The Horrors He Faced Never Defeated Him

Born in 1835, Ernest Giles was one of history's most cursed explorers—but his fourth expedition brought him face to face with a real-life nightmare.

He Wasn't Born In Australia

Though he would eventually be known as "the last of the Australian explorers," Ernest Giles wasn't actually born in Australia. On July 20, 1835, his parents William and Jane welcomed him into their lives—and young Giles spent most of his youth growing up in Bristol, England. Little did he know, his destiny lay in a far-off country.

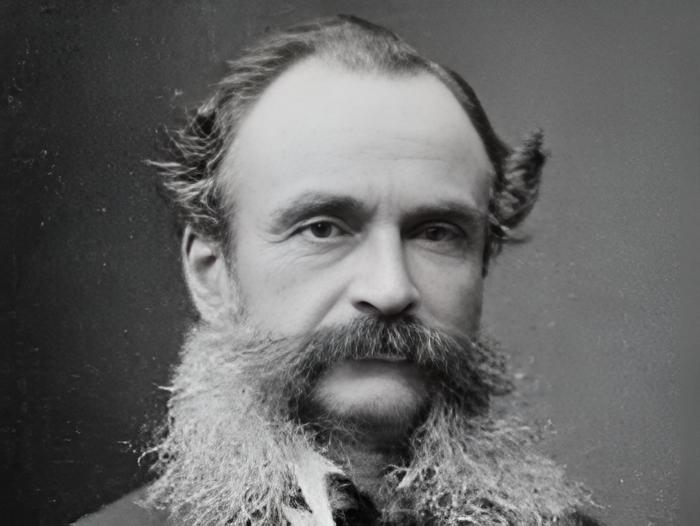

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

His Family Struggled To Get By

Giles's family moved to Adelaide, Australia—for quite a disheartening reason. Though they'd managed to get by quite swimmingly in London, their fortunes took a worrying downturn. Therefore, a fresh start in a new country seemed like the perfect way to turn things around.

Luckily, their risky decision paid off.

D. Darian Smith, Wikimedia Commons

D. Darian Smith, Wikimedia Commons

He Moved To A New Country

At the age of 15, Giles joined his parents in Australia. Both of his parents had tasted sweet success with their careers: His father William found a job with HM Customs, and his mother Jane began her very own school for girls. But for Giles, finding his true calling came with a few twists and turns.

