“Oh, The Humanity”

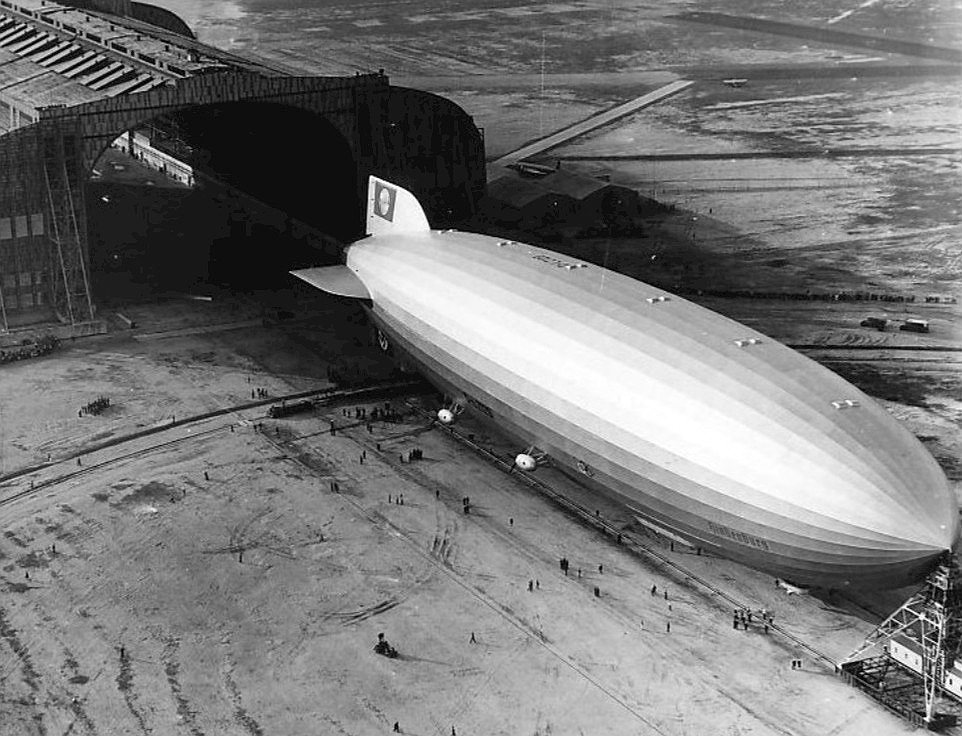

In the late afternoon of May 6, 1937, Manhattanites who looked to the sky would’ve been treated to a nearly unbelievable sight: A gleaming, giant silver Zeppelin—the biggest in the world—flying above them on its way to land in Lakehurst, New Jersey.

People rushed out to the street just to catch a glimpse of it, not knowing they were about to play a small part in one of aviation’s worst disasters.

A “Terrific Crash”

Just a few hours later, as the LZ 129 Hindenburg began to descend to its destination, it burst into flames and crashed to the ground, its structure crumbling almost immediately. Not only did it take the lives of 35 people, it effectively ended the airship era in travel.

And perhaps the strangest part? No one really knew why it happened—though recently discovered documents reveal the untold, chilling truth about that fateful evening.

Wide World Photos, Wikimedia Commons

Wide World Photos, Wikimedia Commons

The Airship

For years, the image of the large silver airship, or Zeppelin, captivated the world, only for its reputation to crash and burn simultaneously with the Hindenburg. To uncover the truth about the Hindenburg disaster, we have to understand the airship itself—and how it became such a popular form of travel despite what we now can see are blatant vulnerabilities.

Associated Press, Wikimedia Commons

Associated Press, Wikimedia Commons

What IS A Rigid Airship?

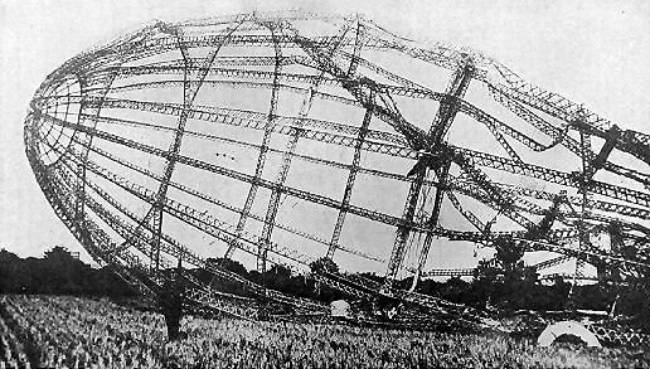

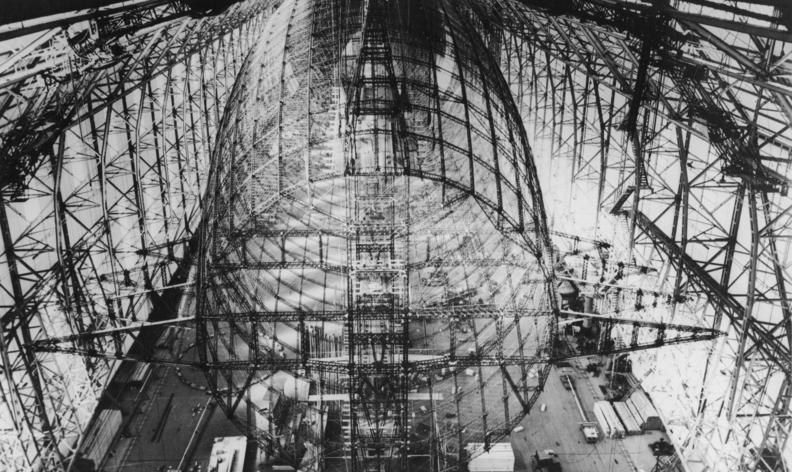

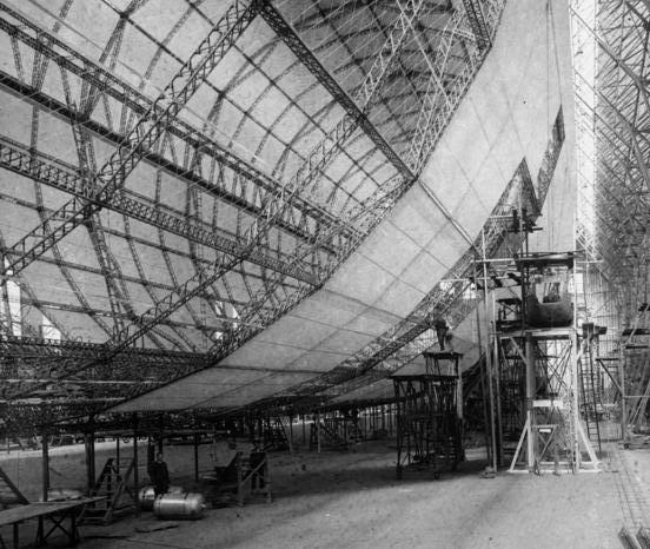

The Hindenburg was a rigid airship. To simplify a very complicated topic, while airplanes depend on wind flow and lift from the wings, airships float thanks to their envelopes being filled with a lifting gas, and the difference in density between the lifting gas and surrounding air.

