Thames' Foul Play

When millions of people in London started dumping their waste into the Thames, the river decided to fight back with a highly intolerable stink in 1858. Who would have thought that a nauseating crisis like this would bring about a sanitation revolution in London?

Historical Context

In the 1600s, the first brick sewers were constructed in London, crossing ancient rivers like the Fleet and Walbrook. Around 200,000 cesspits and 360 sewers were present in the city by 1856, although many of them were badly maintained and even leaked methane.

Samuel Scott, Wikimedia Commons

Samuel Scott, Wikimedia Commons

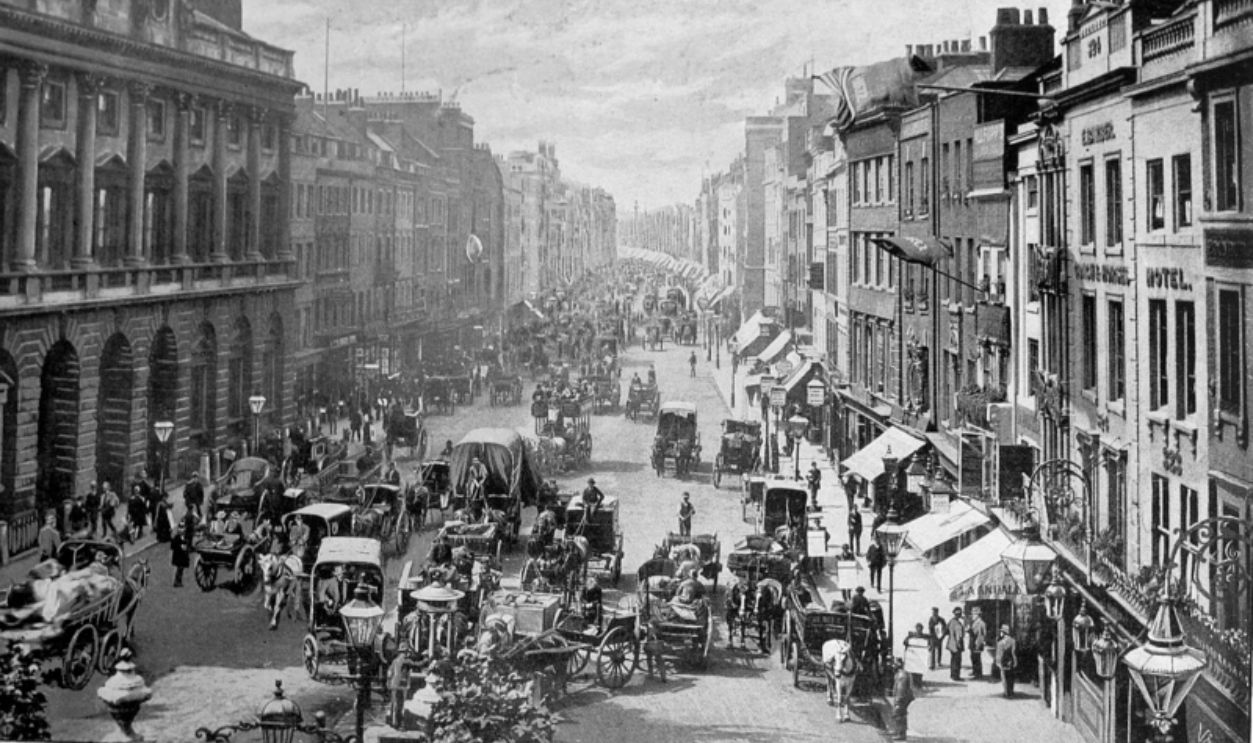

Population Pressure

The population of London skyrocketed from one million to three million between 1800 and 1850. The overwhelming volume of waste that was dumped into the Thames was facilitated by the replacement of chamber pots with flushing toilets and wooden pipes with iron ones.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

