A Divine Deluge

This is one of humanity's earliest written stories of power, mortality, and divine judgment. Through its narrative, we tend to explore questions about life, death, and the complex relationship between gods and human beings.

Ancient Legacy

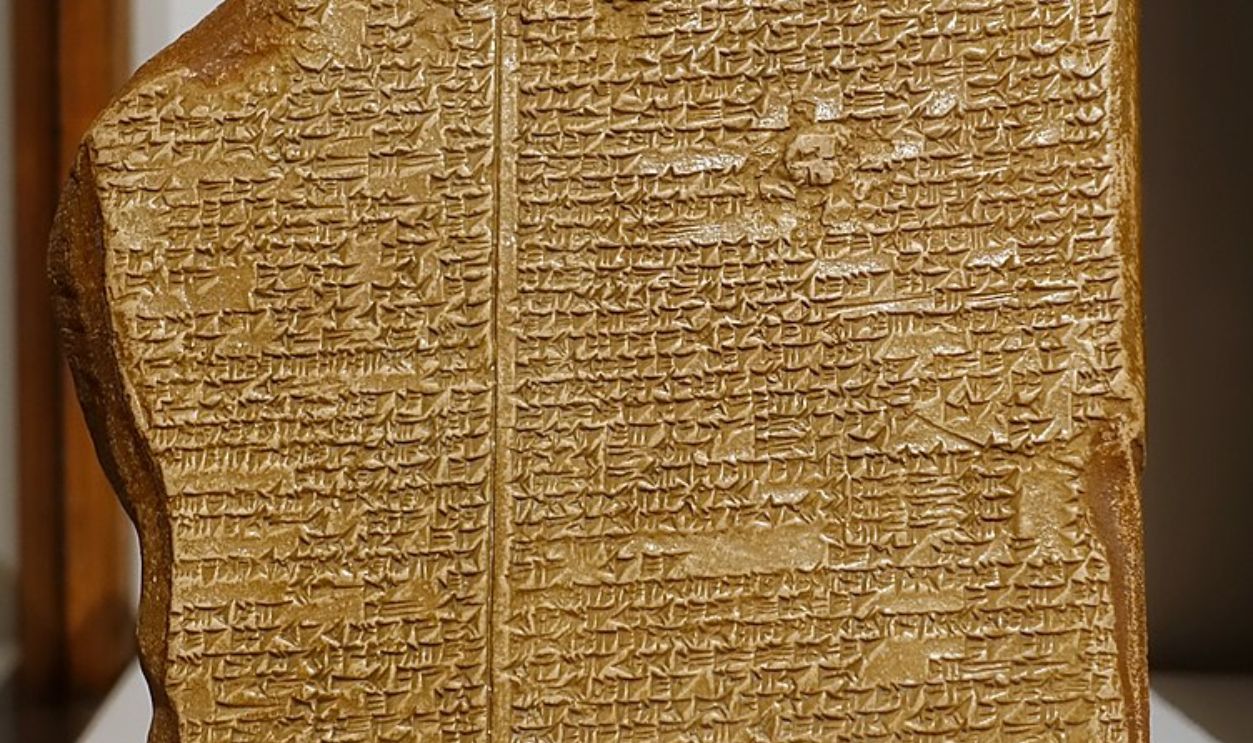

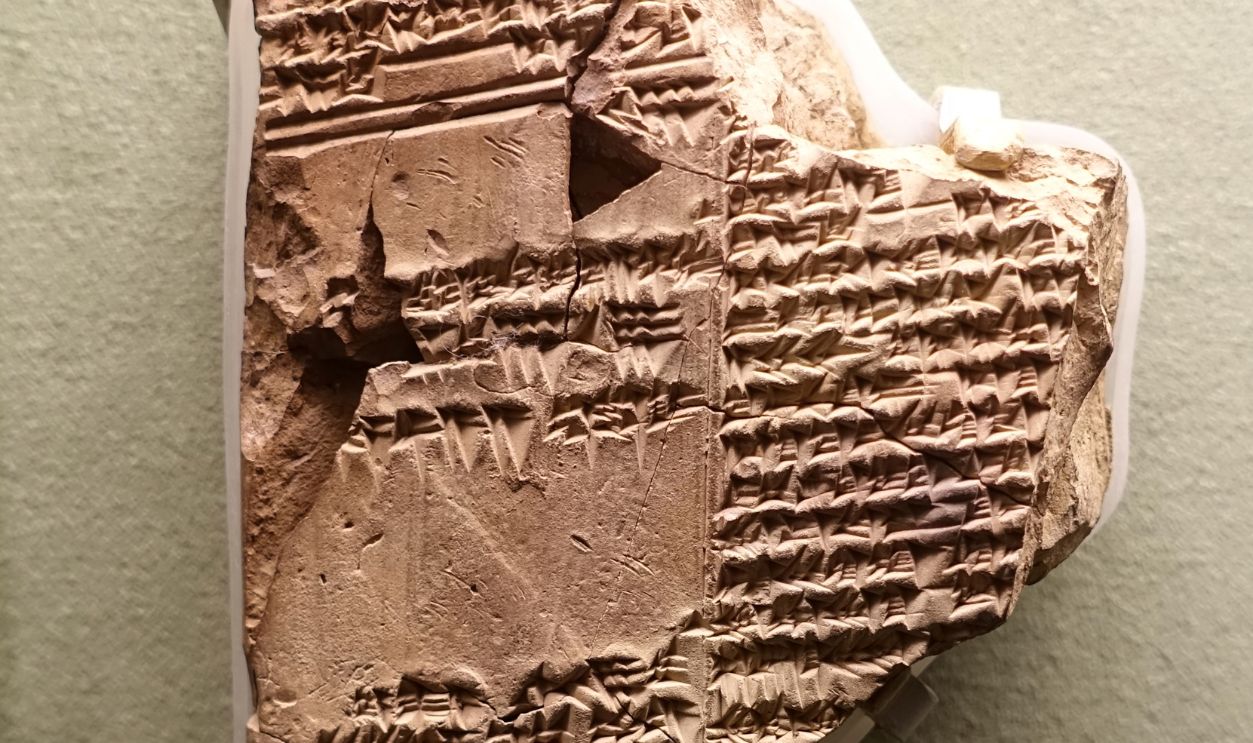

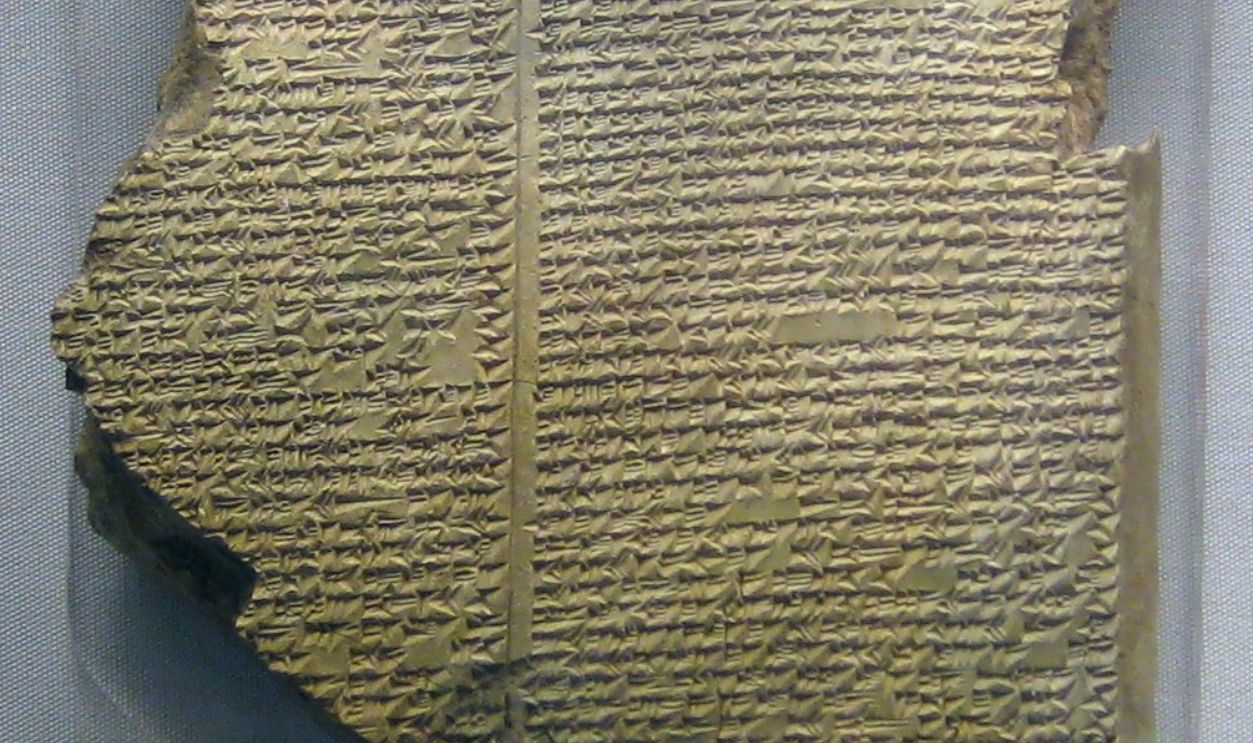

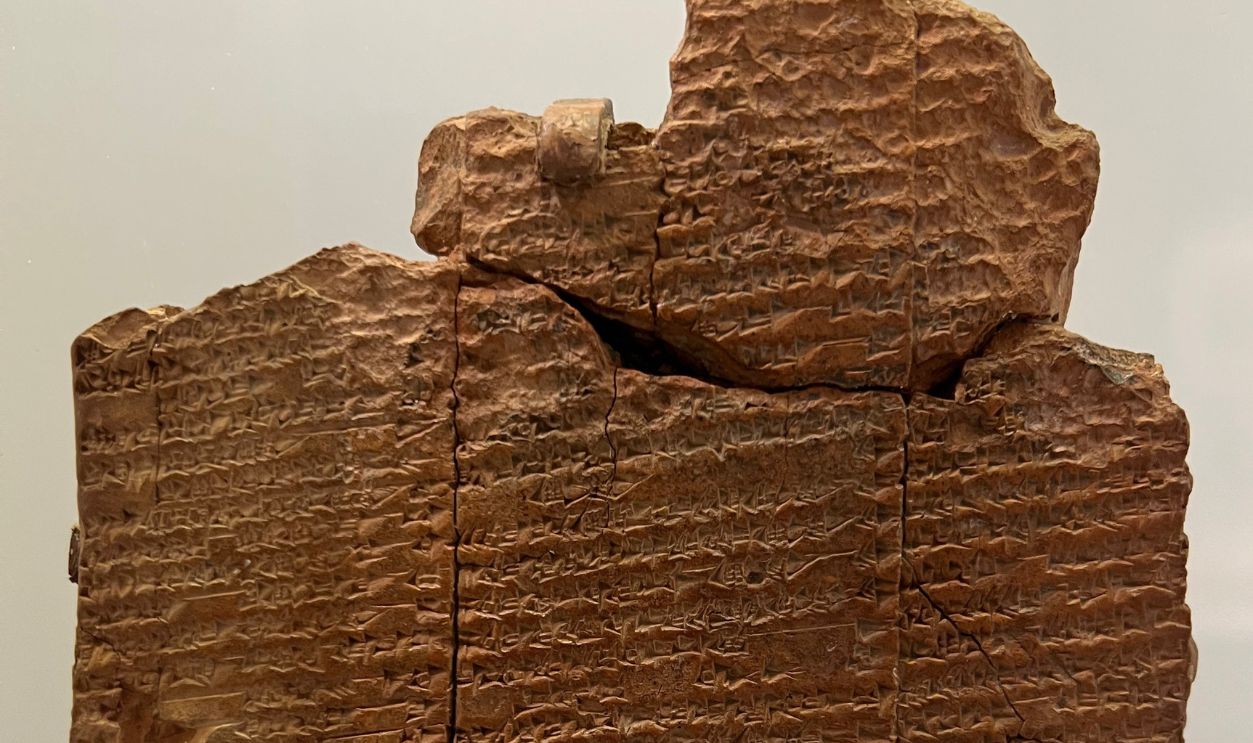

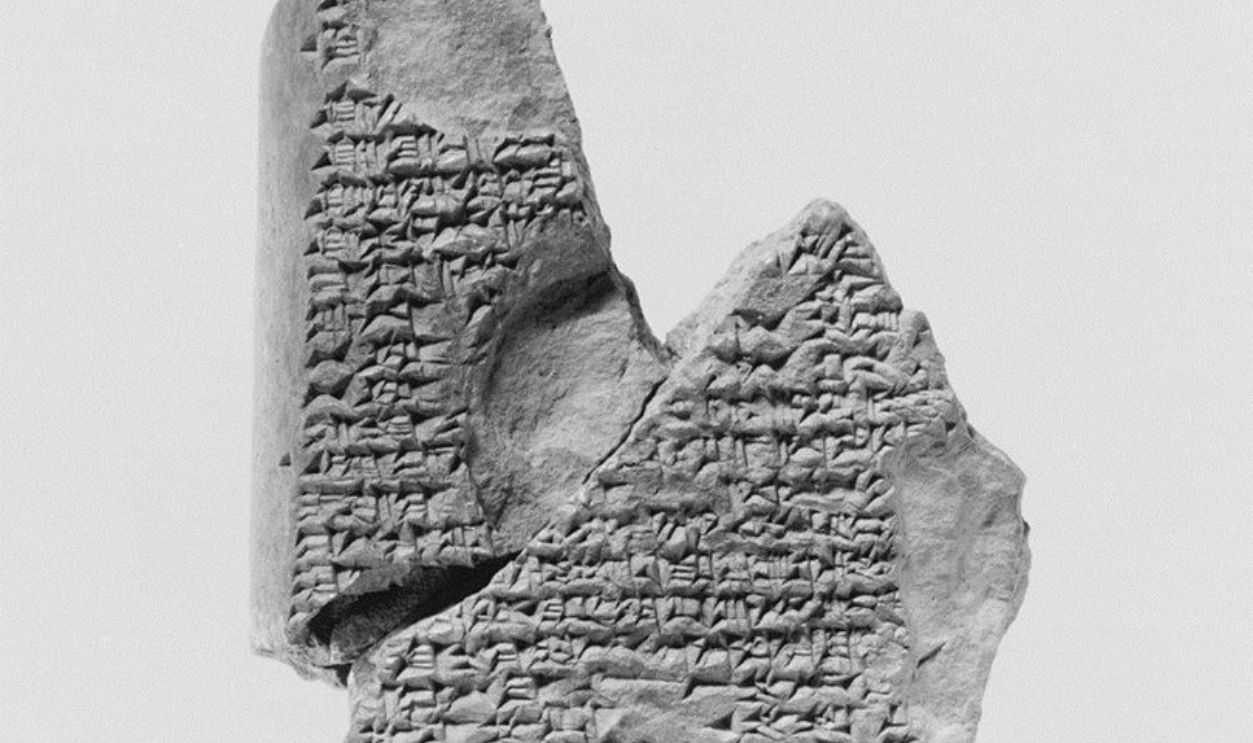

One of the oldest stories we know is about the flood from the Epic of Gilgamesh, which is found on clay tablets from ancient Mesopotamia. This tale has been preserved in cuneiform script for over 4,000 years, allowing us to glimpse into people's beliefs back then.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