Rigid Vs Blimp

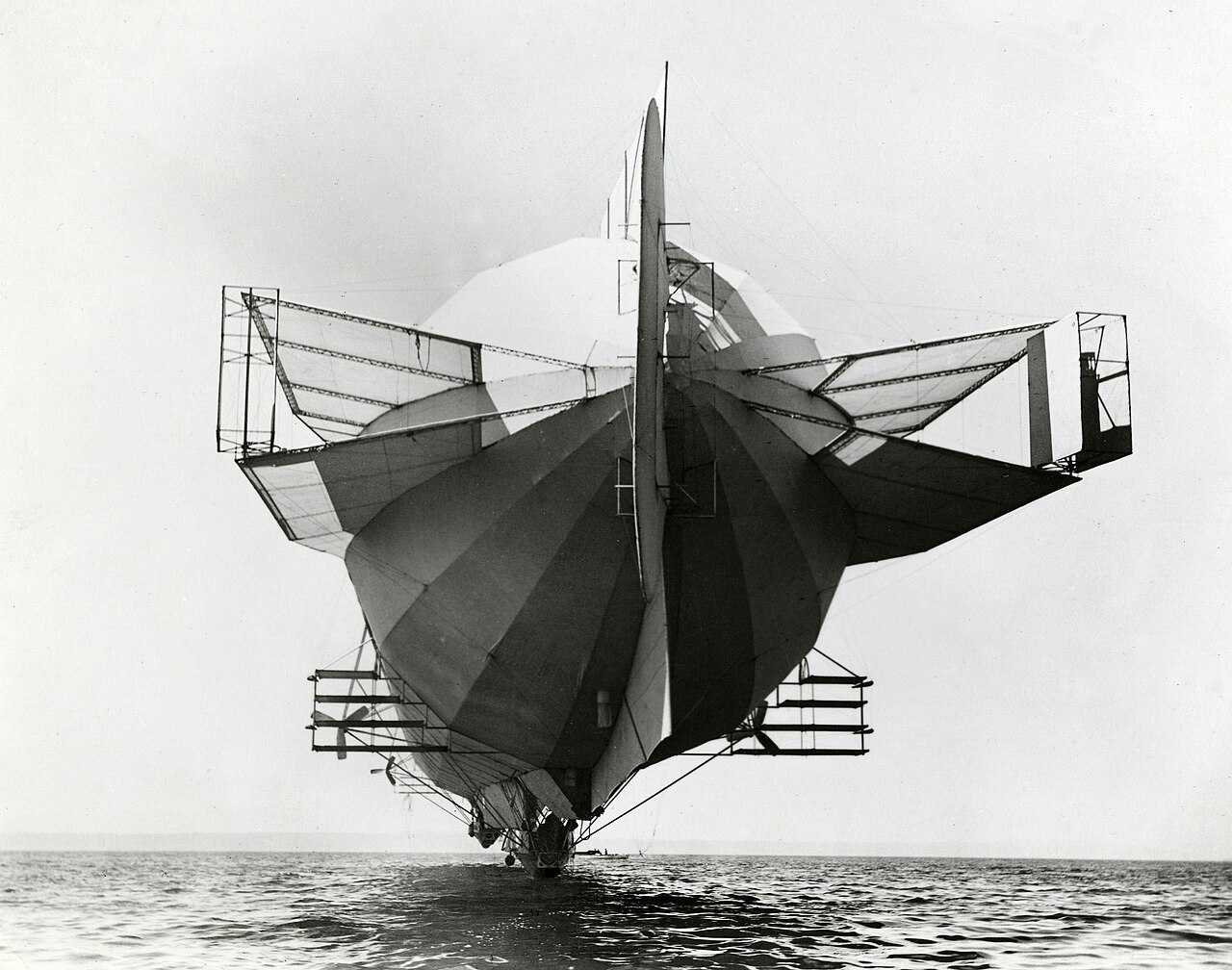

A rigid airship like the Hindenburg is a type of airship whose envelope is supported by an internal framework, as opposed to simply the lifting gas itself, as in a blimp. For years, the lifting gas used in many rigid airships was highly-flammable hydrogen—and this led to its fair share of problems.