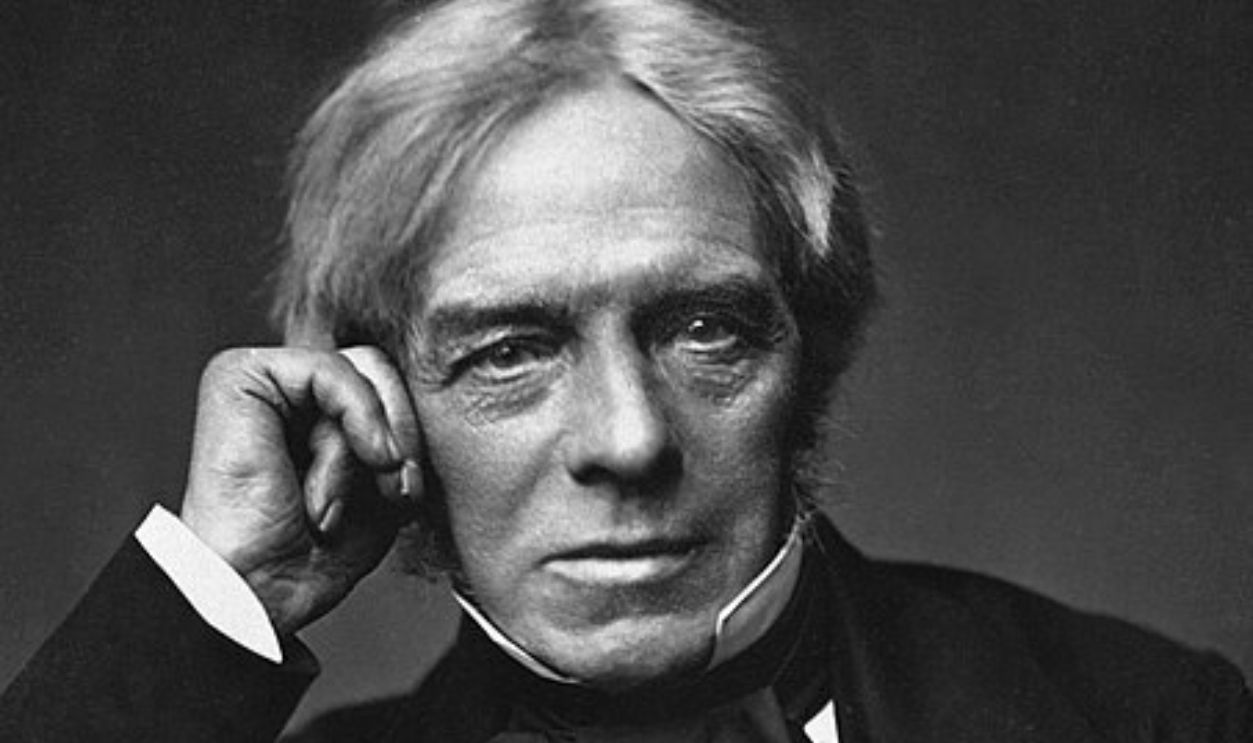

Thames Condition

Then, in July 1855, scientist Michael Faraday conducted a test on the River Thames' water. He dropped some white moistened paper into it and reported that the waste formed dense clouds visible at the surface. Faraday finally declared, "The whole river was a real sewer".

