This Mayan Tribe Avoided Contact For Centuries, Now They're Fighting To Survive

Near the southern border of Guatemala in Chiapas, Mexico, a tribe of people lives nearly untouched by civilization. A tribe with Mayan roots: the Lacandon Maya, who are fighting to maintain their cultural roots as escapees of oppression, without engaging many of the trappings of modern life. Many of the Lacandon Maya still live in the forests in Chiapas. Here's how they've fought to survive.

The Origins Of The Lacandon

Tracing the origins of the Lacandon was quite the task for historians, but researchers from the University of Florida's anthropology department conducted research on the remote tribe, which indicated that they formed as part of an amalgamation of various tribes in the late 18th century.

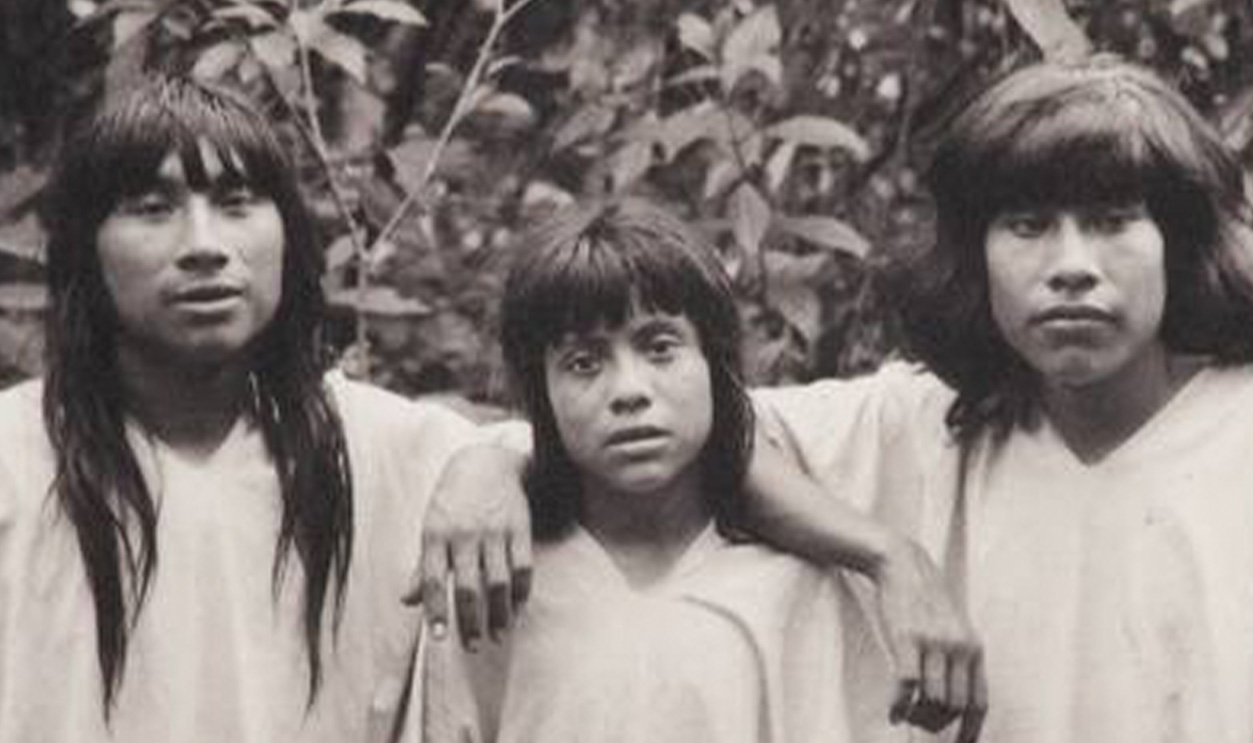

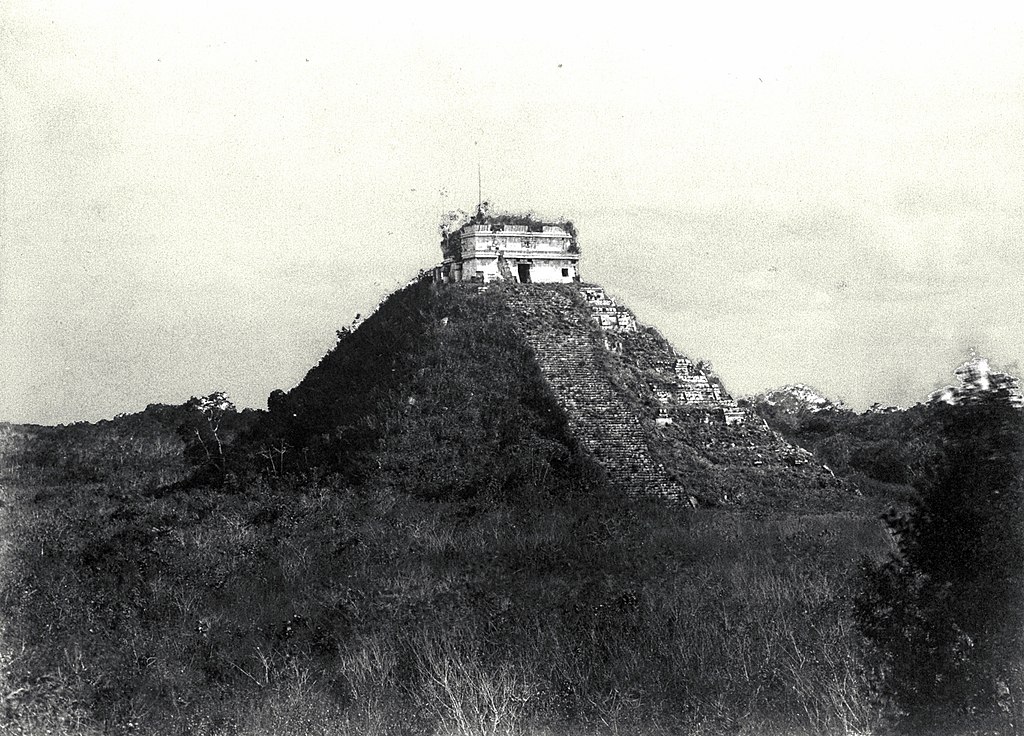

Teobert Maler, Wikimedia Commons

Teobert Maler, Wikimedia Commons

People From Everywhere

It appears as though the Lacandon originated from groups of refugees from the low-laying Mayan civilizations fleeing Spanish oppression throughout the 18th century. Left with nowhere to run, they retreated into the rainforests on the Mexico-Guatemala border.

The Ancestors: The Classic Maya