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

He Had A Revelation

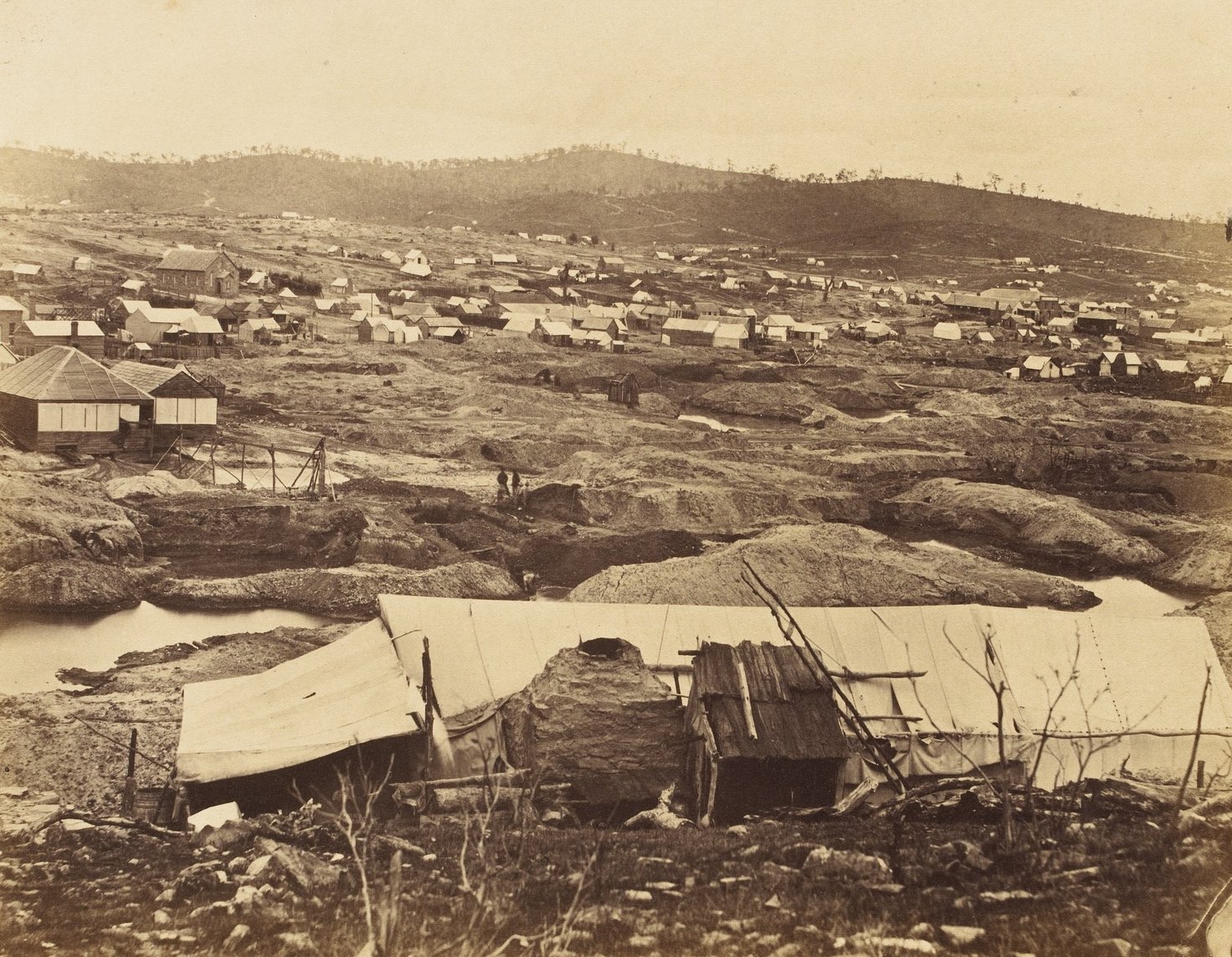

In 1852, Giles tried his hand at multiple fields of work. Not only did he take a chance on the Victorian goldfields but he also got a taste of clerical work. However, a revelation began to dawn on him—one that only comes with growing up and realizing what path in life suits one best.

Richard Daintree, Wikimedia Commons

Richard Daintree, Wikimedia Commons

He Wasn't Meant To Be A City Boy

As it turned out, city life just wasn't the right fit for him—and so Giles went back to the drawing board. It was in Australia's backcountry that Giles began to get his hands dirty—acquiring essential skills for the life of exploration that lay ahead of him. Then, in 1865, he kicked things up a notch.

Richard Daintree, Wikimedia Commons

Richard Daintree, Wikimedia Commons

He Got The Exploration Bug

Giles really caught the exploration bug when he had to journey through the Yancannia Range. His goal? To discover pastoral land and terrain suitable for growing hemp. But this fateful task was only the beginning.

Tim J Keegan, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Tim J Keegan, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Undertook His First Expedition

It wasn't until August 1872 that Ernest Giles finally set out on his first official expedition. It was a small party—just him and two other men. They were charged with exploring exciting, uncharted territory in central Australia. But if there was one thing Giles wasn't blessed with—it was beginner's luck.

Ndaaunhi, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ndaaunhi, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

His Best-Laid Plans Hit A Snag

Giles's team began in Australia's northern territory, Charlotte Waters, and headed for the Missionaries' Plain—but they soon ran into trouble. Though they navigated through the Finke valley, there came a point when they could travel no further.

Cgoodwin, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Cgoodwin, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

His Horses Were Too Tired

Though Giles desperately hoped to discover a path to Western Australia, nature stood in his way—namely Lake Amadeus, which stopped the expedition in its tracks. Of course, that wasn't the only problem. To add insult to injury, the team's horses were utterly exhausted.

