For centuries, men dominated science, technology, engineering, and math (now known as STEM)--but that doesn't mean that women didn't make scientific history too. Did you ever wonder where the basis of Einstein's theory of relativity came from? Einstein himself credits a woman, Emmy Noether. Are you grateful for the wi-fi that lets you read Factinate? Thank Hedy Lamarr, Hollywood screen siren by day and secret tech innovator by night.

Noether and Lamarr, alongside well-known figures like the physicist and chemist Marie Curie, the astronaut Sally Ride, and the mathematician Katherine Johnson, whose incredible life was recently made into the movie Hidden Figures, are just some of the many amazing women who made scientific history.

Overcoming gender and race-based discrimination, lack of access to education and jobs, and disbelief about the credibility of their extraordinary findings, women in science are true (s)heroes. So, get out your calculator, prep your beaker, and sterilize your medical instruments: here are some brilliant facts about the fiercest women scientists.

1. The Tragic Chemist

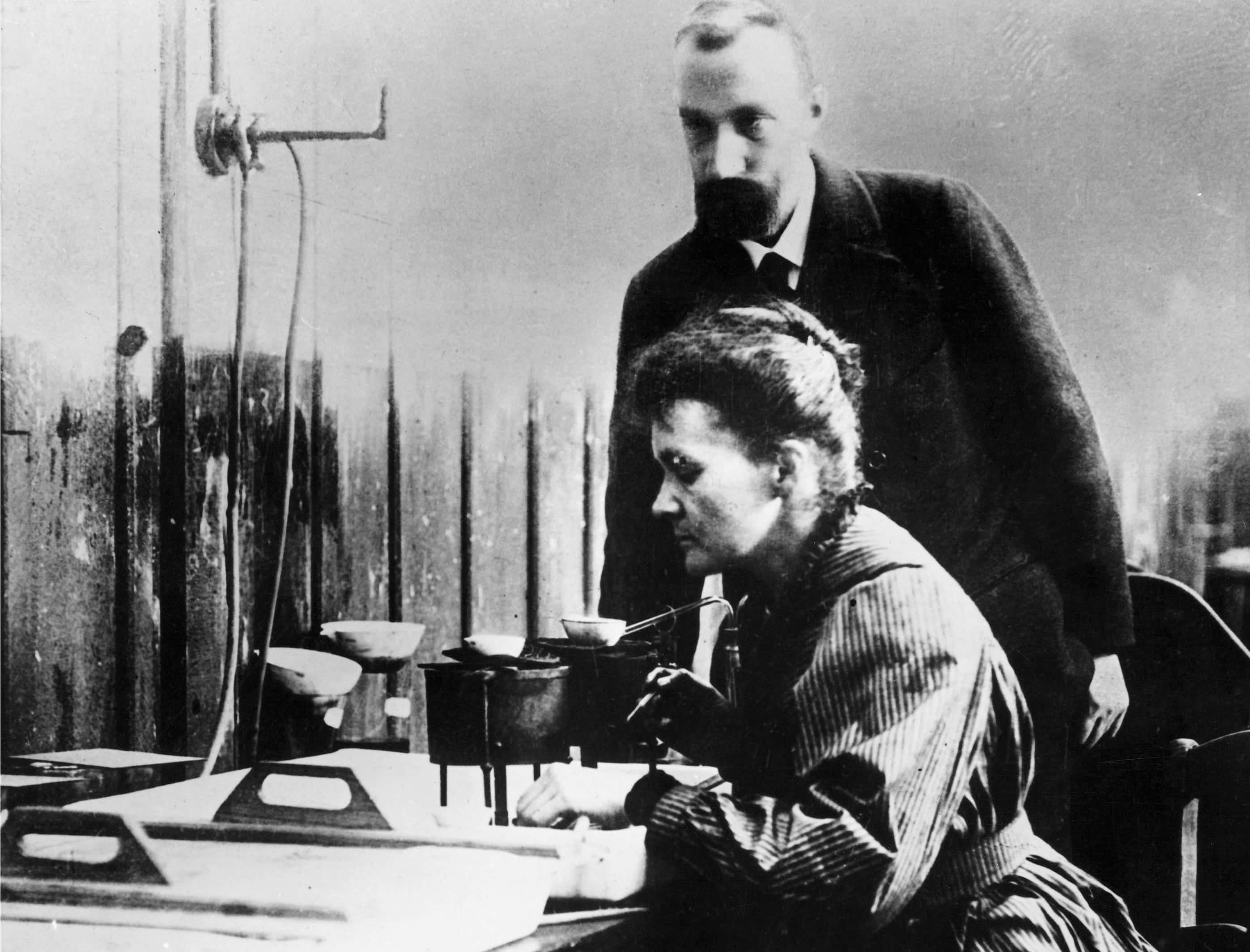

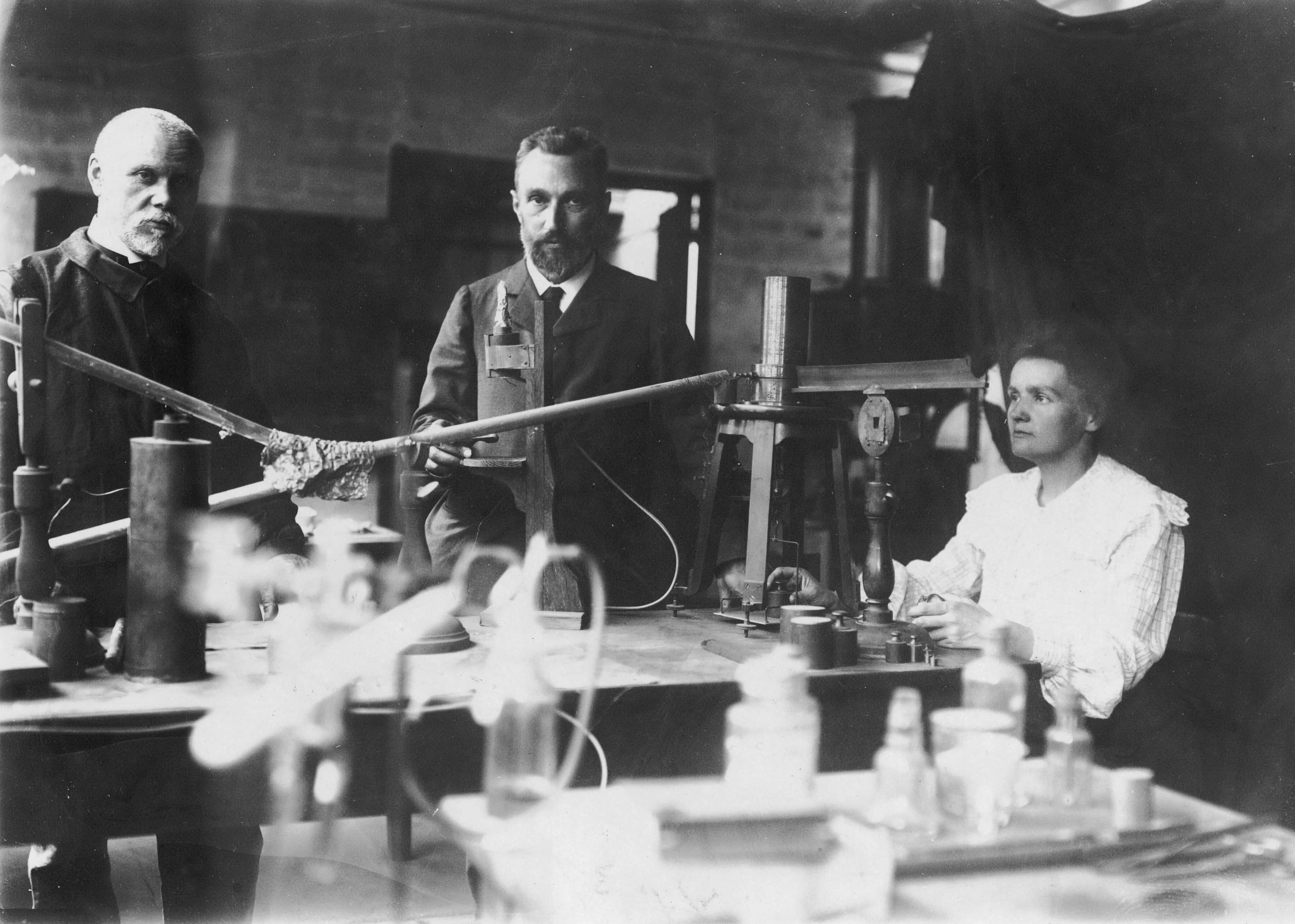

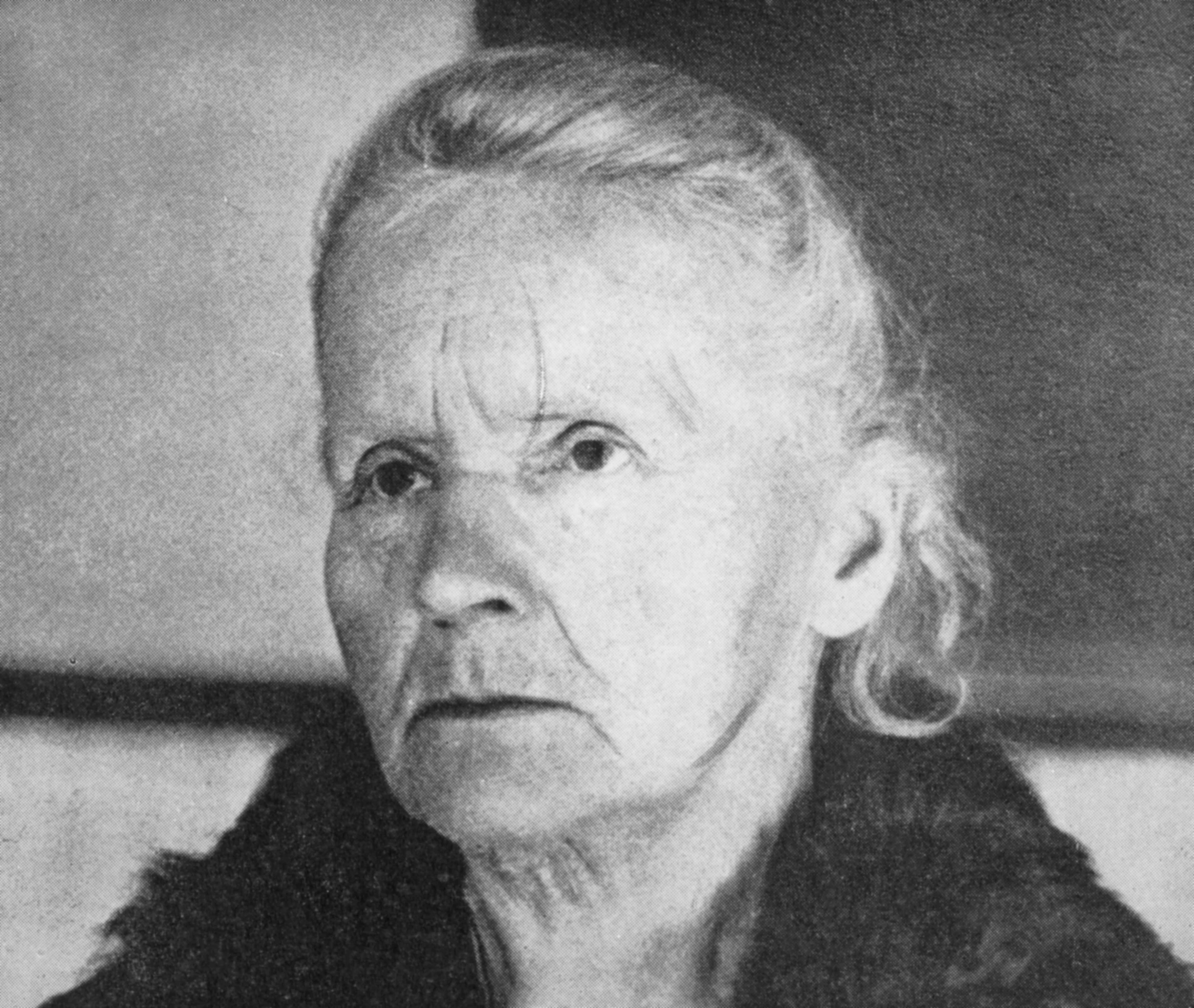

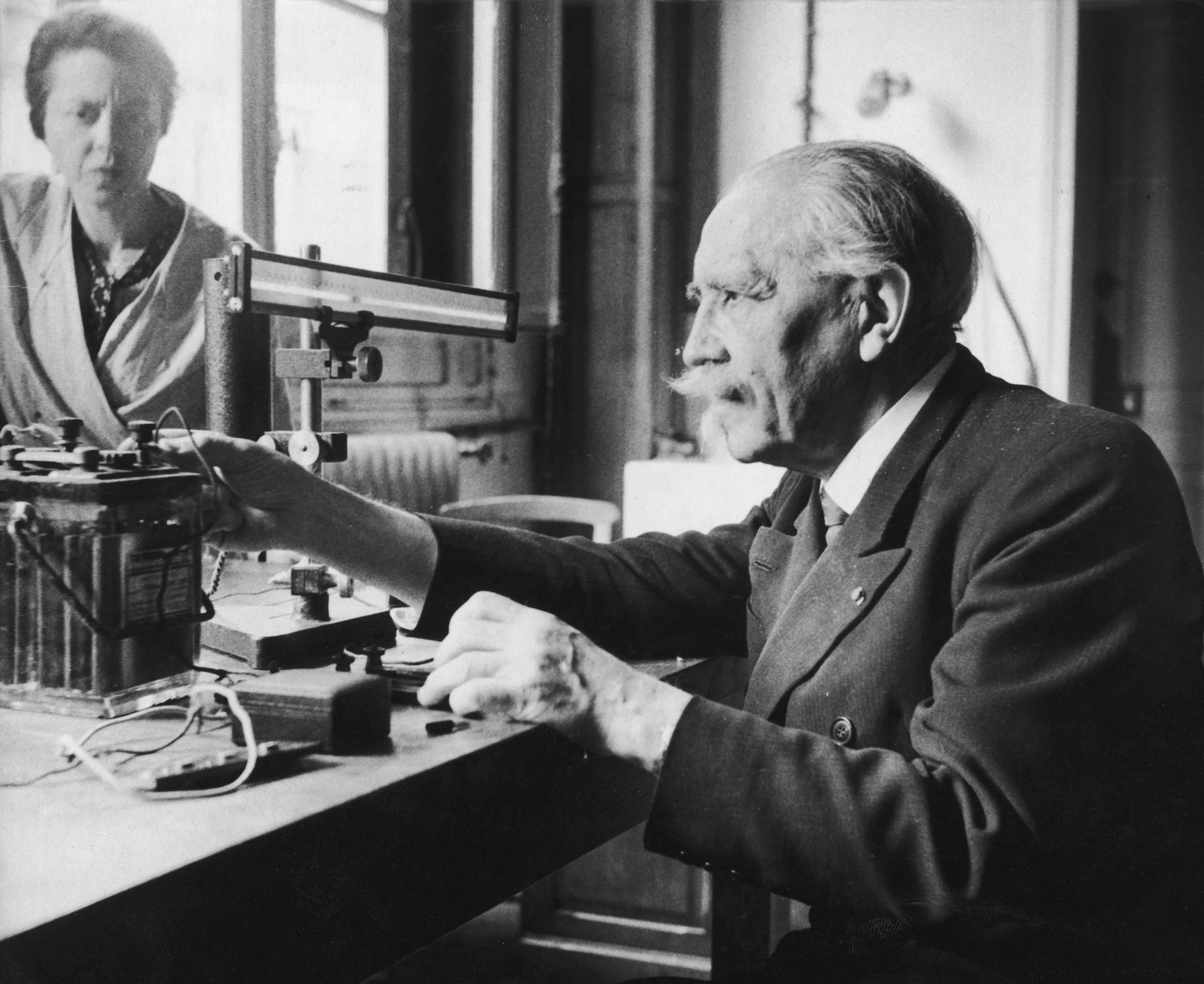

Marie Curie requires little introduction. The trailblazing scientist formed one-half of the Curie power couple, who went on to win the Nobel Prize for discovering radium. But Marie didn’t stop there: in her widowhood, Curie won another Nobel prize, cementing herself in history as a role model for women in science.

Behind her scientific honors, however, lay a profound historical struggle. Marie's path to knowledge was fraught with starvation, sexism, armed conflict, love, and, yes, the occasional bedroom scandal. Raised in a time when higher education for women was not just taboo but often against the law, no one can accuse Marie Curie of enjoying an easy walk to the podium.

2. Running out of Faith

For a time, Marie Curie grew up in a multifaith Polish household: her mother Bronisława was a devout Catholic, while her father Wladyslaw Skłodowski was an atheist. After the heartbreaking sudden demise of both her mother and oldest sibling Zofia from illnesses, everything changed for Marie. The future scientist gave up her mother’s religion and turned towards agnosticism.

3. Science vs. Severance Package

Curie’s father turned to desperate measures when the Russian government shut down labs in Polish schools. He actually took lab equipment from his teaching job so that he could teach his children about science in secret. Eventually the school fired Mr. Curie for his radical political views. The family operated a boarding house to make ends meet. Anything for science in the Curie household!

4. Speak No Evil, Take No Offense

When the Royal Institution in London invited Marie and her husband to give a lecture on radioactivity, the Curies were delighted. But when Marie showed up to the 1903 speech, she realized the chilling truth. Women weren't actually allowed to speak at the Institution. Pierre did all the talking. Beware, reader, this is not the first time you'll encounter gender-based discrimination on this list.

5. Starving Scholar

School in Paris was not as charming as it sounds. As Marie studied physics, chemistry, and math at the University of Paris in 1891, she was so poor that she often fainted from hunger. Learning by day, tutoring by night, Marie barely made it out alive. She finally won her degree in physics in 1893.

6. In the Wings of Knowledge