Original scholars of the issue in the early 20th century posited that the Classic Maya language, one of the oldest languages in South America, was connected to the Lacandon. The scholars thought that the Lacandones were the untouched Maya peoples, as they resided in the jungles nearby Mayan Mesoamerican pyramids. However, more recent scholarship revealed their true origins.

A Century Of Being Left Alone

Being a Lacandon in the 18th century was an introvert's dream. After fleeing marauding Spanish conquistadors, the Lacandones settled in the Campeche and Pleten regions of Mexico and Guatemala respectively, remaining free of contact with the outside world for almost a century.

Pedro Lira Rencoret, Wikimedia Commons

Pedro Lira Rencoret, Wikimedia Commons

Thriving In Isolation

Living off the land and making do with what the rainforest provided—an abundance of different food and fresh water, as well as trees to make shelters—the Lacandones lived very well off the land. While other Indigenous groups in post-colonial Mexico and Guatemala were being subjugated, the Lacandones were a free people.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Wikimedia Commons

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Wikimedia Commons

Would-Be Conquerors Scared Off By Legends

Perhaps to protect themselves or perhaps by rumors spread by would-be conquering Mexicans and Spanish settlers, the Lacandones were feared. The fairytales told by parents to their children are of wooden people and flying monkeys, which would have been quite alarming to a Spanish conquistador trying to settle in the rainforest.

