Washington’s Moral Divide

Just a stone’s throw from the nation’s capital, Mount Vernon is home to one of America’s biggest contradictions. Here is the intriguing story of how the “Founding Father of the United States” oversaw hundreds of those who were enslaved.

Virginia’s Slave History

Slavery started Virginia in 1619 when the first Africans landed at Point Comfort. At first, some enslaved people who became Christians were able to win their freedom. But by 1667, Virginia made it a law that getting baptized wouldn’t allow you to be free anymore.

Wenceslaus Hollar, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Wenceslaus Hollar, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

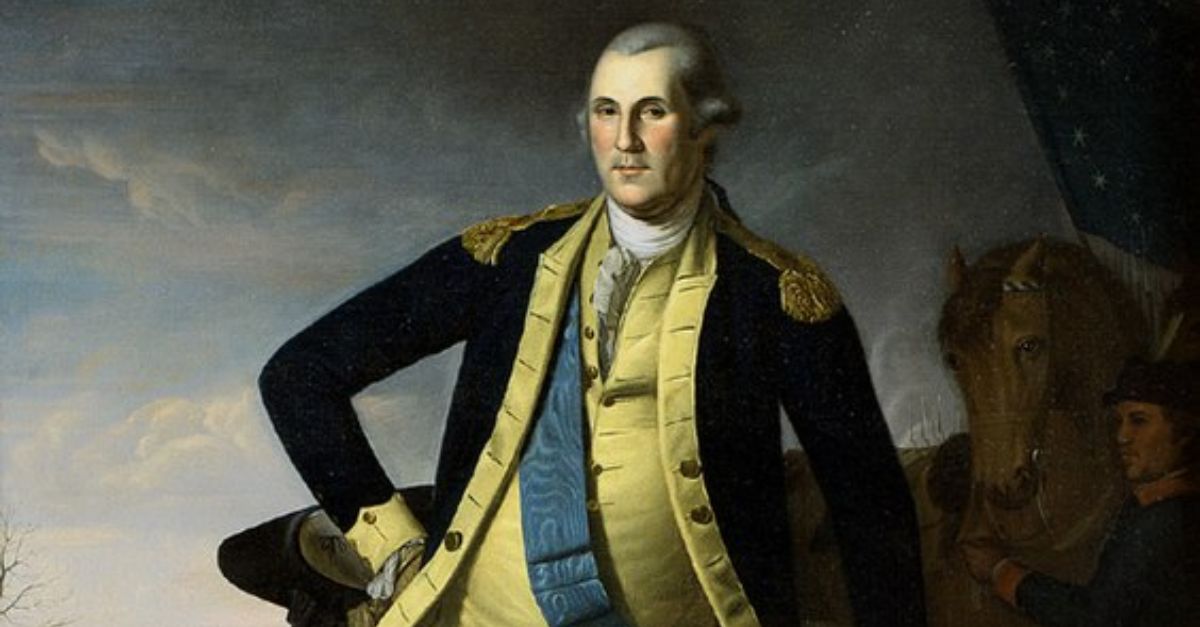

Early Inheritance

George Washington was entitled a slave owner when he was just eleven years old after his dad died in 1743. He inherited ten enslaved people and Ferry Farm as part of the deal. Washington himself grew up in Virginia’s plantation culture.

Junius Brutus Stearns, Wikimedia Commons

Junius Brutus Stearns, Wikimedia Commons

Mount Vernon Acquisition

After his brother Lawrence’s death in 1752, Washington leased Mount Vernon from Lawrence’s widow. After acquiring the estate entirely in 1761, he took command of more enslaved laborers who kept up the growing plantation activities.

Gustavus Hesselius, Wikimedia Commons

Gustavus Hesselius, Wikimedia Commons

Marriage Expansion

Washington’s marriage to Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759 really uplifted his slave holdings. He ended up with control over eighty-four “dower” slaves from her estate. Even though he couldn’t legally own them, he was the one in charge of their work.

Junius Brutus Stears, Wikimedia Commons

Junius Brutus Stears, Wikimedia Commons

Early Purchases

So, between 1752 and 1773, the man actively expanded his enslaved workforce. He purchased at least seventy-one more people. Basically, he wanted strong, healthy workers with good teeth and countenance, while he treated them primarily as business investments.