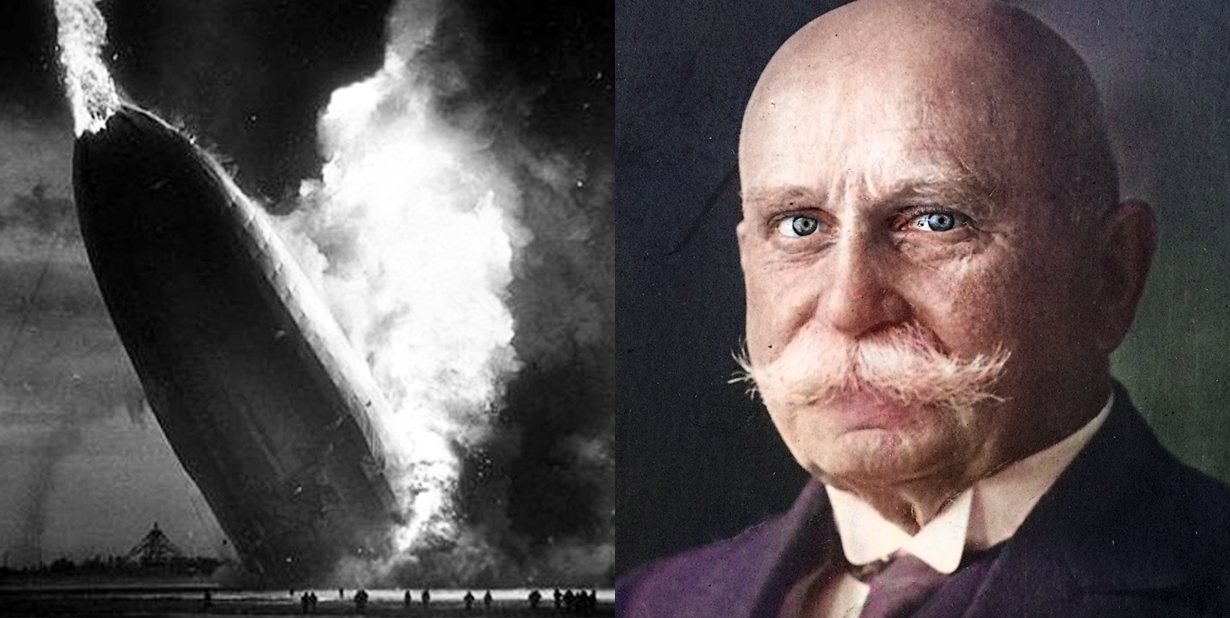

The Zeppelin

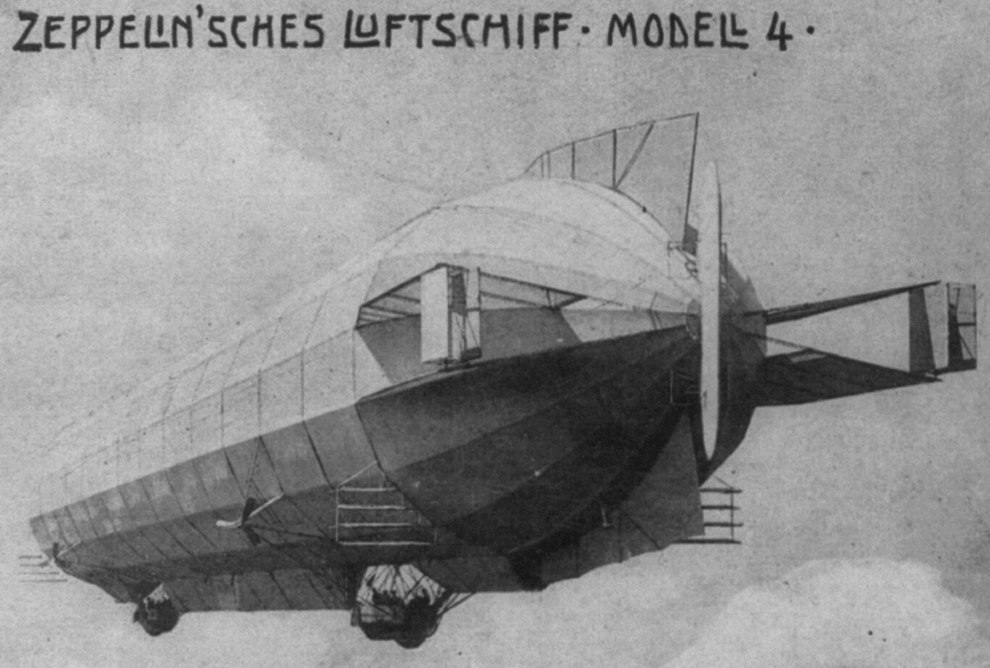

In a case of antonomasia, many preferred to call rigid airships by the name “Zeppelin” instead—and it’s no wonder. Though several other inventors worked to patent their own designs for rigid airships, German general Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin was the first to build a successful one, the LZ 1, in 1900.

Nicola Perscheid, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Nicola Perscheid, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Trial & Error

Multiple models and tests, some failed, some successful, followed, and eventually, Count von Zeppelin sold one of his airships to the German army, sparking an interest in the craft—for better, or for worse.

Test Runs

The Germans wanted an airship that could fly for 24 hours straight, so the Count designed a bigger and better model for them, the LZ 4—but during a test flight, something terribly ominous happened. It broke from its moorings, got blown into a tree, and caught fire in front of a crowd of approximately 50,000. The reaction to this incident was surprising.

George Grantham Bain, Wikimedia Commons

George Grantham Bain, Wikimedia Commons

Shock & Awe

Instead of breaking the public’s confidence in the airship, they actually rallied around it. German people raised 6 million marks to help Count von Zeppelin rebuild—and that’s not all it did.

The Passenger Airship

One major precursor to the Hindenburg disaster was the transition from military to passenger usage for the airships. The massive interest in airships, including the wave of attention that followed the LZ 4 disaster, actually spurred Count von Zeppelin’s business manager to push them as passenger ships.

Though the Count himself was reportedly not interested in such a usage, his company nonetheless had airships running for pleasure cruises and travel within Germany. But after WWI, they found themselves in a pickle.

Unknown Author, Wikipedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikipedia Commons

Bigger Isn’t Better

As part of the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany wasn’t allowed to produce airships over a certain size, greatly limiting the potential of Zeppelin’s fleet. However, the Count’s company, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, eventually formed a partnership with Goodyear which allowed them to build a craft for the US Navy, saving Luftschiffbau Zeppelin from certain doom.

Transatlanticism

At the time, travelers who wanted to cross the Atlantic were bound to travel by sea—however, as one could imagine, the popularity of and confidence in ships traveling that route had waned greatly after the Titanic. Airplanes didn’t yet have the range to complete a non-stop transatlantic flight, so the chairman of Luftschiffbau Zeppelin set his sights on building airships capable of making the journey.

