The City Of Gold

Since the colonization of the Americas, rumors of a golden city hidden in South America have remained a popular legend. However, the original explorers and conquerors who heard of this city didn’t see it as mere legend. Unfortunately, their insatiable greed and drive for discovery would lead only to tragedy on their cursed expeditions.

The First Rumors

As far back as the 15th century, European explorers were spreading rumors that untold riches lay somewhere in the Western hemisphere. When Christopher Columbus arrived in the New World, he became convinced he had landed in a place of such wealth when he saw the Indigenous people wearing golden accessories. This belief wouldn’t end with him.

Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, Wikimedia Commons

Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, Wikimedia Commons

Vague Origins

In the early 1500s, a German conquistador named Ambrosius Ehinger invaded Venezuela. Like Columbus, Ehinger noticed many of the gold relics among the Indigenous people but later discovered their source. He was told of a region in the mountains called “Xerira” that supplied all the gold he could see.

Revista de Estudios Culturales, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Revista de Estudios Culturales, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Corroborating Stories

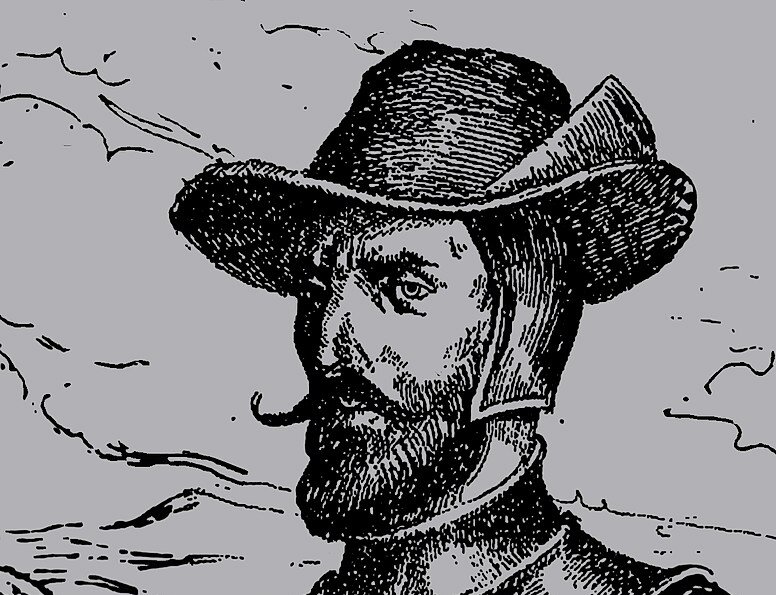

Around the same time, conquistador Diego de Ordaz took a group of Kalina people captive and learned some interesting information. According to the prisoners, the Meta River would eventually lead to a region ruled by a “valiant, one-eyed” King, where the conquistadors could fill their boats with gold. Although Ordaz never found it, the legend persisted.

Antonio de Herrera, Wikimedia Commons

Antonio de Herrera, Wikimedia Commons

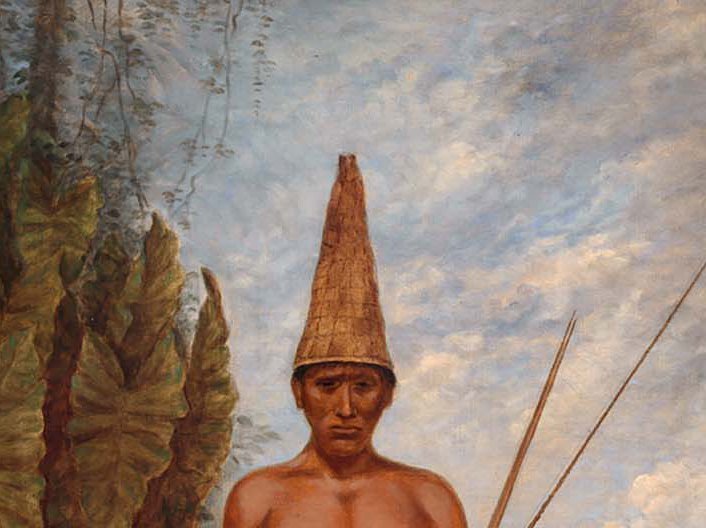

The Name’s Precursor

In 1534, when Quito was still an Incan city, the conquistador Sebastián de Belalcázar invaded and subjugated it. Afterward, an imprisoned Indigenous chief described his homeland, revealing that he wasn’t Incan. Belalcázar and his men referred to the chief as “El Indio Dorado,” or “The Golden Indian,” likely due to him wearing gold adornments.