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

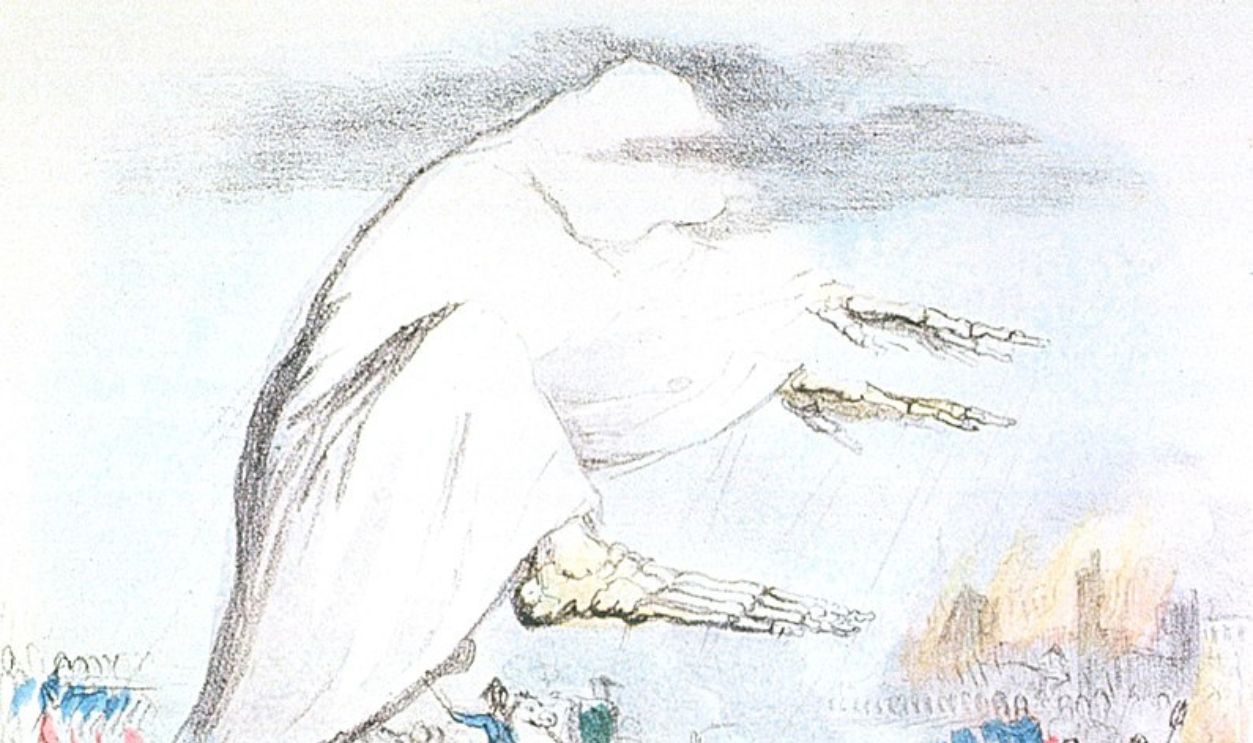

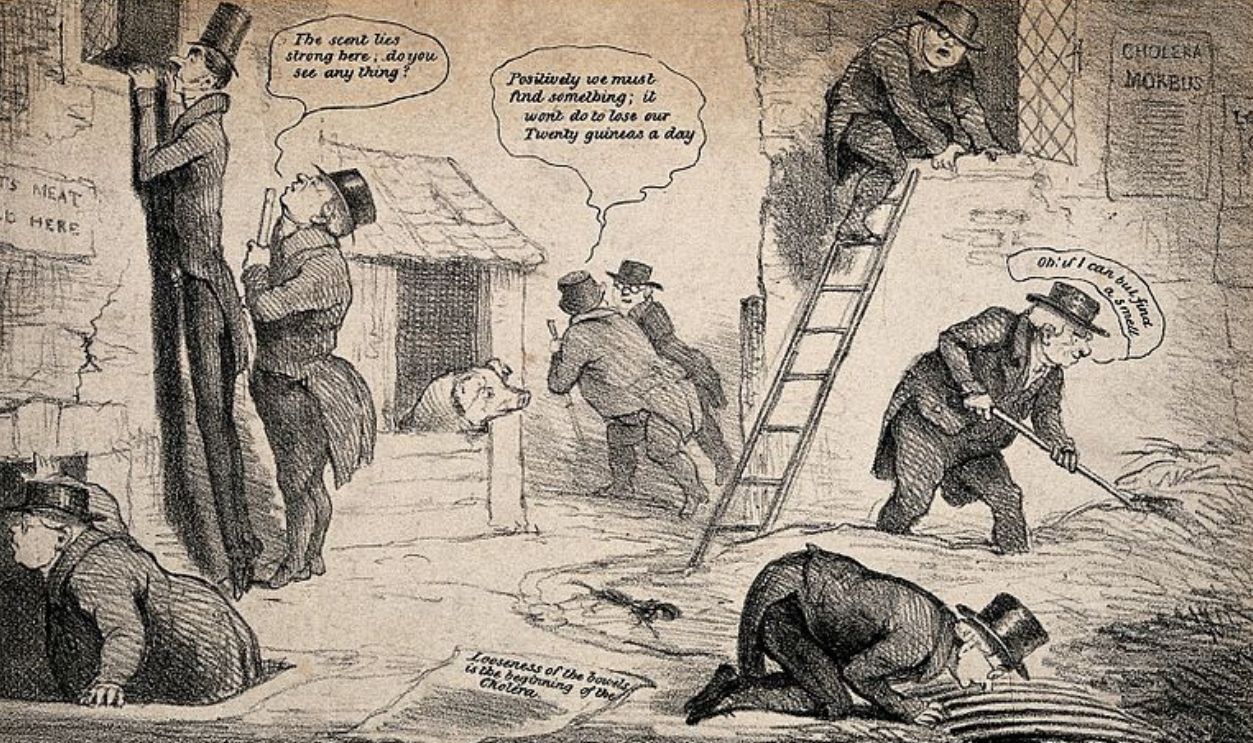

Cholera Strikes

London went through three really bad cholera outbreaks. There were 6,536 deaths in the year 1831, followed by 14,137 in 1848-49, and 10,738 in 1853-54. Back then, doctors mistakenly thought that disease spread from "miasma"—basically, nasty smells from rotting material.

Robert Seymour, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Seymour, Wikimedia Commons