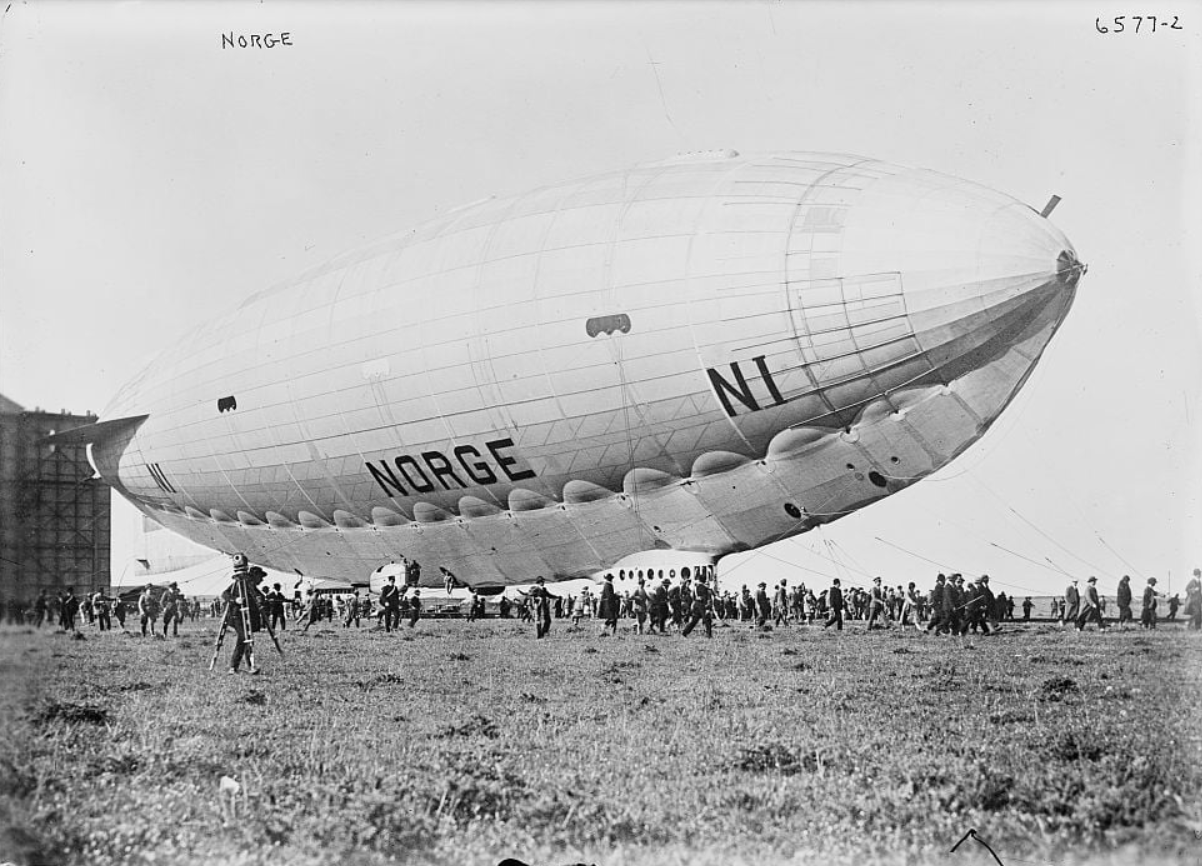

Graf Zeppelin

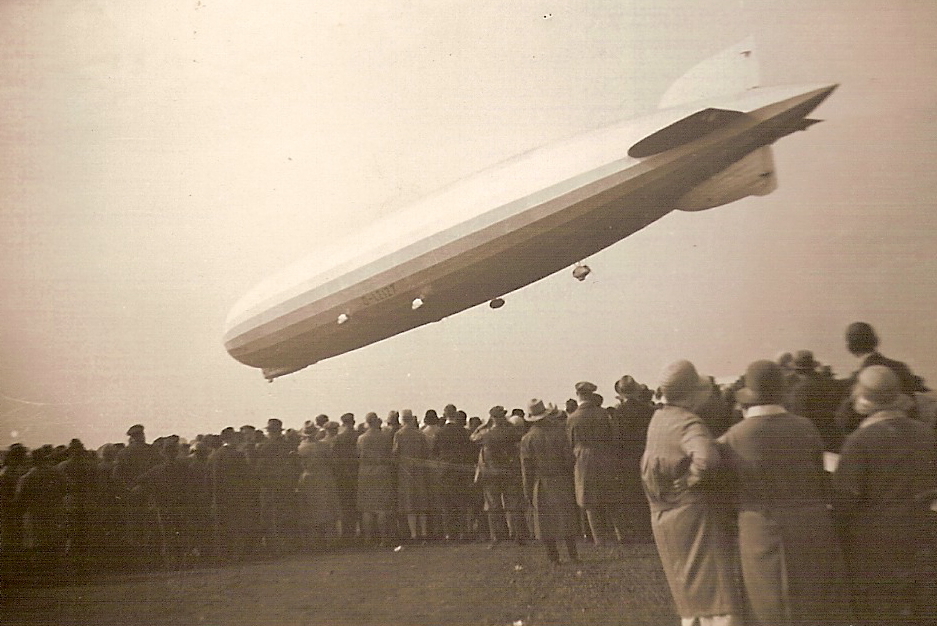

The new generation of airship was called the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin, and began operating under airline DELAG as the first non-stop transatlantic passenger flights in 1928. Flights began to regularly travel from Frankfurt to NAES Lakehurst in New Jersey, and other routes between Germany and Brazil were later added.

San Diego Air and Space Museum, Pictyl

San Diego Air and Space Museum, Pictyl

A New Way To Travel

In the inter-war years in Germany, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin’s airship was a rare success story. The LZ 127, it seemed, was the way of the future—but progress marches on, and they wanted to take things up a notch.