He Didn't Want To Give Up

Though it pained him to do so, Giles had no choice but to admit defeat and accept his second-in-command's sage advice: It was time to turn around and head home to Adelaide. After months of eager travel, Giles completed his journey in January 1873. Of course, his story didn't end there.

South Australian government photographer, Wikimedia Commons

South Australian government photographer, Wikimedia Commons

He Wanted So Much More

Giles's first expedition was more of a success than he realized, especially since his team was so small. He, however, was extremely hard on himself—and felt like a complete failure. Still, this crushing disappointment wasn't enough for him to throw in the towel forever. If anything, it only lit a burning fire of ambition within his heart.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

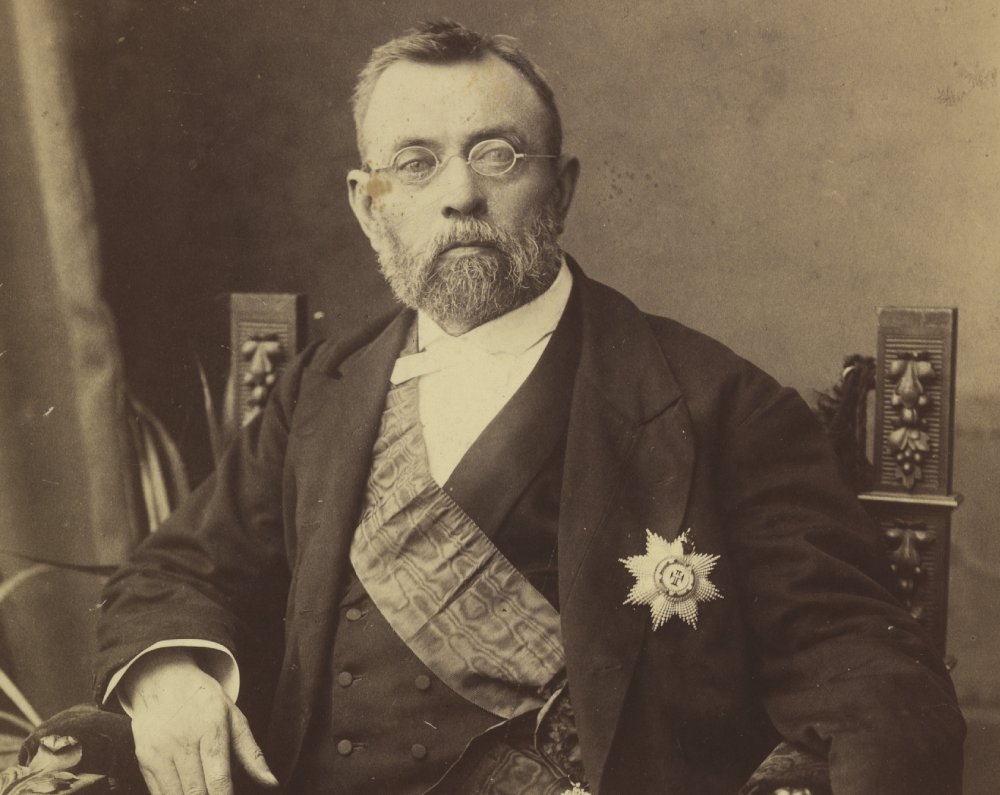

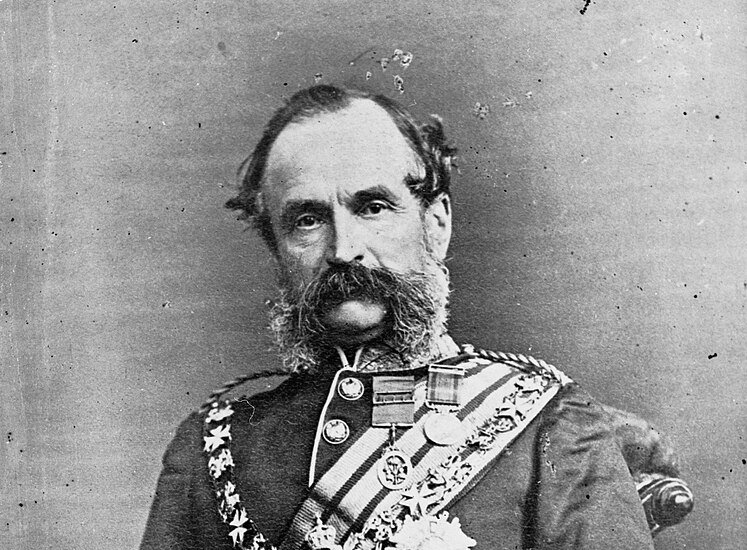

He Had A Special Benefactor

That same year, Giles turned to the same man who helped organize his first expedition—his friend Baron von Mueller. Mueller was a very talented man—a geographer, botanist, and physician, as well as Ernest Giles's benefactor. Again, Mueller came through for Giles, making it possible for him to once again trek into the unknown.

National Library of Norway, Wikimedia Commons

National Library of Norway, Wikimedia Commons

He Set Out On A Second Expedition

On August 4, 1873, Giles set out with three men, including first assistant William Tietkens and fellow explorer Alfred Gibson. They had a lofty goal in mind, hoping to traverse Western Australia's deserts—moving from east to west. None of these eager adventurers knew just how tragic this would prove to be.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

He Faced Unknown Territory

This expedition was significantly different than Giles's first failed venture. To begin with, he had a different starting point, south of the previous one—and began moving west from the Alberga River. Within a month, they made some exciting discoveries.

He Named A River

While in the Musgrave Ranges, Giles and his team came across a river—and left their mark on its running waters by calling it the Ferdinand. But though they seemed to be making decent progress, they soon realized they had a mounting problem on their hands.

He Couldn't Find Water

Unsurprisingly, the environment was excruciatingly arid—the air and ground gasping for moisture. Giles tried to explore the area, moving out in different directions, but no matter where they turned, they struggled to find reliable water sources. Considering they needed to keep their horses hydrated and energetic, this stunning lack of water became their greatest concern.

But this early worry was merely an omen for the nightmare to come.

He Didn't Travel In A Straight Line