Agricultural Transition

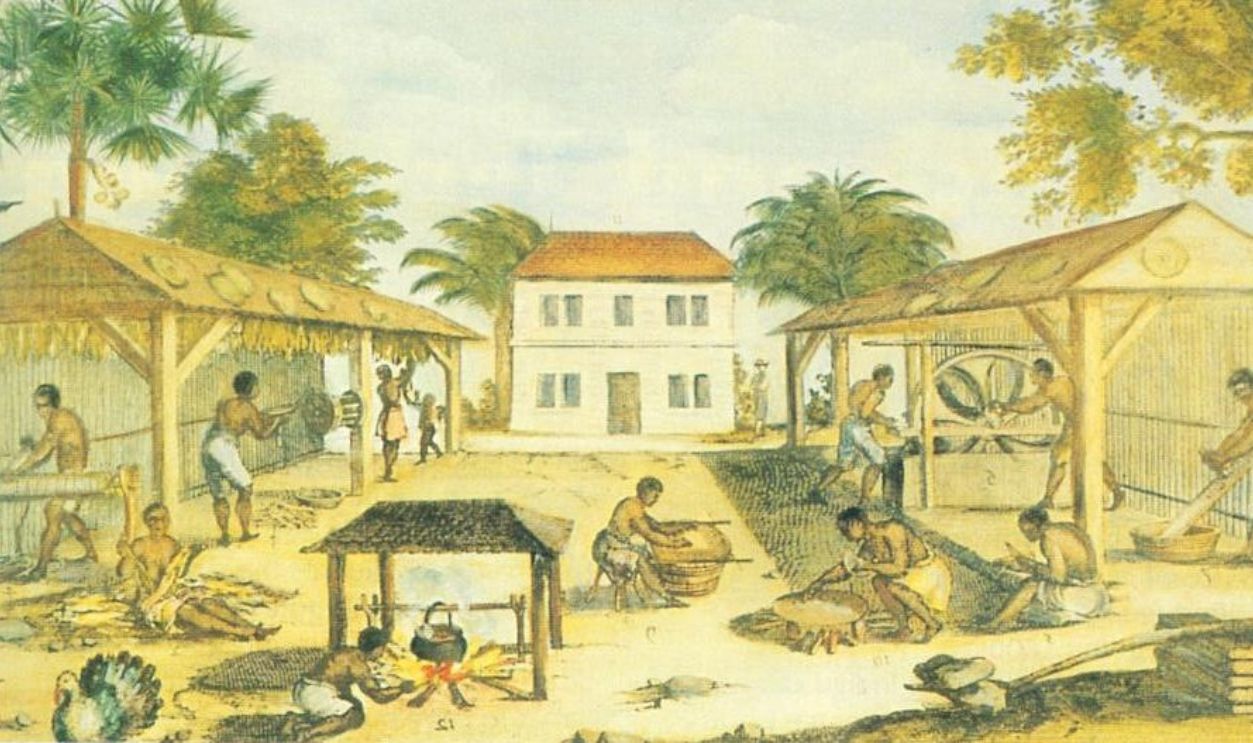

Sometime in the year 1766, Washington changed Mount Vernon’s operations from tobacco to grain cultivation. This significant shift required the workers to learn and cultivate diverse skills, like livestock management, carpentry, spinning, and other specialized tasks.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Workforce Organization

Washington organized Mount Vernon’s population across five farms. The central Mansion House Farm was home to domestic servants and skilled craftsmen. Besides, there were four outlying farms that provided employment for field workers in crop production.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Work Conditions

Those under his rule had to work six days a week from dawn to dusk. They only had Sundays off. During his residence, Washington personally inspected businesses and enforced strict monitoring through farm managers. He wanted precise work standards.

Attributed to John Rose, Wikimedia Commons

Attributed to John Rose, Wikimedia Commons

Work Conditions (Cont.)

Domestic slaves did not always get Sundays and holidays off. They were often expected to begin work early and continue working into the evenings. The others would receive a day off on Easter and Whitsunday, and also some three or four days off on Christmas.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Wikimedia Commons

Mansion House Quarters

At Mansion House Farm, these people lived in a two-story frame building until 1792, when Washington replaced it with brick wings. The new quarters now had four 600-square-foot communal rooms with bunks and were home to mainly male workers.

Tim Evanson, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Tim Evanson, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Earning Opportunities

Some enslaved people managed to make a little cash by getting tips from visitors, taking on special jobs, or selling stuff they made and produced at the market in Alexandria. They used this money to buy nicer clothes, household items, and more food.

Colonial Williamsburg, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Colonial Williamsburg, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Earning Opportunities (Cont.)

Washington would also occasionally reward his workers with cash for good service, as he did for three workers in 1775. They could even earn money by caring for breeding horses. Similarly, Hercules, the presidential chef, earned extra by selling kitchen leftovers.

Eugenefbanks, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Eugenefbanks, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Food And Clothing

It is believed that workers kept tiny garden plots to grow vegetables and supplement the minimum supplies of cornmeal and herring that Washington gave. Basic clothes were also included in the annual clothing allowances for all, but domestic workers got better ones.

Wheeler Cowperthwaite, CC BY-SA 2.0,Wikimedia Commons

Wheeler Cowperthwaite, CC BY-SA 2.0,Wikimedia Commons

Marriage Recognition

Even though Virginia law didn’t recognize marriages among captives, Washington still supported them. By 1799, about two-thirds of the adult slaves at Mount Vernon were married, but where they lived was based more on work requirements than on their family ties.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture/New York Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture/New York Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

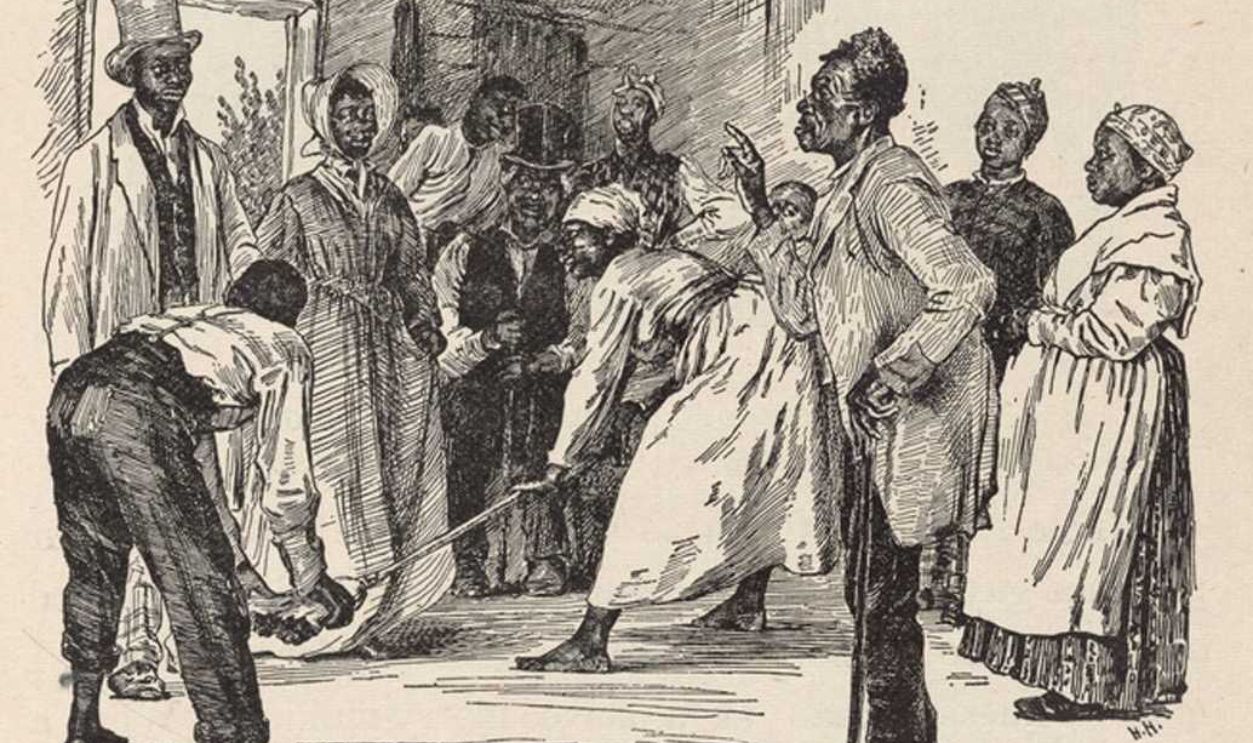

Family Separation

It is reported that out of the ninety-six married slaves at Mount Vernon in 1799, only thirty-six were actually living with their spouses. Thirty-eight had partners on different farms at Mount Vernon, and twenty-two were married to folks on other plantations.