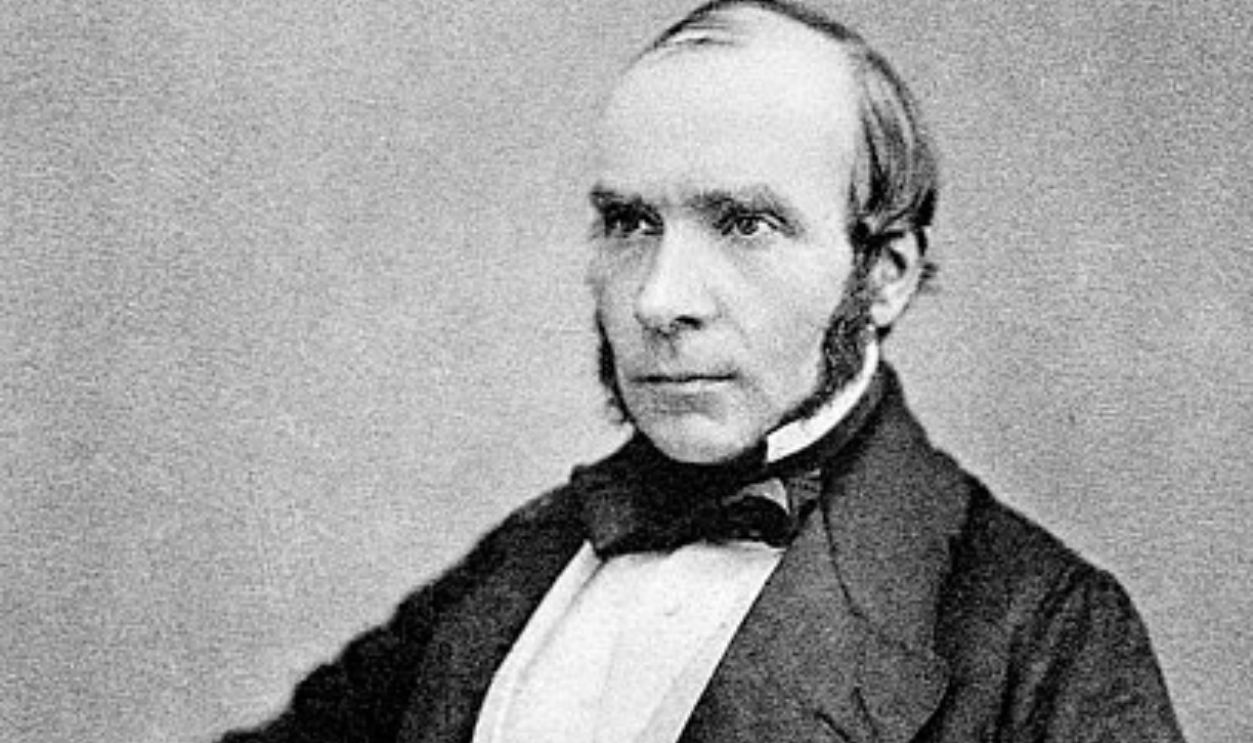

Snow's Discovery

Dr. John Snow figured out that cholera deaths were connected to water companies during the 1848–49 outbreak. Then in 1854, on Broad Street, he took off the handle of a water pump, which stopped people from using the contaminated water. This proved that the disease spread through water.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Failed Solutions

As the smell of untreated sewage in the River Thames began worsening, the British government set up various measures to reduce the stench. This failed effort included pouring substances like carbolic acid, lime chloride, and chalk lime into the river.

Punch Magazine, Wikimedia Commons

Punch Magazine, Wikimedia Commons

Bazalgette's Role

Later, in August 1849, Joseph Bazalgette joined the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers as an assistant surveyor. Following the death of head engineer Frank Foster in 1852, Bazalgette took over and developed systematic plans for London's sewers.

Lithographer: George B. Black, Wikimedia Commons

Lithographer: George B. Black, Wikimedia Commons

Initial Plans

By June 1856, Bazalgette had completed his plans for a network of smaller local sewers that would flow into larger ones. He designed pipes three feet wide, connecting to main sewers eleven feet high, featuring both northern and southern outfall systems.

Z22, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Z22, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Summer Crisis

However, in June 1858, the heat cranked up, hitting around 34–36°C in the shade and 48°C in the sun. With the Thames water levels low and the scorching temperatures, a nasty smell from all the sewage piled up along the riverbanks. It was unlike anything anyone had seen before.

Royal Retreat

One notable incident occurred during this time. It seems that Prince Albert, along with Queen Victoria, tried a Thames leisure cruise but were forced to leave in a matter of minutes because of the overpowering stink. The media soon started calling it what it was: "The Great Stink".

Alexander Bassano, Wikimedia Commons

Alexander Bassano, Wikimedia Commons

Parliament Disrupted

Even though the curtains were soaked in lime, the smell badly affected the Parliament. MP John Brady said the members could not use the library or committee rooms. Officials even spent £1,500 a week spreading lime to cover the smells.

Alexander Bassano, Wikimedia Commons

Alexander Bassano, Wikimedia Commons

Press Reaction

Newspapers around the nation reported on the issue, expressing public fury. According to the City Press, the stink was "unforgettable," highlighting how unbearable it had gotten. Also, The Standard called the Thames a "pestiferous and typhus breeding abomination".

Political Action

Benjamin Disraeli introduced urgent legislation in response to the overwhelming crisis caused by the Great Stink. He described the Thames as "a Stygian pool," while his Metropolitan Local Management Amendment Bill secured £3 million for Bazalgette's sewer plan through household taxes.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