While it wasn’t financially easy for Marie and her sister to get an education, it was also legally dangerous. At the time, higher learning for women was actually against the law in Poland, so it goes without saying that the University of Warsaw didn’t accept ladies. Instead, Marie and Bronisława got their scholastic head start in an underground women’s institution called the “Flying University”—so named because it was ‘fly by night’ and always changing locations to outrun the law.

7. Beat That

Most people remember Marie Curie as the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in 1903—a physics award that she shared with her husband, Pierre, for their work on radioactivity. Fewer people know that Curie actually won again for chemistry in 1911. To this day, Curie remains the only person ever to win two Nobel Prizes in separate science categories. Dang.

8. Welcome to the Love Shack

Marie and her husband partly completed their prize-winning experiments in an old shed behind a school. The old labs at work just couldn’t house all the equipment that the Curies required to break down ore. The shack was....not great. It was not well ventilated and the roof leaked frequently. One visitor described the shed as "a cross between a stable and a potato shed". Hey, one person’s creepy potato hut is another science couple’s genius love shack.

9. The Silent Struggle

After her mother’s passing, Marie Curie experienced long struggles with mental illness. Although she graduated from a gymnasium school (a type of school with a strong emphasis on academic learning) with a gold medal in 1883, she collapsed from possible depression soon after and had to take a “gap year” of sorts.

10. Travel-Sized Trauma

As tech gets more advanced, it also tends to get smaller (have you ever seen a picture of an early computer? They took up entire rooms!). Interested in advancing her work on radium, Curie invented mini X-ray machines. She wanted to assist French troopers during WWI, and did so with style. Not only did she create the technology, she also learned to drive and helped wounded men herself at the Battle of Marne. The small X-rays became known as “petite Curies".

Wikipedia, vapaa tietosanakirja

Wikipedia, vapaa tietosanakirja

11. Do Not Try This At Home

At the time of their investigations, Marie and Pierre Curie had no idea that radium was so hazardous to human health. (To be fair, they literally just discovered it). But their scientific brilliance had horrific side effects. Because Curie didn't know radium was dangerous, she literally walked around with bottles of the harmful substance in her pockets. At night, the couple basked in the whimsical, radioactive glow of their lab. Heck, Curie even used radium as a night light. Guys, do not do this.

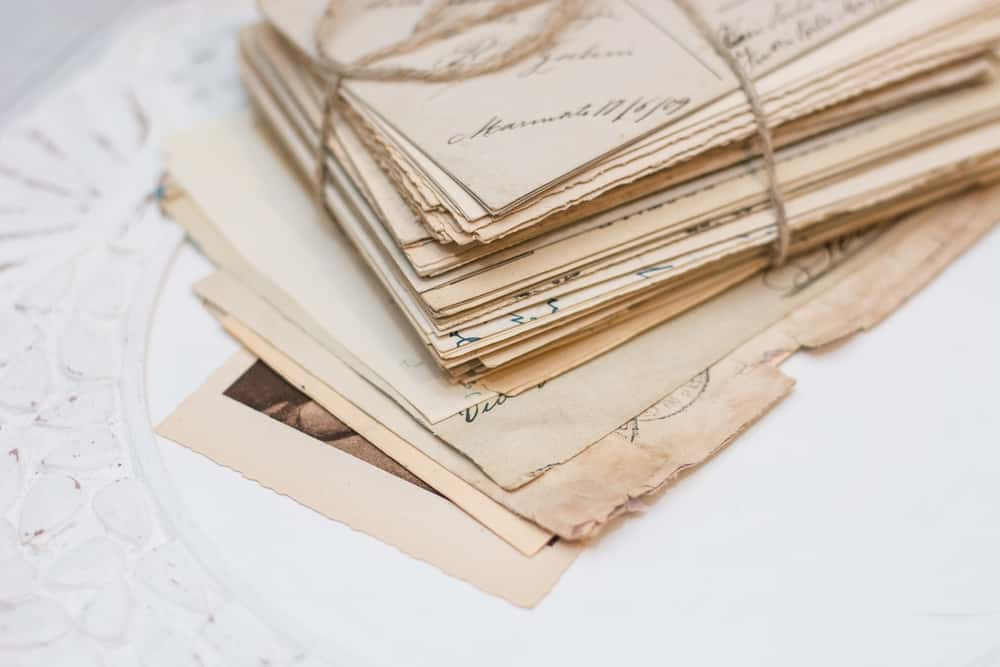

Because of this longterm exposure, Curie's notebooks are still too radioactive to touch. It'll take 1500 years for them to become safe again. More tragically (and better known), Curie's familiarity with radium was both her greatest achievement and her final undoing. She succumbed to aplastic anemia, brought on by radium exposure, in 1934.

12. The People’s Element

Curie's legacy, however, lives on. A real one, she refused to claim intellectual property over her discovery of radium. Instead, she and Pierre made their research open to other scholars and producers. Even during the “Radium Boom” of the 1920s—when a single gram cost $100,000—Marie had zero regrets about her open-access approach to science. In her words, “Radium is an element, it belongs to the people". Preach, Marie.

13. Double Standards

Marie Curie lived life on the edge. From her scientific experiments to her bombastic personal life, no one could rein her in. In 1910 and 1911, Marie started an affair with Paul Langevin, a former student of her late husband. Unfortunately, Langevin was married (but estranged from his wife), so the media lambasted Marie as a homewrecker. Anti-Semitic tabloids even presented her as a foreign Jewish temptress.