About Gilgamesh

Gilgamesh is a legendary figure from ancient Mesopotamia, best known as the protagonist of the Epic of Gilgamesh. In mythology, this man is depicted as a semi-divine individual who is two-thirds god and one-third human.

Gwil5083, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Gwil5083, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Historical Context

King Gilgamesh is believed to have reigned around 2700 BCE in ancient Sumer, specifically in the city-state of Uruk. His historical existence is supported by archaeological findings like inscriptions and artifacts linked to rulers mentioned in the narrative.

Samantha, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Samantha, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Royal Heritage

These include the Aga of Kish and the Enmebaragesi of Kish. His lineage is described as being from Lugalbanda (priest-king) and Ninsun (goddess). Gilgamesh is also credited with substantial contributions to Uruk, mainly the construction of its massive walls.

Historical Dating

Archaeological evidence shows that the earliest Sumerian poems about Gilgamesh date back to the Third Dynasty of Ur, approximately 2100–2000 BCE. This dating is important for tracking the development of the Gilgamesh story through ancient times.

Sémhur (talk)derivative work: Zunkir, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sémhur (talk)derivative work: Zunkir, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sumerian Origins

The literary history of Gilgamesh starts with five Sumerian poems, including tales of his exploits, such as "Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld" and "Gilgamesh and Aga”. Over time, these Sumerian poems were woven into a connected narrative in Akkadian.

British Museum, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

British Museum, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Integration Of The Story

Sin-liqe-unninni is credited with compiling a standardized version of the epic that included Utnapishtim's flood story in Tablet XI between 1300 and 1000 BCE. His version is notable for its incipit, "ša nagba īmuru," translating to "He who saw the deep”.

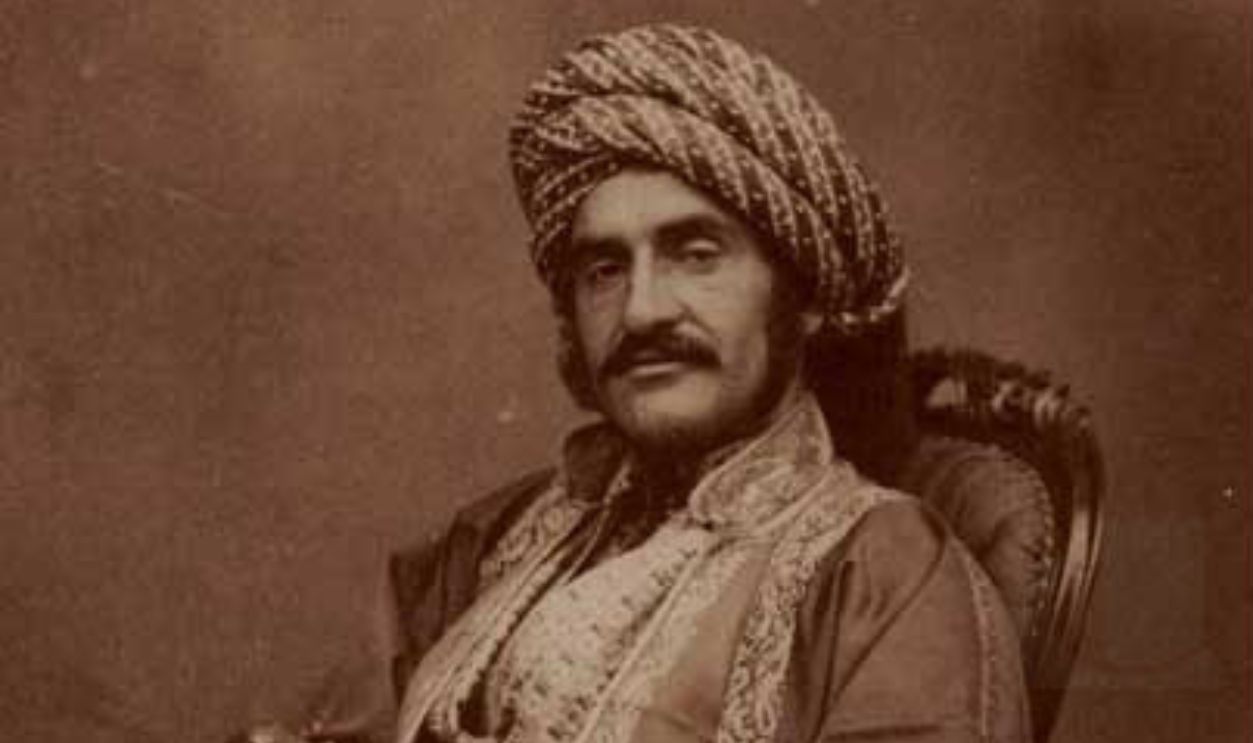

Initial Findings

Hormuzd Rassam first discovered the Gilgamesh flood tablet in Nineveh, an ancient Assyrian city in modern-day Iraq. During his excavations here between 1877 and 1882, he found these clay tablets. He is often recognized as one of the first Middle Eastern archaeologists.