Multigenerational Bonds

Isaac, Washington’s head carpenter, and his wife Kitty were an example of complex family networks. Living at Mansion House Farm, they had nine daughters, four of whom got married. They then expanded family connections across different farms with three grandchildren.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Cultural Preservation

So, Mount Vernon’s serf community maintained African cultural traditions through storytelling, including Br’er Rabbit tales. Some even practiced traditional religious rituals. The others adopted Christianity through Baptist, Methodist, and Quaker influences.

Edward W. Kemble (1861–1933), Wikimedia Commons

Edward W. Kemble (1861–1933), Wikimedia Commons

Interracial Relations

In 1799, twenty mixed-race people lived at Mount Vernon, and it seems they came from relationships between white workers and enslaved women. Names like Davis, Young, and Judge point to their parentage. Sometimes, the white workers would take advantage of vulnerable women and bore offspring this way.

Agostino Brunias, Wikimedia Commons

Agostino Brunias, Wikimedia Commons

Daily Resistance

Mount Vernon’s residents regularly resisted by stealing food, tools, and clothing. These acts were so common that Washington considered them normal waste. However, he did implement strict controls, like the need for seamstresses to account for fabric scraps.

Feigned Illness

Another report says that the workers would often pretend to be sick to avoid work. When Washington was away as President (1792–1794), the reported sick days increased tenfold compared to 1786. This made him grow doubtful about these illness claims.

Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

Work Slowdowns

The workers would also annoy Washington by purposely dragging their feet or breaking tools while working. Carpenters who could get work four times more done took forever to finish easy jobs when they were on their own. Seamstresses would also slow down when Martha wasn’t around.