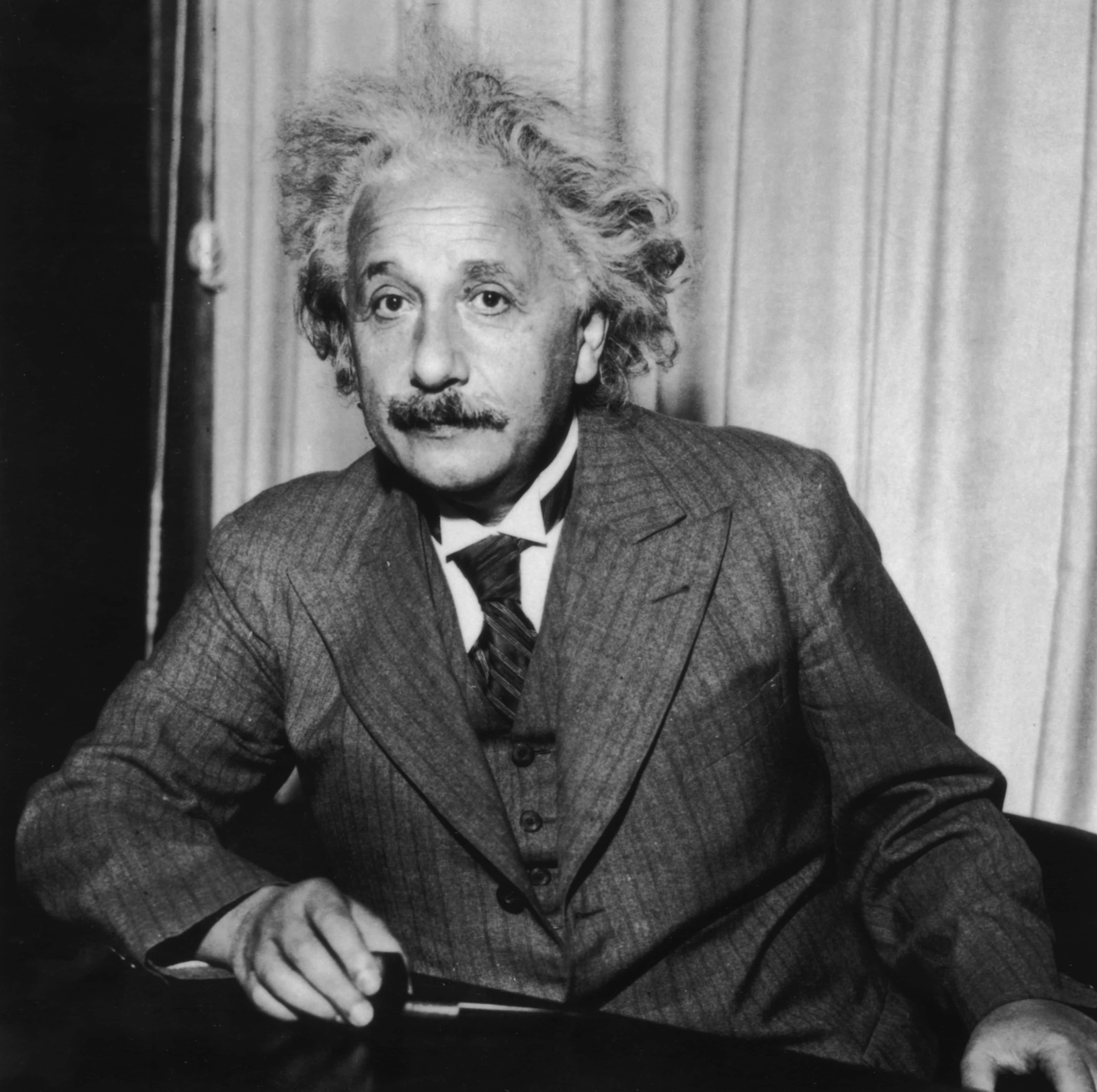

14. Thanks, Einstein

The female scientist was at her lowest emotional point when Albert Einstein wrote her a very special letter. In his note, Einstein told Curie how much he admired her achievements. He also offered some good PR advice. Einstein told Curie not to “read that hogwash, but rather leave it to the reptile for whom it has been fabricated". Einstein's advice did the trick. Curie brushed off the scandal and accepted her second Nobel Prize in Stockholm, like a boss.

Bonus Fact: Albert Einstein and Marie Curie were close friends for almost 25 years. In addition to attending those fancy smart people events, the pals also just liked to have fun and take their families together for hikes on the Swiss Alps. I want to see that road trip movie. Imagine the "Take my money" gif here, reader.

15. Maybe In Another Life, Marie Curie…

Long after Marie Curie ended her affair with Paul Langevin, her granddaughter and his grandson put things right. Even though their grandparents couldn't make it work, they could. Yup, the descendants tied the knot. And like their famous ancestors, Curie's granddaughter and Langevin's grandson were also scientists, nuclear physicists specifically. Nerd love forever.

16. Nerd Love

While Marie adored her husband Pierre, she enjoyed a powerful connection with another suitor. In her youth, Marie became star-crossed lovers with the future acclaimed mathematician, Kazimierz Zorawski. At the time, Marie worked as a governess in his parents’ household, leading the duo to enter a scandalous inter-class romance.

While Marie and Kazimierz discussed marriage, Marie was too poor to be a good prospect for his family. The affair ended, with mutual pain. Even after Zorawski became an esteemed professor at Warsaw Polytechnic, Marie’s now-elderly sweetheart would seat himself in front of her statue at the Radium Institution and stare wistfully. I'm not crying, it's just raining on my face.

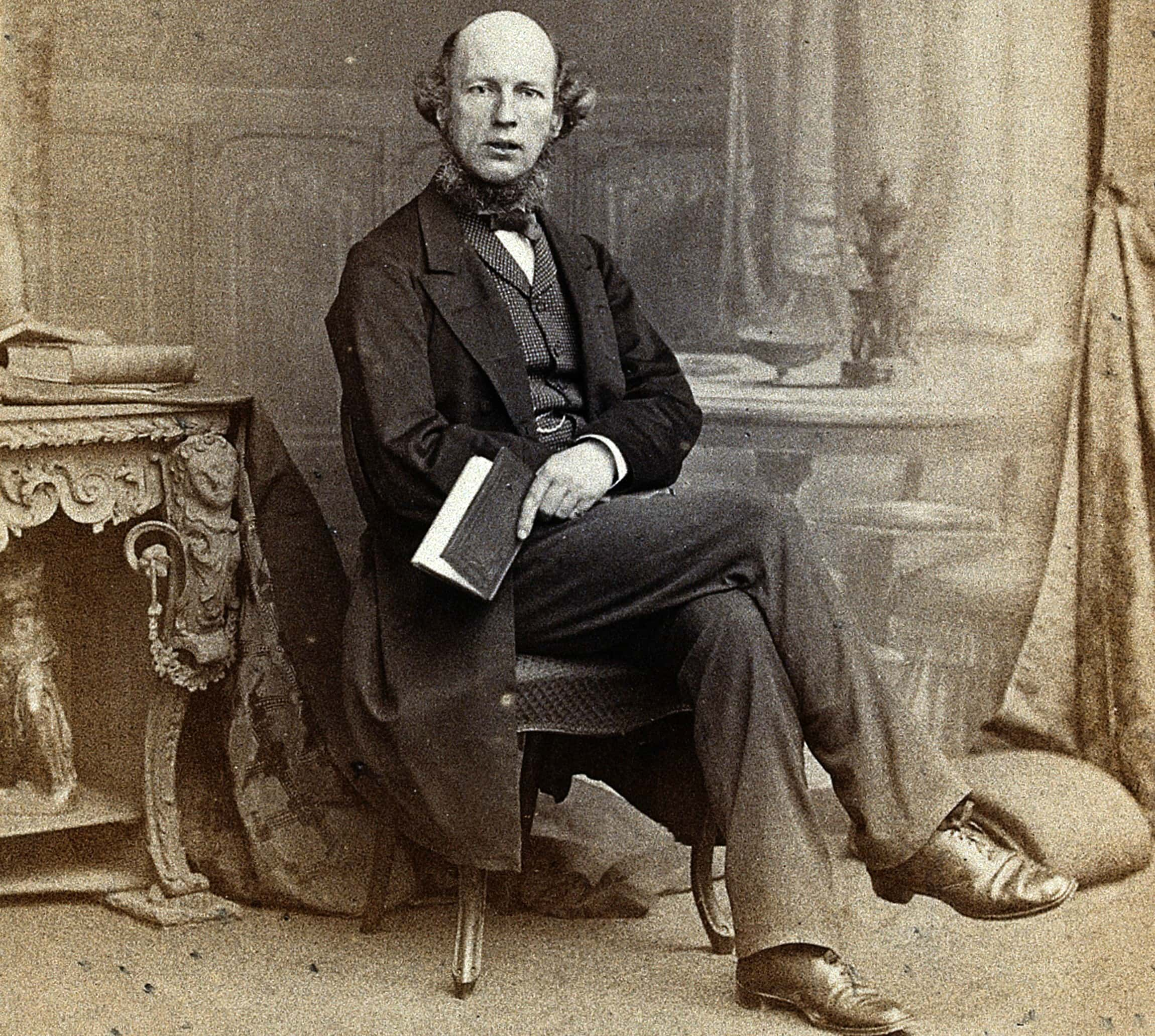

17. The Enchantress of Numbers

Ada Lovelace is a 19th-century aristocrat who also just so happens to be one of history's first computer programmers. However, this gentlewoman genius came from a troubled lineage. As the daughter of the infamous Lord Byron, she entered scandal at the moment of her conception. Like Marie Curie, Lovelace struggled with dramatic life events, including scandalous affairs and gambling debts, even as she innovated computer programming.

18. Four Is a Crowd

What exactly is so bad about Lord Byron being your dad? Well, let's just say that he and Ada didn't get off to a good start. When Ada was just a few weeks old, Byron tried to evict his infant daughter for an utterly chilling reason. Using his legendary way with words, Byron told his wife Lady Annabella Byron that she and their daughter needed to leave ASAP. Sorry, ladies, but Byron has better things to do, like pursue a beautiful actress. After all, it’s hard to get stage stars “in the mood” with your wife and crying baby in the house.

19. Who’s Your Daddy?

But in the end, Byron left. He peaced out of England mere months after Lovelace's birth and passed on when she was eight. Father and daughter barely knew each other. At the very least, Byron seemed to regret his profoundly bad parenting. Mere moments before his passing at the young age of 36, he allegedly cried out, “Oh, my poor dear child!—my dear Ada! My God, could I have seen her! Give her my blessing".

Despite his apparent sorrow, Lovelace's mom wasn't impressed. She didn't show Ada a picture of her father until Ada was 20 years old. All things considered, can you blame her?

20. Count Your Way to Mental Health

Lovelace owes her robust education in science and math to her own math prodigy mother, Lady Annabella Bryon. Oh, and the fact that her mother was horribly afraid of Ada inheriting her poetic father’s “insanity". Lady Annabella figured that honest, non-romantic pursuits would keep her daughter on the straight and narrow. I guess this meant math, the least sexy subject known to humanity.

21. A Picture Says a Thousand Numbers

Evidently, Lady Annabella's distinctive parenting strategy paid off. Scholars now credit Lovelace with the first published algorithm ever programmed specifically for an early computer. Lovelace translated an Italian article that described Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine, but because her extensive appended notes were three times longer than the actual article, Lovelace went down in history as the world’s first computer programmer.

In regular people terms, you can thank Lovelace for reaction gifs. She was one of the first people to consider that computers could do more than just crunch numbers. In her mind, they might also digest writing, music, pictures, and even sound. Looks like dad's poetic side got into Lovelace's scientific brain after all...

22. The Family Jewels Are a Small Price to Pay for a Bit of Fun

You’re never too smart for a gambling problem. Lovelace struggled to control herself at the horse tracks and once lost £3,200 pounds (a fortune in her time) on a single race. At one point things got so bad that the computer wiz sold her family diamonds just to keep afloat. At another low point, Lovelace tried to mush her love of losing money with her love of math. She teamed up with a bunch of con artists to develop a “predictor” for horse races. Evidently, it did not work.