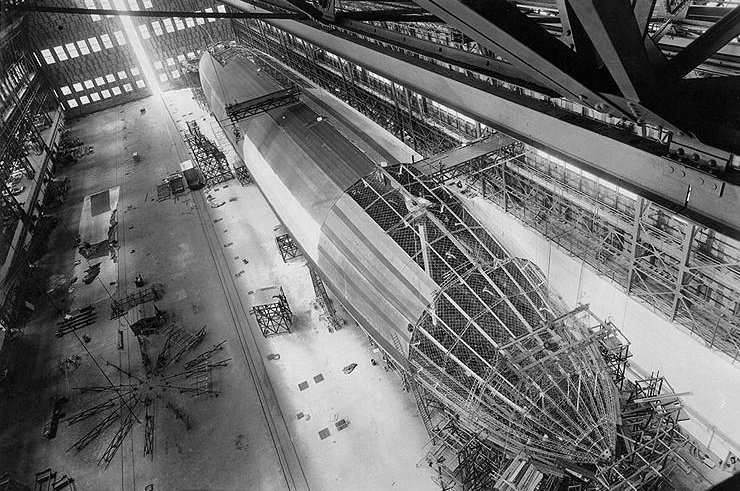

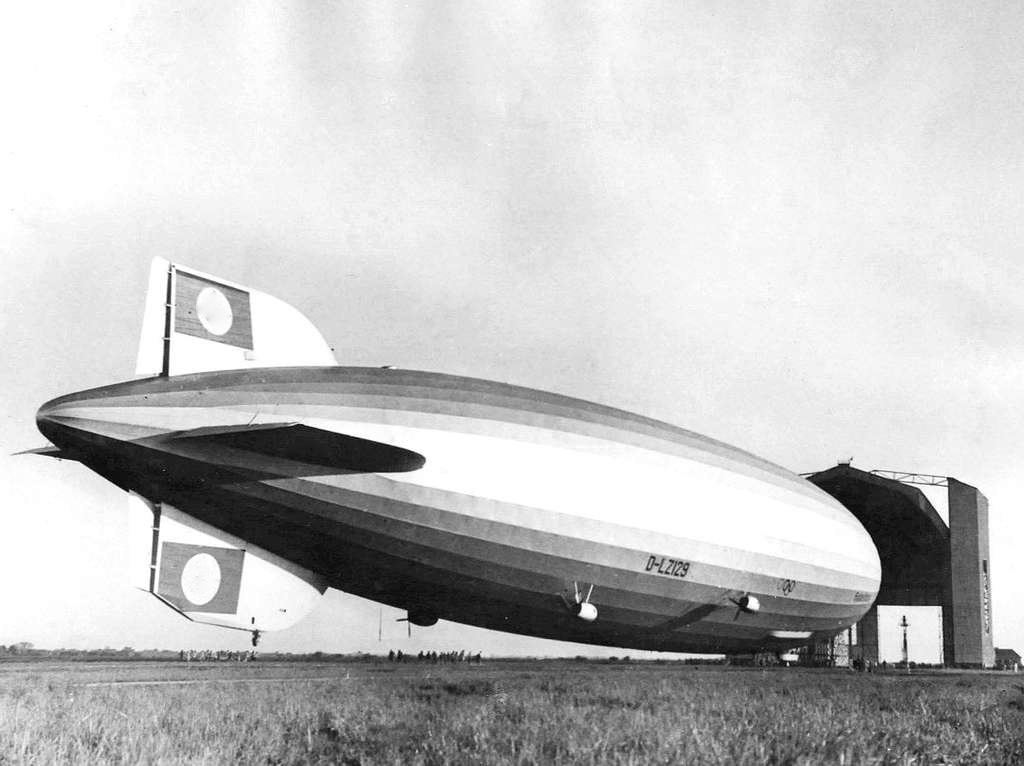

LZ 129 Hindenburg

Calls for a bigger, better Zeppelin airship began almost immediately after the success of the LZ 127, but plans for the 128 were halted in their tracks thanks to an air disaster in Britain, where an airship powered by hydrogen caught fire. New designs were drawn up involving the use of helium instead—but you know what they say about the best laid plans.

Grombo, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Grombo, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Battle Of The Gases

Manufacturing of parts began in 1931, and assembly began in 1932. Though the LZ 129 had been designed with helium in mind, thought to be the safest possible lifting gas for such a use, the company eventually had to admit defeat. Not only was helium wildly expensive and rare, there was also a US ban on the export of the gas.

Back To The Drawing Board

The company hoped and campaigned for the US to change the rules, but there was no such luck. The engineers went back to the drawing board. Ultimately, despite previous disasters, they re-designed the LZ 129 to use highly-flammable hydrogen instead.

Bundesarchiv, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Namesake

The LZ 129 took four years to complete, finishing in 1936, and was named for Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, the long-serving German President who’d passed on two years earlier. Not only did he lend his name to an airship that ended in a disaster so large, it eclipsed his legacy, but his rule also led to the political instability that allowed Hitler to take power.

Sorry, Paul!

Bundesarchiv, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Test Flights

Finally, in 1936, the LZ 129 Hindenburg flew its maiden test flight successfully, which it followed up with a passenger and mail flight on March 23. And then, things got dicey. Against the wishes of Luftschiffbau Zeppelin’s chairman Hugo Eckener, the LZ 129 was forced to make a flight as part of a Nazi Party propaganda campaign.

Imagine if the ship had gone down then, instead? How the course of history might have changed?

Bundesarchiv, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Maiden Voyage

After the party had successfully used the LZ 129 in their campaign, Eckener was able to wrest control of the airship back from the propaganda ministry and prepare for its first transatlantic flight to Rio de Janeiro. Though the trip there and the return were both successful, engineers took note of potential problems.

The Beta Version

After the maiden voyage, the team behind the LZ 129 had to address a multitude of potential problems, from carbon buildup to stuck open gas valves to engine failure. They worked hard to get it on, addressing them both on the fly and back at the hangar. Finally, the LZ 129 Hindenburg was officially ready to go into service.

Robert Yarnall Richie, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Yarnall Richie, Wikimedia Commons