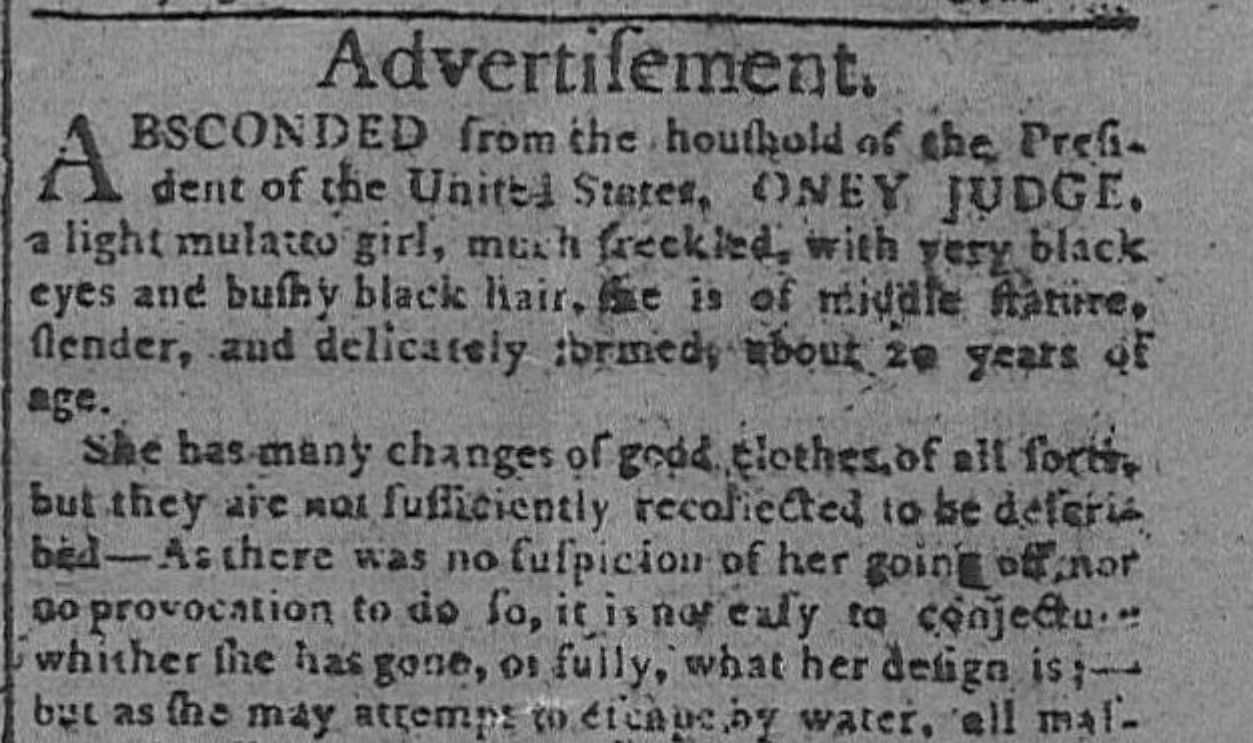

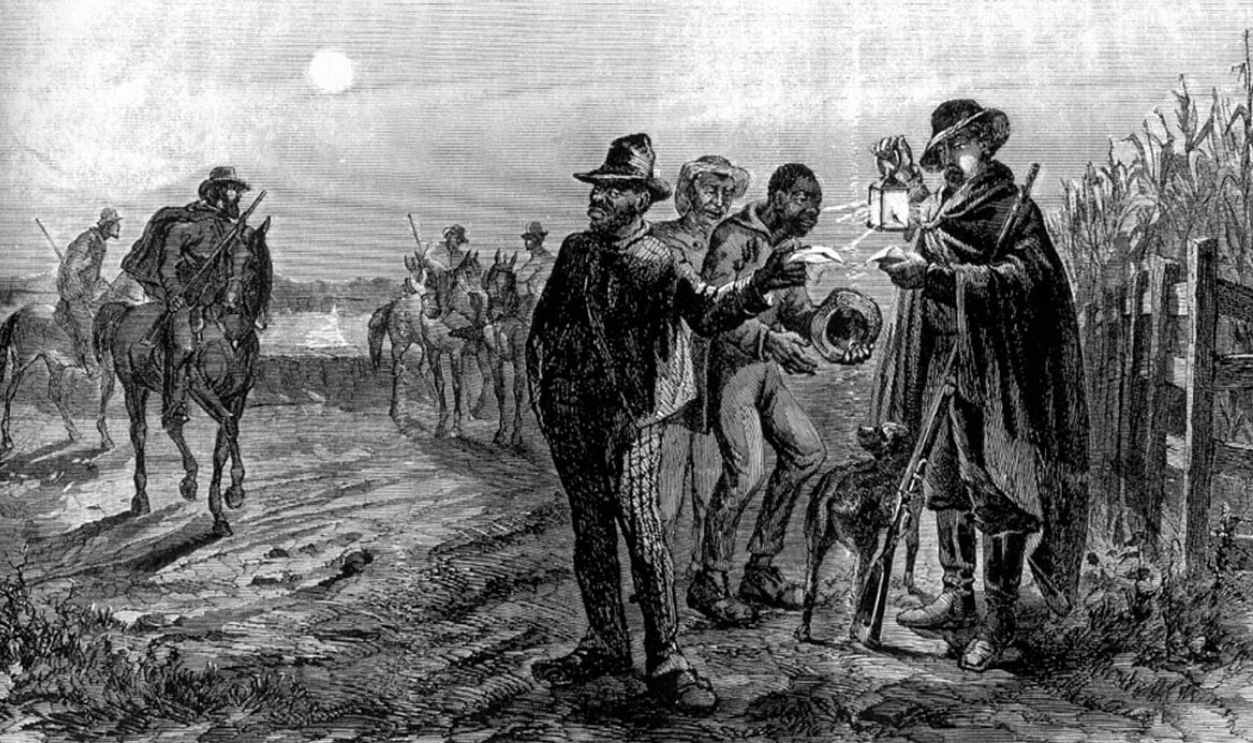

Escape Attempts

Between 1760 and 1799, 47 people managed to escape from Mount Vernon. A key moment happened in 1781 when 17 of them jumped on a British warship. Two of the escapees were Oney Judge—who worked as a seamstress—and Hercules Posey, the cook.

Frederick Kitt, steward of the President's House, Wikimedia Commons

Frederick Kitt, steward of the President's House, Wikimedia Commons

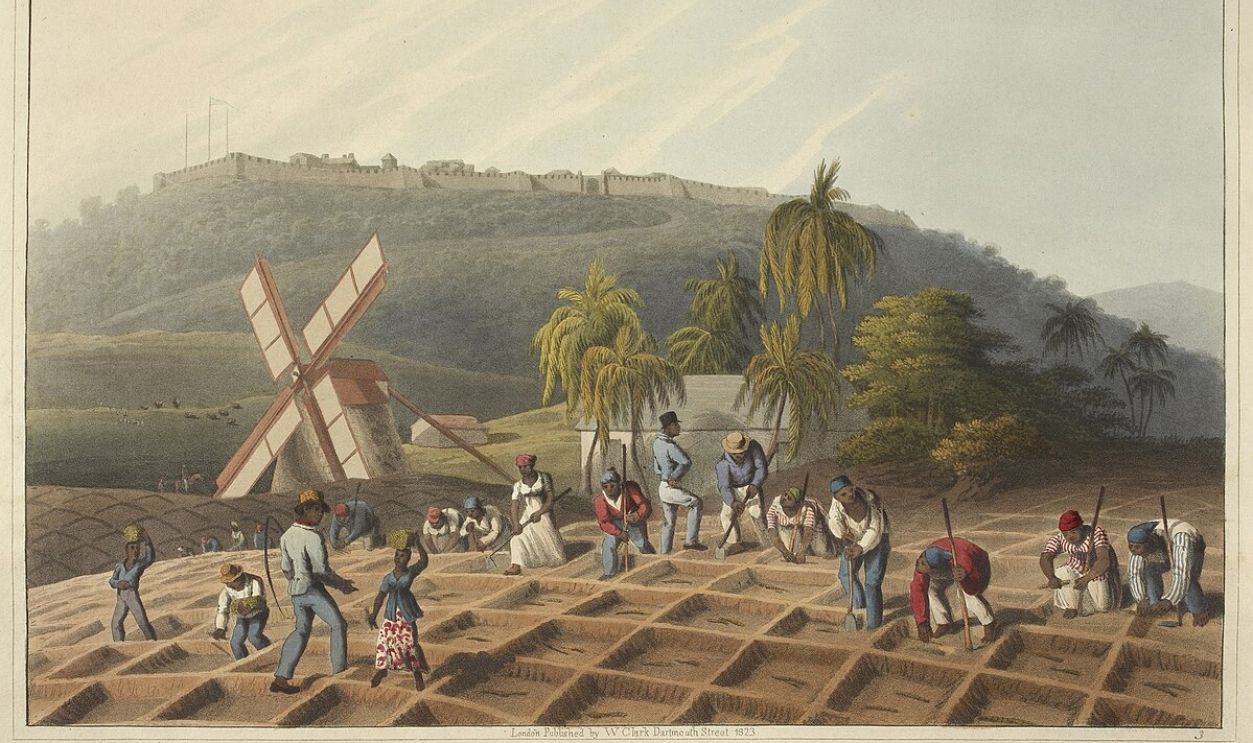

Severe Consequences

Whenever Washington caught any escaped workers, he dealt with them aggressively. In one case, three recaptured individuals were sold to the West Indies as punishment. This was more like a death sentence, given the harsh conditions there. He wanted to show them that running away wasn’t an option.

William Clark, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

William Clark, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Reward System

Slaveowners would implement a dual approach of rewards and punishments. They would do this by offering better blankets, clothing, and occasional cash payments for good behavior. Sometimes, Washington preferred “admonition and advice” over physical correction to encourage productivity.