23. Down for the Count

Brains don’t always equal brawn. Case in point: Lovelace spent much of her youth sick and disabled. Serious migraines affected her vision, and poor Ada was paralyzed from about age 14 to 16 after a terrible fight with measles. She had to walk with a crutch for years. However, this pain had a surprising bright side.

Because Lovelace struggled to move around freely, she started to study flight. The young scientist wrote a book called Flyology. Her work detailed the anatomy of different kinds of birds in all their varied size and glory.

24. Thanks for the Name Drop

At the age of 20, unconventional Ada made the conventional 19th-century move to marry respectably. In 1835, the young scholar wed William King-Noel, the Earl of Lovelace. He was 10 years her senior. In addition to several really fine manors, Lord Lovelace gave Ada the name by which she would be known to the public for centuries after.

25. She Loves Me Not

Ironically, Lovelace's "moral instructor" once encouraged her to cheat on her husband. In 1843, William Benjamin Carpenter educated Lovelace and her children. Carpenter himself was married, and tried to get Lovelace to at least confess to mutual feelings toward him. He argued that his own marital status would somehow prevent their conduct from being “unbecoming". Nice try, Willie. Lovelace quickly cut things off.

26. Not Quite a Lady

Though she grew up in luxury, Lovelace somehow missed the memo on female decorum. One gossip rag at the time described her as “the most coarse and vulgar woman in England". To be fair, her mad, bad, and dangerous father would have been proud to hear his little girl described so scandalously. On a less exciting note, Lovelace also wasn't the best dresser, despite how awesome she looks in the images below.

27. Burn After Kissing?

For Lovelace, rumors of infidelity were common (players gotta play?). Most notably, Lovelace apparently engaged in inappropriate relations with John Crosse, the son of one of her colleagues. No one knows for sure if they consummated their relationship, but after Lovelace passed on, Crosse destroyed all their correspondence as part of an ambiguous court deal. Adding fuel to the fire, she even bequeathed Crosse all the heirlooms from her father.

28. Opium Haze

But Lovelace hid a terrible secret throughout her adult life. She battled a serious addiction to laudanum (an opium tincture) for her various ailments. If she didn’t have laudanum, she experienced withdrawal symptoms such as extreme stress and itchy eyeballs. As soon as she could have some, the symptoms relaxed, and she went back to normal.

29. Extra Credit

When she was just 18 years old, Lovelace enjoyed a scandalous affair with her tutor, William Turner (Héloïse and Abelard, anybody?). They even schemed to ditch the books and elope together. Unfortunately, her beau’s family recognized the infamous daughter of Lord Byron and squealed to her mom, Lady Byron.

30. The Family that Sticks Together Is Never Surprised

In 1841, Lady Byron informed Ada that she and her "cousin" Medora were actually much, much closer. They were half-siblings. To put it simply (and grossly), Lovelace’s scandalous father maybe had an affair with his own half-sister. Look, I know Byron was interested in everyone, but at least keep it out the family, dude.

By our standards, Lovelace underacted to this gross revelation. She wrote to her mom, “I am not in the least astonished". But...how??

31. Honor Thy Father…in Everything

When confronted with her late father’s alleged affair with his own half-sister (how many times will you read that?), Lovelace blamed one person and one person only: Medora's mother, Augusta Leigh. Lovelace wrote, “I fear she is more inherently wicked than he [Byron] ever was". Even smart people have double standards, I guess.

32. Some Things Can’t Be Forgiven

When she was 36, Lovelace tragically perished of uterine cancer, but that day has gone down in history for an ever darker reason. Ada’s husband William abandoned his wife’s deathbed after a near-death confession. Historians suppose it was about her many infidelities, or the truth about her sister Medora. However, we may never know.

33. The Space Age's Hidden Figure

The 1950s was a time of opportunity and new frontiers, as all of America—and a good part of the rest of the world—turned their eyes to the moon, the stars, and beyond. But even as the US strove to break natural human boundaries, the Earth struggled to move past gendered and race-related discrimination.

Katherine Johnson, a Black woman and one of NASA’s mathematicians in the crucial early stages of the space program, had to break through both earthly and cosmic boundaries to fulfill her dreams and help get a man on the moon. The 2016 Hollywood blockbuster Hidden Figures already told some of her story, but there's still so much more to learn about this maverick woman.

34. A Gifted Child

Growing up in segregated West Virginia in the 1920s and ‘30s, Johnson showed an unusual talent for mathematics even as a child. Sadly, she didn't have an outlet for her natural skill. In fact, her county offered zero public schooling for Black children after grade eight. As a result, her parents had no choice: they had to send their daughter to high school in another county. Once she was in secondary school, though, Johnson flew through her classes. She even graduated at the ripe old age of 14.

35. Ahead of the Game

College followed the same pattern of advancement for Johnson. Entering West Virginia State, a historically black college, barely into her teen years, Johnson took no less than every single math course the school offered. Professors clamored to mentor her, including W. W. Schieffelin Claytor, who was only the third African American to receive a PhD in mathematics. In fact, Claytor designed special courses tailored specifically to Johnson.

She ended up graduating at 18, an age when most people are just entering college.

36. Breaking Boundaries

Johnson’s race already produced obstacles, but in 1939 her gender only made things worse. She dropped out of graduate school to raise a family with her first husband James Goble. After that, she taught but found it difficult to get a research position. In 1952, however, she heard from a family member that NACA, the predecessor to NASA, needed mathematicians to help calculate the numbers that would send men to space.

Johnson jumped at the chance. At first, NACA rejected her application—the positions were all full. But of course, the young woman knew how to persevere. She successfully reapplied in the next round and started work at Langley, Virginia in 1953. The sky was the limit—or so it seemed.

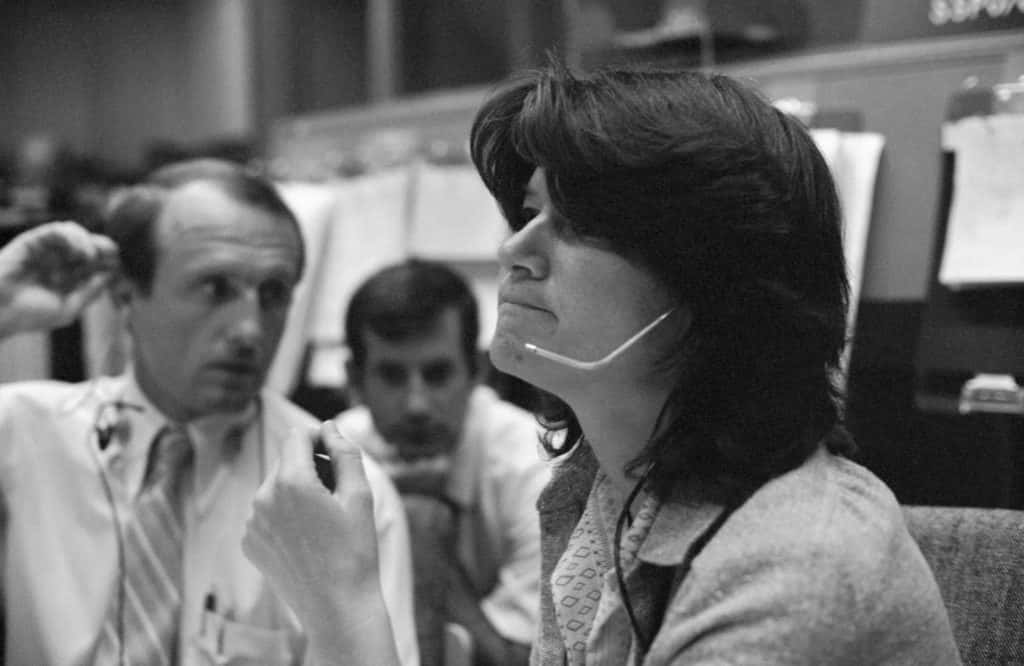

37. To the Moon and Back

Johnson’s time at NASA is the most talked-about event in her biography and the most lauded, but it was riddled with hurdles. While at NASA, she worked with a pool of other female “computers" (women who crunched the numbers that NASA’s white, male engineers decided they should crunch). Math is still gendered today as a largely male domain, and back then, NASA basically saw these female computers as glorified secretaries.

38. Computers in Skirts

Johnson called the women “computers who wore skirts,” near-automated, well-behaved lady employees. But for Black women, things were even worse. State segregation laws were still in effect, and Johnson and her other Black colleagues had to eat, work, and relieve themselves in separate facilities from NASA’s white employees.

39. Finally

Despite this environment, Johnson kept her head down. She even said she “didn't feel the segregation at NASA, because everybody there was doing research. You had a mission and you worked on it, and it was important to you to do your job". This laser focus soon would soon lead to sweet, sweet success.

One day, Johnson and another colleague received an exciting assignment. They would help the flight research team, which was made up entirely of men. Johnson worked studiously in the position, and her expertise in analytic geometry soon made her a permanent member of the team. As Johnson put it, “they forgot to return me to the pool".

40. The Great Divides

Johnson's humility is admirable but NASA did not simply “forget” to return her to the pool. She made herself absolutely indispensable because that's the only way to inch ahead in that environment. She recalls that women needed to be “assertive and aggressive” to receive any credit for their work. Indeed, women couldn't even put their names on reports.

One of Johnson's had to advocate heavily for her and then quit NASA entirely for Johnson to get credit on a report they co-wrote. Whatever Johnson did to advance, it was a continual struggle to not be forgotten or worse, ignored.

41. The Century of Johnson

But when John Glenn was about to become the first American man in orbit around the Earth, he remembered Johnson's brilliance. Glenn demanded that she personally check NASA’s numbers before he even considered taking off. Despite the attempts to erase her contributions, Johnson more than made her mark at NASA, the world, and the moon.

Other than Glenn's space trip, Johnson worked on the groundbreaking Apollo 11 mission, helped the ill-fated Apollo 13 get back to Earth, and received the vaunted Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015.

42. Ready, Set, Soar

Speaking of women who helped us take flight, why should Amelia Earhart get all the credit? Lilian Bland—despite her last name—led an exciting life. Not content with just being a sport journalist, Bland was the first woman in American history to design and fly her own aircraft. We guess you could call her The Aviatress. Take that, Howard Hughes.

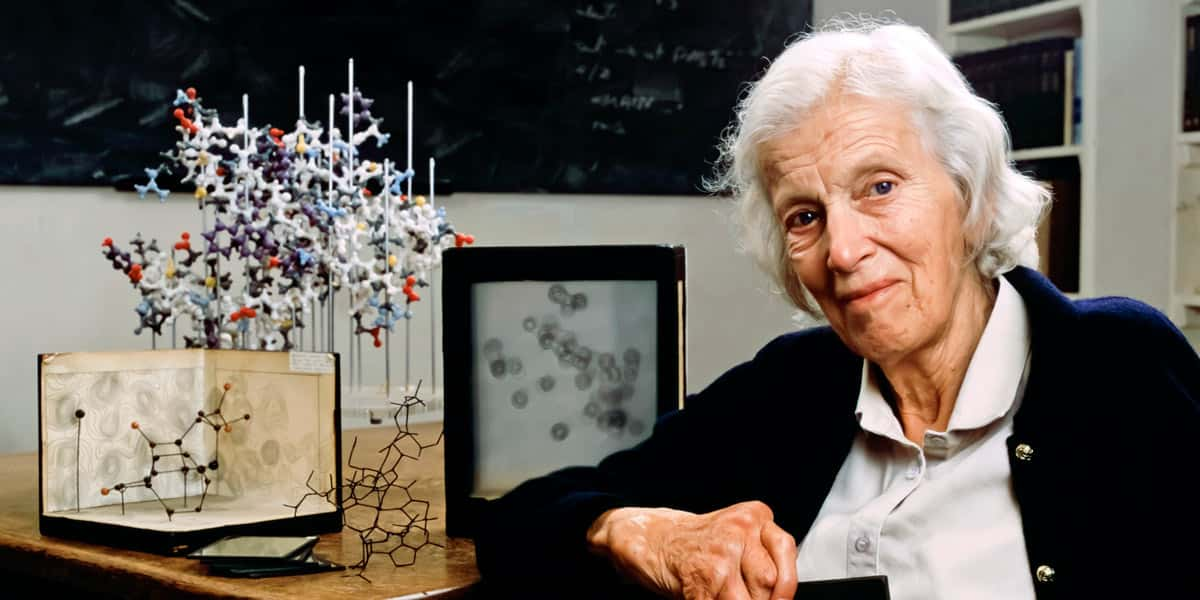

43. Miss Medicine

When she was only 26 years old, Dorothy Hodgkin discovered the structure of penicillin. That sounds kind of boring, but this was a HUGE deal. Hodgkin’s discovery meant that scientists could super-charge the drug and make it fight powerful infection strains. If that weren’t enough, she also discovered the structures of vitamin B1 and insulin. Simply put, disease beware. Hodgkin is coming for you.