Philip Henry Delamotte, Wikimedia Commons

Philip Henry Delamotte, Wikimedia Commons

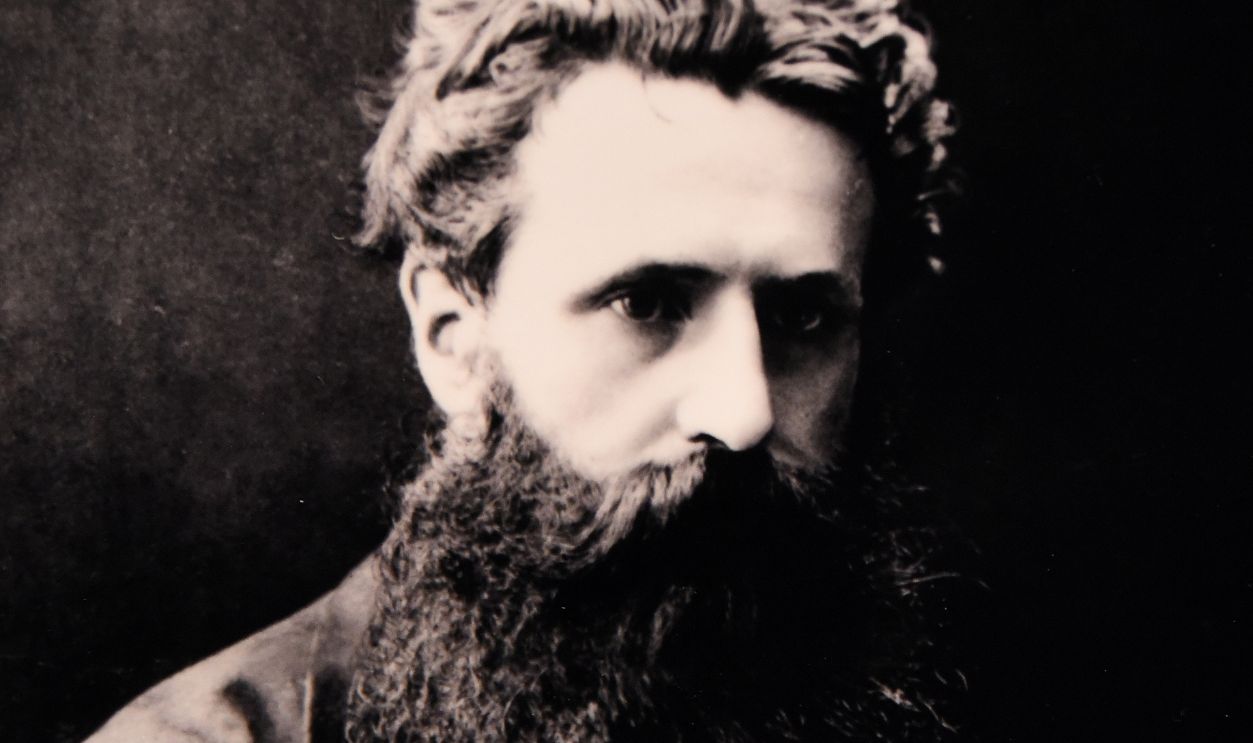

Smith’s Translational Discovery

Supporting him in 1872, British Museum assistant George Smith made a groundbreaking discovery. He basically translated the fragment of the flood tablet, known as Tablet XI of the Epic of Gilgamesh, from a seventh-century BCE Akkadian text.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Biblical Echoes

It was a significant moment in the study of ancient Mesopotamian literature, as it revealed a flood narrative similar to the biblical account of Noah's Ark. Smith famously exclaimed, "I am the first man to read that after more than two thousand years of oblivion”.

Simon de Myle, Wikimedia Commons

Simon de Myle, Wikimedia Commons

Additional Discoveries

In 1898, the Atra-Hasis tablet from around 1646-1626 BC was discovered. It is now located in the Morgan Library & Museum. Then, in 2007, Andrew George translated an ancient tablet from Ugarit about 3,200 years old, which told the story of Utnapishtim and the flood.

Expedition Findings

This expedition provided detailed descriptions of the provisions stored on the ark in the Epic of Gilgamesh. The text mentioned specific instructions about storing grain, furniture, goods, wealth, servants, and different animals within the vessel's confines.

Physical Description

The eleventh tablet, artifact K.3375, now resides in Room 55 of the British Museum. This precious clay piece measures 15.24 centimeters long, 13.33 centimeters wide, and 3.17 centimeters deep while preserving ancient cuneiform writing.