Frederic B. Schell, Wikimedia Commons

Frederic B. Schell, Wikimedia Commons

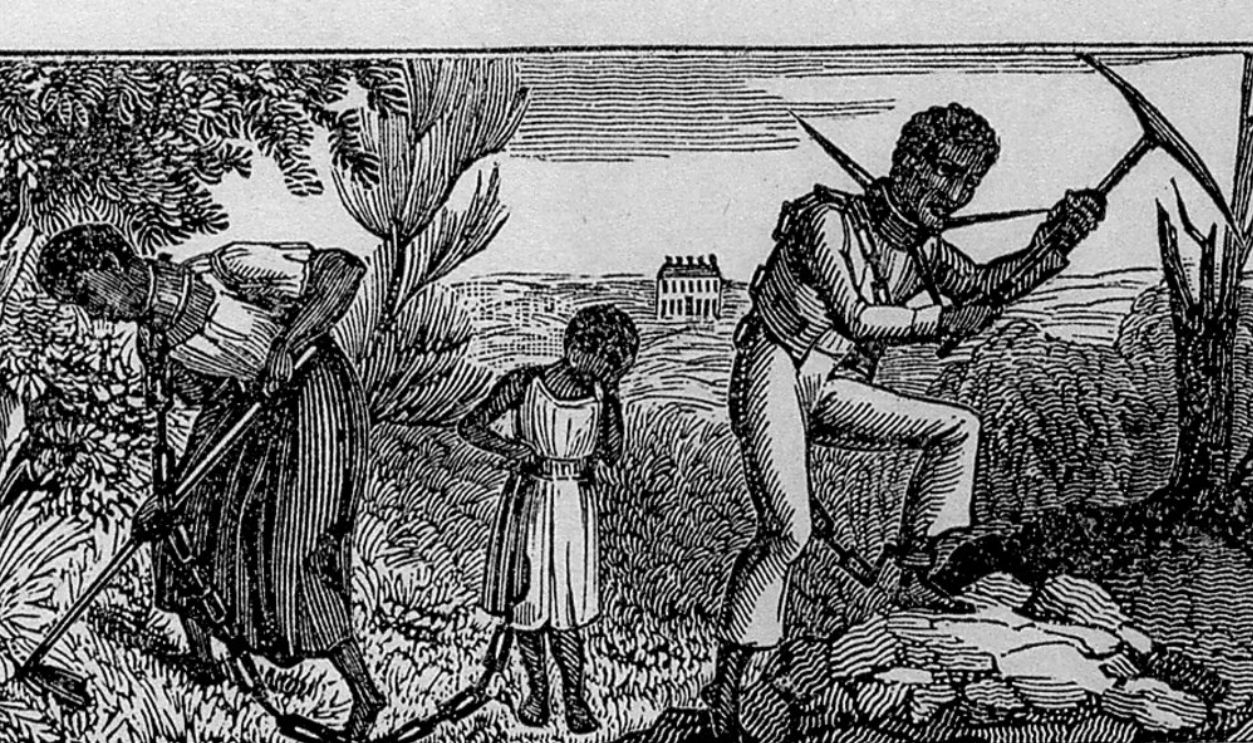

Physical Punishment

Washington didn’t like whipping people, but he did allow it when there was no other choice. You can find a few cases of carpenters getting whipped in 1758. Jemmy faced it in 1773 for stealing, while Charlotte got whipped in 1793 for not following orders.

American anti-slavery almanac, Wikimedia Commons

American anti-slavery almanac, Wikimedia Commons

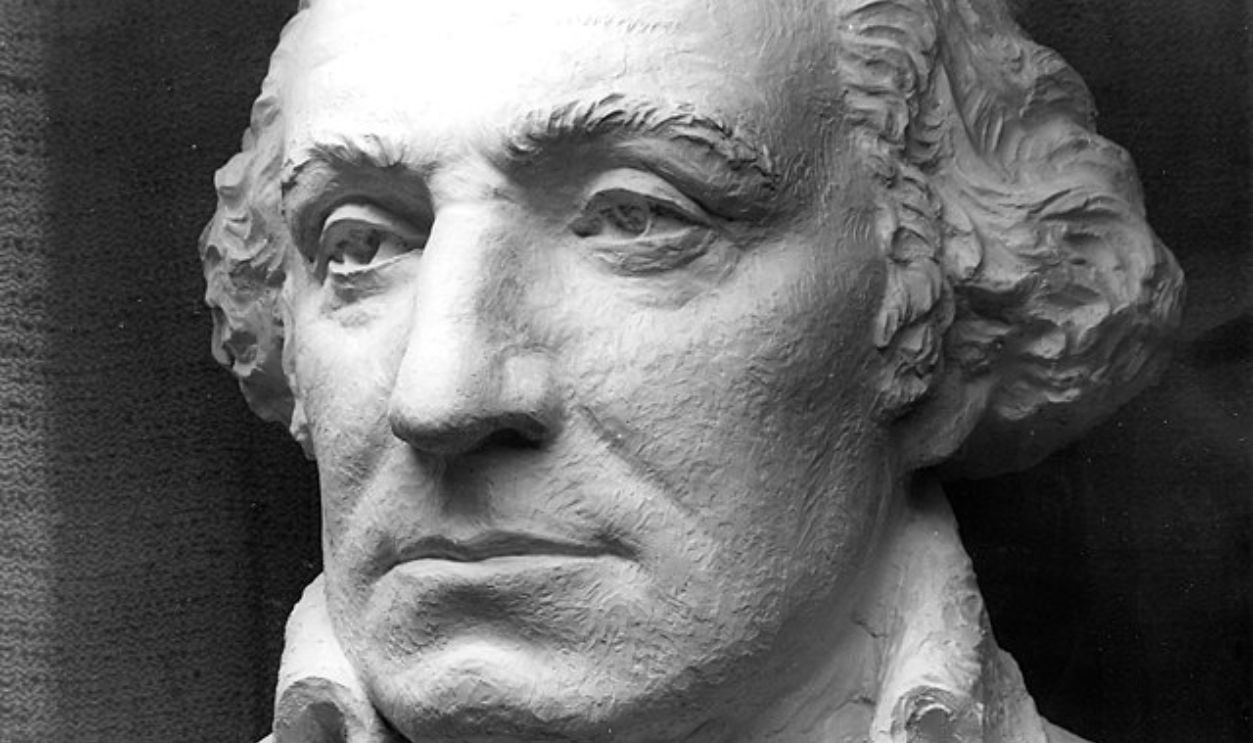

Private Temperament

Though publicly composed, it is said that he displayed a different side in private. Witnesses reported Washington’s violent temper toward servants, who learned to read his moods through his eyes. He used threats of demotion, physical punishment, or being sold to the West Indies.

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Early Perspective

Like other Virginia planters, Washington initially viewed slavery as just normal business. He used to call enslaved people “a species of property”. Then, his first doubts slowly came from economic issues when he switched from tobacco to grain farming in 1766.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Family Separation Debate

Washington took part in a slave lottery in 1769, and families were allegedly split up during the raffles. Wiencek thinks this was a big moment that changed Washington’s views on morality, while others, like Morgan, believe he was mostly focused on business.

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Fairfax Resolves

In 1774, owner Washington spoke out against the slave trade when he signed the Fairfax Resolves. He called it a “wicked, cruel, and unnatural trade”. This was the first time he publicly took a stand against anything related to slavery.