44. It’s the Little Things That Matter

Beulah Henry had a fun nickname. Society called her “Lady Edison” because of, you guessed it, her Edison-like record of invention. Henry held 49 patents and over 100 inventions to her name, including a can opener, a hair curler, and even a vacuum ice cream freezer. Lord knows I couldn’t live without any of these precious items, so thank you, St. Beulah.

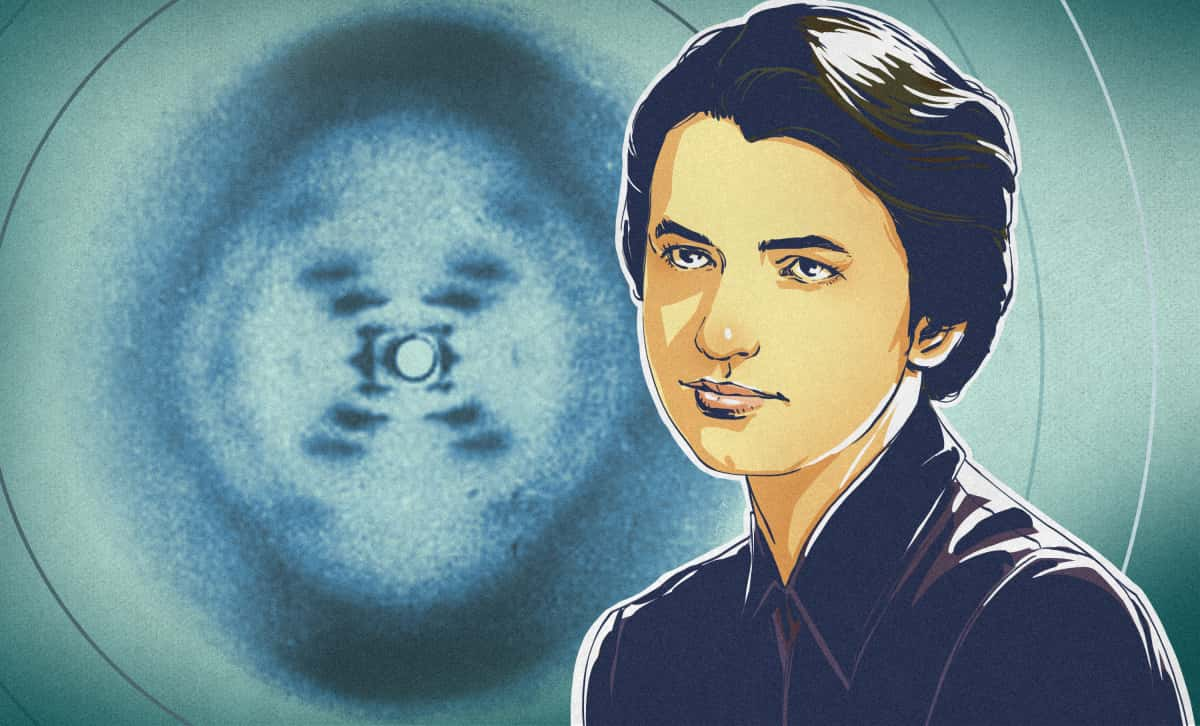

45. Grand Theft Science

If you can picture the iconic double-helix structure of DNA, thank Rosalind Franklin, who first captured “the secret of life” on film. Unfortunately, she suffered an utterly chilling offense. Francis Crick, James Watson, and Maurice Wilkins snatched Franklin’s discovery. Wilkins took Franklin’s photograph, known as Photo 51. Wilkins then showed the picture to Watson. The three men—Watson, Crick, and Wilkins—won the 1958 Nobel Prize for their discovery, without even mentioning Franklin. Boo. BOO.

46. Don’t Mess with This Doc

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker truly deserves a lush period drama adaptation. Not only did she work her way through medical school, Dr. Walker also acted as a spy in the Civil War, where she fought to end slavery. Walker crossed enemy lines to secretly care for servicemen imprisoned by Confederate troopers. When the South discovered her, she endured life (and injuries) as a prisoner of war.

For her bravery, she received the Medal of Honor in 1865. But since we never give women full credit, the commission revoked Dr. Walker’s medal in 1917. However, the good doctor refused to give the medal back and wore it proudly until her passing in 1919. Decades later, the commission realized their mistake and reinstated her medal in 1977. Uh, duh.

Bonus facts: Dr. Walker was also an abolitionist, a woman's suffrage activist, and did the lord's work by advocating for "dress reform". In other words, she worked hard so that women could stop squishing their organs with corsets and wear what they want (in Walker's case, pants). Ten for you, Dr. Walker. You go, Dr. Walker.

Wikimedia

Wikimedia

47. The Book of What?

For ages, scholars believed that the Trotula—a three-part medical text on women from the 11th century—must have a male author. As it turns out, Trota of Salerno was the pioneering author of the work. Scholars don't know very much about Miss Trota, except that she worked as a medieval OBGYN and deserves credit for her work.

48. Look to the Skies (So He Can Swipe Your Success)

In 1925, Cecilia Payne wrote a paper about the stars, uncovering exactly what elements form them. A male reviewer read Payne's essay but rejected her work because it went against the day's predominant thought. Lo and behold (emphasis on “low”), this same male reviewer published a curious paper four years later. It used Payne's ideas and came to the exact same conclusions. Hmm…

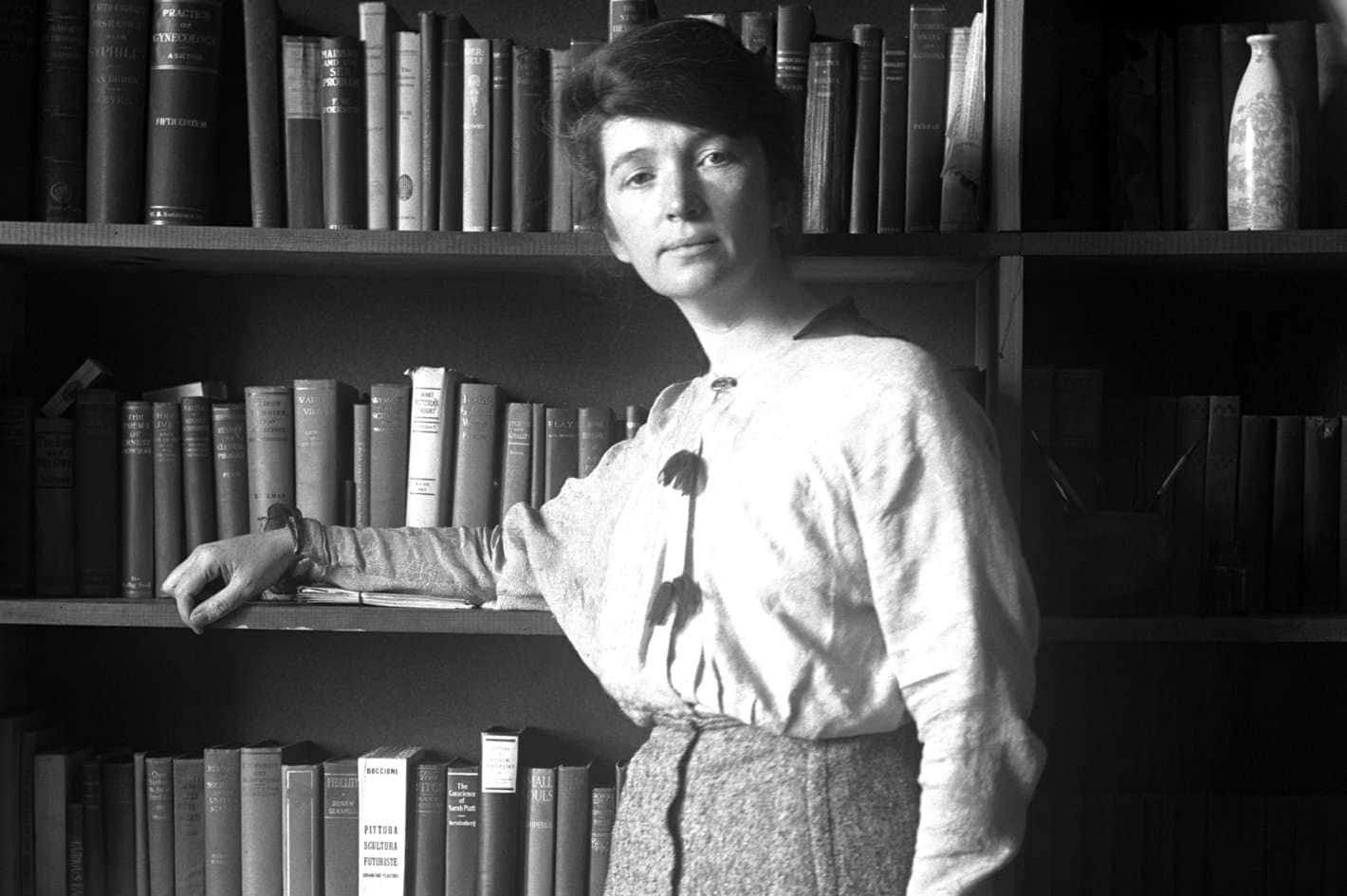

49. The Mother of Planned Parenthood

Beginning her career as a nurse, Margaret Sanger became a prolific writer, women’s health advocate, and political activist. She pioneered the term “birth control,” opened the first birth control clinic, and founded the American Birth Control League in 1921. This League later became the organization we now know as Planned Parenthood.

Sanger also founded a birth control clinic with only female doctors (the first of its kind) and organized a Harlem clinic whose advisory council only included Black men and women.