Giles and his men continued across the desert, backtracking where necessary. By the end of December, they'd already moved through Mount Scott. For months, they trekked on—and in April 1874, they finally made it to the far west. It should have been an exciting time, but instead, fate descended on the party and dealt them a brutal hand.

James St. John, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

One Of Their Horses Perished

You see, around this time, both Ernest Giles and Alfred Gibson had ridden ahead on their horses, scouting out the path ahead. That's when disaster struck. Gibson's horse sadly perished, meaning they were one animal short. A difficult decision had to be made.

He Made A Perilous Journey On Foot

Giles took charge of the situation, directing Gibson to take his own horse and return to their camp for help. He likely thought he'd given himself the shorter end of the stick. After all, he'd have to start the return trip on foot, which was no easy feat. Putting one foot in front of the other, Giles had no clue that he would never see Gibson again.

Ghreumaich, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ghreumaich, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Almost Died In The Desert

It took eight days of solo travel for Giles to finally reunite with the rest of his party—but he was certainly worse for wear. Over a week spent in such harsh conditions brought him right to death's doorstep. Though utterly exhausted, he'd managed to survive.

However, any relief he experienced in reaching his camp was punctuated by the bad news he received upon arrival.

His Friend Went Missing

This nightmarish chapter of Giles's life quickly went from bad to worse. As it turned out, Gibson had not made it back to the depot. So where in the world was he?

Ghreumaich, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ghreumaich, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Couldn't Find Him Anywhere

Though Giles and his team desperately searched for their missing comrade, it seemed that Gibson was nowhere to be found. It was an utterly tragic loss. Compounded with the disheartening reality that their provisions had dwindled to almost nothing, the feelings of both failure and grief permeated the air.

spelio, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

spelio, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Admitted Defeat

Giles had no choice but to call an end to this second expedition. The surviving party turned around on May 21, heading for Charlotte Waters, which they reached by mid-July. Once again, the mission reeked of utter defeat. They had not crossed the continent and they had lost one of their own.

Still, Giles had soldiered on until he could no longer—his resilience a winning aspect of his character. Of course, the expedition did have some silver linings.