Unknown Author, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The First Usage

Just five years after conquering Quito, Belalcázar found himself in a more dire situation. Learning that a warrant was out for his capture, he fled the city, eventually going to Popayán before heading east. Escape seemingly wasn’t his only motive, as his treasurer recorded that they had gone "in search of a land called El Dorado".

Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

A King In Gold

By 1541, the El Dorado legend began to cement itself among Europeans, furthered by the writings of Spanish historian Oviedo. He wrote about the local stories he heard, especially concerning a very wealthy Indigenous ruler, said to cover himself from head to toe in gold dust.

Coriolano Leudo Obando, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Coriolano Leudo Obando, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Name Returned

Oviedo’s records had support from the poet Juan de Castellanos, who wrote an account of Belalcázar’s interrogation of an Indigenous man. The man claimed to be from Bogotá, a place filled with treasure and ruled over by a wealthy King. Allegedly, this King performed a ceremony where he covered himself in gold dust and offered gold objects to a nearby lake. This legendary King was therefore nicknamed “El Dorado,” the Spanish word for “golden”.

Ricardo Moros Urbina, Wikimedia Commons

Ricardo Moros Urbina, Wikimedia Commons

Meeting The Omagua

As the legend of El Dorado spread, more and more conquistadors joined the hunt, including Governor Gonzalo Pizarro and Francisco de Orellana. In 1541, the two journeyed east of Quito before being forced to stop and split up. Eventually, Orellana abandoned Pizarro and met the Omagua, who told him of a prosperous people further inland.

Dominio publico, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dominio publico, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Familiar Faces

The Omagua people have popped up many times in connection with El Dorado, including in 1543, with German explorer Philipp von Hutten. After speaking to the Indigenous people near the Guaviare River, who relayed the familiar story of a land of riches, he was led to the Omagua. While they weren’t what he was looking for, they were still a big part of the legend.

Unknown Author, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Prevailing Theory

As the 1560s rolled around, rumors of the legendary El Dorado—whether a man or place—had spread among the settlers in South America. Among the Spanish in Peru, it was widely accepted that wherever the golden kingdom was, it belonged to the Omagua.

Antonio Zeno Shindler, Wikimedia Commons

Antonio Zeno Shindler, Wikimedia Commons

He Got Permission

Following an almost decade-long suspension of all expeditions, conquistador Pedro de Ursúa received permission for an expedition. In 1560, Ursúa set off into the Amazon in search of El Dorado. This was spurred on by further reports that reached him.

Miniature of XVI century, Wikimedia Commons

Miniature of XVI century, Wikimedia Commons

More Omagua Stories

Ursúa had become impassioned for the search of El Dorado after hearing the accounts of several Indigenous Brazilians who had traveled to Peru. These travelers spoke of their time among the Omagua, detailing an extensive trading network and "the inestimable value of their riches”.

Hessischer Rundfunk, Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972)

Hessischer Rundfunk, Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972)

Another Failure

Embarking on his Amazonian journey, Pedro de Ursúa took a force of 370 men. However, this undertaking only lasted a few months, as Ursúa was slain during a mutiny in January 1561. Those who took charge of the expedition had no interest in the legend and immediately gave up searching for the hidden kingdom.

Hessischer Rundfunk, Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972)

Hessischer Rundfunk, Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972)

A New Expedition

Six years after Ursúa’s doomed expedition, three other explorers took up the quest. Diego Soleto and Pedro Maraver de Silva joined Martín de Poveda, who led them along the Andes Mountains, departing from Chachapoyas. At this point, they abandoned a previously held assumption.

Gerd Breitenbach, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Gerd Breitenbach, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Better Directions

Legends stemming from Belalcázar’s initial invasion of Quito hinted at El Dorado’s location being hidden somewhere near Bogotá. However, after exploring the area, Martín de Poveda concluded that this was untrue. Instead, he and his men learned from the Indigenous people that the place they were looking for was likely closer to the eastern Llanos River.