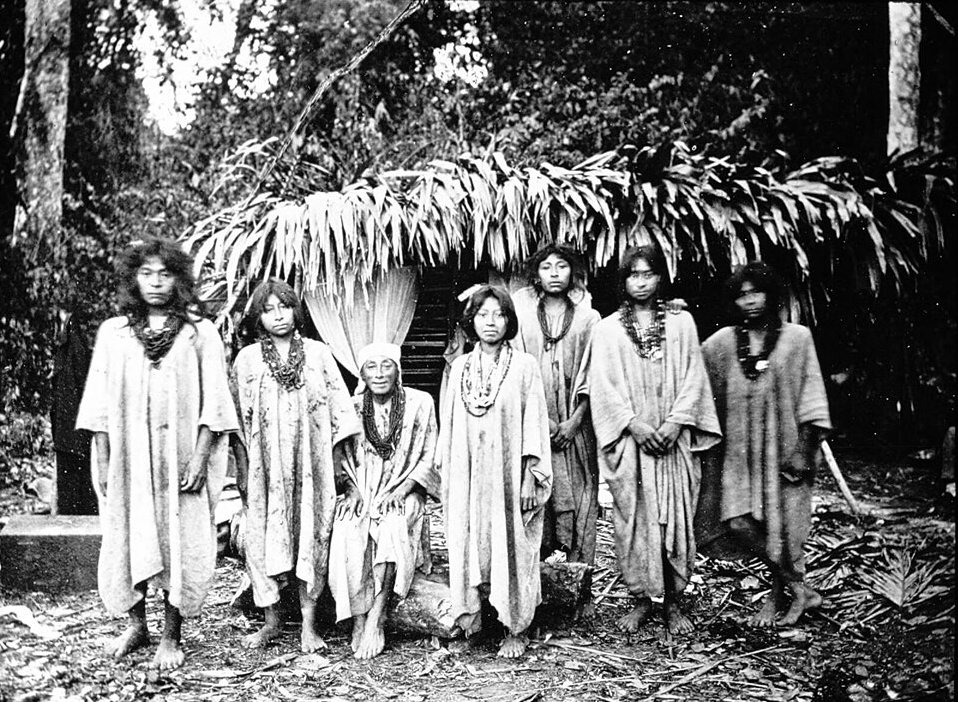

Teoberto Maler, Wikimedia Commons

Teoberto Maler, Wikimedia Commons

Building A Good, Mutually Beneficial Trade Relationship With The Outside World

Because they weren't subjugated by colonial forces, they were able to build a mutually beneficial trade relationship with the nearby European settlers, who often traded salt, metal tools, and cloth for goods that could only be sourced by the Lacandon: animal skins and furs, fruits, and timber. This mutually beneficial trade relationship, coupled with the small nature of their tribal groups, helped the Lacandon stave off colonization.

Heritage history, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Heritage history, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

The North And South Lacandon Peoples

While sharing many commonalities, the Lacandon peoples did diverge into two distinct groups, the North Lacandon, who live in Najá and Mensabäk and are still very connected to their Maya ancestry, and the Lacanhá Chan Sayab, a tribe of Southern Lacandones who wear Western clothing and have more modern dwellings.

Lacandon Traditions

While they no longer uphold some of these traditions, thanks to colonialism, some of the Lacandon traditions included building homes as thatched huts, with (or without) walls and supported by thin poles. All timber would have been sourced from their surroundings. As there were typically many Lacandon people sharing a single dwelling, any possessions would have been stored in the thatched roofing, with food stored in baskets on the roof.

Lacandon Clothing

Older Lacandon males and females would typically wear knee-length tunics, with the women wearing skirts underneath their tunics. Meanwhile, Lacandon from the south would wear ankle-length tunics.

How That's Changed

While many Lacandon still occupy the rainforest of their ancestors, their thatched roofing has been replaced by tin and their wall-less or mud-walled dwellings have been replaced by concrete walls. Today, many of the South Lacandon wear Westernized clothing, despite still living in the rainforest or spending a great deal of their time there.