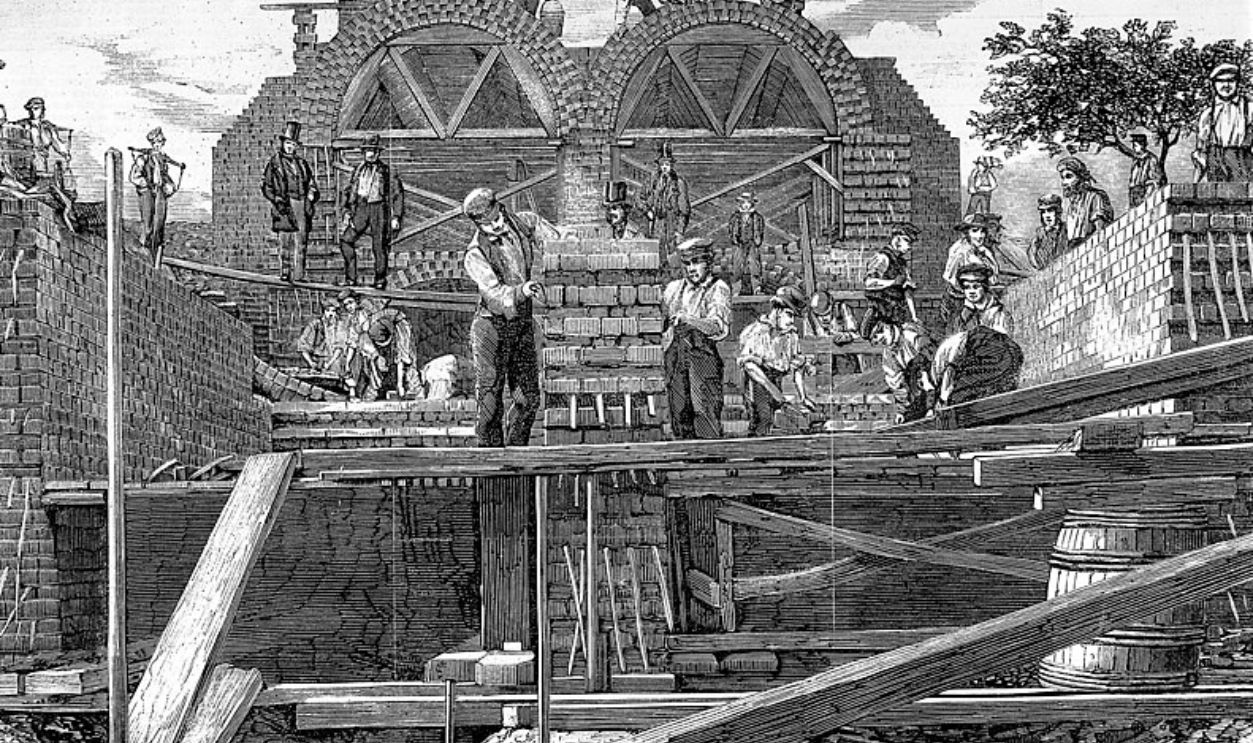

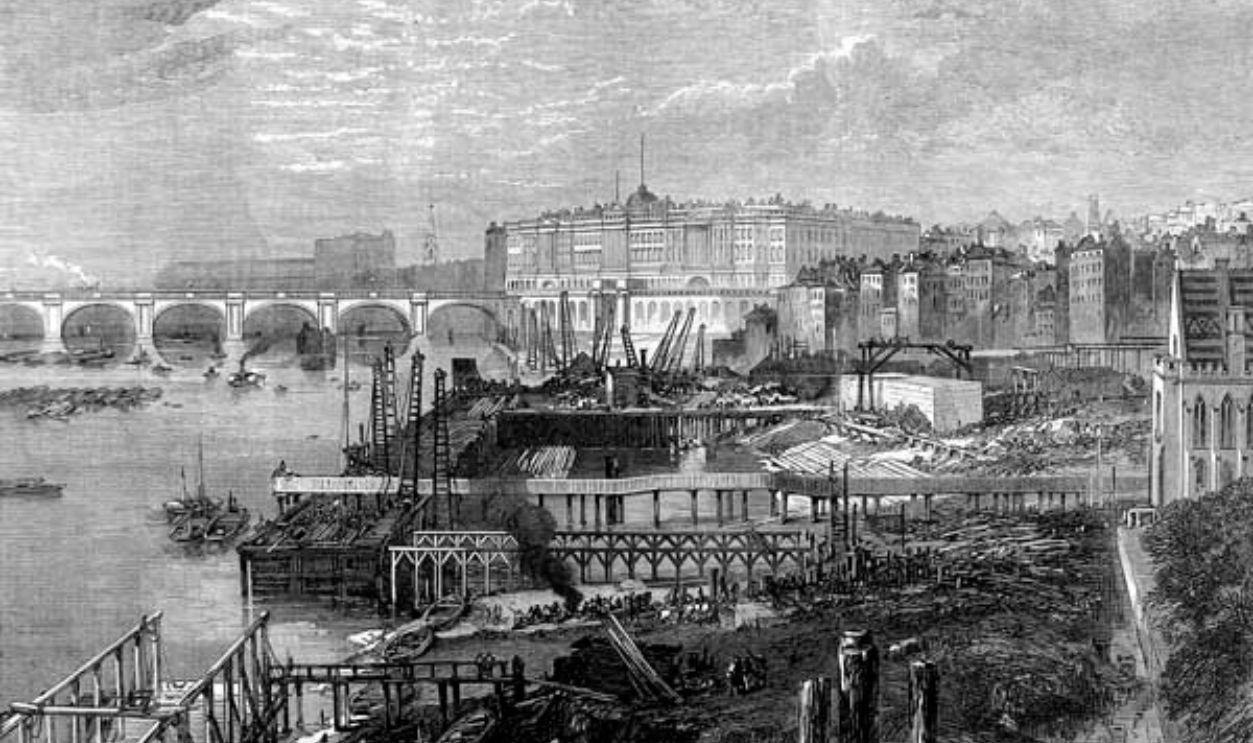

Construction Begins

In 1859, work started on 1,100 miles of street sewers, feeding into 82 miles of main interconnecting sewers. This monumental project was led by civil engineer Bazalgette. Around four hundred draftsmen worked on detailed plans for London's new drainage system.