Iraq marks return of looted Gilgamesh Tablet from the US by Al Jazeera English

Iraq marks return of looted Gilgamesh Tablet from the US by Al Jazeera English

Divine Council

The story of the flood begins with the great gods Anu, Enlil, Ninurta, Ennugi, and Ea secretly planning to destroy humanity through a catastrophic flood due to the growing noise and wickedness. It is seen as a pivotal moment that tests humanity's resilience.

Version 1 Version 2, Wikimedia Commons

Version 1 Version 2, Wikimedia Commons

A Sacred Warning

However, God Ea breaks divine secrecy by warning Utnapishtim through a reed wall in a dream. He instructs him to demolish his house and build a large vessel to survive the flood. This act of betrayal against the other gods shows Ea's compassion and cleverness.

c. 2300 BC (design); 2012 (this file), Wikimedia Commons

c. 2300 BC (design); 2012 (this file), Wikimedia Commons

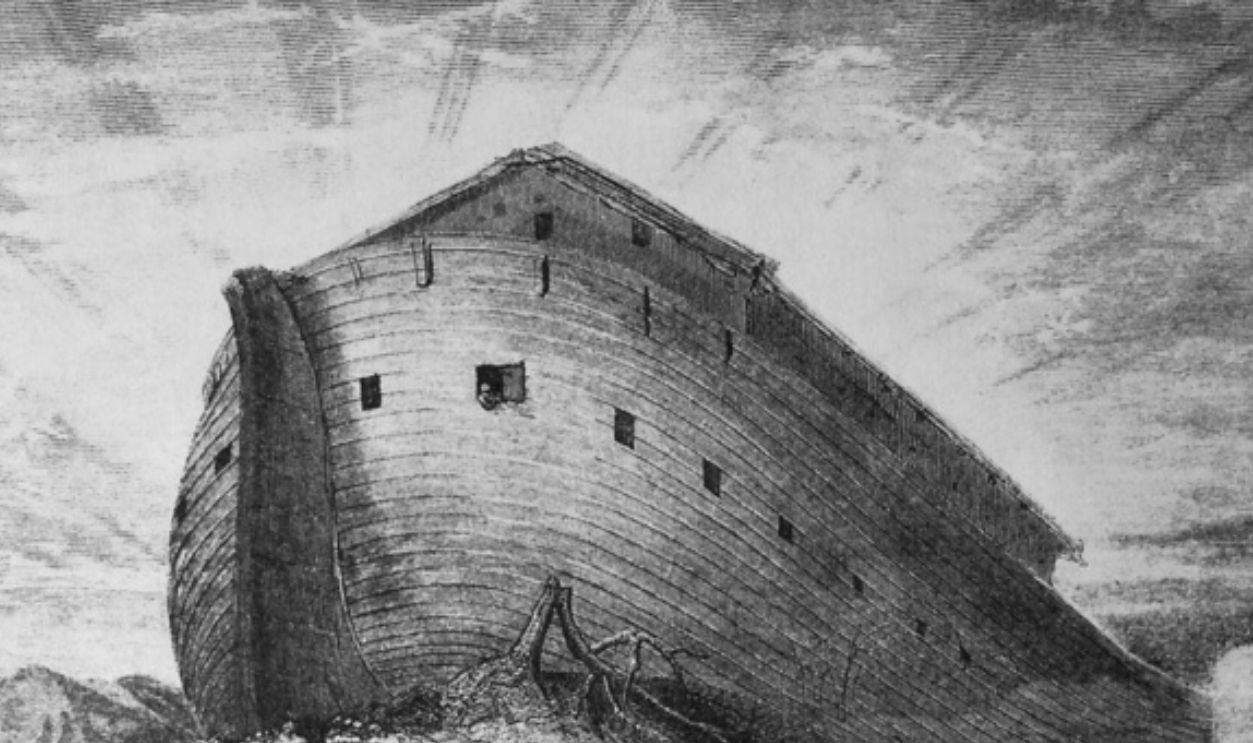

Boat Specifications

God Ea also provides Utnapishtim with dimensions for constructing the ark. He wanted it to be 180 feet high and have six decks. God Ea also emphasized that Utnapishtim gathered his family and the seeds of all living creatures to ensure their survival.

Addressing Questions

Anticipating that people will surely question Utnapishtim’s actions as he builds the boat, Ea comes up with a lie. He advises Utnapsihtim to tell them that he must leave Shuruppak because Enlil is angry with him and is, therefore, seeking a new home.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Construction Begins

The construction involved skilled carpenters and reed workers who were gathered to build this massive vessel. The exterior walls stretched 120 cubits, with six decks divided into seven and nine compartments. Also included were strategic water plugs.

Kaleeb18, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Kaleeb18, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Resource Requirements

The boat's construction demanded immense resources. The narrative specifies that 10,800 units of raw bitumen and 10,800 units of oil were necessary for building the vessel. Oil also had ceremonial significance in ancient Mesopotamian culture.