The Lacandons' Luck Runs Out

By the start of the 19th century, the Lacandons' efforts to stave off European conquest (or total annihilation) had waned, as farmers and ranchers armed with weapons invaded their forestlands, causing the unarmed and outnumbered Lacandones to retreat deeper into the forest.

More Conflict, More Encroachment, Less Control

As the 19th century wore on, the Lacandones found themselves unable to resist the ever more frequent incursions onto their land by Mexican farmers and ranchers in the south and Guatemalans in the northern region of Chiapas. This led to disease, loss of territory, and the influence of Western and South American culture upon the previously isolated peoples.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Wikimedia Commons

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Wikimedia Commons

A New Century Brings Further Encroachment

Having previously been set up in small, well-dispersed housing made from mud and thatched roofs, the Lacandones were fast losing territory, with the 1950s and 1960s bringing mass migration into the rainforest by Guatemalan peasant farmers, while the government of Guatemala actively encouraged the incursions.

ProtoplasmaKid, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

ProtoplasmaKid, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Airstrip At Lacanja Chansayab

In 1957, a US Baptist missionary who had been visiting the village of Lacanja Chansayab, in an apparent effort to convert the locals, ended up building a huge airstrip in land already affected by logging. This airstrip allowed more visiting preachers to the remote tribe.

ProtoplasmaKid, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

ProtoplasmaKid, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mass Logging Begins

As industry took hold in Guatemala and Chiapas, logging the timber from the Lacandon rainforest became a primary objective for local and federal governments of the 20th century. While providing wage-paying jobs to the Lacandones who did not resist, the scourge of industry all but destroyed the symbiotic relationship between the Lacandones and the rainforest.

Charnay, Désiré, Wikimedia Commons

Charnay, Désiré, Wikimedia Commons

Mahogany And Cedar Exports Among Chief Culprits

The two trees that were most sought after by logging companies in Mexico and Guatemala were mahogany and cedar trees, chopped down to be sold to the United States, the UK, and Europe. Where the trees came down, roads went in, allowing for migrant farmers who had once been resistible by the Lacandones to come and set up shop.

J.M.Garg, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

J.M.Garg, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Lacandones Are Pushed Deeper Into The Forest

The Lacandones retreated even further into their ever-shrinking parcel of forest land, until a landmark ruling in 1971 by the Mexican President protected 614,000 hectares of land, reserving it for the Lacandon peoples. 10 years later, other religious groups would begin missionary work into the Lacandon Jungle, attempting to convert people to Christianity, namely Catholicism and Protestantism.

Standley, Paul Carpenter, Samuel J. Wikimedia Commons

Standley, Paul Carpenter, Samuel J. Wikimedia Commons

The 1978 Establishment Of The Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve

Further expanding the protected lands granted to the Lacandones, the government of Mexico created the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve. Resentment among other Native American tribes boiled over, eventually resulting in the Zapatista Uprising of 1994.

Darij & Ana, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Darij & Ana, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The First Road Connects North And South Lacandones

In 1979, the very first road was installed in the Lacandon Jungle, which connected the northern and southern regions for the first time. Prior to this, contact between Northern and Southern Lacandones was very limited. Despite them sharing a common ancestry, they spoke different dialects of Yucatec Maya and referred to themselves as the "true people". The road opened communication, trade, and intermarriage between the two groups for the first time.

AlejandroLinaresGarcia, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

AlejandroLinaresGarcia, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Raw Deal For The Lacandon As A Result Of Logging

By the early 1970s, many other Indigenous groups had been given land in the Lacandon Jungle, putting their semi-commercial practices at odds with that of the Lacandon, who had always practiced sustainably taking what they needed from the rainforest. This, along with oil deposits being found in the rock of the rainforest, meant that the protective Lacandon people couldn't hold out much longer against the tides of capitalism and industrialism.

Thelmadatter, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Thelmadatter, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Lacandon Are Not Paid Their Fair Share

While the Mexican Government would set up corporations in the late 1970s to sell contracts to the Lacandon communities in the rainforest, the government controlled the majority of royalties paid—the Lacandon only received 30%, meanwhile the Mexican Government pocketed 70% of the earnings.

Conversions Begin

By the late 1970s, missionary work by Christian groups like the Summer Institute of Linguistics translated the Bible into Lacandon, or Jach-t'aan—the primary language of the Lacandones. This made conversion to Christianity much easier, as the remaining Southern Lacandones slowly converted.

The Zapatista Uprising Of 1994

The Zapatista Uprising of 1994 was a 12-day uprising in Chiapas, Mexico, against the enacting of the North American Free Trade Agreement, which had recently been agreed upon by the United States, Canada, and Mexico. 3,000 members of the rebel movement, called the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, occupied towns and cities in Chiapas, destroying land records and releasing prisoners.

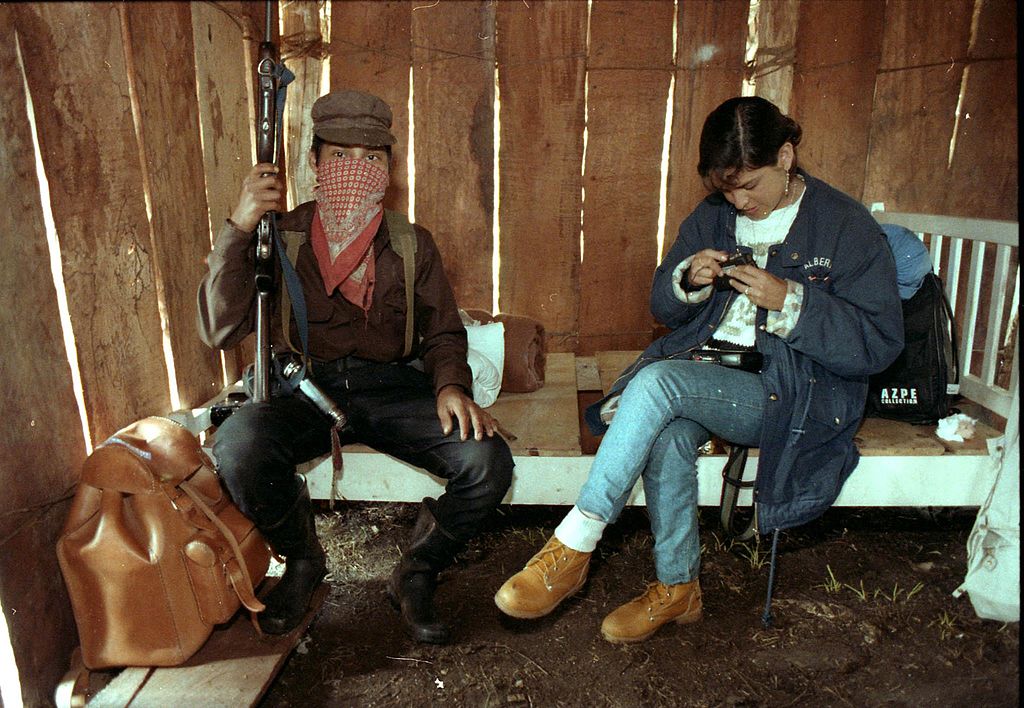

Unknown Artist, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Mexican Army And Police Are Brought In

The Government of Mexico responded swiftly to the eco-warriors' uprising, bringing in 30,000 to 50,000 Mexican Army and Police forces, and resulting in a series of shootouts that would lead to 153 deaths. After 12 days of violence, the Mexican Government and the leaders of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation brokered a ceasefire on January 12, 1994. It's thought that some of the rebels involved were members of the Lacandon tribe.

Julian Stallabrass, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Julian Stallabrass, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Modern State Of The Lacandon

Now reduced to an ever-shrinking part of the rainforest, with encroachment seemingly a fact of life, one Lacandon resident speaking to the BBC stated, "There are more churches than people," and that his grandmother "doesn't speak of the old religions as they're sinful". It's a further indication of how much the cultural and religious history of the Lacandon has been lost.

Julian Stallabrass, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Julian Stallabrass, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Reliance On Tourism For Sustenance

Unlike their northern counterparts that have remained more true to their original Mayan roots and practices, Southern Lacandon have been well and truly Westernized, including opening up their once-sacred home to tourists. Cabins (though primitive) are built to allow tourists to stay, and there's even a village shop that sells Coke. There's a small restaurant and even a shared computer in one village of Lacandones.

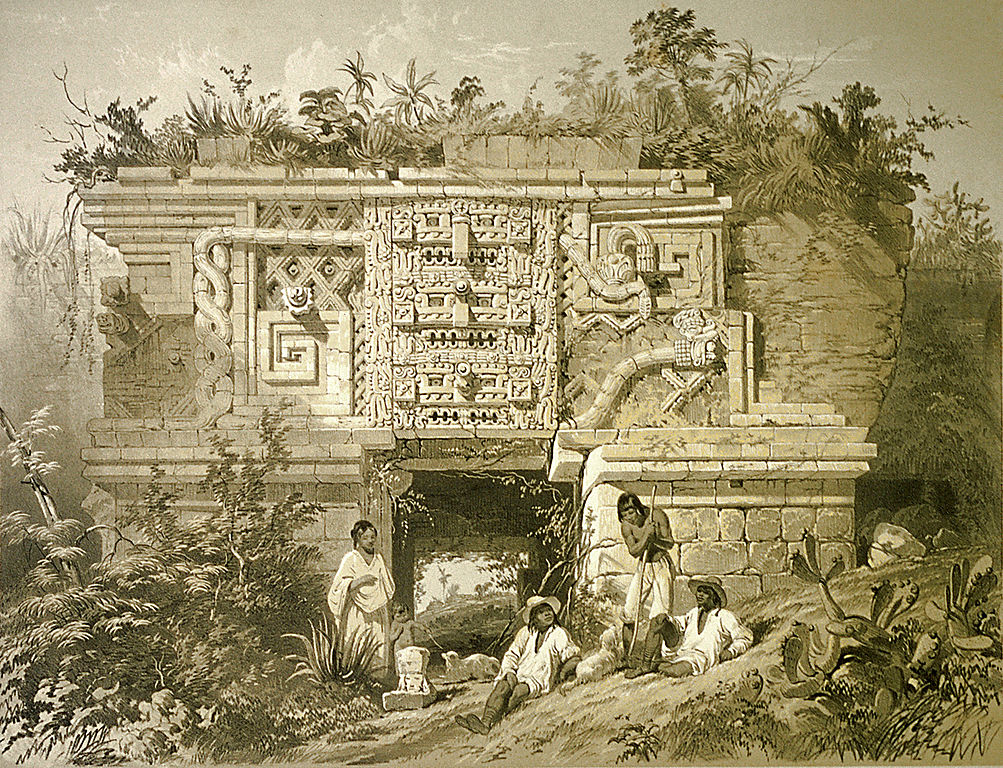

Julian Stallabrass, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia CommonsThe Lost Maya City Of Lacanja

Julian Stallabrass, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia CommonsThe Lost Maya City Of Lacanja

In further exploration with the BBC, the Lost Maya City of Lacanja was revealed. A huge stone structure jutting out from the sea of green trees and moss that surrounded it, the Lost Maya City of Lacanja was discovered by archaeologists in the 1930s, but has never been excavated. This is due to the logistics of getting an archaeological team in there and legal challenges over who owns the rights to the stunningly-preserved piece of history.

Aliman5040, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Aliman5040, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Can A Return To Origins Save The Lacandon?

Despite the presence of the internet, Coca-Cola, and a bustling tourism industry, the Lacandon are still very much attached to the ideas of land stewardship. They believe that conservation is their highest calling and that their future lies somewhere in between modernity and embracing (or re-embracing, as it were) the history and culture that kept them alive and attune to the rainforest for centuries.

You May Also Like:

Legends Who Vanished After The Civil War