The Illustrated London News, Wikimedia Commons

The Illustrated London News, Wikimedia Commons

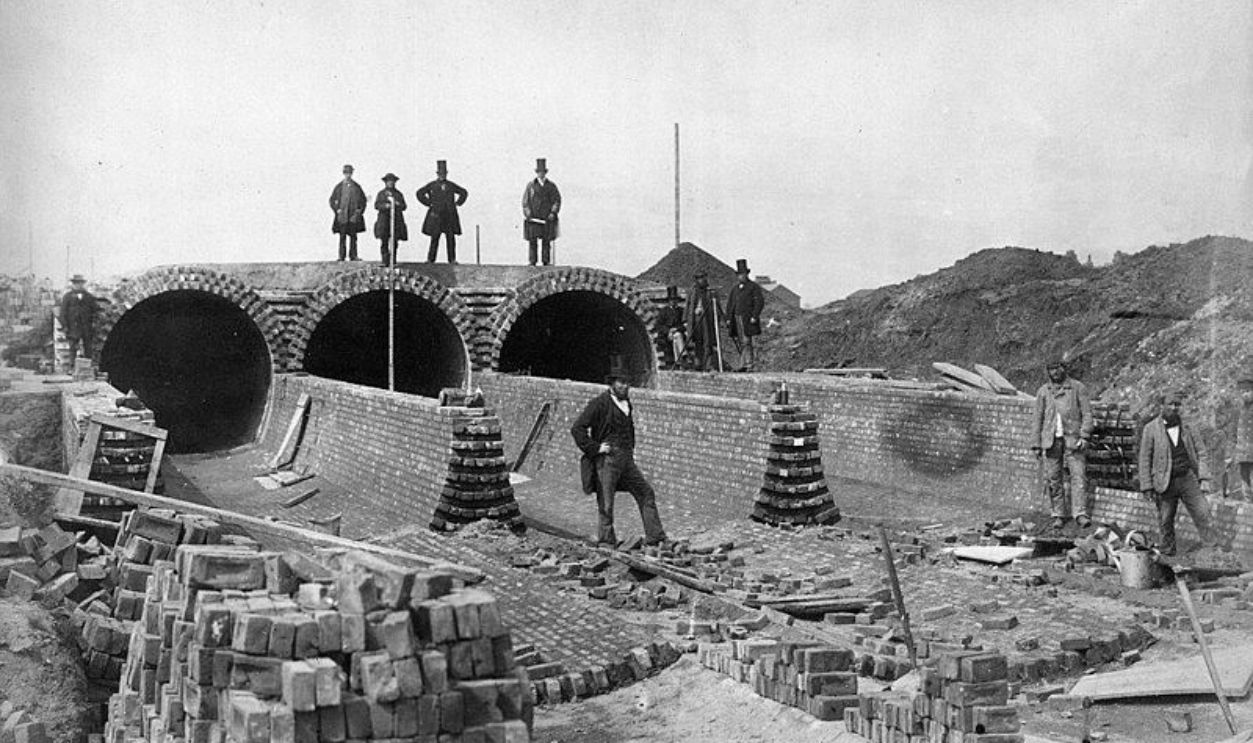

Engineering Challenges

Joseph Bazalgette faced challenges in constructing London's new sewer system, particularly in low-lying areas like Lambeth and Pimlico. He implemented a pumping station system designed to lift sewage from these lower areas into the main sewer lines to address this issue.

Adam Cuerden, Wikimedia Commons

Adam Cuerden, Wikimedia Commons

Quality Control

To ensure quality work, Bazalgette also implemented strict testing of Portland cement, which is more effective than standard cement, for construction. His "draconian" and "elaborate" quality control systems forced manufacturers to improve their products while setting new standards for public works projects.