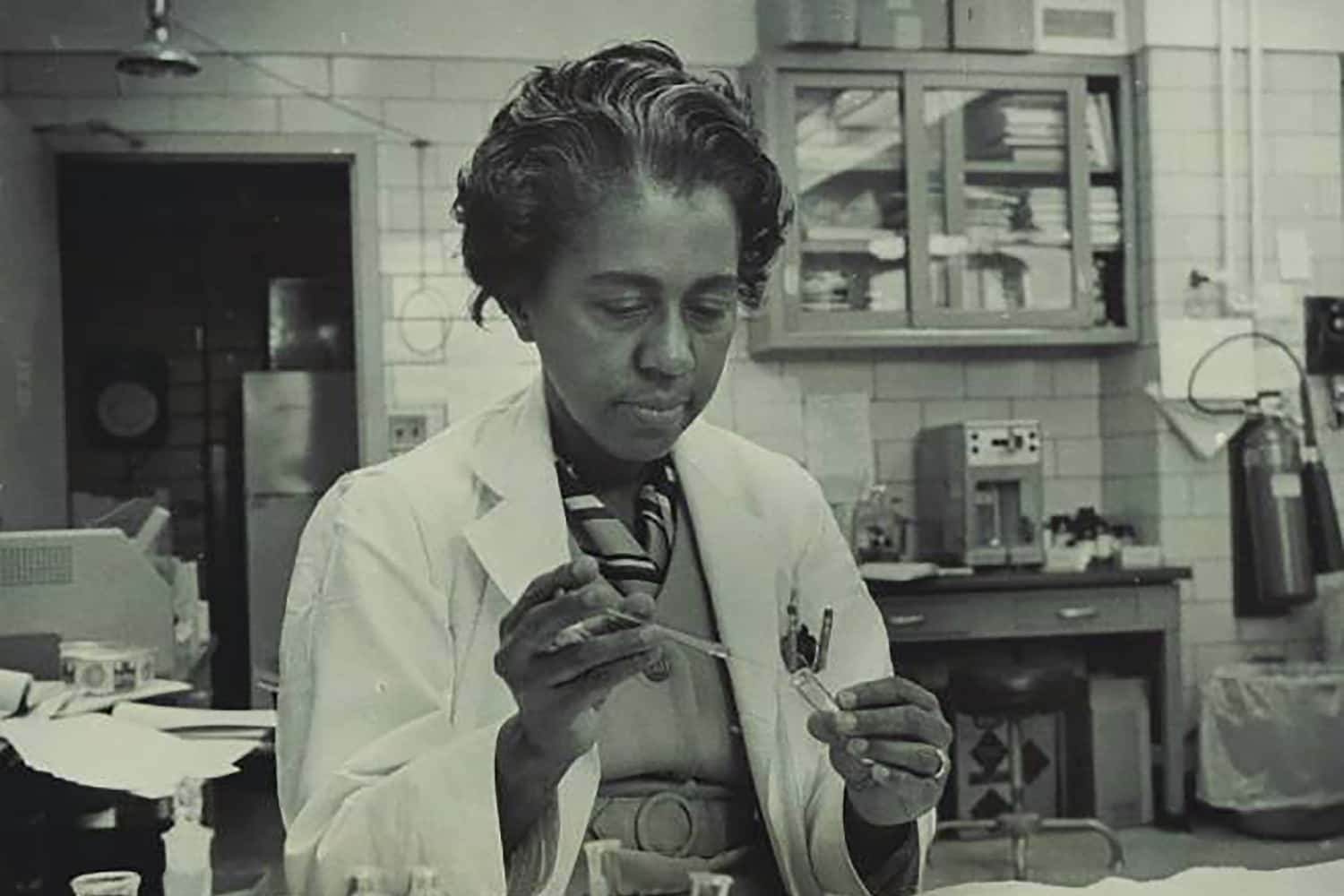

50. Science For All

Marie Maynard Daly was the first African-American woman to earn a PhD in Chemistry. After her historic achievement, she worked at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and made important contributions to the science of hypertension and the human circulatory system. But Daly didn't believe science was only for labs. She also used her prominence to advocate for other African-American students by establishing a scholarship and developing programs to encourage enrolment.

51. Where Few Women Have Gone Before

After graduating from medical school and serving in the Peace Corps, Mae Jemison joined NASA's astronaut corps. She became the first African-American woman to travel to space on the space shuttle Endeavour in 1992 and was the first real-life astronaut to appear on Star Trek. Jemison remembers that day fondly, saying that she admired Nichelle Nichols (Uhura in the original series) and loved being be part of the show. Dreams do come true, kids.

52. Coming Home

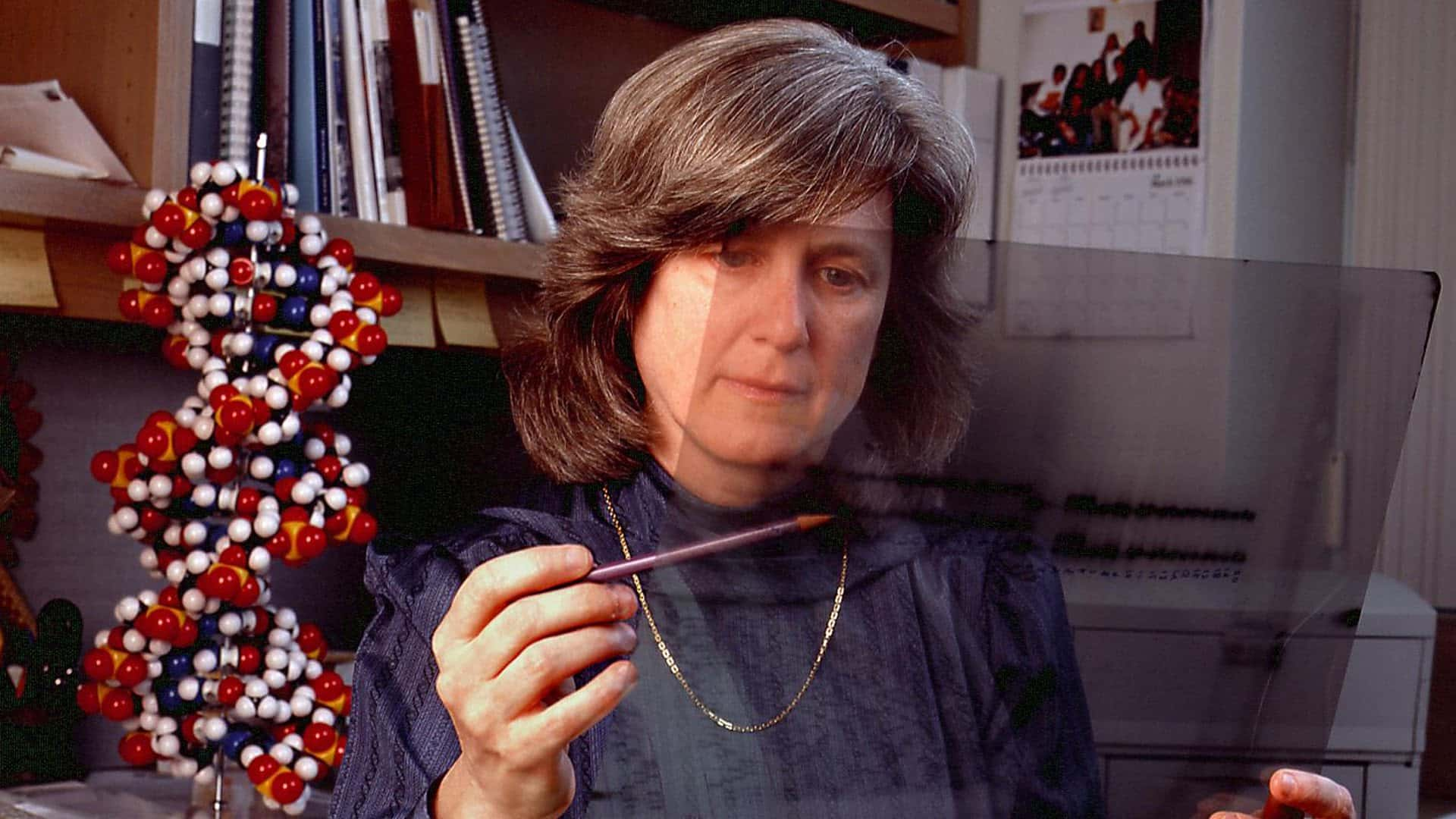

Mary-Claire King’s work as a geneticist has incredibly touching results. King used her knowledge to help Argentinian children reunite with their families after the civil conflict. She identified DNA links between orphaned and abandoned children and their relatives.

53. Cleopatra the Alchemist and the Philosopher's Stone

It might not be classified as science today, but Cleopatra the Alchemist was a foundational figure in 3rd-century science. Society considered her to be one of only four women who could produce the Philosopher’s Stone. It's super impressive that she received this credit. I mean, the 3rd-century didn't exactly welcome women in science.

54. Team Work Makes the Dream Work

In 1985, Chinese-American immunologist and molecular biologist Flossie Wong-Staal and her colleagues cloned HIV-1. By making a map of HIV-1's genes, the team changed everything: doctors could now test for the virus. Devoted to HIV science, Dr. Wong-Staal made several significant discoveries over her long career. Her work famously helped researchers learn about the link between HIV and AIDS.

55. Evil Keneval, Eat Your Heart Out

Surely one of the coolest lady scientists ever, Beatrice Shilling raced motorcycles in the 1930s. An aeronautical engineer by training, she invented “Miss Shilling’s orifice” (does that sound suggestive to anyone else?). The device was a small metal ring that prevented stalls in the carburetors of Rolls-Royce airplane engines, which were used in WWII fighter planes.

This allowed pilots to steeply ascend without fear their engines would stall and they would, you know, plummet to a fiery demise. All the swoons for Miss Shilling.

56. Cite Your Sources

Emmy Noether devised a principle, now known as Noether’s theorem, that was foundational to the field of quantum physics. Einstein based his famous calculations in part on Noether's theorem. He later said of her accomplishments, "It is really through her that I have become competent in the subject". Credit where credit is due, y'all.

57. Giving Back

Mary Jackson, one of NASA's “hidden figures,” was an engineer at NACA, which became NASA in 1958. After 34 years at NASA, she held the highest engineering position available, but her legacy truly centers around another incredible achievement. Jackson worked passionately to advance the hiring and promotion of women at NASA.

She managed the NASA Office of Equal Opportunity, the Affirmative Action program, and the Federal Women’s program.

58. Humanities VS Sciences

As an anthropologist and folklorist, Ruth Benedict seems like a weird person to be on this list, but her work was incredibly important for undermining racist pseudo-science. Benedict fought for cultural understanding and equality. She published pamphlets educating American troopers against racist beliefs. Through her work, Benedict showed that many of these race-related fallacies had no basis in scientific reality.

59. Victorian Period Jurassic Park

Mary Anning was a curious 11-year-old when she discovered her first fossil. What her brother dismissed as a crocodile turned out to be an Ichthyosaurus, an aquatic dinosaur. In her long career as a Victorian era fossil hunter, Anning taught herself anatomy, geology, paleontology, and scientific illustration. She also discovered hundreds of fossils from up to 200 million years ago.

60. Hedy Lamarr, The Mother of the Internet

“Any girl can be glamorous. All you have to do is stand there and look stupid".—Hedy Lamarr

That’s not very nice, but if anyone had the right to say so, it was Hedy Lamarr. Combining brains and beauty, Lamarr was a glamorous movie star by day and the mastermind (mistressmind?) of a scientific revolution by night. With her collaborator, George Antheil, Lamarr developed the groundbreaking technology that led to wi-fi.

However, like so many of the women on this list, Lamarr struggled to have her achievements recognized, all while dealing with Hollywood's dramatic dark side.

61. Seeing the Future

Despite her Jewish heritage, Lamarr married a fascist in 1933 when she was just 19 years old. Friedrich "Fritz" Mandl, a munitions manufacturer, was one of the richest men in Austria. When the pair married, he demanded that Lamarr officially convert to Catholicism. And that's just the beginning of this man's trash-fire qualities.

Lamarr's husband was also intensely jealous. For example, Mandl travelled Europe, buying and destroying every copy of Ecstasy (a scandalous movie starring Lamarr) that he could find. But there was one silver lining: Mandl insisted that Lamarr accompany him to business meetings where she listened to scientists discuss cutting edge science.

62. A Clean Getaway

Eventually, Mandl’s jealous, controlling behavior became too much for Lamarr, no matter how many nerd meetings she got to attend. When enough was enough, the actress fled Austria. Lamarr claims that she disguised herself as a maid and escaped to Paris, where she got a divorce. Other sources insist that Lamarr made an even more amazing escape. The story goes that Lamarr wore all of her expensive jewels to a dinner event, and then ran off into the night.