Alejo Rendón, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Alejo Rendón, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Joined The Search

In 1569, another conquistador named Jiménez de Quesada grew inspired by Poveda’s quest. Receiving permission from the King, Quesada took an army of 300 strong on an expedition to search the plains east of New Granada. Fortunately, he wasn’t exactly new to the life of an explorer.

Coriolano Leudo Obando, Wikimedia Commons

Coriolano Leudo Obando, Wikimedia Commons

It Wasn’t His First Rodeo

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada had been in the New World for several decades and already had an extensive career of exploring and conquering, known for overtaking the Muisca people. He was also no stranger to the El Dorado legend, as before his 1569 expedition, he had already led an—albeit failed—search for the fabled kingdom in 1536.

Ricardo Gómez Campuzano, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ricardo Gómez Campuzano, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Made Little Progress

Unfortunately for Quesada, failure would continue to follow him. After sending no reports or communication for two and a half years, he returned to Bogotá. His army of 300 had dwindled to 50 men, defeated and barely surviving, as they had achieved virtually nothing. Still, Quesada did not abandon the search.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

He Left Everything To Him

Jiménez de Quesada never found El Dorado, and eventually, he lost his chance when he passed on in 1579. His son-in-law, Antonio de Berrio, was another Spanish explorer and the inheritor of Quesada’s title and estates. Of course, there was one stipulation.

Mglandasteam, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mglandasteam, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

There Was A Catch

Quesada’s search for El Dorado had become an obsession, so much so that it continued even after he perished. Quesada’s will specified that whoever was his successor would have to continue the hunt, looking for El Dorado—in his words—“most insistently”. Naturally, Antonio de Berrio was in no place to refuse.

Luis Alberto Acuña, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Luis Alberto Acuña, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Began His Journey

In accordance with Quesada’s will, Antonio de Berrio embarked on his search for El Dorado in the early 1580s. Believing the true location of the hidden kingdom to be somewhere in the Guianas, Berrio and his men crossed the Llanos. Along the way, he still needed assurance that he was on the right path.

Haroldarmitage, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Haroldarmitage, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Were Coerced

During their search, Berrio and his men captured several Indigenous people in the hopes that they could lead to El Dorado. While interrogated, these prisoners seemingly confirmed Berrio’s belief that the Guianas was home to settlements with “great riches of gold and precious stones" and a large lake called Manoa.

Neil Palmer, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Neil Palmer, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Couldn’t Go Any Further

Although determined to succeed where his predecessor had failed, Berrio’s first expedition fared no better. After crossing over the Orinoco River, they found that the elements were too much for them, and Berrio made the difficult decision to turn home. This didn’t stop his determination, though.

Pedro Gutiérrez., CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Pedro Gutiérrez., CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Third Time’s The Charm

After a second, equally unsuccessful attempt—during which his men betrayed and deserted him—Berrio launched a third expedition in 1590. Following the Caroní River, he hoped to reach its confluence with the Orinoco and enter the Guianas. However, he and his crew lacked the manpower, so they followed the river to the Atlantic Ocean instead.

AxeEffect, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

AxeEffect, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

A New Visitor

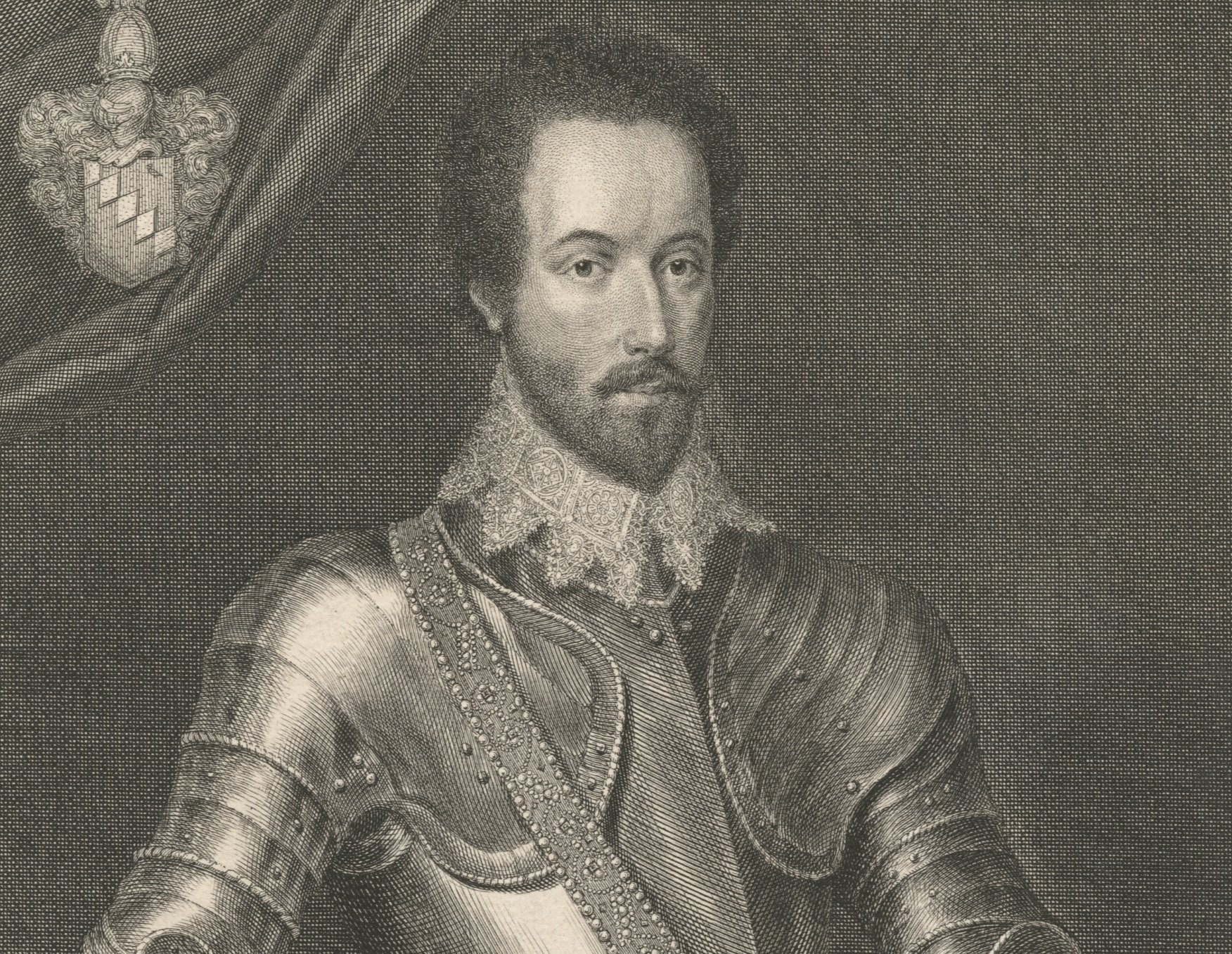

Having failed his three expeditions for El Dorado, Berrio and his men ended up at the Atlantic Ocean, where they founded the city of San José de Oruña in Trinidad. Only three years after this, in 1595, famed English explorer Sir Walter Raleigh sailed his fleet to the island—where he learned some lucrative information.

National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

They Told Him Everything

Being a shrewd man, Raleigh suspected that Trinidad’s newest inhabitants could be a valuable source of knowledge—and he knew how to get it. Acting as friendly as possible, Raleigh invited the Spaniards aboard his ship to trade and make merry. Under the influence of drinking, the Spanish revealed everything they knew, including Berrio’s exploits.

James Posselwhite, Wikimedia Commons

James Posselwhite, Wikimedia Commons

He Caught Them By Surprise

Raleigh’s betrayal was quick and cunning, and a couple of weeks after his arrival, he besieged San José de Oruña without warning. During this battle, he took Berrio captive and interrogated him for any information he could. Only after this did Raleigh reveal the goal he had been set on for a long time—to find El Dorado.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

He Set Out

Without time to waste, Raleigh set off through the Orinoco delta. Since the channels were too narrow, he had one of his ships modified to fit through before embarking on his search. However, he immediately found out how unforgiving the New World could be.