Punch magazine, Wikimedia Commons

Punch magazine, Wikimedia Commons

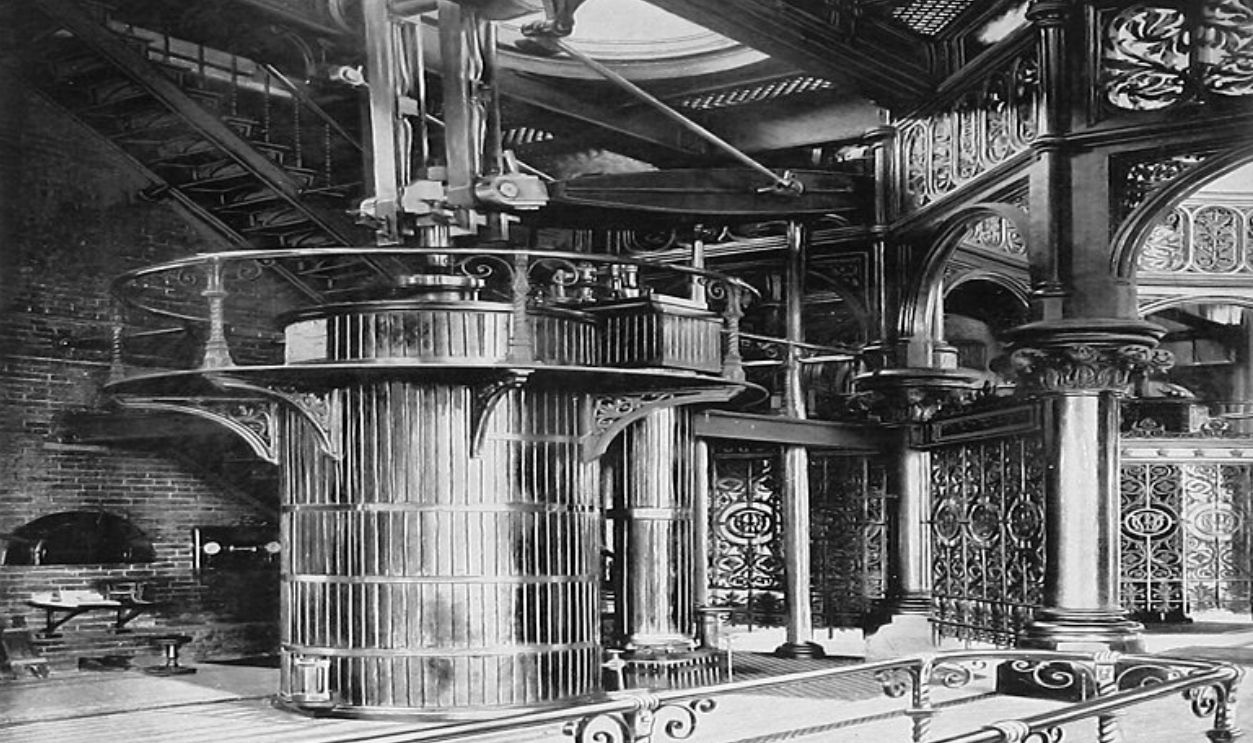

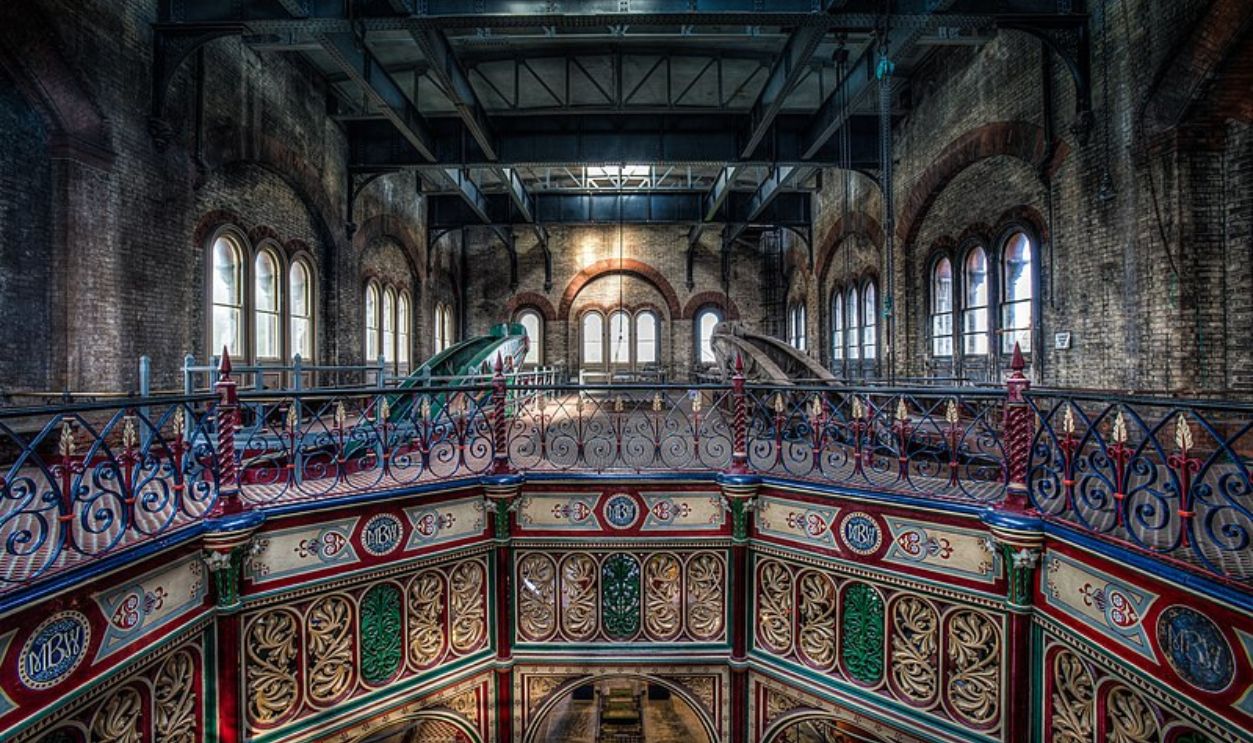

Southern System

The Southern Outfall Sewer System transported waste from Putney, Wandsworth, and Norwood to the Crossness Pumping Station. At Crossness, sewage was lifted from lower-lying areas into the main outflow sewer. The pumping station had powerful steam-driven pumps.

Various photographers for Cassell & Co., Wikimedia Commons

Various photographers for Cassell & Co., Wikimedia Commons

Northern Complexity

The construction of London's Northern Outfall Sewer System served approximately two-thirds of the city's population. Numerous obstacles, such as clogged city streets, severe winters, and torrential rains, hindered the technical work on this big project.