Javier Cruz Acosta, Shutterstock

Javier Cruz Acosta, Shutterstock

Loading Process

Soon, as the storm clouds started taking over, Utnapishtim loaded precious metals, family members, craftsmen, and animals aboard. The boat master, Puzurammurri, sealed the entry and started preparing for nature's fury to reveal its power.

Javier Cruz Acosta, Shutterstock

Javier Cruz Acosta, Shutterstock

The Storm's Arrival

It was the thunder god Adad who announced that the storm was coming with his loud rumbling. The storm gods Shullat and Hanish wreaked havoc on the mountains and fields while Erragal yanked out mooring poles, leading to destructive overflowing dikes.

British Museum, CC BY-SA 2.0 FR, Wikimedia Commons

British Museum, CC BY-SA 2.0 FR, Wikimedia Commons

Fear Of The Divine

This terrible flood not only devastated the earth but also instilled fear in the gods themselves. They retreated to the heavens of Anu, cowering in fear like dogs against the outer walls. Black clouds created unprecedented darkness across the land.

The Goddess's Lament

Ishtar, known as the Mistress of Gods, expresses her distress with cries that resemble the pain of childbirth. She questions why she commanded such destruction, lamenting that those lost were her own people whom she had brought into existence.

Sailko, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sailko, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Duration Of The Storm

The relentless wind and flood caused havoc on the Earth for six days and six nights, symbolizing an overwhelming and unyielding force of nature. On the seventh day, the storm's intensity changed, pounding intermittently like labor pains.

Aftermath Revealed

Very similar to Noah’s tale, when Utnapishtim opened a window of the ark after the flood, he experienced a moment of relief. Fresh air touched his face amidst the devastation surrounding him. It was a transition from chaos to hope.

Thomas Pennant, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Pennant, Wikimedia Commons

Mountain Landing

The vessel then came to rest on Mount Nimush and remained stable for several days. This momentous landing was seen as the beginning of humanity's chance for a fresh start and the opportunity to rebuild society in a manner that would avoid such transgressions.

Bird Messengers

After the floodwaters began to recede, Utnapishtim tested for dry land by releasing three birds from the ark. First, a dove to search for land. The dove returned to the ark, indicating that there was no suitable place for it to rest, signifying the continued presence of floodwaters.

Prasan Shrestha, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Prasan Shrestha, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Raven Returns

Second was the swallow. Like the dove, the swallow also came back without finding dry land, reinforcing the sense of despair and uncertainty about the state of the world. Finally, the third bird, the raven, did not return, showing that it had found dry land.

Sacrifice Ritual

After the ark came to rest, Utnapishtim performed a ritual by offering sacrifices atop a mountain ziggurat. He arranged fourteen vessels filled with reeds, cedar, and myrtle. The fragrant smoke from the incense served to attract the gods, who were drawn to them.

tobeytravels, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

tobeytravels, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Spiritual Gathering

Hence, the goddess Ishtar arrived adorned with her lapis lazuli necklace, a precious stone. She stood there, vowing to never forget the destruction, while other deities also gathered around the sacrificial offering, drawn by its appealing aroma.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Enlil's Rage

But here comes the twist. When Enlil arrived and saw Utnapishtim and his wife, he became furious, demanding to know how any living being could be alive. His initial intent was total destruction, and the existence of survivors directly contradicted his plan.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Debate

Anyway, Ea stood up for his actions against Enlil's plan to wipe out humanity. He thought it was harsh to destroy everyone, as not all humans were to blame. Instead, he suggested using something like plagues or famine as a punishment.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

An Eternal Reward

As a resolution, Enlil grants Utnapishtim and his wife immortality as a prize for their survival and obedience. He allowed them to live eternally by transporting them to the mouth of the rivers. It was a divine reward that turned ordinary humans into godlike beings.

Danbury, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Danbury, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Gilgamesh’s Quest For Eternity

Following the flood, Gilgamesh seeks out Utnapishtim, who has been granted eternal life, and hopes that Utnapishtim can teach him how to avoid death. So, to test Gilgamesh's claim that he wants to live forever, Utnapishtim challenges him to stay awake for a week.

ZulaikhaN, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

ZulaikhaN, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Acceptance Of Mortality

Gilgamesh tries but ultimately fails. While on his way back to Uruk, he takes along a miraculous plant that restores youth, but sadly, a serpent steals it. He then realizes that while he cannot escape death, he can achieve immortality through his deeds and legacy as a ruler.

Louvre Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Louvre Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Textual Evolution

The story of the flood exists in three Mesopotamian versions: the Epic of Gilgamesh, Eridu Genesis, and the Atra-Hasis epic. Each of these narratives gives unique details and perspectives, showing how the flood myth evolved over time.

Early Sumerian Account

For instance, the "Eridu Genesis" is an earlier Sumerian account that describes how the gods created humanity to serve them but decided to destroy them with a flood. In this version, Ziusudra is warned by Enki and builds a boat to survive.