Milito, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Milito, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Got Lost

As Raleigh and his men navigated the delta, the waters around them became increasingly confusing and treacherous. He would refer to the channels as a “labyrinth of rivers,” which kept them occupied for far longer than he wished. Eventually, though, he and his crew made it through and started their journey up the Orinoco.

Ruzzytaa, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ruzzytaa, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Met A Helpful Ally

Eventually, Raleigh reached the point that had proved Berrio’s downfall—where the Orinoco met the Caroni. Here he met an unexpected ally in Topiawari, an Indigenous chief. Raleigh was once again courteous and in return, Topiawari relayed some beneficial knowledge.

Dilankf, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dilankf, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Felt Assured

Topiawari spoke of the fate that had befallen him and his people. According to him, they encountered a hostile tribe carrying a great amount of gold with them, and who came from the west. Many explorers, including Raleigh, believed that El Dorado was full of escaped Incas from Peru, and this story seemed to corroborate the theory.

Joseph Simpson, Wikimedia Commons

Joseph Simpson, Wikimedia Commons

It Was Too Strong

Continuing his adventure, Raleigh and his men found the mouth of the Caroni—and its current. Halted by the dangerous waters, he sent scouts ahead on land, some of whom discovered a great lake at the Caroni’s source containing vast amounts of gold. However, this was fruitless as the river impeded any process, causing Raleigh to abandon his quest.

Berrucomons, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Berrucomons, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Tried Again

Raleigh had no choice but to give up his expedition, yet he persisted, even if it took longer than expected. Over 20 years after his failure, he went to King James I and assured the ruler that he could bring back hordes of gold from the Guianas. King James granted Raleigh permission for an expedition, but it came with a restriction.

John de Critz, Wikimedia Commons

John de Critz, Wikimedia Commons

He Was Warned

During the early 1600s, England and Spain were not in conflict, but relations between the two countries were strained. As such, when Raleigh received permission to launch his expedition, King James gave him one stipulation. Knowing Raleigh’s previous activities, the King ordered the explorer not to attack any Spanish in the area.

Paul van Somer I, Wikimedia Commons

Paul van Somer I, Wikimedia Commons

He Sent A Team

It had been two decades, but Raleigh returned to the New World with a refreshed determination. As soon as they arrived, he dispatched a group led by Lawrence Kemys to find the spot they were previously forced to abandon. However, Kemys had ideas of his own.

William Segar, Wikimedia Commons

William Segar, Wikimedia Commons

He Went Rogue

Against the orders of both Raleigh and King James, Lawrence Kemys laid siege to Santo Tomé de Guayana, a Spanish outpost. Also in the battle was Raleigh’s son, Walter, who perished. Although Kemys survived this and took control of the outpost, he was far from happy with this victory.

National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

He Was Ashamed

Kemys and his men returned to Raleigh’s ship, heads heavy with shame. Beyond the fact that they had broken England’s treaty and caused the demise of Raleigh’s son, they also failed to locate the gold. Unable to live with his guilt, Kemys took his own life, and Raleigh would soon meet his own fate.

Popular Graphic Arts, Wikimedia Commons

Popular Graphic Arts, Wikimedia Commons

He Faced Consequences

Responsible for Kemys’ deeds, and with nothing to show King James as proof there was ever any gold, Raleigh returned to England to face judgment. Sadly for him, the courts were not sympathetic to his plight, and he was found guilty. Sir Walter Raleigh went to his execution in 1618, having never found El Dorado.

There Are Still Believers

After all these centuries, the exact truth and location of El Dorado remains a mystery. Many believe it’s still out there, or at least, that the legend has a real basis. Historians like Warwick Bray argue its veracity, pointing out that the Muisca people who spoke of the fabled golden King’s ceremony had seen it first-hand.

Pedro Szekely, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Pedro Szekely, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Others Aren’t Convinced

On the other hand, some are more doubtful that anything like El Dorado existed in the first place. Many other historians, such as John Hemming, agree that the conquistadors fabricated the entire legend, one reason being to excuse their expansion into Indigenous territories and theft of Indigenous artifacts.

Unfortunately, such a city as described by the legend has never been found, so the truth remains impossible to know for sure.