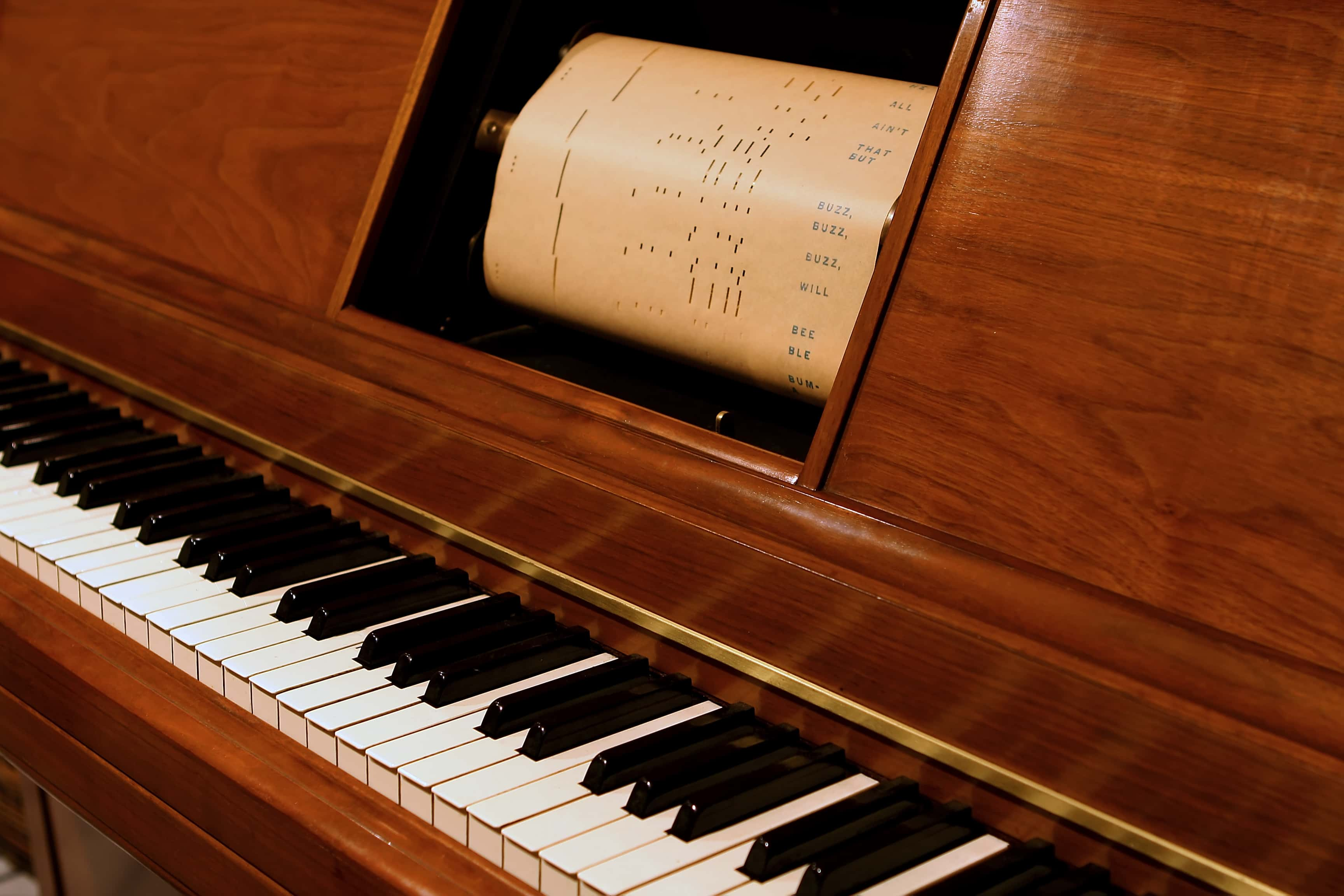

63. Can I Tell You a Secret?

When she wasn't escaping terrible men or starring in Hollywood hits, Lamarr worked on her scientific experiments, including an invention that would revolutionize communication technology. Inspired by the rolls used by player pianos, Lamarr and a collaborator, a composer named George Antheil, began working on something they called a “Secret Communication System".

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

64. Outsmarting the Enemy

Lamarr heard that the Navy had a major problem. Their radio-controlled torpedoes could be hacked by the enemy, then jammed and set off course. She believed that creating a signal that quickly hopped from one frequency to another would avoid such jamming. If the enemy could only hold onto the signal for a moment before it hopped onto a different frequency, maybe they could hack part of a message, but they could never ruin the whole thing.

This came to be known as frequency-hopping spread spectrum, and would later be used to developed all kinds of wireless communication technology. What modern day technology uses spread spectrum, you ask? Bluetooth, GPS, and wi-fi. Now that's a legacy.

65. The Patent

Lamarr and Antheil failed to actually produce a device that could effectively jump frequencies, but the idea was enough to secure a patent. In 1942, the US Patent Office granted “Hedy Kiesler Markey” Patent 2.292.387. However, Lamarr's patent was confiscated because of prejudice against Austrian immigrants, who were often considered to be enemy aliens. In the end, she didn't receive a penny for her incredible invention, even though it would be worth around $30 billion today.

66. Captain Marvellous

Frequency hopping wasn’t Lamarr’s only invention. She created an improved version of the spotlight and famously gave Howard Hughes tips on how to design his airplanes. Hughes, who Lamarr dated briefly (and unhappily--she called him her "worst lover"), gave her full access to his team of scientists and engineers for her own projects, but it was Lamarr's research into birds and fish that inspired her most important tip.

She showed Hughes that the fastest birds and the fastest fish shared certain shapes when they lunged and moved. At Lamarr's urging, Hughes made his planes less square and more streamlined, allowing them to go higher, further, faster.

67. Soda Stream, 1940s Edition

Hughes gave Lamarr two chemists to assist her with a project. In the end, she invented a tablet that turned water into carbonated drinks, taking special pride in a cube that transformed a regular cup of H2O into Coca Cola. The starlet found inspiration in stories from servicemen stationed overseas. They desperately missed home, so Lamarr figured out a way for them to taste America, even while abroad.

68. Nice to be Appreciated

Lamarr never won an Oscar. She was never even nominated. But she was the first woman to win “the Oscars of Inventing,” the so-called Bulbie award, when she was honored at the 1997 Invention Convention. In 2014, Lamarr was inducted into the Inventors Hall of Fame.

69. Life in Plastic, Not Fantastic

While Lamarr lived long enough to see her innovation recognized, her film career had long since dried up and she became reclusive. One devastating reason for Lamarr's withdrawal was her faded beauty. Lamarr was once the world's most gorgeous woman (legends say that Disney animators based Snow White on her facial features) but after some botched plastic surgeries, she became slightly disfigured.

Even when Lamarr was under the blade, she needed to innovate. Her plastic surgeons described how Lamarr would come to them with ingenious ideas for lifting, cutting, and pulling skin so that she would appear more youthful. Apparently, surgeons still use some of her ideas to this day.

70. Sally Ride

In 1983, Sally Ride became the first American woman (and the youngest person) to go into outer space, mere decades after Star Trek introduced the idea to pop culture. With a PhD in physics from Stanford, an extensive career with NASA, and an inspirational personal life, Ride is truly a scientific (and social) icon.

71. In on the First Attempt

In 1978, NASA selected women for their astronaut training for the first time in the organization’s existence. After reading an advertisement in the student newspaper at Stanford University, Ride put forward her own application. NASA chose her to be part of NASA Astronaut Group 8. History was about to be made.

72. Professional Relationship

In 1982, Ride married Steven Hawley, one of the other astronauts on NASA Astronaut Group 8 (Hawley would go into space two years after Ride made her first space voyage). But the couple was doomed to a heartbreaking end that would only make sense years too late. The couple finalized their divorce in 1987.

73. Worst-Case Scenario

Ride said that during her times in space, there were thankfully no close calls or near disasters. She admitted, however, that launching was always thrilling and dramatic moment. Fair enough. On January 28, 1986, the space shuttle known as Challenger broke apart less than two minutes into its tenth flight.

All seven of the people on board perished during the disaster. At the time, Ride was eight months into training for her third ride into space.

74. When My Heart Stopped

The Challenger disaster devastated the American nation, but Ride took it even harder than most. Four of the deceased astronauts were in her class, meaning that she knew them closely for years before the disaster. Despite this closeness to the tragedy, Ride served on the investigation committee formed in the aftermath of the tragedy.

75. Showing Solidarity

Six months before the Challenger disaster, one of the engineers tried to warn the construction company that a terrible incident could happen. While the workplace promptly shunned its whistleblower, Roger Boisjoly, Ride publicly supported him. Tragically, she was the only one. Boisjoly later credited Ride with being the only person on his side.

76. Love of My Life

It wasn’t until after Ride’s passing that she became the first LGBTQ+ woman to go into space. Ride was the long-term partner of university professor and writer Tam O’Shaughnessy. The women began their relationship in 1985 and remained together until Ride’s passing.

77. Meant to Be

Ride’s relationship with Tam O’Shaughnessy actually went back to Ride’s early years playing tennis. The pair met while competing in tournaments and remained close for the rest of their lives, eventually becoming romantic partners. Interestingly, O’Shaughnessy was mentored by none other than tennis playing legend Billie Jean King, who was also one of Ride’s childhood heroes, and a fellow lesbian icon.

78. In the Name of Science

In 2001, Ride and her partner, Tam O’Shaughnessy, founded the company called Sally Ride Science. Based in San Diego, the company strives to encourage young people to pursue science, mathematics, engineering, and technology. It also runs several different programs which provide professional development to teachers and encourage students to pursue the sciences.

79. Wait, What?!

As many of you can sadly imagine, Ride endured some baffling questions from the media before going into space. Among the most ludicrous questions allegedly thrown her way were “Will the flight affect your reproductive organs?” and “Do you weep when things go wrong on the job?” We’d like to say that the 1980s was a different time, but we still have a long way to go.

80. Honorable Mention

In the late 1980s, the LGBTQ+ community in the United States fought many battles for their civil rights, even as the AIDS crisis claimed so many lives. One project which emerged from this period was the Legacy Walk in Chicago. This outdoor public display is a celebration of the contributions that LGBTQ+ people made to world history. After Ride’s orientation was revealed, she received proper mention. In 2014, Ride was inducted into the Legacy Walk.

81. One Small Laugh for Man, One Giant Leap Backwards for Womankind

Did you know that NASA held beauty pageants until the 1970s? Yup, and they weren't the only ones. Several science organizations—from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to the Lewis Space Center—held beauty competitions with colorful names such as “Miss NASA” (of course), “Miss Guided Missile” (okay, that’s clever), and “Lunar Landing Festival Queen” (they’re scientists, not poets).

Who didn’t find it funny? Well, NASA pressured some women employees into participating. They didn't love the idea—but don't worry. They had the last laugh.

82. Too Manly to Take a Joke

In protest of the chauvinistic “Miss NASA” competitions, a group of women swapped the ballots with joke slips where workers could vote for one of 45 male NASA employees for “King of the court” (or more demeaning, “Boy of the court”). Faced with a challenge from mysterious forces, the men bravely freaked the heck out and called security.

Nevertheless, the “results”—featuring cartoons of the winners themselves—were shared among workers the very next day. This shocked the men so deeply that they canceled the Miss NASA competition before it could ever launch again. Point, set, match. Now, where's that Men of NASA commemorative calendar?

83. The Lady With the Lamp

Florence Nightingale requires little introduction to anyone interested in medical history. The Victorian nurse’s name is shorthand for first-class bedside care, but few people know that Nightingale's social reforms changed modern medicine both on and off the battlefield forever.

84. One of the Guy’s Girls

When she was 18 years old, Nightingale began a lifelong friendship with the writer and intellectual, Mary Clarke. Although Clarke was 27 years older than Nightingale, age ain't nothin' but a number, baby. The women were great friends and Mary Clarke influenced young Nightingale with her masculine manners, eccentricity, and ambitious pursuits that, to anyone else, would be seen as "for the boys".

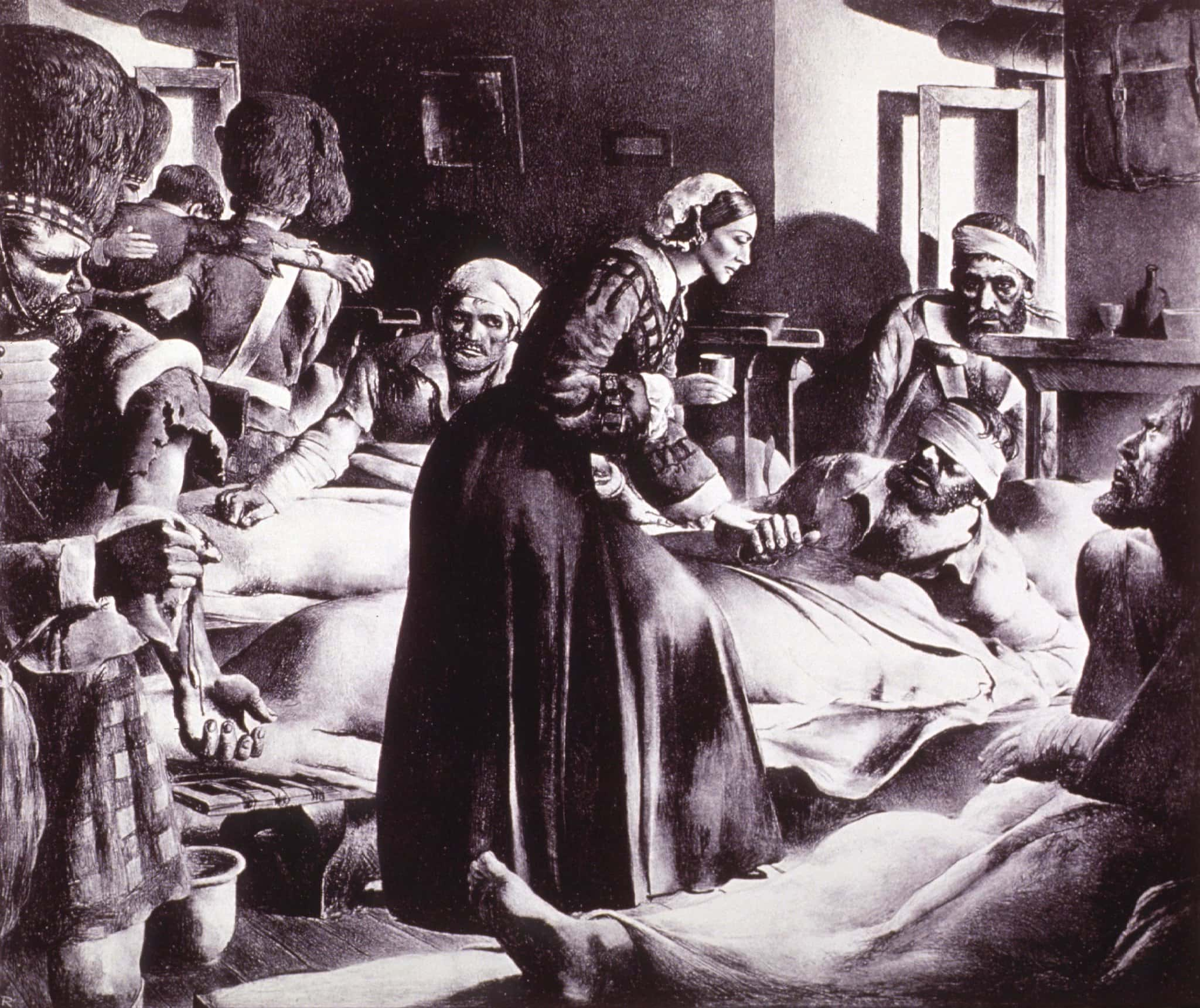

85. Not Today, Grim Reaper

Though it's a horrific thought, rat faeces and rodents themselves weren’t uncommon sights in Victorian combat hospitals. Florence Nightingale, not super impressed with these terrifying conditions, deduced a then “radical” notion. Her wild idea? Lousy sanitation just might lead to dying. Leading a brigade of 38 nurses, Nightingale led a cleanliness crusade.

Nightingale and her nurses overturned medical services during the 1850s Crimean conflict. Thanks to her reforms—and the work of the nurses—mortality rates in the hospital where she worked dropped from 40% to just 2%.

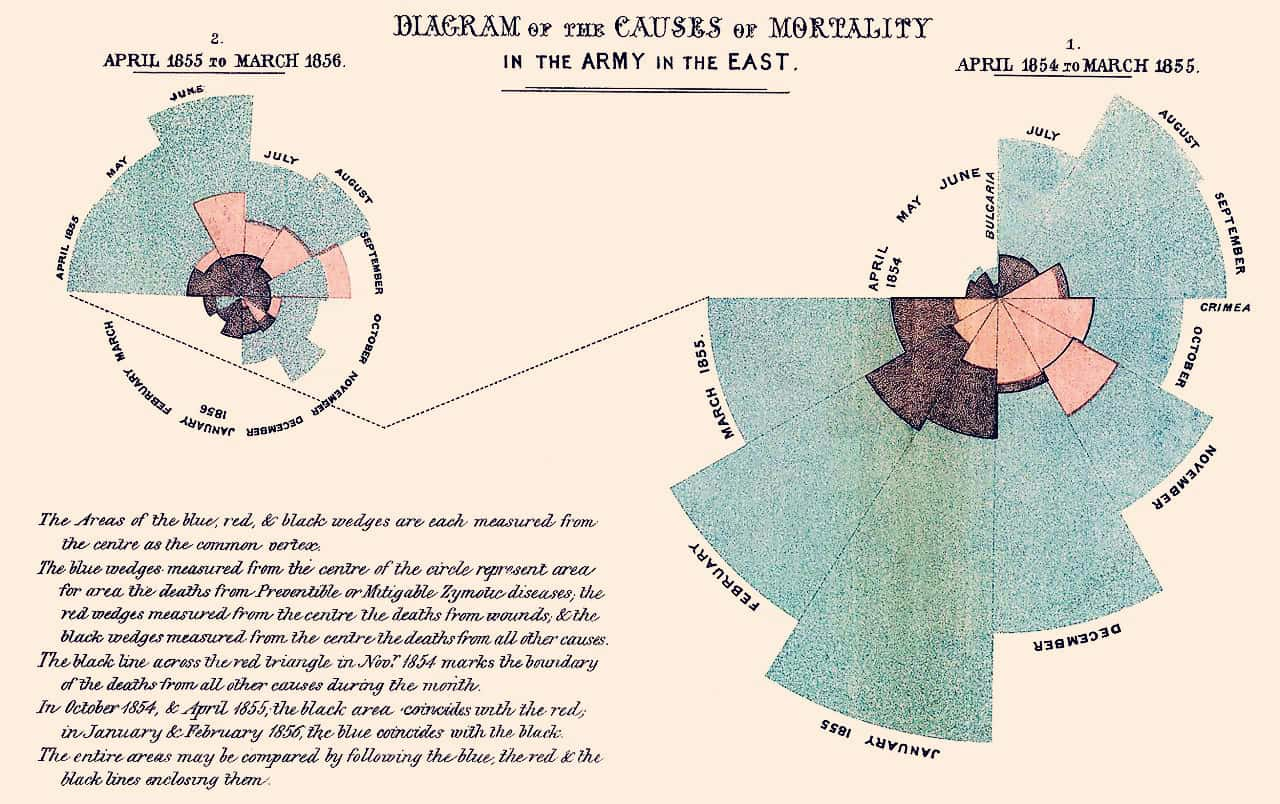

86. It’s As Easy As Pie

You like pie charts? Thank Florence Nightingale for popularizing the use of the infographics in journals and print culture. Although she didn’t invent the pie chart—they were first drawn in 1801, some 19 years before her birth—Nightingale adapted the diagrams for her public medical reports. In a famous 1858 document, she used the chart to display the varieties of conflict casualties. Like Marie Curie, Nightingale valued clear communication.

87. Her Majestic Fandom

Queen Victoria was a big-time Florence Nightingale groupie. She even sent the nurse a specially-made broach for her service. It came with a note that read, "It will be a very great satisfaction to me...to make the acquaintance of one who has set so bright an example to our [gender]". The pair met in 1856 and stayed pen pals for the rest of their lives.

88. The Battle at Home Will Save Lives

After the Crimean War, Nightingale brought her sanitation crusade home. In the early 1870s, she pushed for a policy that would make sure English buildings connected to main drainage systems. She asked a startling question: if the army got clean water and conditions, why not citizens? The proof of Nightingale’s efforts lies in the numbers.

By 1935, when the ambitious legislation took effect, the national life expectancy shot up by approximately 20 years.

89. Pay It Forward, Flo

After becoming rich from a $250K prize, Nightingale donated all her cash to a noble cause. She helped build St. Thomas' Hospital, as well as the Nightingale Training School for Nurses.

90. Reading Pain-bow

Nightingale used basic English to write her medical books and reports. Paired with her use of readable infographics, she played an instrumental role in making health knowledge accessible, even for those with low-level literacy. Over her life, Nightingale wrote about 200 books, articles and pamphlets—and only some of these were related to medical professionalism. She also tried social writing, religious treatises, and even engaged with Roman mythology.

Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome Images

Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome Images

91. RN of the Thinkpiece

Few people know that Florence Nightingale wrote “Cassandra,” a Victorian feminist polemic that lambasted society for socializing women to be weak. She cites how her mother and sister fell into “lethargy,” even with their good education. She also discloses her fears that she might become like the mythical Cassandra, a princess of Troy cursed with foresight that no one believes.

Nightingale totally would have gotten along with Dr. Mary Edwards Walker. She also hated social constraints that hurt women, focusing especially on clothing. Dr. Walker wrote about how voluminous skirts trapped bacteria. She wore pants under her own skirts and over time, just wore pants out in the open. Living the dream.

92. Good Living for All

Nightingale advocated for hunger relief and sex workers’ health in India. In the 1860s, the British government tried to introduce a law that forced women sex workers to receive medical examinations by the state—with no mandatory testing for men, of course. Although she held generally anti-sex work views, Nightingale still fought against this discriminatory legislation. From her research, she saw it as unfair—and also just plain ineffective in preventing the spread of venerable disease.

In her formal analysis, she saw the bill as informed by a double standard that had little medical basis. Instead, she and other opponents of the bill saw health as determined by social factors like poverty and diet, rather than gender and purity. Nevertheless, she only succeeded in getting the bill’s passing slowed down, not abolished.

93. Time for an Upgrade

Nightingale's family, especially her mother and sister, never supported her decision to go into nursing—though, to be fair, they were right to wish “better” for her, considering the time. In early Victorian England, nursing was not a great scene. It was full of alcoholism, low wages, and nurses sometimes made ends meet with sex work. These days, we credit Nightingale with bringing “respectability” to the once-scandalous profession.

94. Nursed to the End?

In 1861, Nightingale was accused of ending a statesman with cleanliness. Or rather, people whispered that her pressure for healthcare reform sent Sidney Herbert to an early grave…though his case of Bright’s Disease certainly helped.

95. Partner in Arms

Despite her “implication” in his passing, Sidney Herbert was good friends with Nightingale, whom he met on his honeymoon in Rome. He would be Secretary of War on two separate occasions, during which Nightingale served as a close political advisor.

96. Who Nurses the Nurse?

Nightingale never fully recovered from a bacterial infection that she contracted during the Crimean War. While crusading for cleaner hospitals, she herself became almost fatally sick with Crimean Fever. For the rest of her life, she suffered from reoccurring symptoms, but kept her struggles hidden to pursue her work.

But Nightingale also suffered from something even worse. Partly related to her long-term battle with illness, Nightingale struggled with long-term depression. Her experiences with mental illness affected her writing so much that Nightingale, once prolific, produced less and less material as her life ended.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90,91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108