Mark Marathon, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mark Marathon, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Named The Desert After Him

In memory of Alfred Gibson, Giles fittingly named the desert that had claimed his friend Gibson Desert. But that wasn't the only piece of land he got to name.

Robert Whyte, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Whyte, Wikimedia Commons

He Was The First

Though Giles ran into some sticky situations during his first two expeditions, he made it home with some unique experiences in his back pocket. For instance, he became the very first European to set eyes on Mount Olga. However, initially, he wanted to give the domed rock formations a completely different name.

He Wanted To Give It A Different Name

Because Baron von Mueller was such an important person in Giles's life, he initially wanted to honor his benefactor by naming this discovery after him—Mount Mueller. Surprisingly, it was Mueller himself who turned Giles in a different direction, urging him to name it after Queen Olga of Württemberg instead.

He Wrote It All Down

After two failed expeditions, Ernest Giles was only getting started. By 1875, he'd already collected enough material to publish the stories of his travels. Throughout his trying adventures, he'd run through several diaries—and he eventually put them out into the world, titling them Geographic Travels in Central Australia.

The same year, he was ready to set out once again.

He Didn't Give Up

Giles's adaptability was one of his finest traits—and he certainly wasn't a quitter. He accepted the support of Sir Thomas Elder in 1875, which allowed him to turn his hopes of a third expedition into a reality. In mid-March of that year, he left Fowlers Bay, traveling north. Once again, he would have to face each curveball as they came.

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

He Traveled To Beltana

No stranger to switching up his intended route, Giles wound up having to backtrack thanks to extremely arid conditions. In order to reach Sir Thomas Elder at Beltana, he had to move eastward, traveling around the top of Lake Torrens. Once at Beltana, his next great adventure awaited him.

He Brought Camels

For his fourth expedition, Giles set out into the Australian country with some new furry friends at his side—camels—a whole caravan of them, in fact. In order to handle these animals properly, Giles welcomed an expert to his crew.

National Library of Australia, Wikimedia Commons

National Library of Australia, Wikimedia Commons

He Worked With An Experience Cameleer

The cameleer Mahomet Saleh had a studied hand and had been on expeditions in the past. Two years before joining Giles's team, he'd worked alongside another explorer—Peter Warburton. However, the camels weren't the only thing that differentiated this expedition from Giles's previous attempts.

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

He Always Ran Out Of Water

You see, the true Achilles' heel of Giles's other expeditions was their water supply. Their horses had always reached a point of such physical exhaustion that they ran into trouble. Constantly looking for water sources slowed them down. This time, however, they made a significant change.

He Brought Water With Him

Instead of collecting water as they went, Giles made the smart move of packing water for the journey. For a while, this proved to be highly convenient. However, this strategy wasn't fail-safe. After all, what happened when the water ran out?

CSIRO, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

CSIRO, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Watched History Repeat Itself

Unfortunately, this was a question that Giles and his team eventually had to ask themselves when, in September 1875, they found themselves without water. History had repeated itself all over again.

His Resolve Never Waivered

The expedition faced the brutal desert with no clue as to when they might stumble across a water source. As such, the men's spirits began to wane. Ernest Giles's resolve, however, never swayed for an instant. It was during this particular water shortage that he confessed something chilling to his men.

He Refused To Turn Around

Giles openly communicated with his team, telling them that he had no plans of abandoning the route. He understood that the expedition had become a matter of "life or death". However, he did make them one tantalizing offer.

He Gave Them An Out

Considering their nightmarish situation, Giles suggested that if multiple members wanted to turn around, he would give them some camels and food for the return journey. They would have to either retrace their steps or head for Eucla Station. The team's response was shocking.

He Won Them Over

According to Giles himself, his daring enthusiasm for the expedition made an indelible impression on his men. Giles was certain that the severe conditions they faced would only make their victory so much sweeter. In the end, they all agreed to soldier on—and were ready to sacrifice their lives in the attempt.

But this bravado would soon be worn down.

He Felt Responsible For Their Fates

Though Giles's men pledged their lives for him, their morale whittled down as they covered miles and miles without finding water. Giles later wrote that he began to feel the pressure for having led his team down a potentially fatal path. But though they had death on their minds, salvation was closer than it seemed.