Popular Graphic Arts, Wikimedia Commons

Popular Graphic Arts, Wikimedia Commons

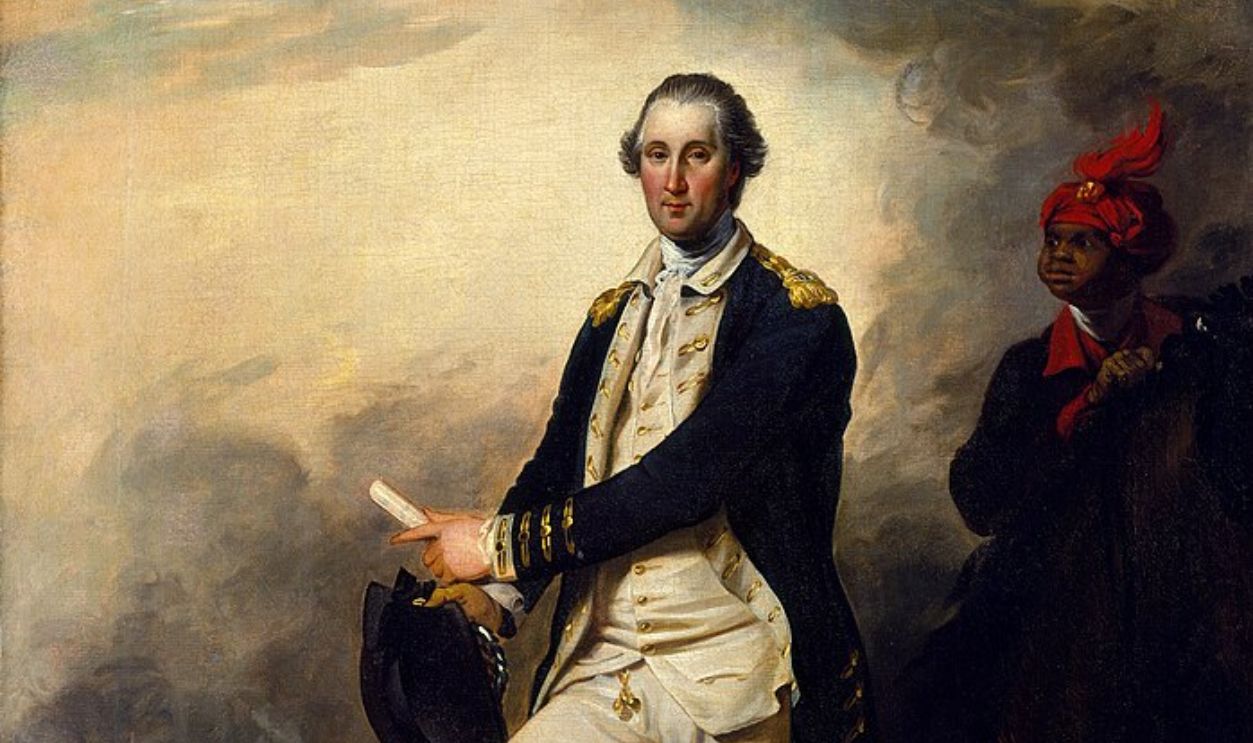

Revolutionary Paradox

During the fight for independence, Washington compared British rule to being enslaved with the use of slavery metaphors. British writer Samuel Johnson pointed out the irony of this situation, asking how people who owned slaves could ask for freedom while denying it to others.

Joshua Reynolds, Wikimedia Commons

Joshua Reynolds, Wikimedia Commons

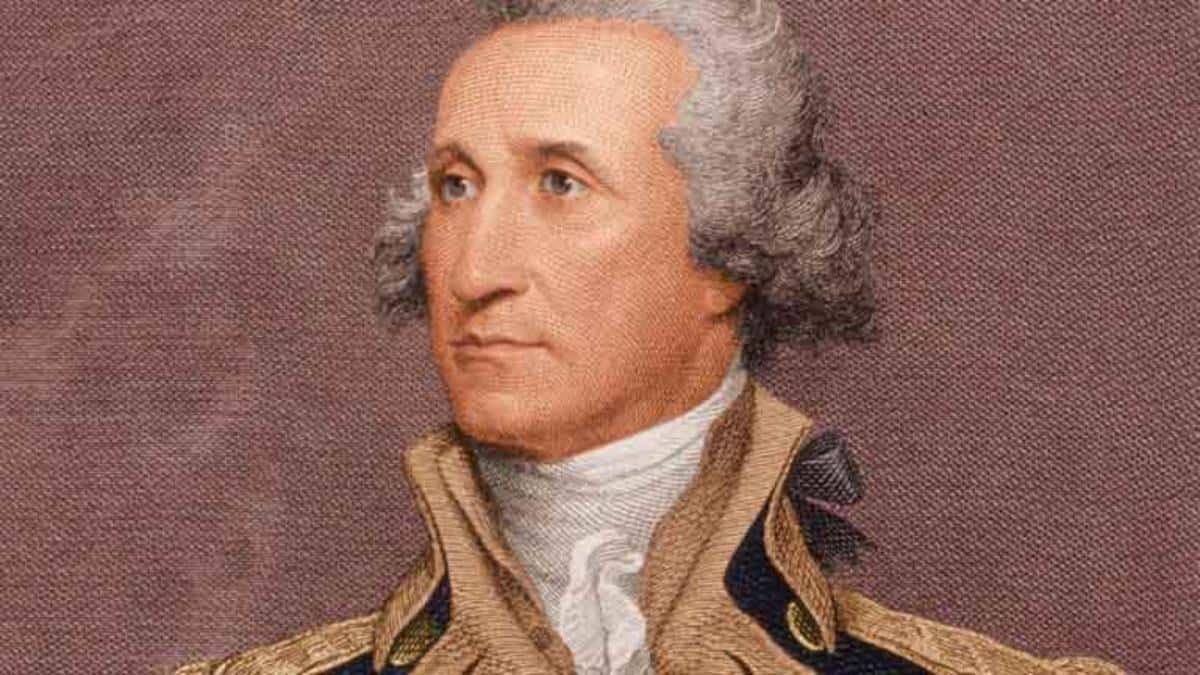

Wartime Perspective

During 1778–1779, Washington expressed a desire to get rid of the Black captives but refused public sales in order to avoid separating families. Still, his motivation appeared mainly economic rather than moral. He still looked at enslaved people as property.

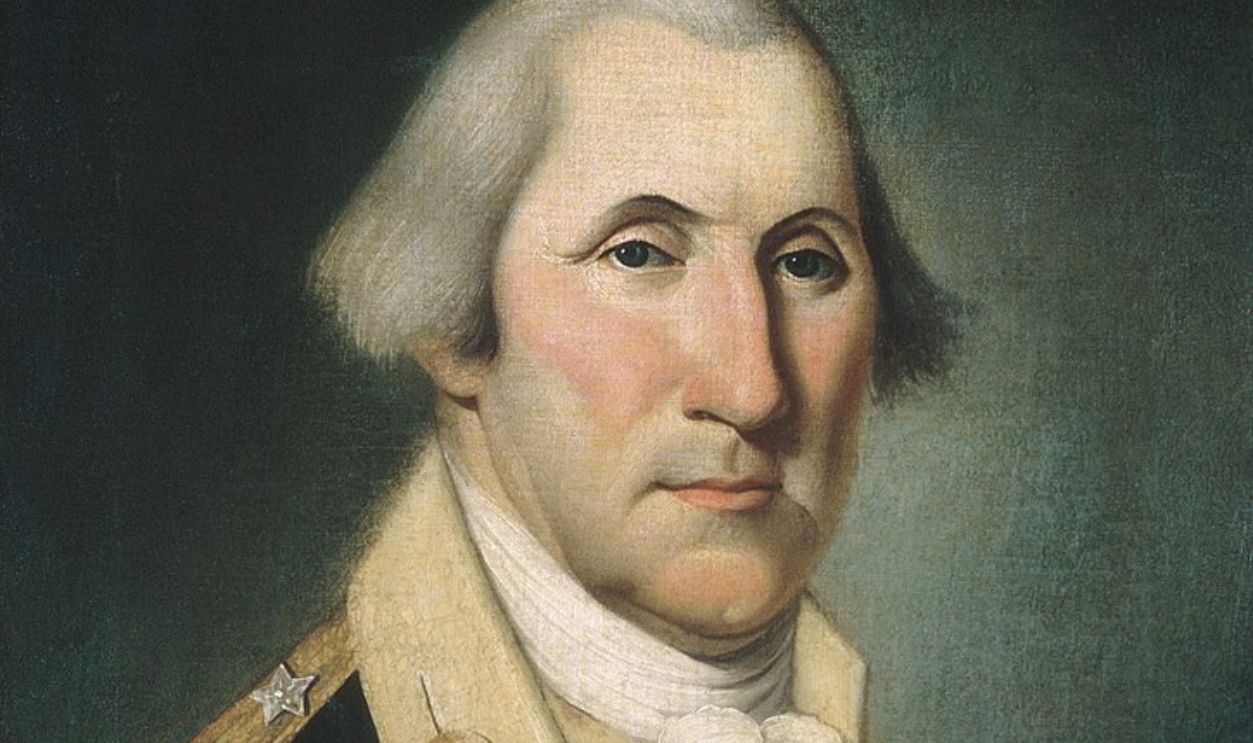

Charles Peale Polk, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Peale Polk, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Gradual Emancipation Stance

After Virginia’s 1782 law eased manumission (slave release), George Washington supported legislative abolition. He privately favored emancipation but believed that slaves needed education on the responsibilities of liberty before being freed. He pushed for a careful way to handle freedom.

Noël Le Mire, Wikimedia Commons

Noël Le Mire, Wikimedia Commons

Private Vs. Public Position

Even though Washington had private conversations with Lafayette and Robert Morris, who were all for abolishing slavery, he was careful about what he said in public. He decided not to jump into Virginia’s abolitionist movement because he was worried about the political fallout.

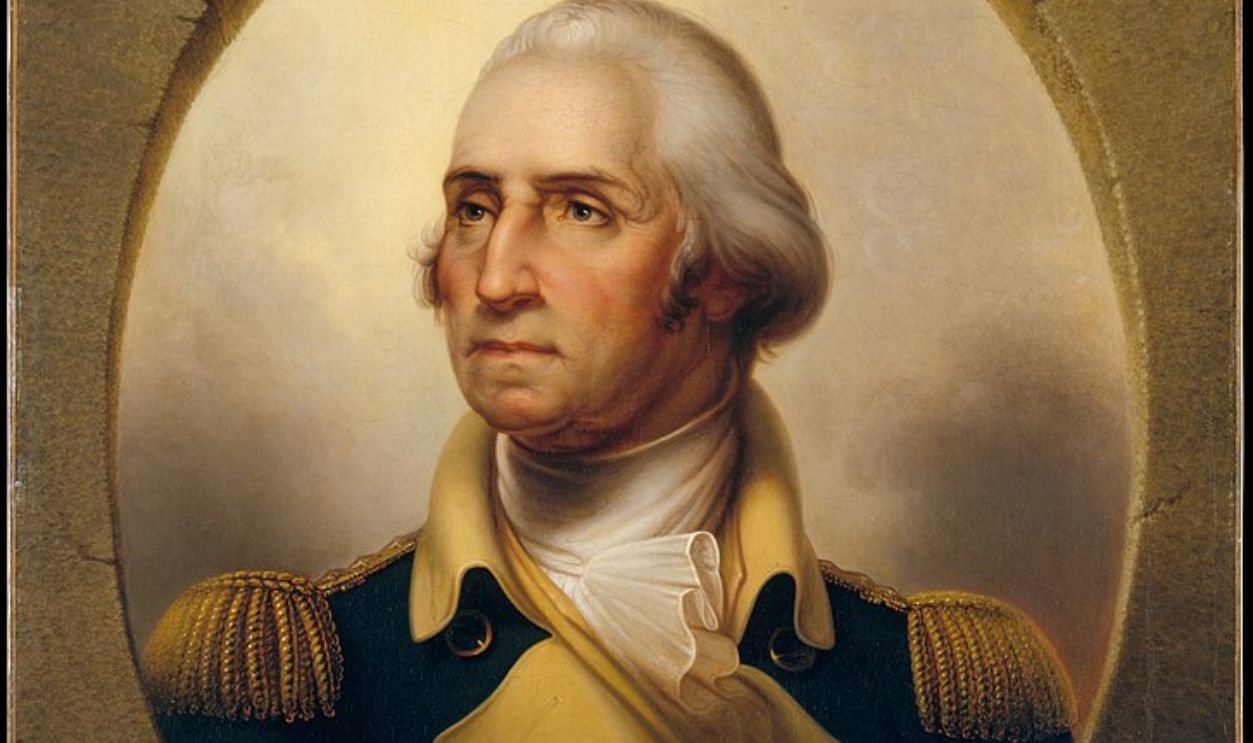

Charles Willson Peale, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Willson Peale, Wikimedia Commons

Constitutional Convention

It was then at the 1787 Constitutional Convention that George Washington presided over compromises on slavery, including the Three-Fifths Compromise and Fugitive Slave Clause. These agreements aimed to protect slavery and assure southern states’ support for the Constitution.

Junius Brutus Stearns, Wikimedia Commons

Junius Brutus Stearns, Wikimedia Commons

Presidential Actions

During his time as President from 1789 to 1797, Washington took actions that both supported and limited slavery. He approved the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which made it possible to capture escaped slaves, but he also signed laws that banned slavery in the Northwest Territories.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Philadelphia Servants

To get around Pennsylvania’s gradual emancipation law, which freed slaves after six months of living there, Washington would switch his enslaved workers back and forth between Mount Vernon and Philadelphia. But, he kept this under wraps to avoid causing any issues.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Economic Burden

Around 1787, Washington had racked up a bit of debt in Virginia. He was struggling with low crop yields, the costs of keeping up his estate, and the challenge of taking care of unproductive slaves. All of this together put a real strain on his finances.

Mathieu Landretti, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mathieu Landretti, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Unrealized Emancipation Plans

Around the 1790s, he made plans to free his slaves by selling western lands and leasing farms. Even though he felt strongly against owning slaves, the plans didn’t work out because the land was too expensive, and there were issues with Martha Washington’s dower slaves.

Roman Tokman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Roman Tokman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Immediate Aftermath

Martha Washington decided to free her husband’s slaves in 1801. She felt uneasy about having them around. Most of them left Mount Vernon quickly, but five free women and William Lee stayed behind. The other dower slaves continued to be enslaved by the Custis heirs.

John Trumbull, Wikimedia Commons

John Trumbull, Wikimedia Commons

The 1799 Will

Washington’s will, written 5 months before his death, was about his enslaved workers. He freed William Lee and set 123 others free after Martha died. He mandated care for the elderly and education for children and also prohibited the selling of slaves out of Virginia.

Rembrandt Peale, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Rembrandt Peale, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Mixed Outcomes

The former slaves had different experiences. Some did well for themselves and even set up Free Town in Fairfax County by 1812. Others, though, faced challenges because of prejudiced laws and social obstacles. Oney Judge said she’d take freedom over slavery any day.

Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, Wikimedia Commons

Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, Wikimedia Commons

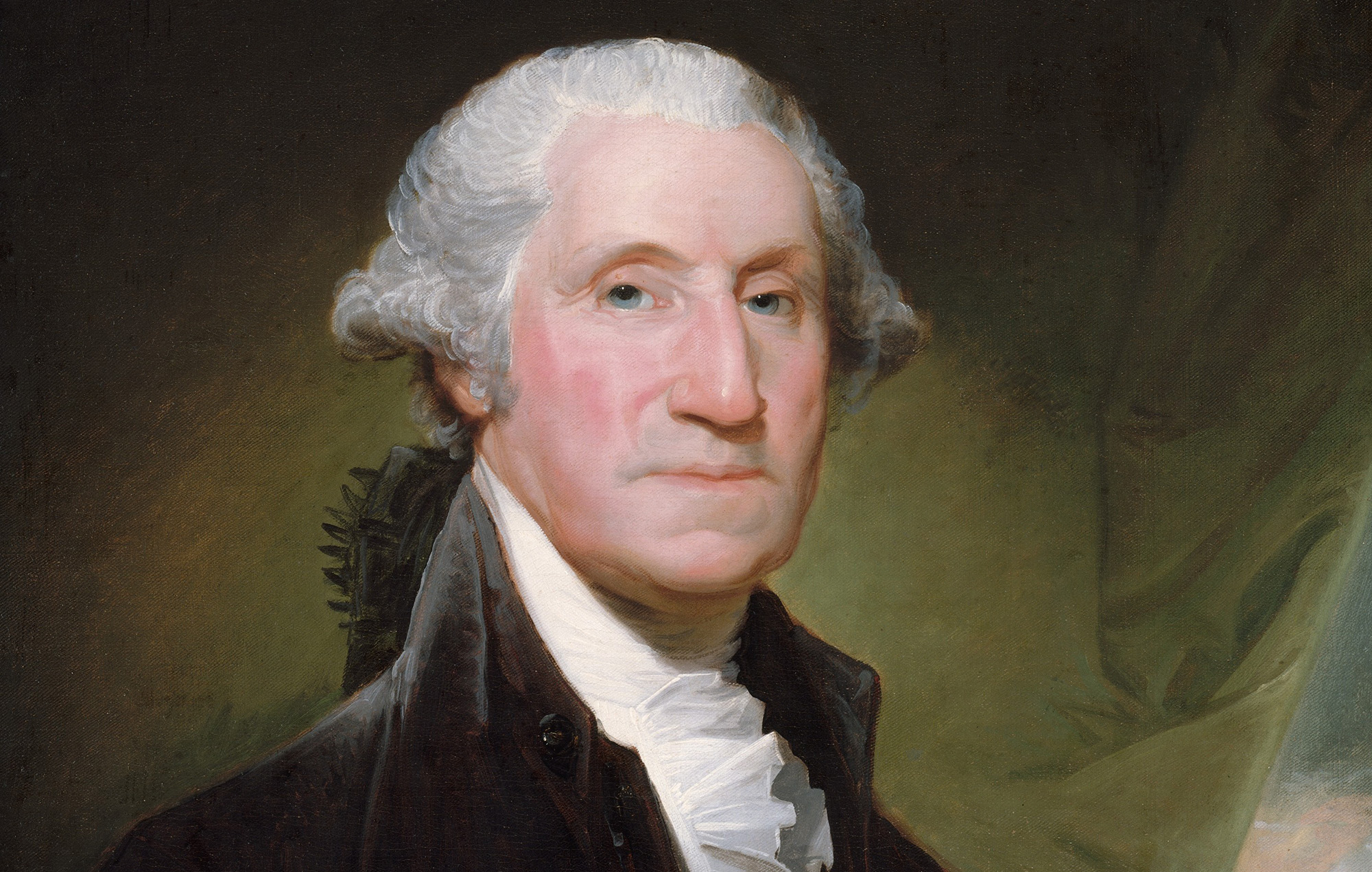

Competing Narratives

Washington’s will turned into a big deal, with different groups seeing it in their own way. Antislavery supporters looked at him as someone who was ahead of his time in wanting to end slavery, while pro-slavery folks focused on his role as a caring slave owner.

Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

Initial Recognition

In 1929, Mount Vernon put up a small plaque by Washington’s crypt to recognize the unmarked graves of enslaved people. It called them “faithful colored servants”. For a long time, this spot didn’t grab much attention in tourist guides and materials.

Sarah Stierch, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sarah Stierch, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Memorial

Then, in 1983, The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association placed a memorial that clearly acknowledged the “slaves at Mount Vernon”. Since 1985, archaeological digs have uncovered more than 130 burial sites, giving us a better picture of the lives of the enslaved community.

Sarah Stierch, Wikimedia Commons

Sarah Stierch, Wikimedia Commons