So Fast

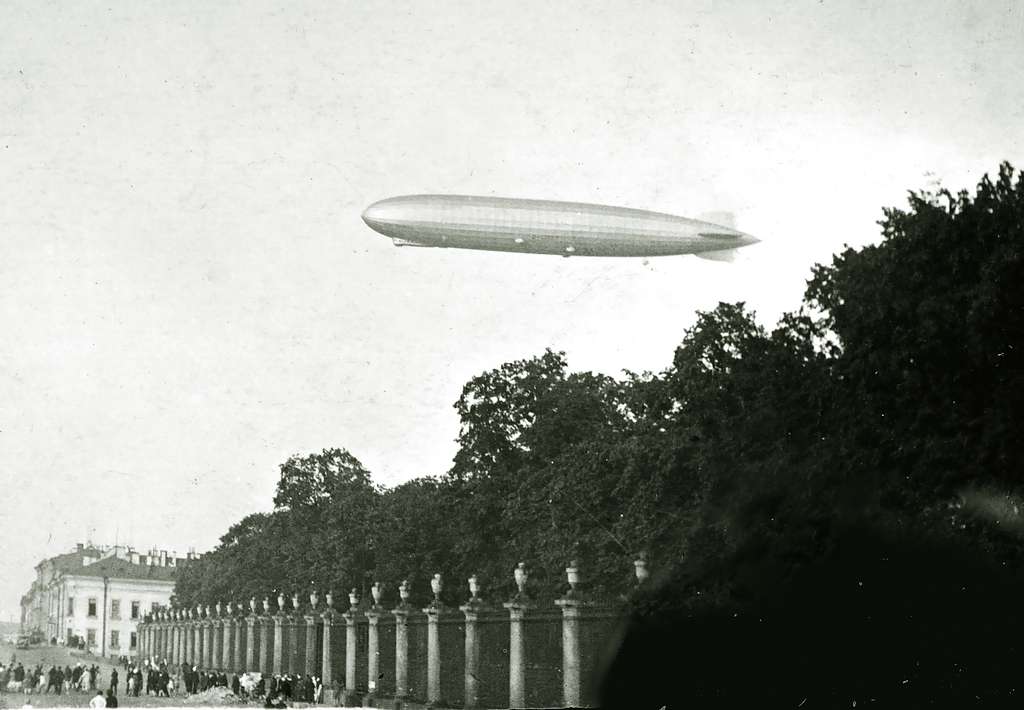

Throughout 1936—the airship’s first and only full year of service—the LZ 129 made a total of 17 round trips across the Atlantic, including 10 to the US and seven to Brazil. One of these made record time from Frankfurt to Lakehurst, completing the round trip in 98 hours, 28 minutes.

So Smooth

People marveled at how stable it was, remarking that a pen or pencil could be stood on end without falling on one of the airship’s tables. Others claimed that the engines and operations were so quiet that they hadn’t even noticed the airship taking off while on board. Soon, word of the ship began to attract notable people.

The Millionaires’ Flight

Celebrities including politicians, entertainers, and athletes flocked to board the Hindenburg. It was called into service by the German government again to take fly over the Berlin Olympics’ opening ceremonies, and one short flight in New England was dubbed the “Millionaires’ Flight” for attracting figures like Nelson Rockefeller.

Associated Press, Wikimedia Commons

Associated Press, Wikimedia Commons

An “Unremarkable” Flight

After undergoing some alterations over the winter in late 1936 and early 1937, it was time for the LZ 129 to return to the air. After a round trip to Brazil, it set out for its first round trip of the year to the US, beginning May 3, 1937. Despite strong winds, the crew noted that the trip across the Atlantic was quite unremarkable.

A Quiet Ride

It was also a quiet flight for the passengers. Though it had a capacity of 70, there were only 36 on board—but for good reason, The coronation of King George VI was approaching, and the airship expected to be at full capacity for the flight back to Europe.

Killing Time

As ground crew alerted the Hindenburg’s captain, Max Pruss, of bad weather in the area where they were supposed to land, he came up with a variety of ways to entertain both the passengers on board and people on the ground. As mentioned earlier, he decided to fly over Manhattan, creating a massive spectacle, and then took his passengers over the New Jersey coastline to admire it. Sadly, for many, it would be their final memories.

Andrey Zarembo, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Andrey Zarembo, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Cleared For Landing

Finally, Captain Pruss was alerted that the airship was cleared for landing at NAES Lakehurst. Thanks to multiple delays over the trip, they were almost half a day behind schedule. At approximately 7:00pm on May 6, 1937, the LZ 129 Hindenburg approached the landing site and prepared to throw down a line, which would be winched down, allowing it to land.

That’s when it faced the first of many, many problems.