Onceinawhile, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Onceinawhile, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sacred Geography

Eridu, one of the oldest cities in Mesopotamia, is important, particularly due to its association with the ziggurat dedicated to the god Ea and its geographical context near the apsû. This place is believed to be a vital source of freshwater.

Hardnfast, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Hardnfast, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Symbolism Of Apsû

Now, the apsû, which is a term referring to the underground freshwater ocean or abyss, represents physical water as well as fertility and life. This makes it an essential element in the creation myths associated with Enki, who is often linked to water and wisdom.

Editorial Changes

Some later editors modified passages to align with changing theological perspectives and cultural values. Some early versions depicted gods with very human-like traits, but then editors removed references to such things as experiencing hunger and thirst.

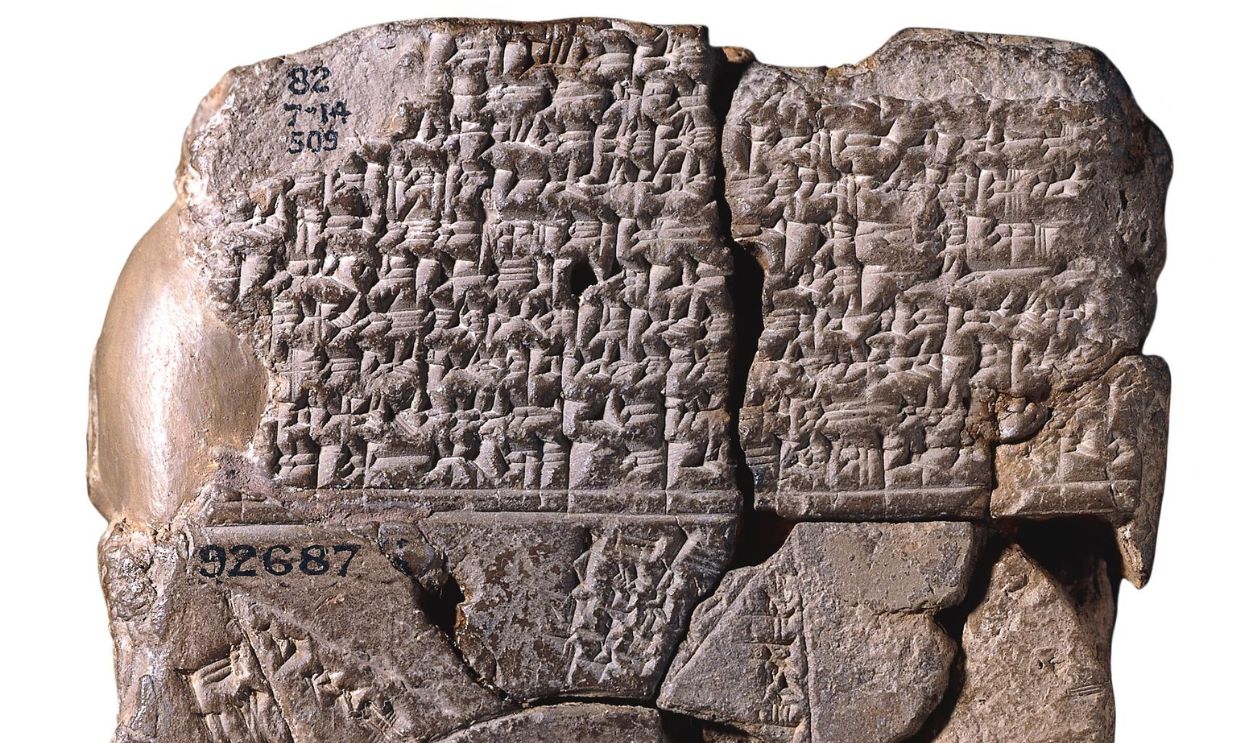

A Comparison With The Atrahasis Epic

The Atrahasis epic is primarily told in a third-person narrative, while the Gilgamesh Epic uses a first-person perspective as Utnapishtim recounts his story to Gilgamesh. Again, Atrahasis reflects a polytheistic worldview, while Gilgamesh focuses more on individual experiences of mortality and immortality.

British Museum. Object Number: 92687., Wikimedia Commons

British Museum. Object Number: 92687., Wikimedia Commons

A Comparison With The Atrahasis Epic (Cont.)

The Atrahasis offers additional details and emotional depth that are often omitted in the Gilgamesh version. In the Atrahasis epic, Atrahasis hosts a banquet for his people, inviting them to celebrate. However, he is deeply troubled by the knowledge of the impending flood.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Universal Flood Theory

Scholars such as A.R. George, Lambert, and Millard interpret the flood in the Atrahasis epic as a worldwide event rather than a localized catastrophe. For instance, the phrase "dragonflies filling the river" is seen just as a metaphor for the destruction caused by the flood.

An Enduring Message

So, the epic concludes with a powerful affirmation of human achievement, particularly through the celebration of the walls of Uruk. It shifts the story from being about destruction and loss to highlighting how strong civilization can be, even when dealing with mortality.

BrokenSphere, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

BrokenSphere, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons