Who Are The Ho-Chunk People Of Wisconsin?

The Ho-Chunk are one of the two First Nations of Wisconsin, and were once the dominating tribe in their territory. But after the arrival of Europeans, their tribe nearly went extinct.

As skilled warriors who regularly held war rituals, and appealed to spirits for protection—their enemies admittedly felt fear. The Ho-Chunk were targeted by many, from rival tribes to colonists and hate groups, and spent centuries fighting for their land and their culture.

But even after decades of forceful removals, the Ho-Chunk got good at saying no—and the American government met their match.

From their traditional lifestyle to their fight for their land, this is the incredible story of the Native American Ho-Chunk tribe.

What Language Do They Speak?

Th Ho-Chunk speak a Siouan language, which they believe was given to them by their creator, Mą’ųna ("Earthmaker").

Their native name is Ho-Chunk, which translates to “sacred voice,” or “People of the Big Voice,” and means “mother tongue”—as in they originated the Siouan language family.

But their native name isn’t what many Americans know them by.

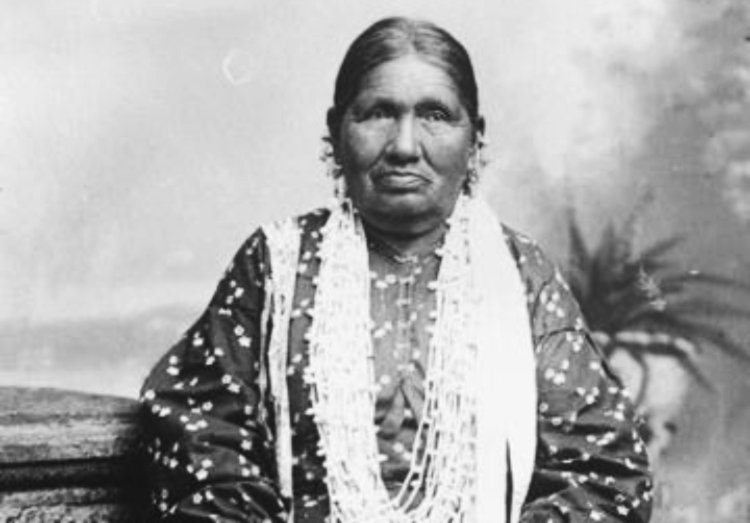

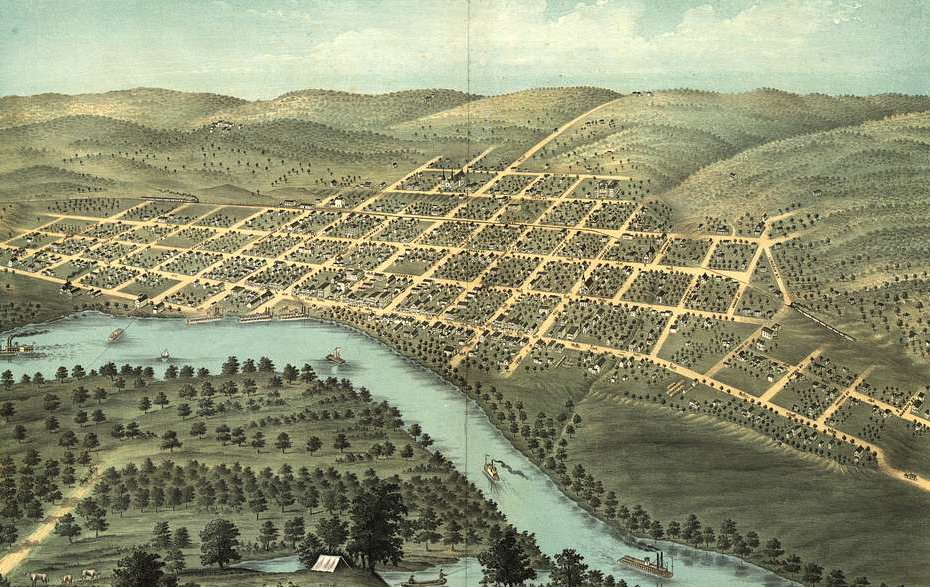

Omaha Public Library, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Omaha Public Library, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

What Other Names Do They Go By?

The Ho-Chunk are also known as Hocąk, or Hoocągra. But long ago, neighboring tribes gave them the name Ouinepegi, which government agents later heard as Winnebago. This was then their official name until 1993, when the Ho-Chunk took back their native name.

And their name wasn’t the only thing they took back.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Where Do They Live?

Today, the Ho-Chunk people are enrolled in two federally recognized tribes, the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin and the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska. The land parcels in Wisconsin are actually lands they once owned, but had to buy back.

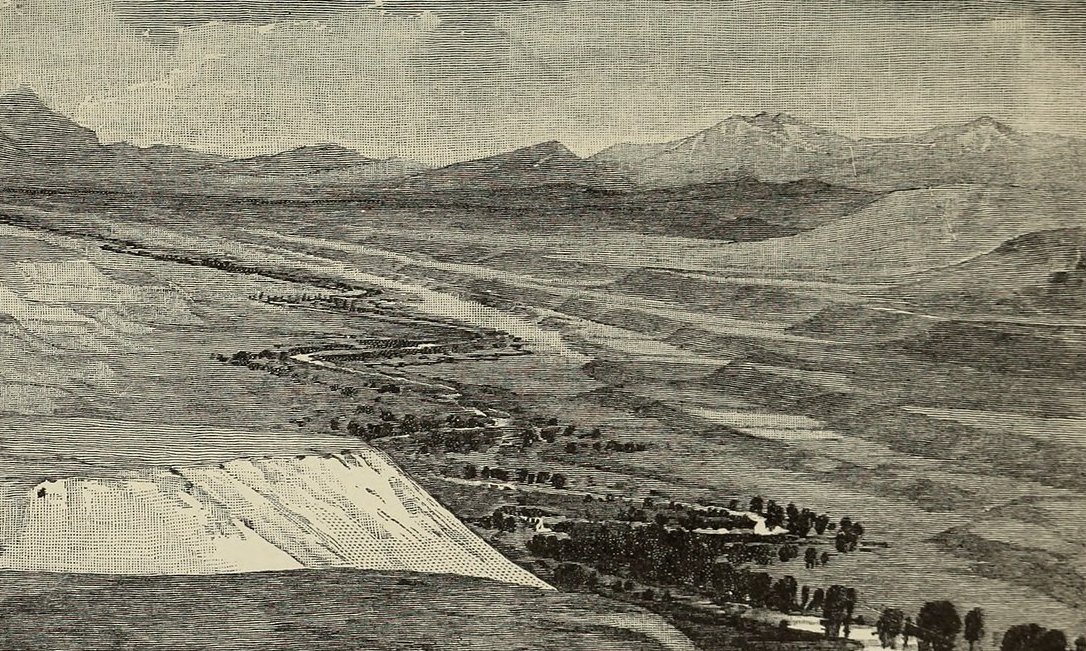

Historically, their territory included parts of Wisconsin, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and Missouri. However, after wars with neighboring tribes, and later the United States, the Ho-Chunk were brutally forced off their lands, and were moved around by government officials who couldn’t decide where to put them.

Oral history suggests some of the tribe may have been forcibly relocated up to 13 times by the federal government—and their population suffered as a result.

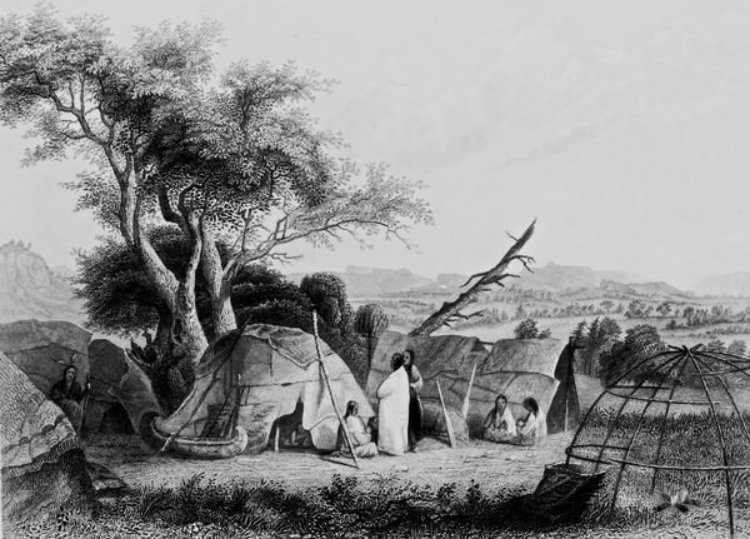

Seth Eastman, Wikimedia Commons

Seth Eastman, Wikimedia Commons

How Big Is Their Tribe?

Today, between their two federally recognized tribes, the Ho-Chunk population is believed to be around 12,000—which is actually still far less than before.

The Ho-Chunk were the dominant tribe in their territory in the 16th century, with a population estimated at over 20,000. However, over time, they saw significant changes in population, with their lowest numbering a mere 500 individuals back in the 17th century.

The severe population loss was believed to be due to weather, disease, war, and competition for resources from migrating Algonquin tribes.

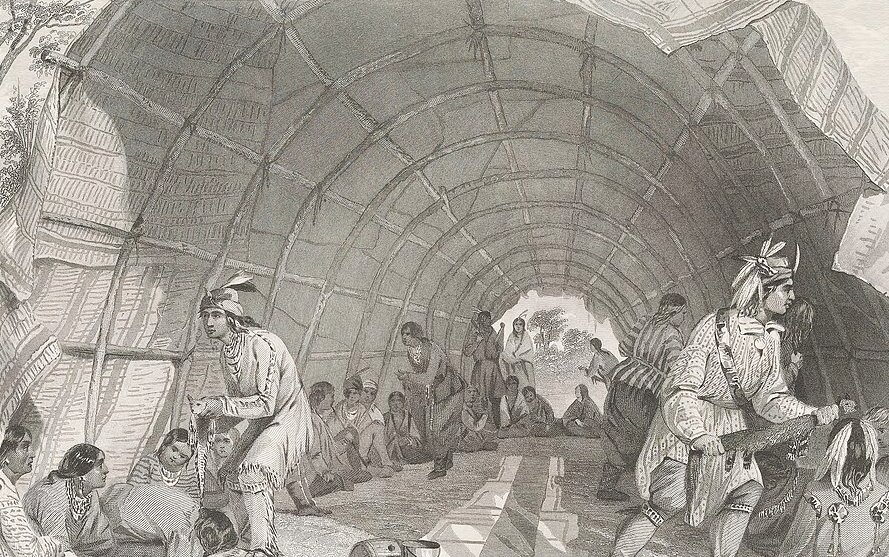

Schoolcraft et al, Wikimedia Commons

Schoolcraft et al, Wikimedia Commons

What Was Their Traditional Lifestyle Like?

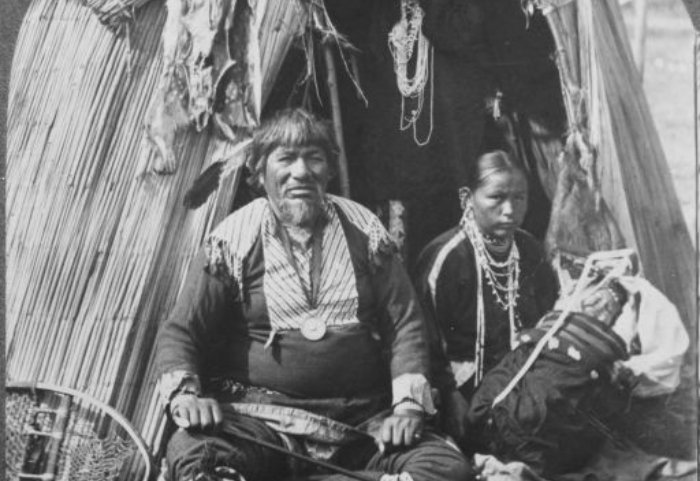

Traditionally, the Ho-Chunk were known to hunt, farm, and gather food from local sources, including nuts, berries, roots, sap, and edible leaves. They were one with their environment, making the best use of their resources.

And while they were known to live in larger, more permanent villages, some Ho-Chunk moved with the seasons, from area to area to find food. In the summer, many families would return to Black River Falls in Wisconsin for the abundance of fresh berries—beautiful brambles that would later be tragically trapped behind fencing.

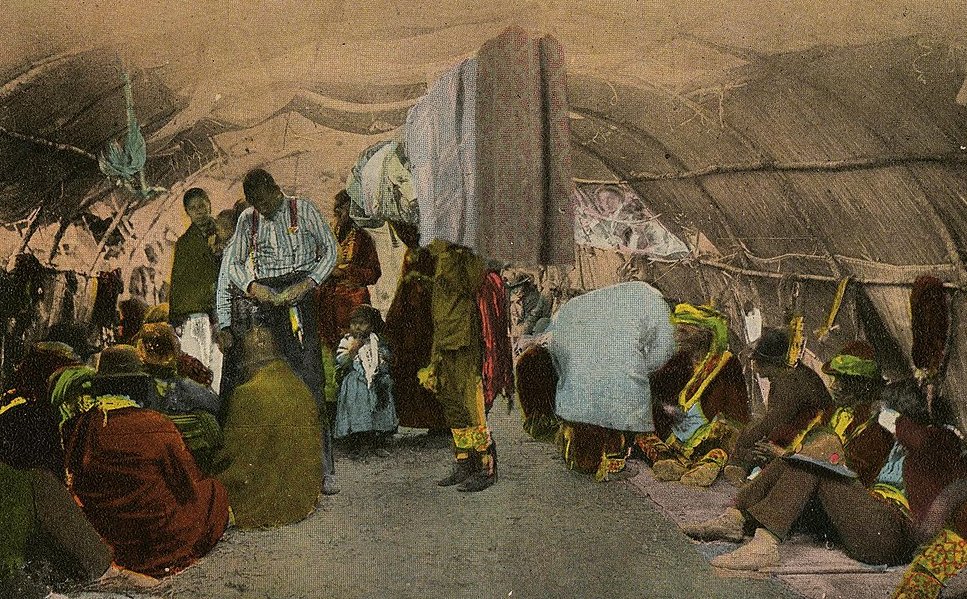

What Were Their Villages Like?

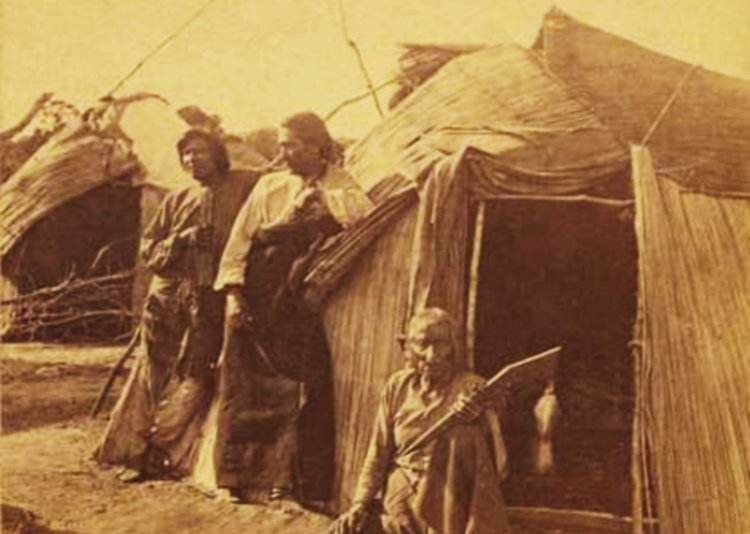

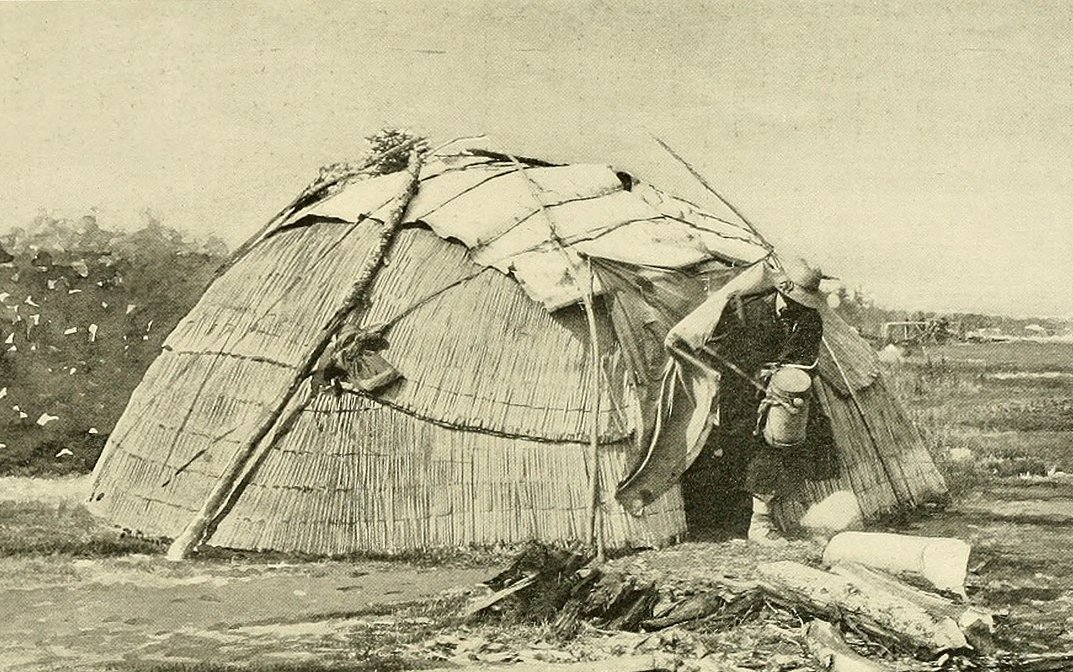

The Ho-Chunk lived in semi-permanent villages, typically in areas with a variety of resources nearby. Their homes were dome-shaped wickiups (or wigwams), called ciiporoke. They were built with a wooden frame covered with sheets of bark or woven plant materials.

Building their homes was often a joint effort between family members of both genders—but they did have gender-specific roles within the family as well.

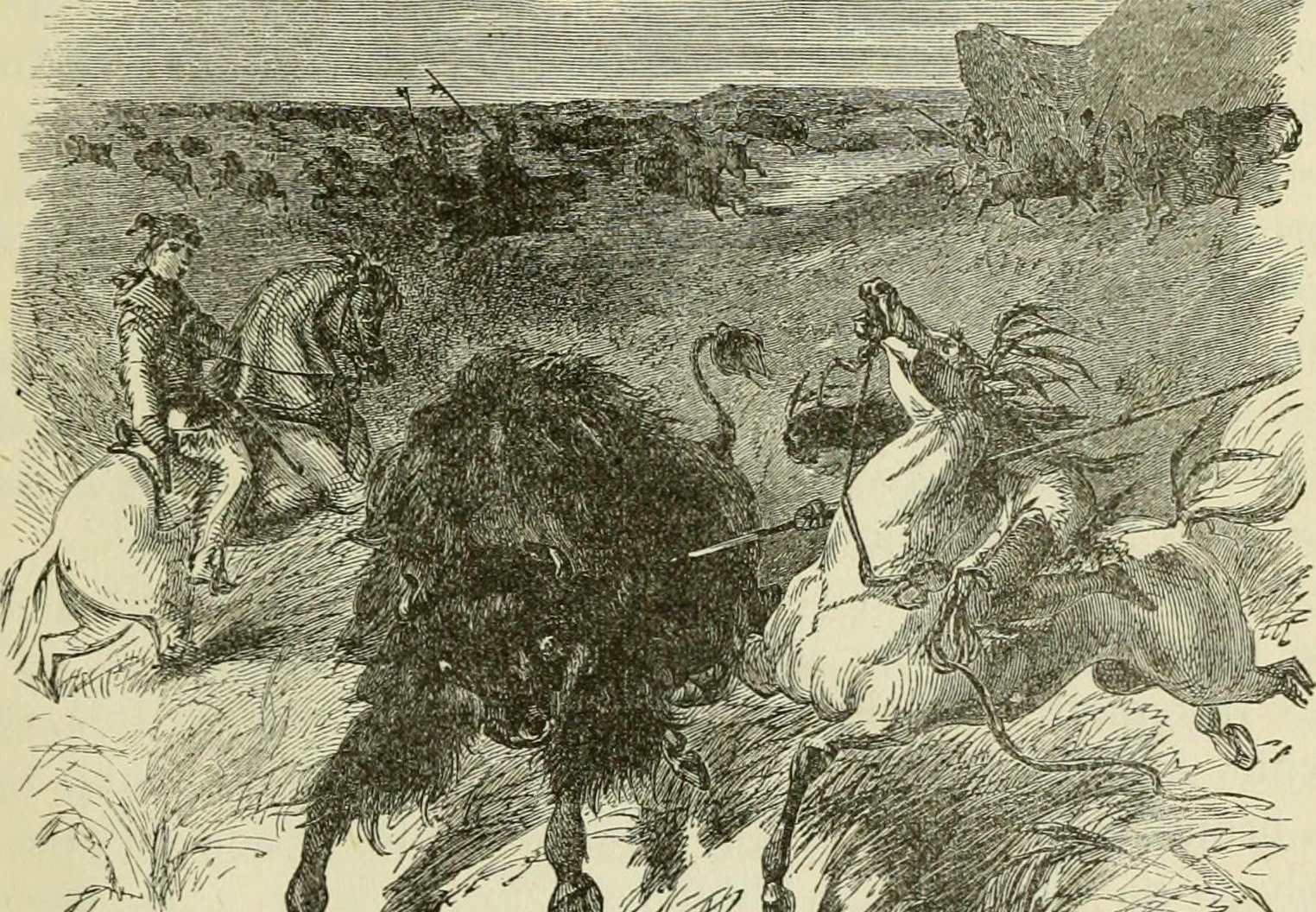

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

What Were Ho-Chunk Women Responsible For?

Ho-Chunk women were responsible for growing, gathering, and processing food for their families. They cultivated corn and squash, and processed cooked game, making dried meats to sustain their families during travel. Sugar from maple trees was used to make a variety of maple syrup candies.

Aside from their work in the kitchen, the Ho-Chunk women were ultimately responsible for the survival of their families. They cared for the children and the elders, they made clothing and storage bags from tanned hides and local resources, and they also used roots and leaves to make medicines and remedies.

Henry Hamilton Bennett, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Hamilton Bennett, Wikimedia Commons

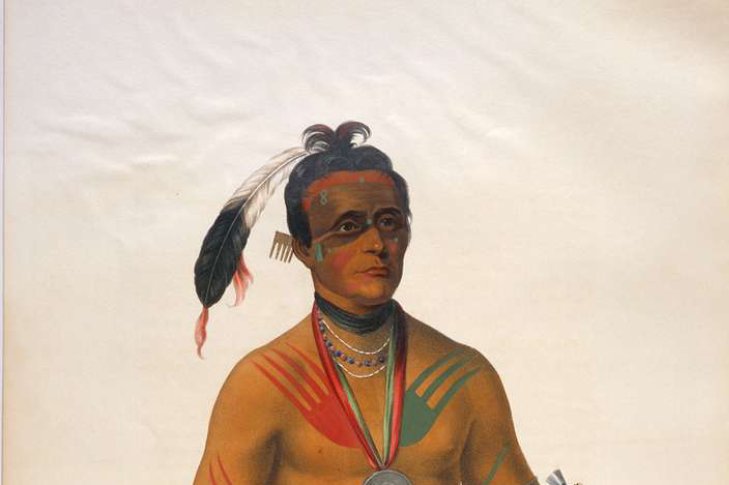

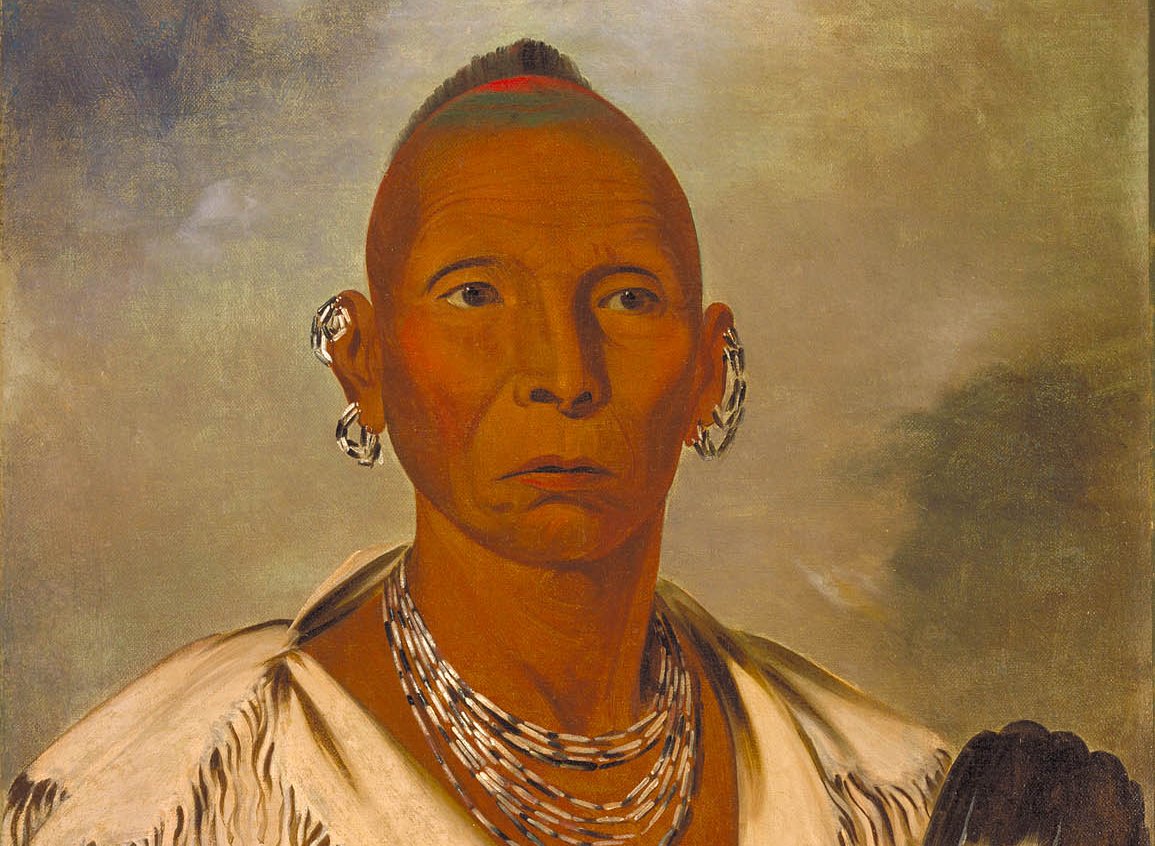

What Were The Ho-Chunk Men Responsible For?

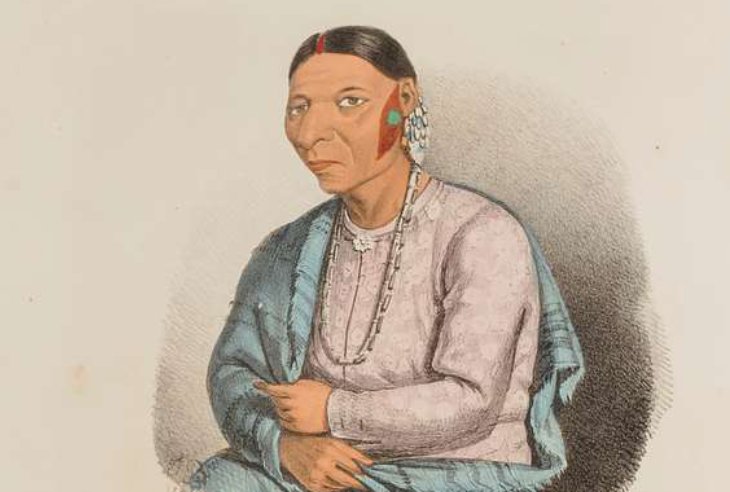

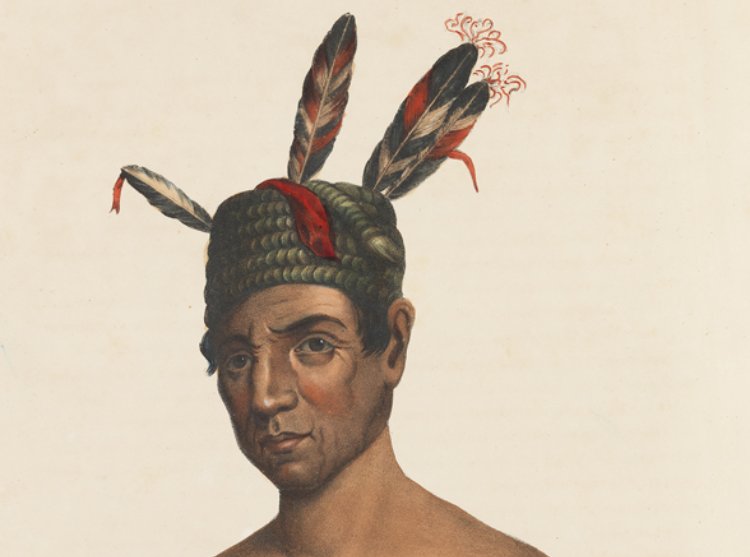

Traditionally, the main role of the Ho-Chunk man was as a hunter—and a warrior when needed. As skilled fishermen, they speared fish and clubbed them to death. They mainly hunted and trapped muskrat, mink, otter, beaver, and deer. In later years, the Ho-Chunk began hunting buffalo. They’d use handmade dugout canoes to travel upriver to the prairies to follow the herds.

Some men also learned to create jewelry and other body decorations out of silver and copper, for both men and women.

But, before a Ho-Chunk could become a man, boys would have to go through an important rite of passage first.

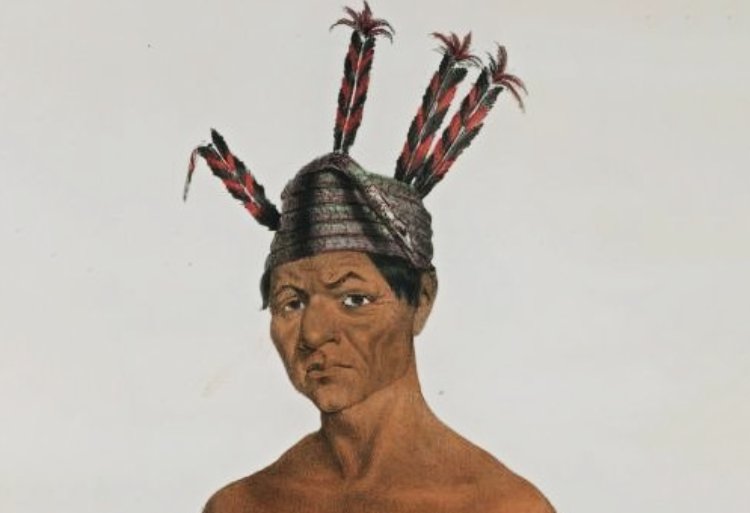

James Otto Lewis (1799-1858), Wikimedia Commons

James Otto Lewis (1799-1858), Wikimedia Commons

The Puberty Ritual

Before boys could be considered men, they would have to go through a rite of passage at puberty. This involved the boy going into the forest for several days where they would fast all day and dream all night. Their dreams were expected to bring them a guardian spirit—without it, their lives would be miserable. Many boys would fast for as long as they could until they received the spirit—even if it brought them to near-starvation.

The Puberty Ritual For Girls

When a girl began menstruation, she would be required to stay in a dwelling built by her mother that was farther away from the village. Fasting was also a part of this ritual, however not in entirety. Menstruating girls were allowed small bits of food to keep them nourished, but fasting was important for achieving visions. If she had a vision, it was considered a special blessing—and usually indicated she would be blessed with a good husband and healthy children.

Wisconsin Historical Society, Getty Images

Wisconsin Historical Society, Getty Images

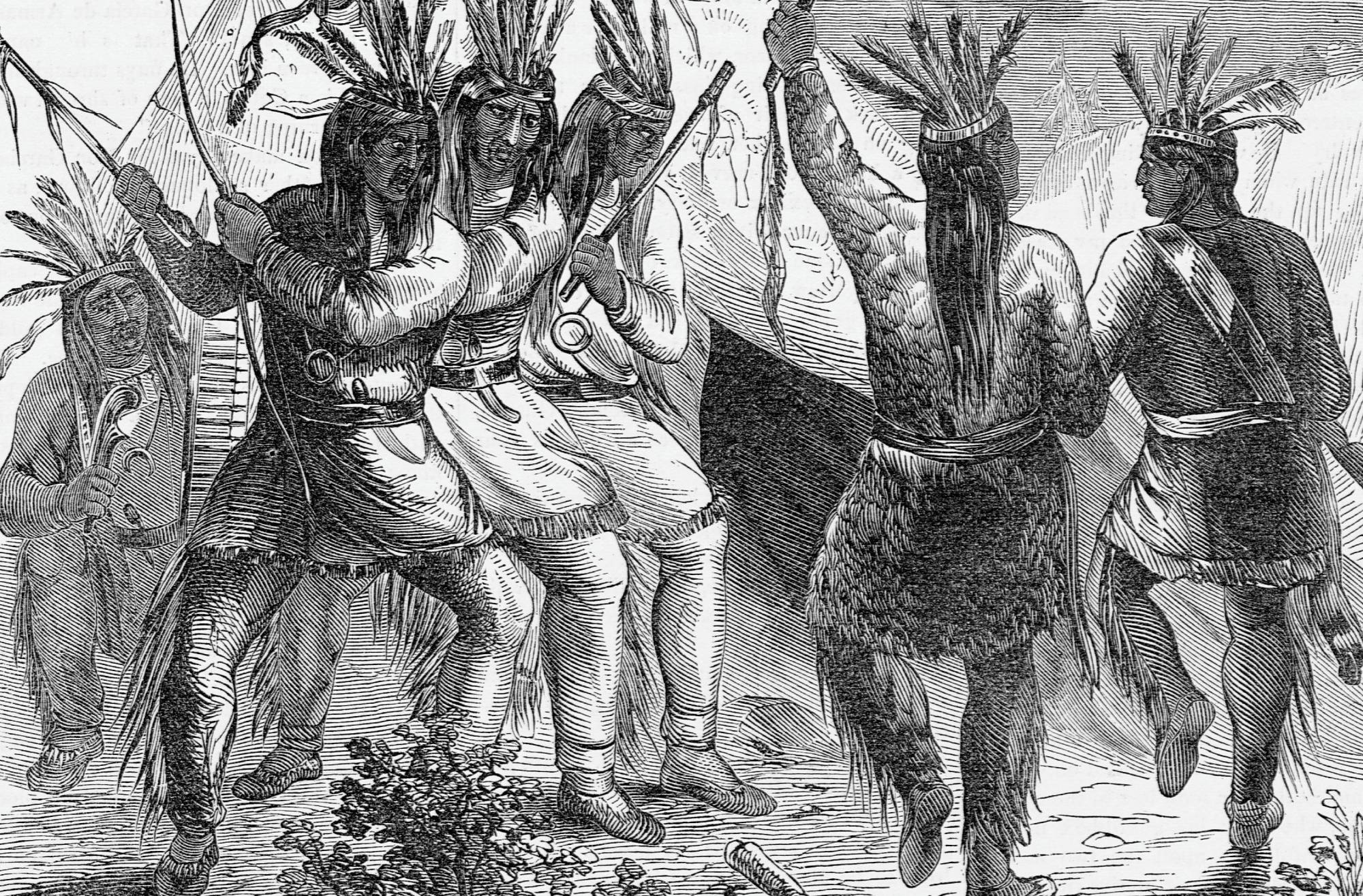

The War Bundle Feast

Besides having a guardian spirit, men would also try to acquire protection and powers from other specific spirits, which was done by making offerings. The chosen offerings would be added to a large fire, along with tobacco, and the smoke would bring the offerings to their spirits.

For example, men would not go into a battle without first performing the "war-bundle feast". This ritual honored both the Night Spirit and the Thunderbird spirit. The men would have a large feast and offer pieces of meat and tobacco to the Earthmaker.

The blessings these spirits gave the men were embodied in objects that together made the war-bundle. These objects could include feathers, bones, skins, flutes, and paints.

What Religion Did The Ho-Chunk Practice?

The Ho-Chunk religion was mainly spiritual. The central figure was Mą’ųna—which means "Earthmaker", and the Sun was also an important figure, especially when appealed to for war pursuits.

Female deities included the Earth and the Moon. And animals were also represented by grand supernatural forces—which were those seen during vision quests.

Other figures helped Earthmaker, and could take human and animal form to help the humans: Trickster, Hare, the Twins of Flesh and Spirit, Red Horn, and Turtle.

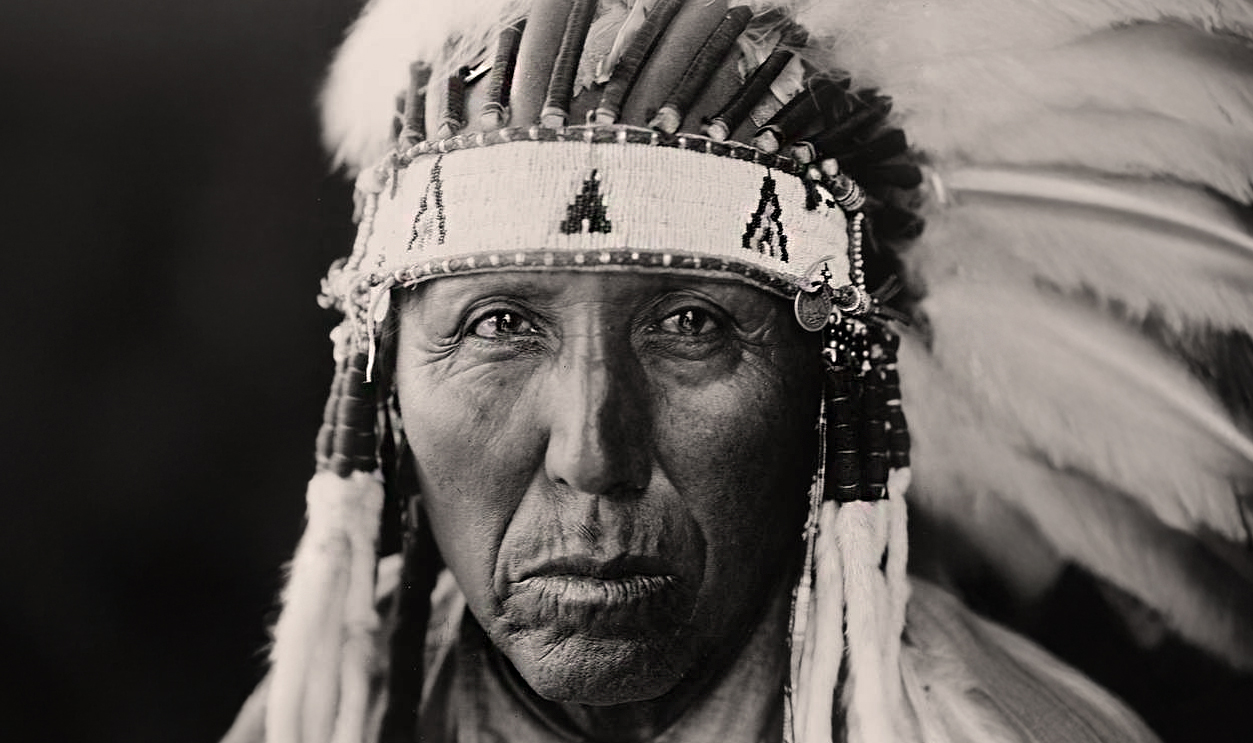

Frank Rinehart, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Frank Rinehart, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Good And Bad Spirits

It was common for battles between good spirits and bad spirits to occur. Rituals were often held for the spirits the Ho-Chunks felt linked to, such as the Night Spirit, which was appealed to for success in war. Vision quests were common when calling upon protective spirits.

They had to be mindful, too. Taboos or incorrect behavior would often upset the spirits, and lead to devastating consequences.

British Museum, Wikimedia Commons

British Museum, Wikimedia Commons

What Is Taboo In The Ho-Chunk Culture?

Transgressions of taboos were said to lead to illness, and often death. In many of the Great Lakes tribes, taboos during pregnancy were strict. Both parents, but especially the mother, were warned not to look at deformed animals or people, as it was believed it could harm the child. Also, eating or looking at turtles or rabbits was said to cause the baby to develop the “jerky” motion of a turtle, or the “fits” associated with rabbits.

If a pregnant woman happened to see one of these taboo animals, she would save a bit of the hair or flesh to add to the baby’s bath water after birth. This would then reverse any potential harm that might have occurred during the pregnancy.

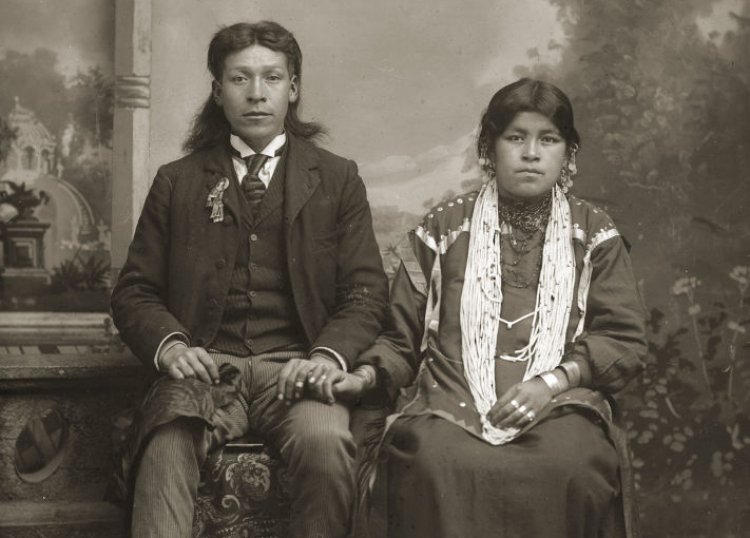

What Was Marriage Like For The Ho-Chunk People?

Traditionally, Ho-Chunk marriage was fairly simple. Once the man and woman had gone through their individual rites of passage, they could begin to court their love interest. However, their partner had to be from a different clan.

Men would provide offerings to the woman’s family, and the families would exchange gifts. Instead of a wedding ceremony, the couple would simply go off on their own for a few days. When they returned, they were considered married.

Wisconsin Historical Society, Getty Images

Wisconsin Historical Society, Getty Images

How Many People Could They Marry?

Most traditional Ho-Chunk marriages were monogamous, but polygyny was allowed for important men, who could have two or sometimes three wives—and they were usually sisters, as it was said to make it easier for the women to get along.

If a marriage wasn’t successful, the woman would simply go back to her father’s lodge, and in most cases, marry someone else. Bachelorhood or spinsterhood was mostly unheard of. In fact, some Ho-Chunk married several times.

Wisconsin Historical Society, Getty Images

Wisconsin Historical Society, Getty Images

How Was Their Clan System Set Up?

Before the US government removed the Ho-Chunk from their native land, the tribe consisted of 12 clans. They were further organized into two phratries: the Upper (Air) division, which contained four clans, and the Lower (Earth) division, which contained eight clans.

The clans were associated with animal spirits and represented traditional responsibilities. Each clan had a role in the survival of the people. The Thunderbird clan, for example, was the clan from which chiefs were appointed, and the Bear clan was responsible for enforcing discipline within the community, and overseeing prisoners.

University of Cincinnati Libraries Digital Collections, Picryl

University of Cincinnati Libraries Digital Collections, Picryl

When Did The Ho-Chunk First Go To War?

Oral history says the Ho-Chunk have always lived in their current homelands of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, and Illinois—but not always freely. Even before the arrival of Europeans, the Ho-Chunk were often at odds with neighboring tribes—usually due to competition for resources, and assumed boundaries.

But these intertribal wars escalated once the colonists arrived, and tribes began taking sides.

European Contact

European contact came in 1634 with the arrival of French explorer Jean Nicolet—the first European to set foot in what is now the US state of Wisconsin. He had come from French-occupied Canada, and was tasked with negotiating treaties and initiating fur trading with the native tribes of the area.

Upon Nicolet’s arrival, he was greeted by a large grouping of Ho-Chunk—estimated to be about 5,000 warriors. But their interaction was not what you might expect.

Skiba, Justin M., CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Skiba, Justin M., CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

What Happened When The Ho-Chunk Met The Europeans?

The Ho-Chunk naturally proceeded with caution, however they were likely intrigued by the newcomers, as they looked drastically different than other tribes they had known. But even with an obvious language barrier, the two groups managed to keep their interaction peaceful—and even began a trade relationship.

Nicolet and his fellow French traders described the Ho-Chunk as “powerful and skilled warriors who frequently made war with other tribes". Although Nicolet was aware of the intertribal wars going on, he continued to foster a mutually advantageous relationship with the Ho-Chunk.

Sulte, Benjamin, Wikimedia Commons

Sulte, Benjamin, Wikimedia Commons

What Did They Trade?

Shortly after forming a friendly relationship with the French, the Ho-Chunk opened up to a newer way of life. The French had shown them metal tools, and taught them how to use an ax to chop down trees. They also introduced the Ho-Chunk to something that ended up being a major game-changer: guns.

As soon as the Ho-Chunk realized just how valuable guns were, they offered up their best trade item—fur. They began regularly trading fur and tobacco for things like axes, blades, and guns.

But what the Ho-Chunk didn’t expect was that they were gaining a lot more than just physical items when they traded with the newcomers—and not everything given was good.

What Else Did Trading Bring?

Within a few years after the arrival of the Europeans, the Ho-Chunk, as well as other native tribes of the area, began to experience a whole world of problems. At this time, numerous Algonquian tribes were migrating west to escape the aggressive Iroquois tribes in the Beaver Wars—which created a serious problem when it came to resources.

And although the Ho-Chunk had a decent group of warriors (along with their newfound weapon of choice), they simply were not large enough, and had to yield to the Algonquian tribes’ greater numbers. They began moving south.

But that wasn’t the most devastating part.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

The Introduction Of Disease

The fur trade brought in large groups of people—including both native tribes and French colonists. And with that, came disease. The Ho-Chunk had always lived off the land, using only what they knew to be safe. However, with the sharing of tools, came the sharing of germs, and it didn’t take long for new diseases to wipe them out.

Between the intertribal wars and disease, the Ho-Chunk population went from tens of thousands down to a mere 500.

Not only that, a significant number of Ho-Chunk warriors were lost in a horrific tragedy.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Winter Storm Tragedy

While sources disagree on the details, oral history maintains that about 500-600 Ho-Chunk warriors were lost at sea during a major storm during a campaign against an enemy tribe.

With the onslaught of disease, and the huge loss of warriors, the tribe’s population was severely suffering. But historians believe the Ho-Chunk may have gone looking for trouble at one point, too.

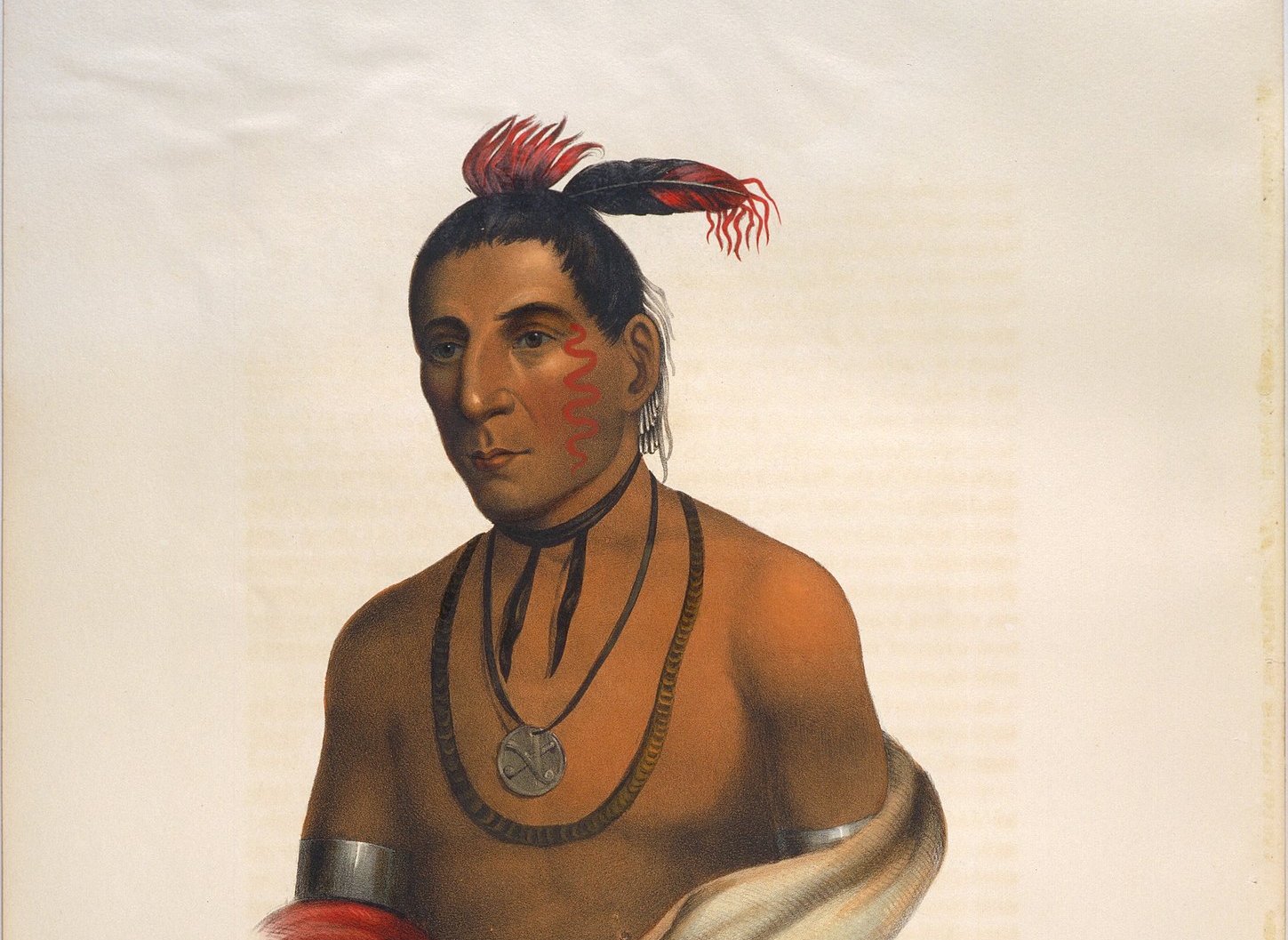

Thomas Loraine McKenney & James Hall Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Loraine McKenney & James Hall Wikimedia Commons

Who Did The Ho-Chunk Take Their Frustrations Out On?

According to historian R David Edmunds, many of the Ho-Chunk’s enemies had actually helped them during their time of suffering and famine—including their main enemy, the Illinois Confederacy. But then, aggravated by the loss of their hunters, the Ho-Chunk attacked the Illinois Confederacy—which prompted an immediate retaliation.

As we know, the Ho-Chunk were no match for the Illinois Confederacy, and nearly all of them were killed as a result. Anyone left fled the area.

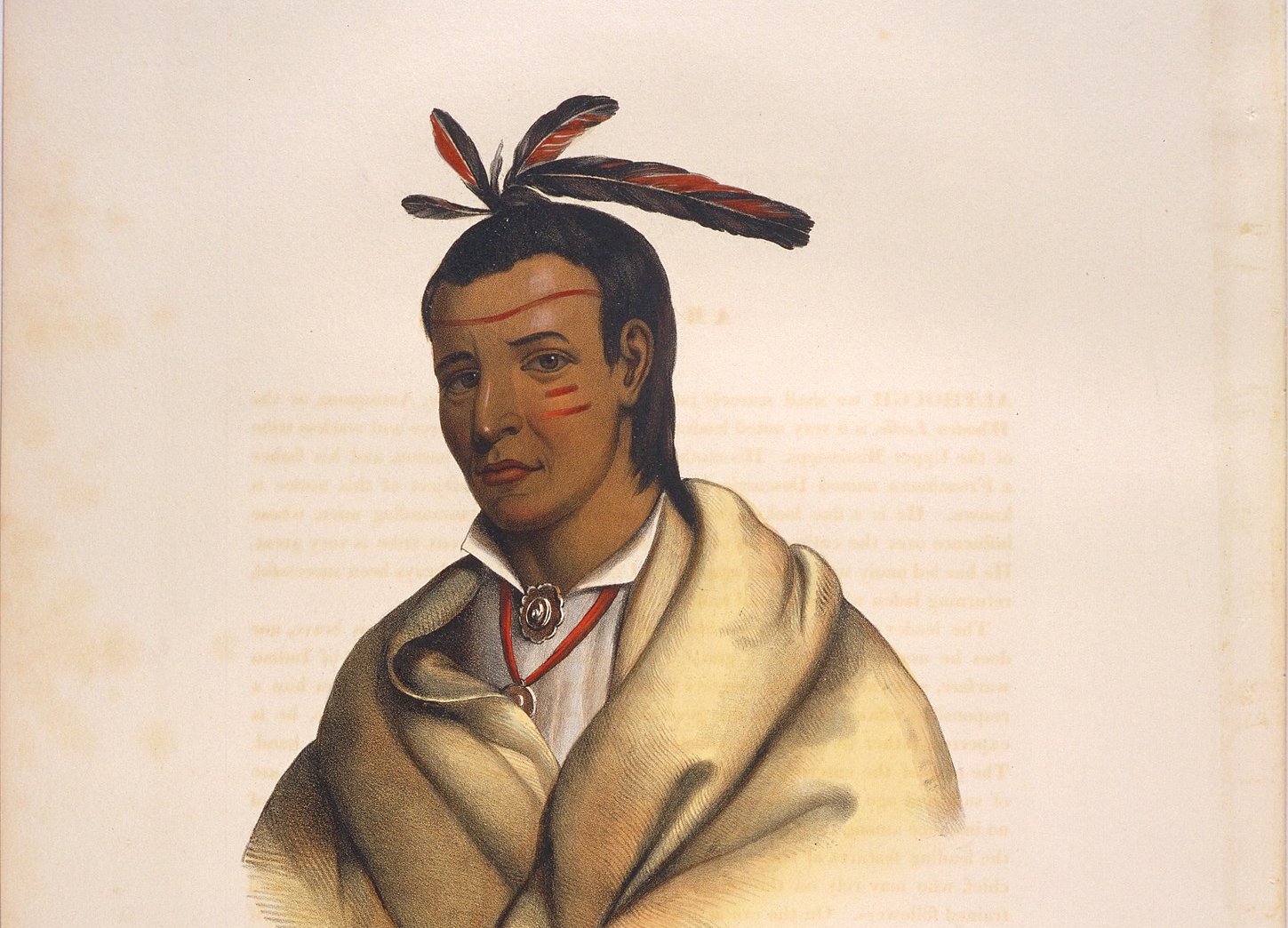

Thomas Loraine McKenney & James Hall, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Loraine McKenney & James Hall, Wikimedia Commons

How Did They Recover Their Population?

Years later, peace was established between the French and the Iroquois, and many Algonquian peoples returned to their homelands to the east, including the Ho-Chunk. Their population had dipped lower than 500, but had now started to increase as the Ho-Chunk began intermarrying with neighboring tribes in an effort to boost their numbers. Some Ho-Chunk even married French fur traders and trappers. By 1736, their population was estimated to be closer to 700.

During this time, their traditional customs changed as they mixed with other tribes. But once again, the heavily-populated areas only brought on more disaster.

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

The Smallpox Epidemic

During the infamous smallpox epidemic of 1757, the Ho-Chunk suffered another immense loss to their population. And then again, later in 1836, a second smallpox epidemic broke out, taking the lives of nearly a quarter of their population. By 1848, their numbers were estimated at 2,500.

Their population was up and down for many years, but disease wasn’t their only threat.

The Winnebago War

The peace between the French and the Iroquois was much appreciated, but it wasn’t the only war going on at the time.

The Winnebago War, also known as the Winnebago Uprising, was a brief conflict that took place in 1827, primarily in Wisconsin. The Ho-Chunk were reacting to a wave of lead miners trespassing on their lands—along with a circulating rumor that had them suddenly seeing red.

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

What Caused The Winnebago War?

Following the war of 1812, the United States pursued a policy of trying to prevent wars among Native Americans in the Upper Mississippi River region—though it was not exactly for humanitarian reasons. Intertribal warfare made it more difficult for the US to carry out their Indigenous removal processes.

In 1825, a multi-tribal treaty (which included the Ho-Chunk) was finalized, defining the region’s tribal boundaries. However, large numbers of American miners were trespassing anyway—horrifically mistreating the Ho-Chunk while they were at it.

King, F. H. (Franklin Hiram), Wikimedia Commons

King, F. H. (Franklin Hiram), Wikimedia Commons

The Methode Family Murder

In March of 1826, a French-Canadian man named Methode, his Native American wife, and their children were gathering maple syrup in present-day Iowa, when they were apparently slain by a Ho-Chunk raiding party that had been passing through. The victims were targets of opportunity, as the Ho-Chunks had no reason to attack the unsuspecting family.

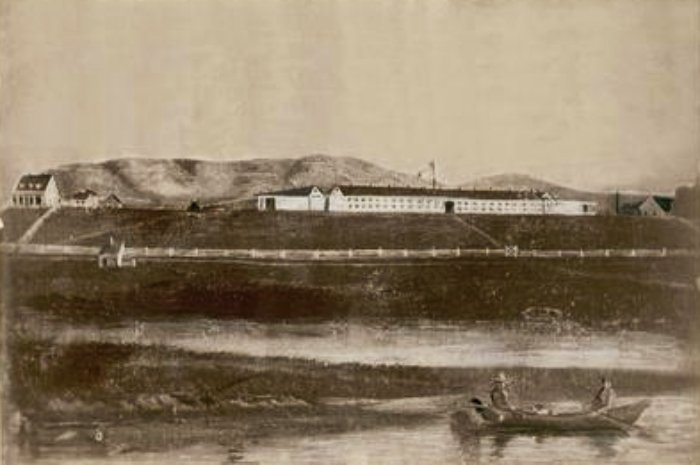

As a result, two Ho-Chunk suspects were apprehended by Prairie du Chien militiamen and taken to Fort Crawford. But they weren’t there for long.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

What Happened To The Ho-Chunk Prisoners?

The two Ho-Chunk suspects escaped Fort Crawford. But instead of going after them, US Army Lieutenant Colonel Willoughby Morgan went ahead and took two other Ho-Chunk people as hostages, and demanded that the Ho-Chunk tribe turn over the men responsible for the deaths of the Methode family.

And while the Ho-Chunk felt their act of violence was justified, they made a difficult choice.

Benjamin F. Gue, Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin F. Gue, Wikimedia Commons

How Did The Ho-Chunk Appease The US Army?

On July 4, 1826, the Ho-Chunk delivered six men to Morgan at Fort Crawford. None of these men had anything to do with the slaying, but were surrendered to “appease American anger” and deflect punishment away from the tribe as a whole.

But this wasn’t good enough for Morgan. He wanted the men responsible. He still kept all six men, though. And then he reinforced the fort after a rumored threat that the Ho-Chunk were planning an attempt to flee the prisoners.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

What Happened To The Men Responsible For The Slaying?

Eventually, two Ho-Chunks were turned over to the Americans and indicted for the slaying. But that wasn’t the end of the drama. American Colonel Josiah Snelling then moved the garrison to Fort Snelling, where he hoped to reduce hostilities between the Dakotas and the Ojibwes—and he took the two Ho-Chunk prisoners with him.

But a few months later, the Dakotas attacked an Ojibwe party near Fort Snelling. Colonel Snelling got involved and took four of the Dakotas and turned them over to the Ojibwes, who then killed them.

This infuriated the Dakotas, who then turned to the Ho-Chunks for help—but they didn’t just ask nicely.

What Did The Dakotas Tell The Ho-Chunks?

The Dakotas needed the Ho-Chunk’s help to take down the Americans, so they falsely told them that the Ho-Chunk prisoners had also been turned over to the Ojibwe for execution. This was the rumor that had the Ho-Chunk seeing red.

The rumor was already enough to convince the Ho-Chunk to take action against the United States—but then it got worse.

How Did Things Escalate?

Another rumor surfaced, claiming that several Ho-Chunk women were horrifically mistreated by an American riverboat crew along the Mississippi River. And although it had not technically been confirmed, it was enough to cause the Ho-Chunk to break off diplomatic relations with the US. They didn’t show up for the next scheduled treaty conference—instead, they prepared for war.

New York Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

New York Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

How Did They Get Revenge?

In late June 1827, the Ho-Chunk took things to the next level and delivered an awful attack on an unsuspecting target. Ho-Chunk leader Red Bird and two of his men, Wekau and Chickhonsic, went to Prairie du Chien to seek revenge for what they believed were the executions of the Ho-Chunk prisoners, and the mistreatment of their women.

But when they couldn’t locate their intended victim, they went ahead and targeted the cabin of Registre Gagnier, the son of an esteemed African American nurse and midwife named Aunt Mary Ann—and it was absolutely ruthless.

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

What Happened To The Gagnier Family?

The Ho-Chunk warriors were sly in their approach. Gagnier welcomed the three Ho-Chunk men into his home and offered them a hot meal. But what happened inside was absolutely horrific. According to oral history, Red Bird shot and killed Gagnier, while Chickhonsic shot and killed a friend of the family who was also there.

Wekau tried to shoot Gagnier’s wife, but she wrestled the gun away before escaping with her young son. Instead, he stabbed and scalped Gagnier’s infant daughter—who somehow managed to survive the brutal attack.

The Ho-Chunk men then returned to their village with the three scalps, and a celebration was held in their honor.

As horrific as this was, it was not the end.

SMU Central University Libraries, Wikimedia Commons

SMU Central University Libraries, Wikimedia Commons

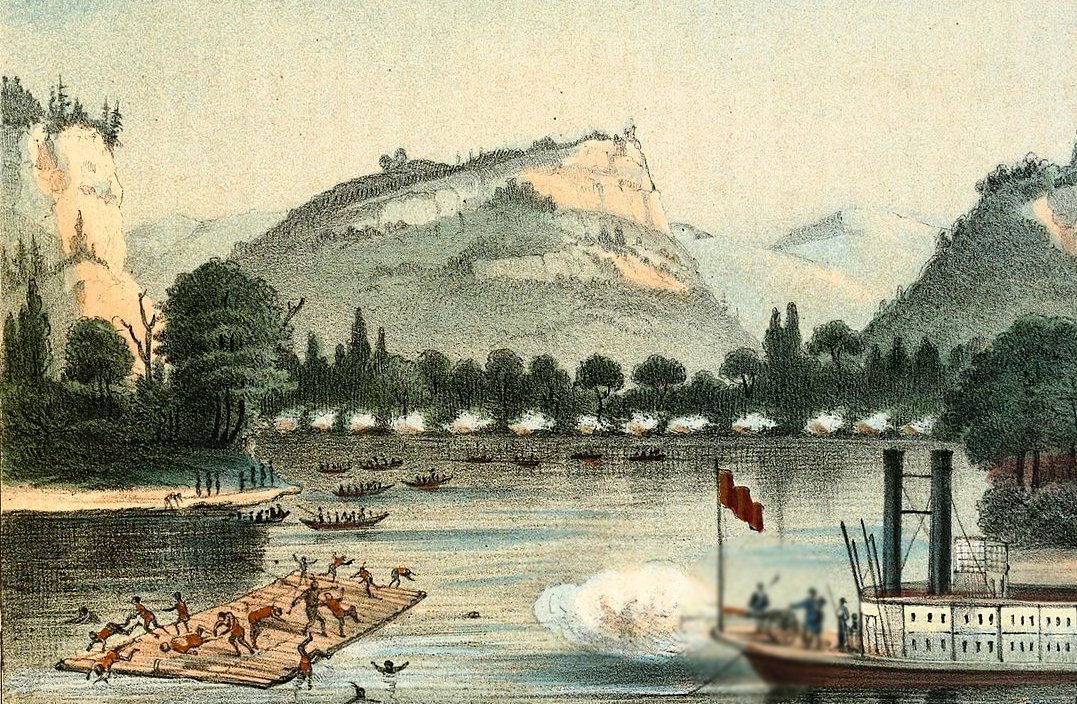

Who Was Their Next Target?

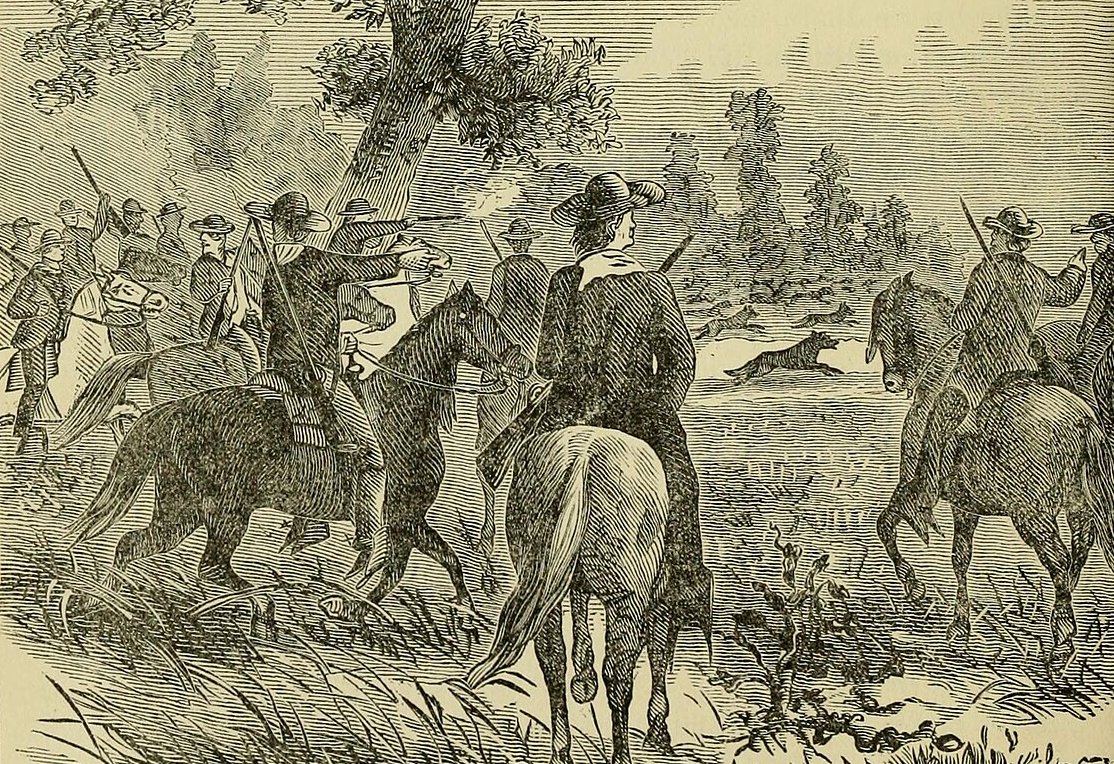

On June 30, 1827, the same group of Ho-Chunks struck again. About 150 Ho-Chunks, with a few Dakota allies, attacked two American keelboats on the Mississippi. Two Americans were killed and four were wounded. Seven Ho-Chunk also died in the attack.

While this attack was relatively small in comparison to others, according to historian Patrick Jung, it “was significant because it was the first act of war committed against the United States by Indians in the region since the War of 1812".

Iconographic Collection, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Iconographic Collection, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Who Supported The Ho-Chunk?

After that, the Ho-Chunk attempted to get other neighboring tribes to join the fight, but many of them remained neutral. Some Potawatomis participated by killing some American livestock, but Potawatomi leaders urged their people to stay out of the war.

In fact, many other Ho-Chunks decided to follow suit, and distanced themselves from the actions of Red Bird and the Prairie La Crosse Ho-Chunks, who were responsible for it all.

Without allies, the Ho-Chunk were doomed. By mid-July, the “Red Bird Uprising” was over. But it still wasn’t the end of the war for the Ho-Chunk.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Picryl

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Picryl

The Black Hawk War

A few years later, in 1832, the Black Hawk War began between the US and Native Americans, led by Black Hawk, a Sauk leader. At the time, the US had been trying to enforce a purchase agreement that Black Hawk had believed to be invalid.

The Ho-Chunk participated briefly in this war, carrying out minor attacks. However, it was largely fought on Ho-Chunk land. In the end, the Sauk people signed a treaty with the US government. In exchange for $660 million, the Sauk gave up 6 million acres of land—some of which may have belonged to the Ho-Chunk.

After that, things got progressively worse for the Ho-Chunk.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

Series Of Forced Removals

Once that treaty was signed, more followed. Land cessions plagued the 19th century. In fact, an entire series of relocations occurred. The Ho-Chunk tribe was relocated to reservations in Wisconsin, Minnesota, South Dakota, and finally Nebraska. Some of the tribe had been forcibly relocated up to 13 times by the federal government.

During the 1848 removal from Iowa, about 2,500 people were forced to travel by wagon, on foot, and on horseback, and then later on steamboat, to Minnesota.

Through forced treaty cession, the Ho-Chunk lost an estimated 30 million acres in Wisconsin alone.

Ernest Heinemann, Wikimedia Commons

Ernest Heinemann, Wikimedia Commons

How Did The Ho-Chunk React To The Removals?

Although the forced removals were harmful in nearly every way possible, the Ho-Chunk didn’t violently resist. Instead, they resisted removal by staying home, or simply returning home, rather than engaging in the uprisings.

All in all, the Ho-Chunk were forced to give up lands in Wisconsin in 1829, 1832, and 1837. And then further removal attempts occurred again in 1840, 1846, 1850, and 1873.

But the 1837 removal was a controversial one.

Henry Lewis, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Lewis, Wikimedia Commons

The 1837 Removal Attempt

In 1837, a controversial attempted land cession occurred when the Americans offered the Ho-Chunk land in present-day Minnesota they claimed to be desirable, and gave them eight years to move—but it turned out to be eight months.

As a result, many Ho-Chunk flat out refused to leave. The Wisconsin Ho-Chunk today are the descendants of these “renegades” or “rebel faction”—those who refused to settle out west.

James Otto Lewis, Wikimedia Commons

James Otto Lewis, Wikimedia Commons

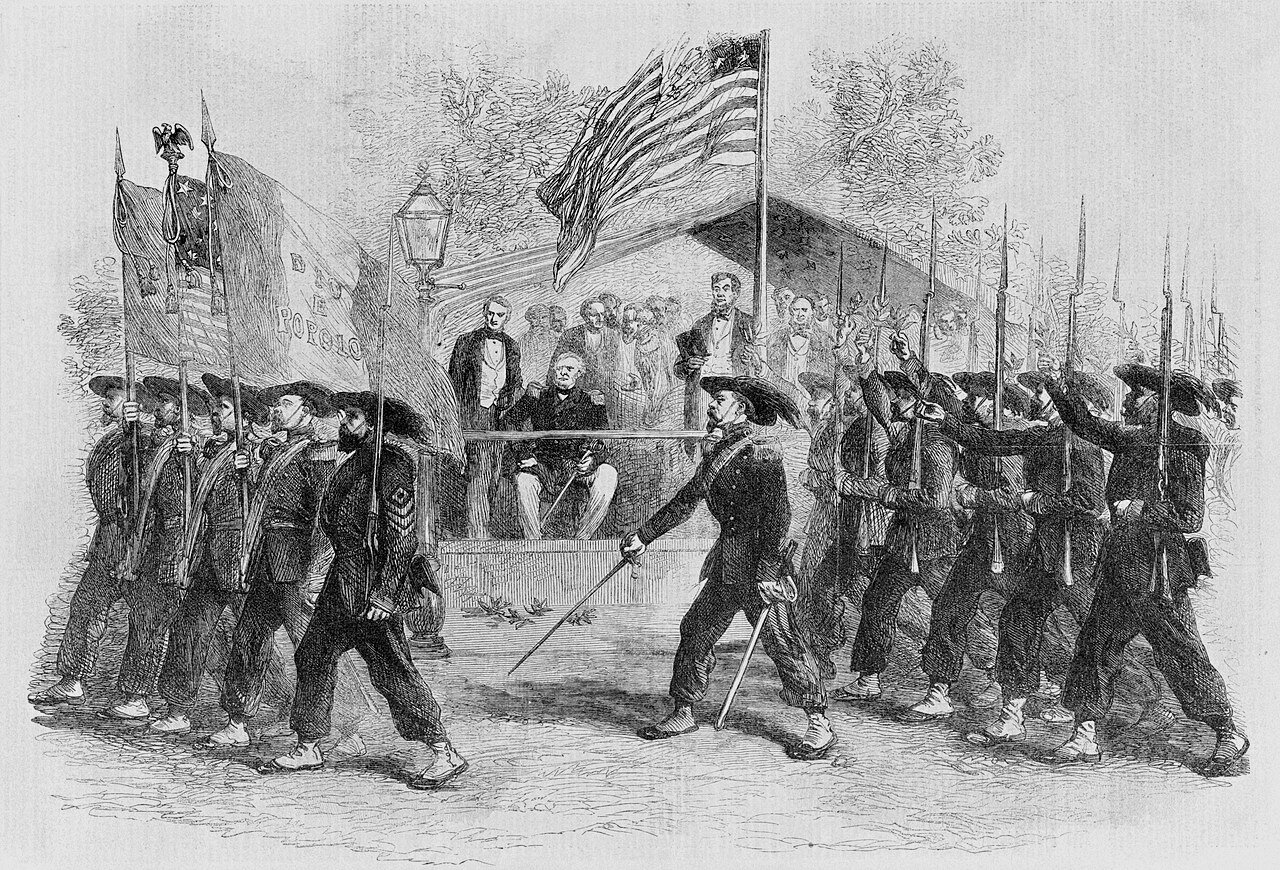

Continued Conflicts

Over the next several years, more removal attempts occurred, as well as uprisings from other tribes who were also fighting relocation. In 1861, a civil war broke out and the Ho-Chunk enlisted in the Union Army, joining Minnesota, Nebraska, and Wisconsin. And then the following year, the Sioux Uprising claimed the lives of 500 settlers. Although the Ho-Chunk were not directly involved in that incident, the Americans demanded that they be removed from the area as well.

Hostilities grew but many Ho-Chunk people still refused to move.

Frank Vizetelly, Wikimedia Commons

Frank Vizetelly, Wikimedia Commons

How Often Did They Move?

Even though some of the Ho-Chunk managed to remain in their homes through refusal, many others didn’t have the same luck. A large portion of Ho-Chunk were still being moved around. Between 1832 and 1865, the majority of Ho-Chunk were moved from Wisconsin to Iowa, then to Minnesota, and then from there to South Dakota, and then to Nebraska. For decades, the Ho-Chunk had no permanent place to call home.

And in 1863, a new threat was introduced.

Blue Earth County Historical Society, Picryl

Blue Earth County Historical Society, Picryl

The Knights Of The Forest

In 1863, the Ho-Chunk who were living in Blue Earth County, Minnesota (where they were moved to in 1855) were once again forced to leave—but this time, it wasn’t the American government.

The Knights of the Forest was a secret society hate group organized by vengeful prominent pioneer settlers in nearby Mankato. Their main purpose was to eliminate all Natives from Minnesota. And they had help, too. Blue Earth County commissioners sent for "negro bloodhounds" from the South to assist the Knights of the Forest in the removal.

The Knights carried out their plan by sending armed men to surround the Ho-Chunks' prime farmland and shoot any Ho-Chunk who crossed the line—and the results were devastating.

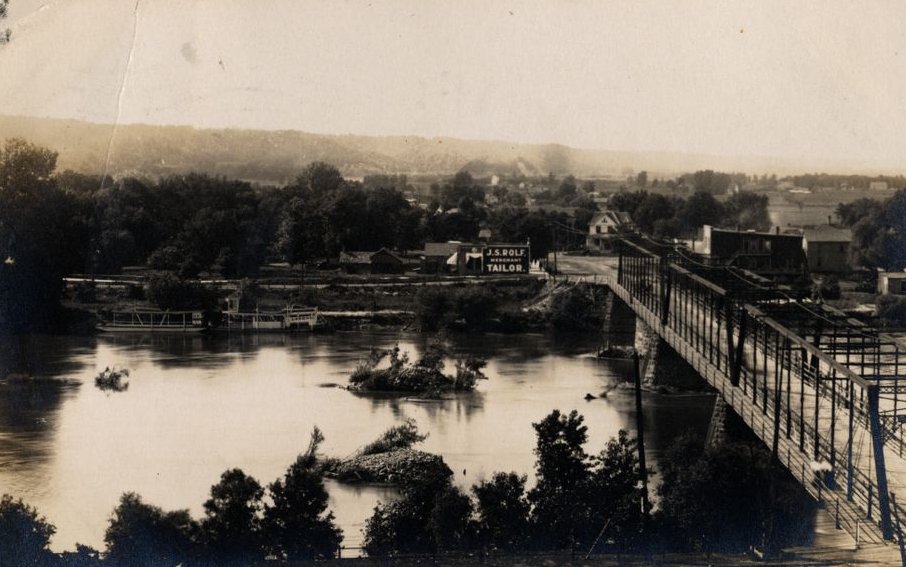

Merchant's Lithographing Company. Ruger & Stoner, Picryl

Merchant's Lithographing Company. Ruger & Stoner, Picryl

What Happened To Them?

Many Ho-Chunk lost their lives. And a whopping 2,000 of them were forcibly taken to the Crow Creek Indian Reservation in Dakota Territory. But poor conditions at Crow Creek led many Ho-Chunk to leave and go to an Omaha reservation in Nebraska instead.

In 1865, a treaty was signed and the Ho-Chunk had purchased a reservation in Nebraska. And while many Ho-Chunks remain there today, not everyone stuck around.

Where Did The Ho-Chunk Go?

For years after the relocations, many Ho-Chunk sent to Nebraska decided to go against the American government and go back home to Wisconsin anyway, to their native lands. Despite the continued roundups and removals, the Wisconsin Ho-Chunk held their ground and petitioned the US government for citizenship. And believe it or not, under the Homestead Act, some tribal members gained title to 40-acre (16-hectare) parcels of land.

Unfortunately, the land they were given was not ideal for their traditional hunting, gathering, fishing, or gardening. Not only that, fences and property signs were put up in areas where tribal members used to gather wild berries and medicinal plants, prohibiting them from access.

When Did They Become Ho-Chunk Nation?

Even still, they made the best of it, and this land eventually became an official Reservation known as the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin. Eventually, the Ho-Chunk in Nebraska gained independent federal recognition as a tribe as well, and now have a reservation in Thurston County, known officially as the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska.

But just because they had some of their land back, didn’t mean everything was okay again.

The Horror Of Residential Schools

Shortly after these reservations were officially created, the government opened up residential schools specifically for Native children. Students were expected to speak English and children as young as six years old were placed in boarding schools and not allowed to return home. As we now know, many residential schools horrifically mistreated children, causing many little ones to tragically die.

The intent was to assimilate Native children. And it had devastating effects on the Ho-Chunk culture.

Wisconsin Historical Society, Getty Images

Wisconsin Historical Society, Getty Images

How Did Their Culture Change?

Along with residential schools, the Ho-Chunk were now living on lands that could not sustain them, and so they had to change the way they lived. They began adopting modern ways of doing things, which included farming techniques, building modern houses, and wearing modern clothing. They sold their handicrafts to pay for food, water, and other resources—rather than gather and process things themselves.

By the 20th century, the Ho-Chunk saw major economic changes.

Unknown author, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

What Economic Changes Did They See?

In the 20th century, the Ho-Chunk gained access to automobiles, which amped up their craft-selling as they were able to travel further. They also took up seasonal jobs cherry-picking on local White-owned farms. And when the US entered WWII, the Ho-Chunk actually joined in and served as Code Talkers, relaying information in their ancestral language that was impossible for the Japanese to decipher. All of this brought in a necessary (but insufficient) income to support themselves in their new world.

But not once did they stop fighting for their land.

Henry Hamilton Bennett, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Hamilton Bennett, Wikimedia Commons

When Did The Ho-Chunk Become Federally Recognized?

In 1963, the Wisconsin Ho-Chunk received federal recognition, and bought back 554 acres of their land for tribal housing. And then in 1974, they won a $4.6 million judgement from the Indian Claims Commission to compensate for lands lost through fraudulent treaties.

Air Force Photo by Daniel J. Rohan Jr., Wikimedia Commons

Air Force Photo by Daniel J. Rohan Jr., Wikimedia Commons

Gaining Protection

Four years later, in 1978, the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was put into effect, protecting Indigenous children from the horrific mistreatment at residential schools. In the same year, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act was enacted, protecting the rights of Native Americans to enjoy and express their traditional religions.

Getting Their Culture Back

Slowly, the Ho-Chunk were taking back their culture. And in 1992, the nation’s flag was adopted. Its five colors all represent animals of particular clans, and have corresponding meanings in the tribe’s oral history.

And in 1994, the tribe, who were still being referred to as "Winnebago", officially changed their name back to their traditional Siouan name, "Ho-Chunk"—an incredibly important part of their history.

The Ho-Chunk Nation Of Wisconsin

The Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin is considered a "non-reservation" tribe, as members historically had to acquire individual homesteads in order to regain title to ancestral territory. They hold land in more than 13 counties in Wisconsin and have land in Illinois. But although the federal government has granted legal reservation status to some of these parcels, the Ho-Chunk nation does not have a contiguous reservation in the traditional sense.

Phillippe Diederich, Getty Images

Phillippe Diederich, Getty Images

What Are The Reservations Like Today?

While related, the two tribes are distinct, federally recognized sovereign nations and peoples, each with its own constitutionally formed government and completely separate governing and business interests. And today, the Ho-Chunk Nation owns and operates several casinos, numerous restaurants and hotels connected to the casinos, as well as numerous gas stations.

U.S. Department of AgricultureLance Cheung, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Department of AgricultureLance Cheung, Wikimedia Commons

What Is Their Culture Like Today?

Today, the Ho-Chunk are working tirelessly to bring back as many aspects of their traditional culture as possible, from clothing and handicrafts, to rituals and celebrations—and especially their language. They have now developed materials (including an iOS app) to teach and restore their ancestral language—as they only have about 200 native speakers left among their elders.

Final Thoughts

In the early 2020s, the Ho-Chunk Nation had more than 7,800 members—a number that once seemed impossible to regain. The Ho-Chunk tribe’s history is packed with tragic accounts and periods of success. Despite facing near-extinction, today they are among the federally recognized and thriving Native American tribes.

You May Also Like:

The Only Native American Tribe That Never Surrendered

Historical Photos Of The Most Fearsome Tribe In America

Historical Photos Of North America’s Powerful Warrior Tribe