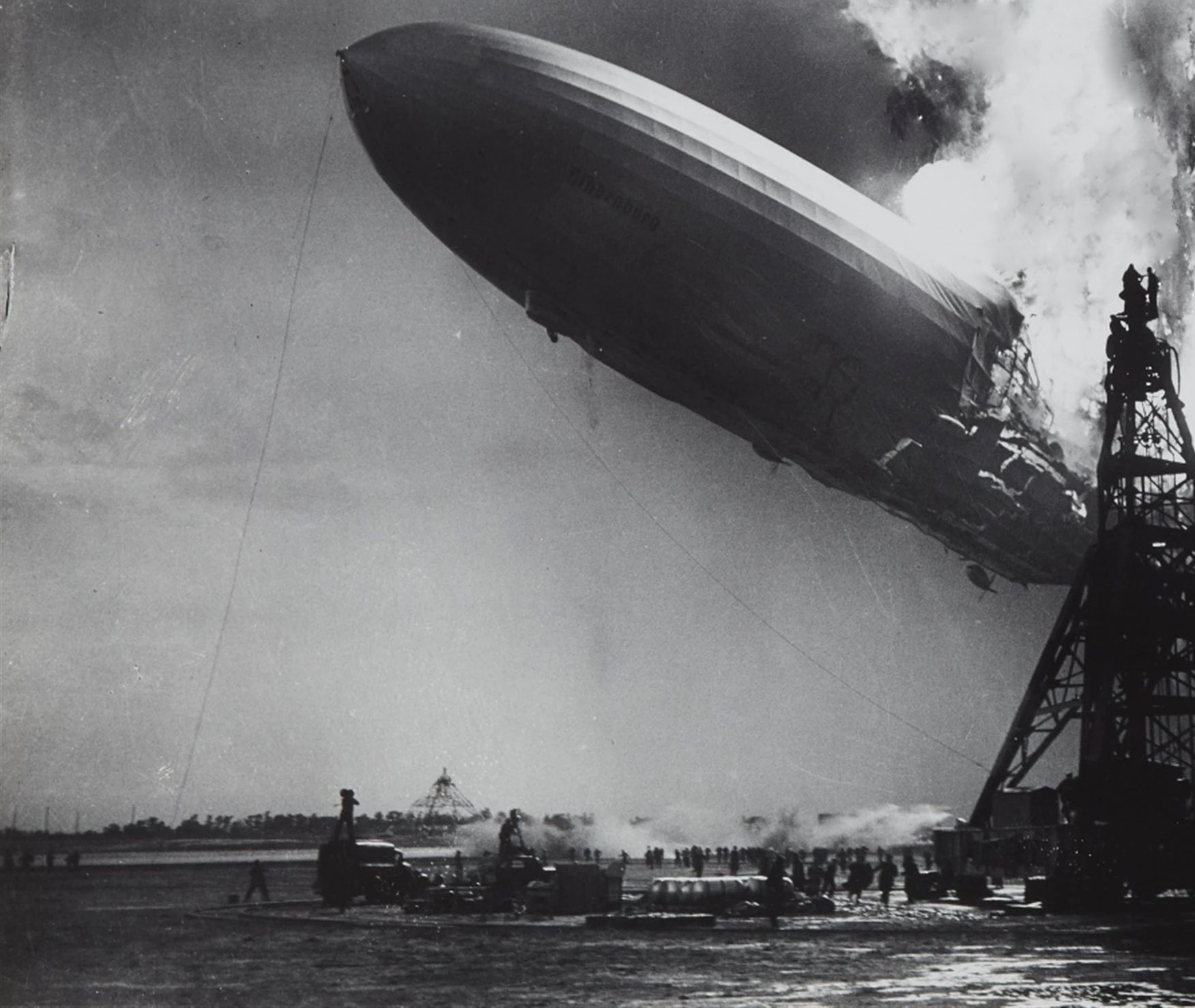

A Recipe For Disaster

First, the ground crew wasn’t ready. Then, the winds changed directions sharply, forcing Captain Pruss to make sharp turns and circle back. Finally, the airship’s crew were able to throw their lines down. It was at this point that people on the ground began to report seeing flames at different points around the ship, though many accounts differed.

One thing is for certain: By 7:25pm, the LZ 129 Hindenburg was on fire.

The Disaster

On board, some passengers reported hearing what sounded like a detonation. Those on the ground watched helplessly as flames quickly engulfed the craft, traveling from gas cell to gas cell and igniting the highly flammable hydrogen used onboard. The stern imploded, causing further explosions. It sank as the bow floated upward in a towering plume of flame.

An Unforgettable Image

As the stern then hit the ground, the bow came down to meet it, before fire stripped it down to its skeleton in a matter of mere seconds. As the bow hit the ground, the entire structure crumbled. Within just about 90 seconds, the world’s largest airship was gone. People on the ground were, understandably, absolutely hysterical.

The Footage

Though there were reporters on the ground with both still and film cameras, there’s no existing footage of the initial fires that broke out. However, there is film footage of the scene described above, starting around where the stern begins to drop. It’s 30 of the most harrowing seconds of video ever recorded, and features the sounds of onlookers screaming as they watched the destruction.

Reports From The Ground

Reporters there to welcome the ship were forced to quickly pivot and do their best to record what was happening in front of their eyes. As Chicago radio reporter Herb Morrison watched helplessly, he tried his best to describe what he was seeing through the terror in his heart for the people on board. His comments were preserved in a recording from that day, and they’re utterly terrifying.

The Recording

In the recording, Morrison is heard saying: “It’s fire and it’s crashing! […] This is the worst of the worst catastrophes in the world! Oh, it’s crashing…oh, four or five hundred feet into the sky, and it’s a terrific crash, ladies and gentlemen. There’s smoke, and there’s flames, now, and the frame is crashing to the ground, not quite to the mooring mast. Oh, the humanity, and all the passengers screaming around here!”

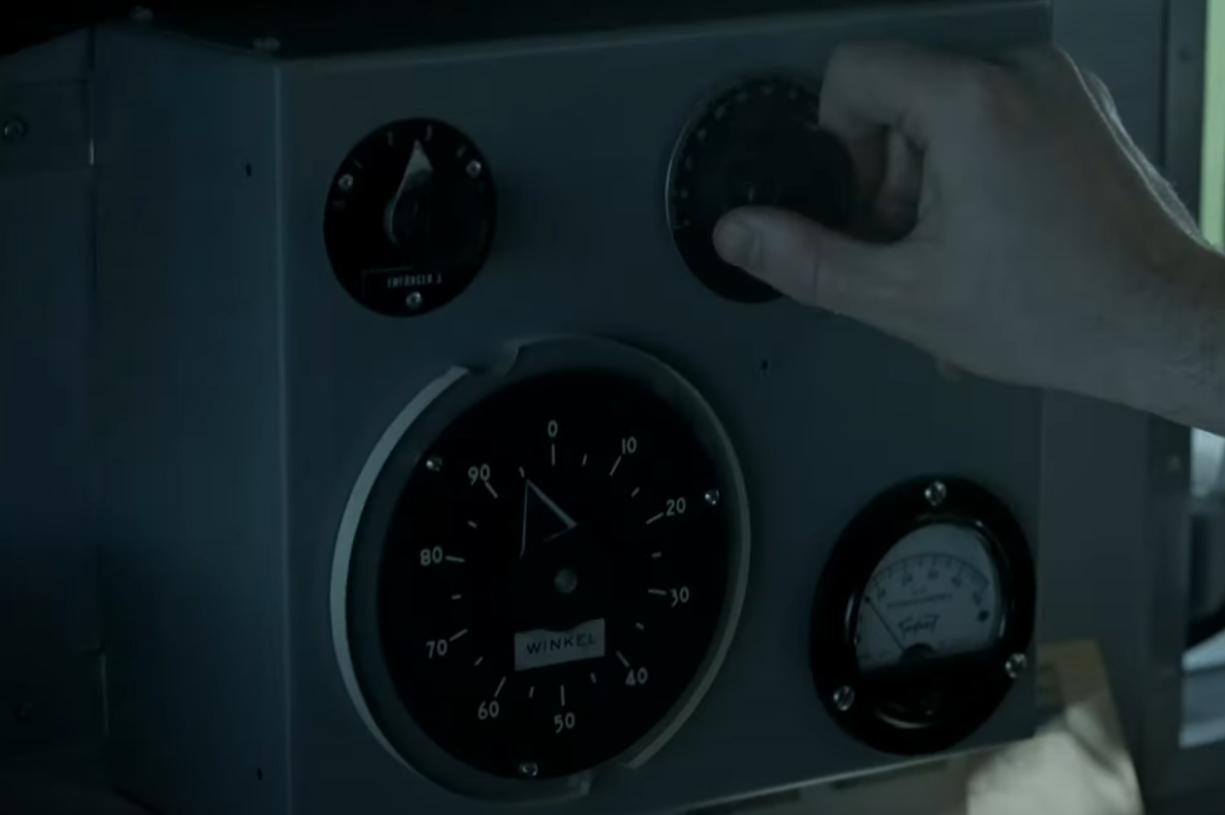

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

The Origin Of A Phrase

Did you notice anything about Morrison’s reporting? Specifically, his use of the phrase, “Oh, the humanity”? Though it’s now a more common turn of phrase, it actually had its origins in that very moment and that very recording. But it didn’t immediately catch on after audiences watched the initial footage of the disaster.

The audio wasn’t paired with the film footage initially. It was preserved and only added decades later, and the phrase caught on. And Morrison would come to rue his words.

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

Looking Back

Nearly immediately after his initial, borderline hysterical speech about the crash, Morrison learned that some had survived the crash. Upon hearing the news, he said, “I hope that it isn’t as bad as I made it sound at the very beginning”.

Years later, reflecting on his “Oh, the humanity” moment, Morrison recalled that he’d only yelled it because he believed everyone on board had perished. For better or worse, Morrison’s eyewitness report became one of the most remarkable broadcasts in the history of radio.

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

The Rescue Efforts

Though the sheer devastation and horror of the scene before them made many on the ground think that the crash had taken the lives of everyone on board, one wise Navy officer—himself a survivor of a remarkable airship disaster—proved the importance of composure and bravery in the face of tragedy.

Chief Petty Officer Frederick J "Bull" Tobin, who was in charge of the Navy’s landing party, had survived the USS Shenandoah disaster, was ready to jump into action.

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

“Stand Fast”

The Navy’s landing party looked on in fear as flames beat around the site of the wreckage, only to be stirred to action by an unforgettable order by Tobin: “Navy men, stand fast”! His command worked, and they rushed to form a rescue operation for those who survived the fire and crash.

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

The Survivors

Anyone who has viewed footage of the disaster would rightfully wonder how anyone survived. However, since the craft was flying so low in preparation for mooring, some were able to jump out as it started to catch fire. Others were sequestered in areas that were safe from the fire, and were able to escape at the last minute.

For many, it was a matter of luck—those on the starboard side were trapped as the airship rolled, while those on port had better chances.

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

The Count

Ultimately, there were 35 fatalities and 62 survivors, with one other fatality on the ground. 13 of 36 passengers perished along with 22 of 61 crew. The ground fatality was a member of the ground crew. Though there was a remarkable number of survivors, considering the terrifying circumstances, many were burned very badly.

Some of the fatalities perished in the fire, while others jumped when the airship was still too high in the air. Smoke and debris were other contributors to the number of fatalities.

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

The Investigation

As news spread about the Hindenburg disaster, the loudest question was about how it had happened—and since there was so little evidence left, and so many differing accounts as to where on the airship the fire had broken out, it was hard to pin down a potential cause—creating one of the most compelling mysteries of the 20th century.

And, as with any mystery, everyone had a hypothesis of their own.

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

Sabotage

Luftschiffbau Zeppelin chairman—and thorn in the Third Reich’s side—Hugo Eckener was among the first to speculate about sabotage, as he’d received threatening letters, but that was also a theory he disavowed as he learned more about the disaster. Still, to many, it was an incredibly compelling theory.

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

The Captain’s Theory

Captain Pruss, who had been in charge of the ship for its entire run, also believed that sabotage had taken down the Hindenburg—and he, along with others in the know, pointed at one suspect.

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

MiddKid Productions, Timeless (2016-2018)

The Acrobat

One would think that if your mission was to board a ship and sabotage it, you’d lay low—but that wasn’t the case with passenger Joseph Späh, a German acrobat who sometimes went by the name Ben Dova, and who escaped by jumping from the burning craft. Späh had brought a dog on the trip, who was treated as cargo and thus stayed in a freight room throughout the journey.

As such, Späh was allowed to make unchaperoned trips into crew-only areas of the ship to care for the dog.

Jonathan Cardy, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Jonathan Cardy, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Differences Of Opinion

One through line in the theories regarding suspects of sabotage is that they, despite Eckener’s anti-Nazi sentiments, were trying to take down the ship in the name of anti-Nazi parties. And then one opposing theory speculates that Hitler himself arranged for the ship to burn due to Eckener’s opinions.

Ultimately, investigations done by parties on both sides of the crash—Germany and the US—found no evidence that sabotage was the culprit.

Static Discharge

As Eckener was briefed, and learned that it was fire and not a single explosion that had consumed the aircraft, he changed his position to support a theory that a static discharge had been responsible for the disaster. He believed that it was possible a static spark had ignited hydrogen on the outer skin of the ship.

An Unscientific Explanation Of A Scientific Phenomenon

When wet ropes sent down for mooring created a difference in potential between the duralumin outer layer, which was grounded, and the ramie skin within, a spark could’ve occurred—with any hydrogen residue becoming an accelerant.

New Evidence Emerges

In 2021, as part of the PBS program Nova, Konstantinos Giapis of Caltech performed an experiment designed to test whether the static spark theory could be replicated—and the results were, quite literally, explosive. In his experiment replicating the conditions, Giapis was able to cause a spark between the skin and frame.

San Diego Air and Space Museum, Picryl

San Diego Air and Space Museum, Picryl

Can’t Start A Fire Without A Spark

Essentially, according to Giapis, the ship became a capacitor, causing not just one, but a number of sparks—one of which ultimately happened near a hydrogen leak, which ignited and caused the disaster. Giapis’s theory and evidence have become one of the most compelling explanations for the true cause of the Hindenburg disaster, nearly 100 years after that fateful day.

San Diego Air and Space Museum, Picryl

San Diego Air and Space Museum, Picryl

The Camera Doesn’t Lie

The sight of a previous airship disaster had spurred the German public to rally around the ship’s maker and demand advancements in airship technology. The presence of film footage and audio reports from the Hindenburg disaster had the opposite effect on the public. Though there had been worse disasters, they had mostly occurred on board military airships. The Hindenburg disaster shredded the public’s confidence in the form and essentially ended the era of the giant passenger-carrying airship.

When Bigger Isn’t Better

“When arranging a tour around the United States, I had decided to cross on the Titanic. It was rather a novelty to be on the largest ship yet launched”—Lawrence Beesley, Titanic survivor.

Examining the similarities between the sinking of the Titanic and the Hindenburg disaster, it’s impossible not to make connections between the two. There’s the visual of the stern going down before the bow in both. There were signs in both cases that the ships in question were vulnerable, and multiple opportunities to have course-corrected in both.

And then, of course, the most overwhelming similarity: The loss of two literal titans, largest in their respective fields, proving that there is no safety in size, and little benefit to hubris. When the march of progress moves too fast, there will inevitably be those caught under the heel of its heavy boot.