

How Did They Hunt?

The men were generally the hunters. Each man had different hunting territories that he inherited through his father. Traditionally, men would leave the village for several days at a time to go hunting.

And they had a variety of ingenious hunting tactics.

E. Irving Couse, Wikimedia Commons

E. Irving Couse, Wikimedia Commons

Hunting Tactics

The Abenaki hunted and trapped a variety of animals, big and small. For larger game, the Abenaki hunters baited trap lines and strung them for miles. They also used knives, bows and arrows, spears, snares, pitfall traps, and the kelahigan (or deadfall trap)—where a heavy log is dropped on the animal as it tries to snatch the bait, crushing its skull.

They were intelligent hunters. Not only did they know their environment well, they knew their prey, too.

Hunting Tactics

Another ingenious hunting method the Abenaki practiced involved lighting a fire and burning brush to drive deer and other game into funnel-shaped enclosures where hunters lay in wait. The animals would then be snared or shot with arrows as they passed through.

They knew the behaviors of their prey, and often invited them into their lands, making it easier to hunt them.

Matheüa Merian (1592-1650), Wikimedia Commons

Matheüa Merian (1592-1650), Wikimedia Commons

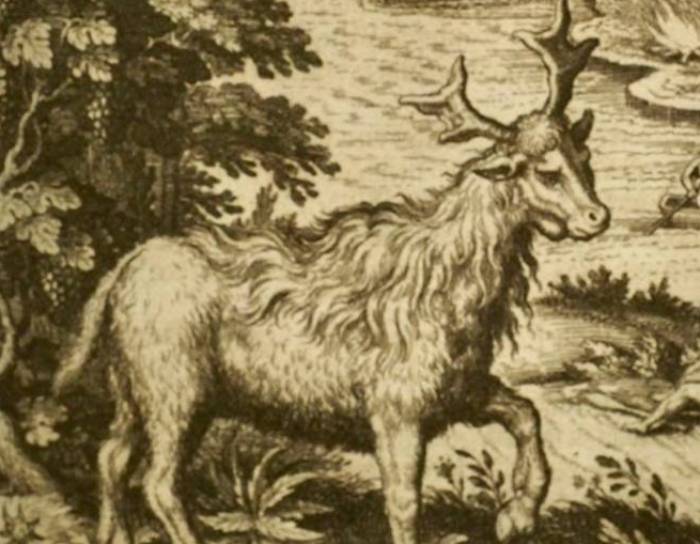

How Did They Attract Wildlife?

The Abenaki were so well attuned to their environment that they knew just how to use it to their advantage. By observing their prey, they learned that deer, elk, cottontail, and other small animals would often gather in the forest’s clearings—patches of land that were created when trees came down in a storm, or were burned by a fire.

And so, the Abenaki started doing this on purpose. Burning the land would encourage new growth, and the animals would come to munch on the sprouts. By sharing the land with their prey, the Abenaki didn’t have to go far to hunt.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Picryl

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Picryl

What Were Their Villages Like?

Traditional Abenaki villages were always built close to a water source. Their homes, called wigwams, were built in a half-circle pattern, with a fire pit in the center. Crops were planted around the edges of the village.

Edward S. Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

Edward S. Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

How Many People Lived In Each Village?

During the cooler months, and especially the harsh winters, Abenaki lived further inland, in smaller dispersed bands of extended families. These bands would then come together in spring and summer at seasonal villages—usually located near fertile riverbeds that maximized summer farming.

Some of these summer villages were fairly large, with hundreds of people coming together.

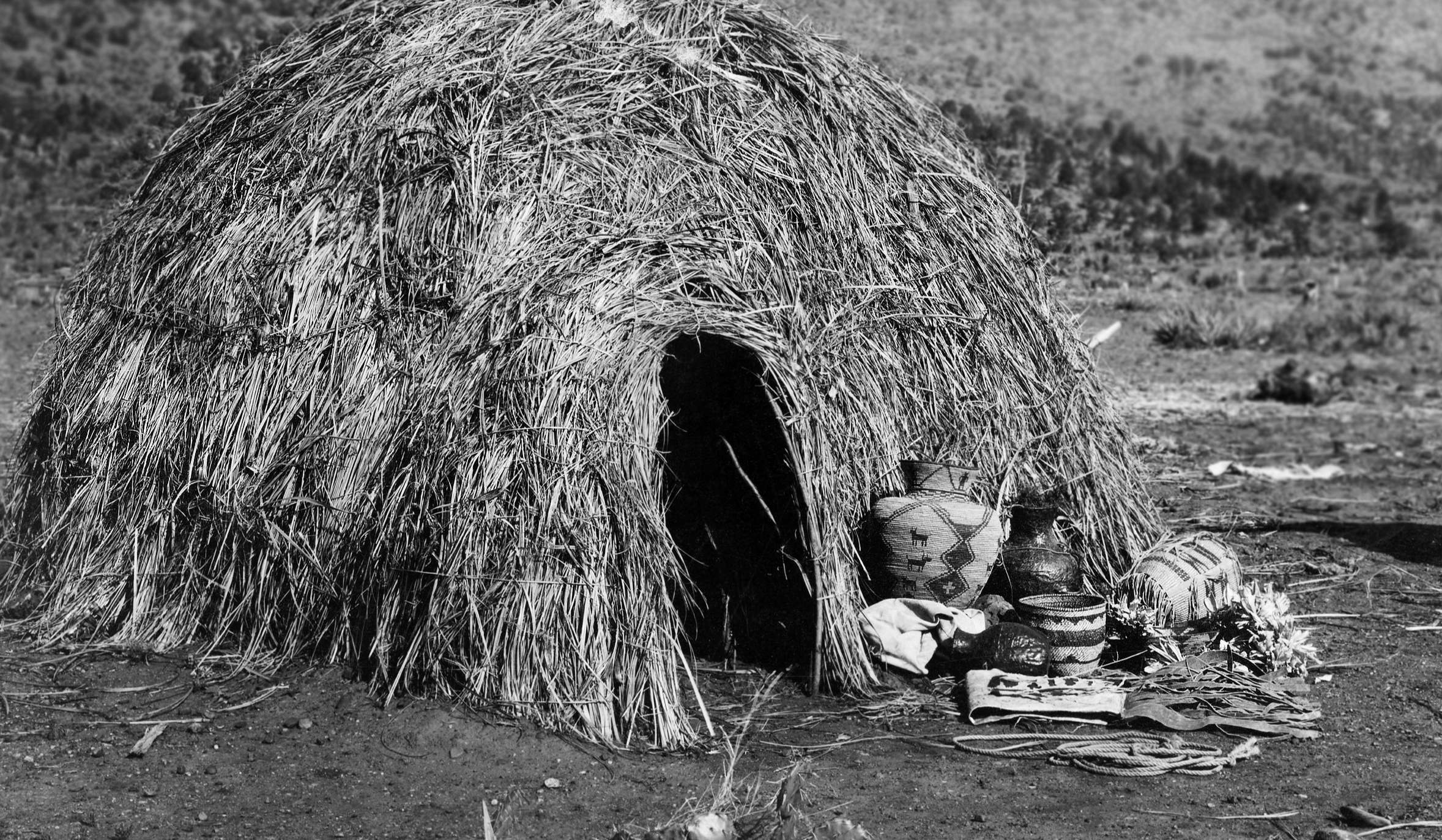

What Were Their Houses Like?

Traditionally, the Abenaki lived in wigwams, which were small cone-shaped domes made using branches, birch bark, and animal hide. They were about 8-10 feet tall and fit 4-6 people. When Abenaki traveled to hunt or fish, they would take these shelters with them, or build similar, travel-sized versions.

Wigwams were primarily used for sleeping, and as refuge from bad weather. The Abenaki spent most of their time outside.

But they also had more permanent structures.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

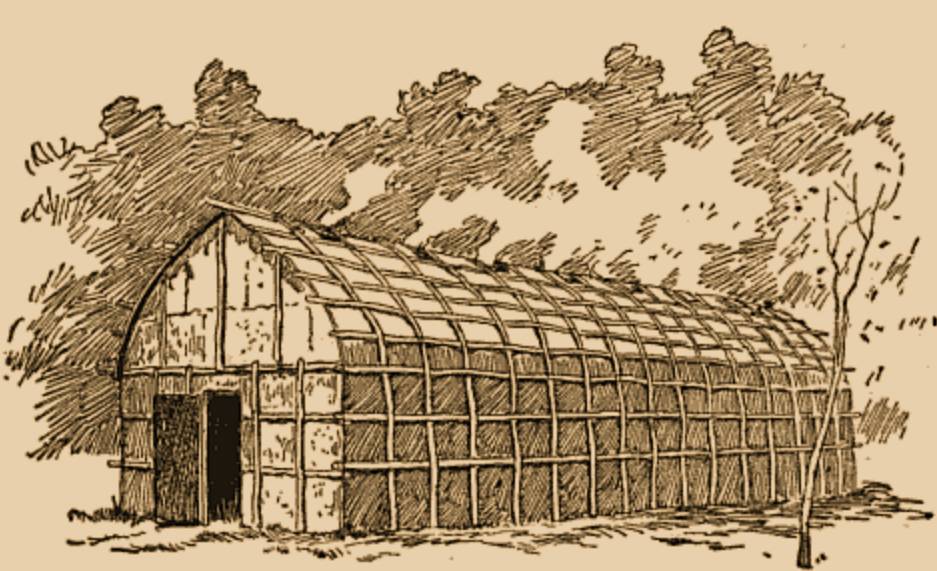

What Were Longhouses Used For?

Each village had a few larger, more permanent structures called longhouses. They were made using wooden poles and strips of bark. Longhouses were typically used for community gatherings and ceremonies, however, in the winter months, some families would group together in a longhouse for added warmth. Unmarried young men may also live together in a longhouse when not hunting or fishing.

All of their structures were made in ways that allowed small fires inside for warmth in the winter months.

Wilbur F. Gordy, Wikimedia Commons

Wilbur F. Gordy, Wikimedia Commons

What Other Supplies Did They Have?

Traditionally, the Abenaki used their natural resources to handmake their own necessities. As we know, animal hide and branches were used to make shelters, but they also used animal hide for bedding, clothing, or anything else that would typically require a material of some sort.

They also made canoes carved out of trees, snowshoes, storage containers, and even whistles, using a variety of their forested resources.

Paul VanDerWerf, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Paul VanDerWerf, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

What Craft Are They Known Best For?

The Abenaki were—and still are—excellent basket makers. Using ash and sweet grass, baskets of all shapes and sizes were regularly used for a number of reasons.

Basket weaving continues to be a traditional activity practiced by tribal members today.

Nebi: Abenaki Ways of Knowing Water, Made Here - from Vermont Public

Nebi: Abenaki Ways of Knowing Water, Made Here - from Vermont Public

What Did They Use Plants For?

Considering their natural surroundings were their only resources, they certainly used it well. Wild plants were in abundance in their territory, and they found many excellent uses for them.

Many wild plants were used as tea, soup, jelly, sweetener, a condiment, snack, or even as full meals.

But their most important use is still widely practiced today.

What Are Wild Plants' Most Important Use?

Aside from consuming wild plants for sustenance, they were their medicine. From headaches, colds and fevers, to pain and gastrointestinal ailments, there was a natural remedy at their feet.

Certain plants were known to be disinfectants, some were a cure-all for respiratory aid, and others were used as sedatives, pain relief, and for various other ailments. The Abenaki even had specific plants for teething children. Certain plant gums were used to make lotions for itching—the remedies are endless.

Many Abenaki today still swear by their natural remedies.

University of Washington Library digital collections, Picryl

University of Washington Library digital collections, Picryl

How Do They Keep Their Traditions Alive?

Storytelling has always been a major part of Abenaki culture. Aside from entertainment, storytelling is the Abenaki’s number one teaching method—especially when it comes to behavior. Abenaki did not mistreat their children. So, instead of punishing the child, they would be told a story.

They view stories as having lives of their own. One particular story is of Azban the Racoon, who learns of pride.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Picryl

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Picryl

Azban The Racoon

In this story, a proud racoon challenges a waterfall to a shouting contest. When the waterfall does not respond, Azban dives into the waterfall to try to outshout it—but gets swept away because of his pride.

This story would be told to teach a child about pride. There are stories for nearly everything, and everyone—young or old. Storytelling continues to be another traditional practice that is still widely used today.

The most important stories told, though, are those of perseverance and resilience—an integral part of Abenaki history.

Gunawan Kartapranata, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Gunawan Kartapranata, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

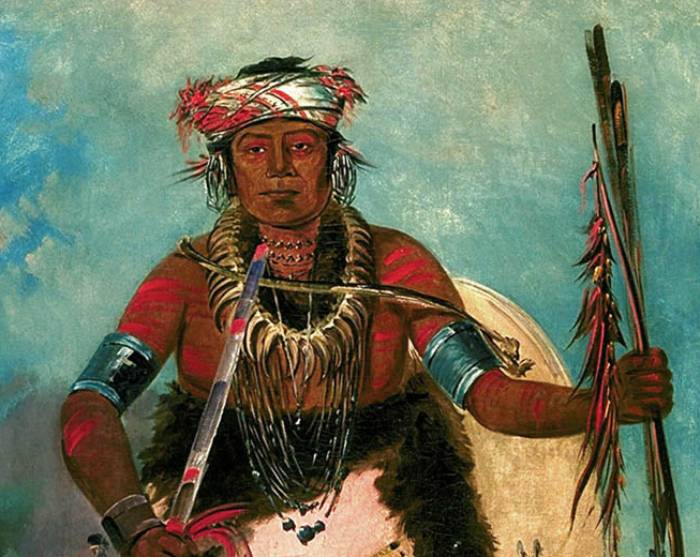

What Is The Most Important Part Of Abenaki History?

While the Europeans' arrival is especially important, it is also good to note that prior to colonization, the Abenaki still had enemies—they just came in the form of neighbors.

Pre-colonial Iroquois were their main fight. The Iroquois were large and powerful, and they were good at taking over land that they felt entitled to, especially when it came to their agriculture.

But the Abenaki were not just skilled hunters—they were also excellent warriors.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Why Did They Fight Against The Iroquois?

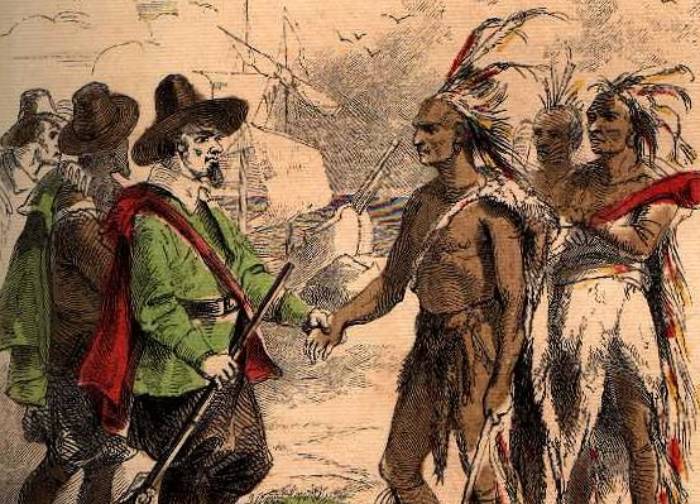

The Abenaki were often in conflict with the Iroquois over hunting grounds and the fur trade, which led to tribal wars and unfortunate territorial losses for the Abenaki. But things were kicked up a notch when the Europeans arrived.

Bows and arrows were no longer their worst fear.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

What Did The Europeans Bring?

During the 16th century, Europeans had made their way across the North Atlantic to access the prime fishing spots on the Grand Banks. While initial contact wasn’t always violent, the contact alone introduced a new threat—one so dangerous it was known to clear out Indigenous populations in record speed.

Le Tour du monde, Wikimedia Commons

Le Tour du monde, Wikimedia Commons

What Was This New Threat?

Contact with Europeans often exposed Indigenous populations to Old World diseases—for which they had no immunity. Before contact, it is estimated that the Abenaki had a population close to 40,000.

But as soon as the Europeans arrived, two major epidemics occurred. The first was an unknown virus that decimated Indigenous populations between 1564 and 1570.

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Which Epidemics Wiped Out Their Population?

The second epidemic arrived in 1586, and it brought typhus fever to the Abenaki—wiping them out in large numbers. But it only got worse in the early 1600s when two different illnesses swept across New England and the Canadian Maritimes with a tremendously high fatality rate of 75%.

As a result, the Abenaki population fell to a mere 5,000—and it wasn’t over yet.

How Fast Were They Declining?

After European colonization in Massachusetts in 1620, the epidemics got worse. Smallpox made its rounds several times over the next few decades, along with influenza, diphtheria, and measles, taking the Abenaki out fast.

At the same time, various tribes in the area were now at war with the Europeans, who traveled across the ocean to settle on new land—their land.

How Did The Abenaki Raise Their Numbers?

During this time, the Abenaki population was in a serious decline, so they started taking in thousands of refugees from southern New England tribes who were displaced by the wars.

In 1669, as a result of the disease and conflict, the Abenaki started to flee to Quebec, looking for refuge—but their troubles were far from over.

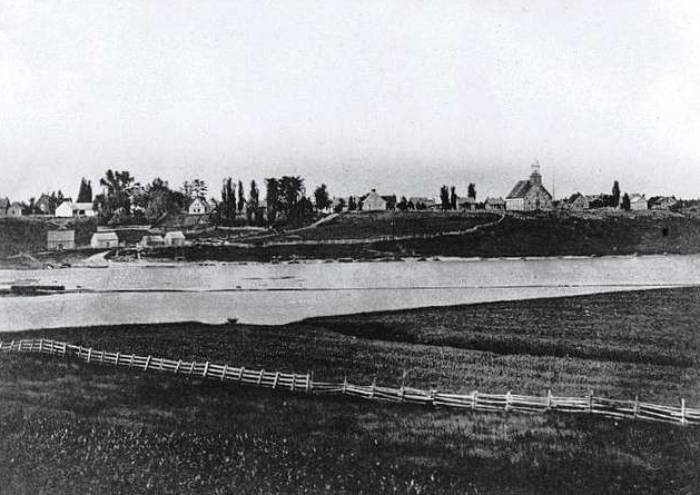

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Joining The War

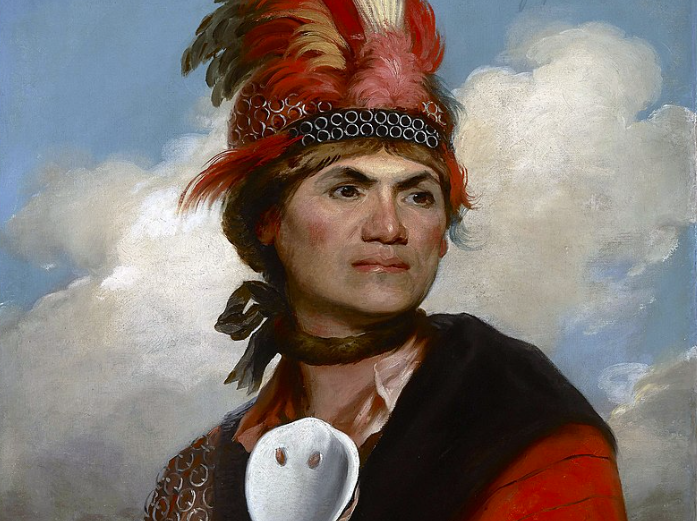

In 1675, the Wampanoag under Chief Metacomet—who adopted the English name, King Philip—fought the English colonists in New England, and the Abenaki joined.

For three years, they fought along the Maine frontier in the First Abenaki War—and it was absolutely brutal.

Paul Revere, Wikimedia Commons

Paul Revere, Wikimedia Commons

The First Abenaki War

The First Abenaki War was a brutal one. The Abenaki pushed back against White settlements through devastating raids on their farmlands and villages. But as tough as they were, the Abenaki were completely outnumbered. The war resulted in a peace treaty in 1678—but the Wampanoag were decimated. Any Native survivors were sold into slavery in Bermuda.

Their next big war wasn’t too long later, but this time they made an alliance.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Queen Anne’s War

In 1702, the Abenaki were allied with the French in the Queen Anne’s War. This war was primarily fought between Great Britain, France, and Spain—who all wanted territory in North America.

This time, the Abenaki stood a better chance. Along with their French allies, they raided numerous English colonies in Maine, and some in Massachusetts, taking the lives of over 300 settlers over the course of 10 years.

Some captives were adopted into the Abenaki and Mohawk tribes, others were ransomed or traded. But while this conflict may have been somewhat victorious—it was far from over.

Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

Third Abenaki War

The Third Abenaki War was next, and it lasted a few years, between 1722-1725. It was often called the Drummer’s War or Father Rale’s War. This conflict erupted when a French Jesuit missionary named Sébastien Rale encouraged the Abenaki to put a stop to White settlements. But when the Massachusetts militia tried to capture Rale, the Abenaki went full force and raided multiple White settlements—causing the Massachusetts government to officially declare war.

Bloody battles ensued until eventually Rale was killed and the Abenaki relocated—with a serious hit to their population.

Thomas W. Strong, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas W. Strong, Wikimedia Commons

A Division Of Loyalty

Not long after the Abenaki settled in Quebec, they were sharpening their spears once again. This time, Abenaki warriors were divided. Since they had previously allied with the French, some bands had now sided with the Americans—who were still encroaching on their lands—while other bands sided with the British, due to pre-existing alliances regarding territories and trade routes.

But this division caused serious grief.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

The American Revolution

Over the next several years, Eastern Abenaki served with American forces as scouts and guides, establishing a fort in the Abenaki community of Koasek. Western Abenaki, in New England and lower Canada, served in Ranger units.

While some Abenaki remained completely neutral and stayed out of it entirely, the majority sided with the British. This division of loyalty remained in effect through the War of 1812—and has been a sore spot for them ever since.

The New York Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

The New York Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

What Happened To Them After The Wars?

During these wars, the Western Abenaki lost countless warriors, and even a large number of their wives and children during ruthless raids that destroyed their villages. By the end, many Western Abenaki fled to northern New England and Quebec, while the Eastern Abenaki—who were not as severely affected by warfare—stayed where they were, in Maine.

What Happened To Their Settlements?

The American Revolution resulted in a win for the Americans, which equated to a massive loss of territory for the Abenaki, causing them to flee to refugee communities further north.

The wars may have brought them tremendous loss—but it also opened doors to other forms of change.

John Trumbull, Wikimedia Commons

John Trumbull, Wikimedia Commons

What Did The Abenaki Gain From The War?

When the Europeans came to North America, they didn’t come empty handed. And since those native to the land couldn’t stop them, they had no choice but to eventually give in to their foreign lifestyles.

As a result, the Abenaki became further involved in the fur trade, where they now exchanged beaver pelts for imported goods, such as tools and glass beads.

And while this may have been helpful, it eventually went too far.

William Faden, Wikimedia Commons

William Faden, Wikimedia Commons

What Did They Gain Through Trade?

As trade with Europeans became a more permanent practice for the Abenaki, it quickly escalated from tools and beads to more modern supplies and clothing. Eventually, Indigenous communities across the area became largely modernized—bows and arrows were replaced with pistols, animal hide coverups were replaced with jeans and t-shirts, and so on.

Not only did the Abenaki lose their lands—they were losing their culture too.

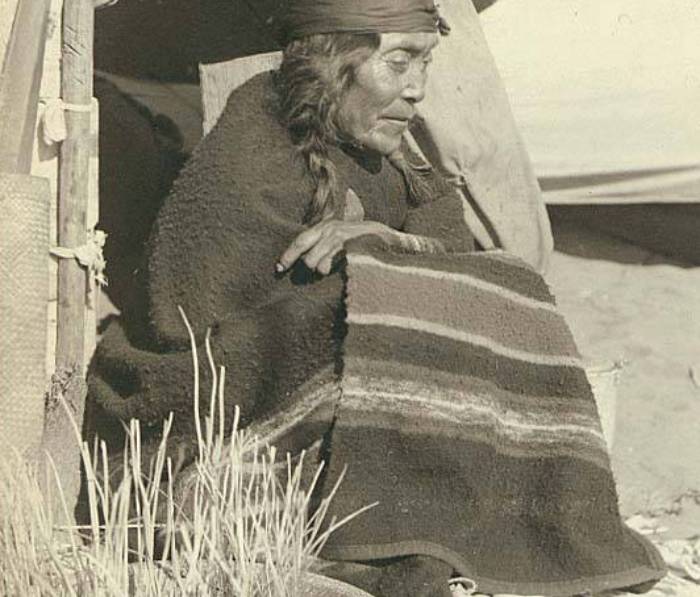

What Is Life Like For Abenaki Today?

Today, most Abenaki have gone all the way from hunting and gathering to taking up mainstream occupations. While some live on reserves and remain an integral part of their traditional communities, others have taken up modern life in other big American cities.

But even though their culture is endangered—it’s not completely gone yet.

Nebi: Abenaki Ways of Knowing Water, Made Here - from Vermont Public

Nebi: Abenaki Ways of Knowing Water, Made Here - from Vermont Public

Final Thoughts

More than ever, Abenaki today are working tirelessly to preserve their culture. With language courses and basket weaving traditions passed on, tribal elders are committed to rejuvenating their traditional practices before it’s too late.

You May Also Like:

The Most Devastating Event in Native American History

The Native American Tribe That Brought Victory To America

The Only Native American Tribe That Never Surrendered

Abenaki Chiefs and state leaders celebrate Abenaki Recognition and Culture Week, Local 22 & Local 44

Abenaki Chiefs and state leaders celebrate Abenaki Recognition and Culture Week, Local 22 & Local 44