He Went 17 Days Without Water

Nearing the end of the month, Giles's group had traveled for a whopping 17 days—323 miles—and still hadn't managed to locate a water source. Then, on September 25, one of the Aboriginal guides made the sweetest discovery possible.

He Found A Spring In The Sand Dunes

Tommy Oldham became the expedition's hero after he stumbled across a much-needed water supply in the middle of the sand dunes. It was an incredible stroke of luck, and Giles later called this water source the Queen Victoria Spring.

He Found His Footing

The team had been so sure that their end was at hand when they finally found the spring. Following this miraculous find, they hunkered down for over a week to regain their strength. Feeling refreshed and finally hydrated, they continued moving westward. But just 10 days after setting out again, they encountered a brand new danger.

They Faced Down Aggressive Aborigines

Turns out, their dwindling water supply wasn't their only enemy. The group wound up in trouble once again when several Aborigines became so aggressive with them that Giles had no choice but to use firepower to ward them off. Luckily, they overcame this nightmarish bump in the road—and from there on out, the expedition's journey to Perth seemed to be smooth sailing.

He Made It To Perth

Giles and his party finally made it to Perth in November 1875—and it was a day of celebration. It was finally time to pump the brakes on this successful mission. Giles remained in Perth for the next two months and then geared up for his fifth and final expedition—the journey home.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

He Made The Trip Twice

In January 1876, Giles worked his way home, following a slightly different route—400 miles to the north. It took him most of the year to cross half of the country. When he finally made it back to Adelaide, the finish line marked a heartening truth: Giles had journeyed across the continent's western half twice.

Unfortunately, not everyone saw the value of his achievements.

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

He Wasn't Appreciated

The Australian governments didn't hold Ernest Giles's work in high esteem—and seemed to shun him entirely. Not only were they unwilling to give him any rewards for his accomplishments, but they had no interest in funding any of his future projects. In fact, one governor even made a scathing comment about Giles's character.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

His Reputation Was Slandered

In 1881, Governor Sir William Jervois did Giles so dirty by stating, "I am informed that he gambles and that his habits are not always strictly sober". However, such poor reviews didn't stop Giles from sharing his fruitful experiences.

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

State Government Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

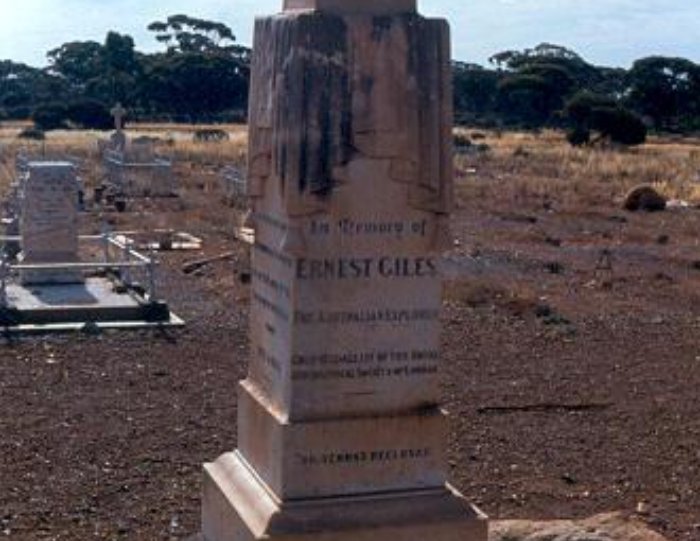

He Succumbed To Pneumonia

In the years following his major expeditions, Giles continued to publish works about his adventures. He also traveled on a smaller scale and eventually worked as a clerk in Coolgardie. It was in this Australian town that he lived out the rest of his days, eventually succumbing to pneumonia in 1897.

Walter Holden-Belmont, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Walter Holden-Belmont, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

More People Should Know His Name

Though Ernest Giles's name is not well-known today, his utter devotion to exploration in the face of failure—not to mention his passion for trekking into the unknown—makes his story well worth remembering.

Felix Dance, Wikimedia Commons

Felix Dance, Wikimedia Commons