Illustrated London News, Wikimedia Commons

Illustrated London News, Wikimedia Commons

Embankment Creation

Along the Thames River, Bazalgette constructed three substantial embankments: the Victoria Embankment, the Albert Embankment, and the Chelsea Embankment. The embankments collectively reclaimed 52 acres from the Thames, allowing usable land to be expanded.

Leonard Bentley, Wikimedia Commons

Leonard Bentley, Wikimedia Commons

Project Completion

So, by 1875, the construction of London's modern sewer system was finally completed. The building reportedly used about 318 million bricks and 880,000 cubic yards of concrete. Also, the project ended up costing around £6.5 million, which was more than what was originally projected.

The Illustrated London News, Wikimedia Commons

The Illustrated London News, Wikimedia Commons

Health Improvements

After the completion of Bazalgette's sewer system in London, the city did not really experience another major cholera outbreak. The effectiveness of this system was particularly made evident during the cholera epidemic of 1866, which resulted in 5,596 deaths.

Wellcome Library, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Wellcome Library, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Situation At The East End

It should be noted that these fatalities occurred only in areas not yet connected to Bazalgette's new sewage infrastructure. They were limited to a section of the East End between Bow and Aldgate. Allegedly, 93 percent of the deaths took place around this area.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

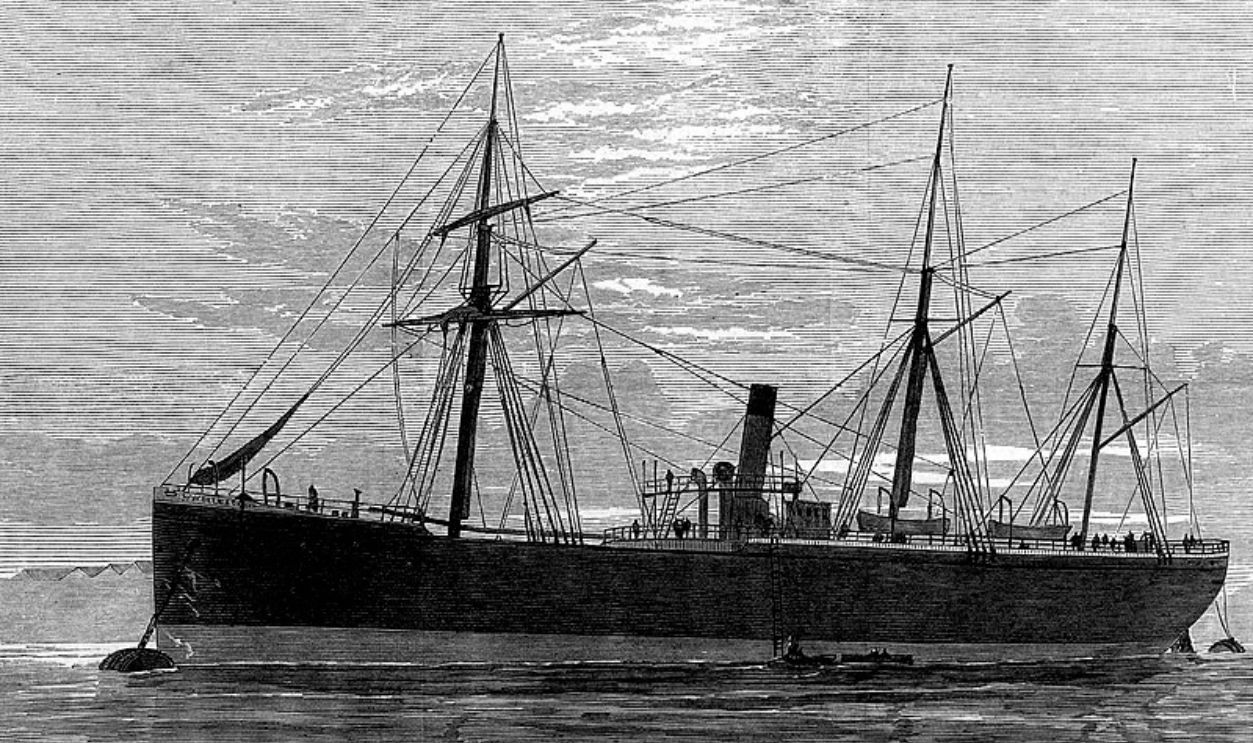

Ship Tragedy

The SS Princess Alice, a passenger paddle steamer, tragically sank after colliding with the collier Bywell Castle on the Thames. This 1878 disaster resulted in deaths, which caused the British news to question whether some of the deaths were caused by sewage.

Josiah Robert Wells, Wikimedia Commons

Josiah Robert Wells, Wikimedia Commons

System Upgrades

In response to this, in the 1880s, authorities began purifying sewage rather than disposing of raw trash at Crossness and Beckton. Sometime in 1887, six specialized sludge boats were commissioned to transport treated sewage sludge to the North Sea until 1998.

Peter Scrimshaw, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Peter Scrimshaw, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Historic Achievement

According to historian John Doxat, Bazalgette "probably did more good and saved more lives than any single Victorian official". This was because of the capital's integrated and fully operational sewer system and the resulting decline in cholera occurrences.

Prioryman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Prioryman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons