A Watery Grave

Around 1300 BCE, a merchant ship plunged into the depths of the Mediterranean, dooming a fabulous cargo of exquisite crafts and valuable raw materials. 33 centuries later, a sponge diver chanced upon the Uluburun shipwreck, revealing details of ancient life and luxury.

Great Fear

Uluburun means “Grand Cape” in Turkish, but for sailors over millennia, it’s been a treacherous threat piercing the southern coast of Turkey. And in 1982, it was in its waters that Mehmed Çakir would stumble upon a shipwreck’s startling riches—while hunting a much more modest quarry.

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Creature Comforts

Today, we have the option of cheap, artificial sponges, imitations of natural species first used by the ancient Greeks. But the Mediterranean Sea has long been a harvesting ground for the softer varieties of this creature, used not just for bathing, but to make helmets, cups, and filters.

Solomonn Levi, CC-BY-SA-4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Solomonn Levi, CC-BY-SA-4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Hunting Time

And like coral, sponges are animals, not plants, even if they stick to the deep ocean floor and stay put. The depths of Grand Cape had hid this shipwreck for what might have been forever. But once the underwater hunter returned to the surface, hunters of a more scientific nature would soon follow.

Georges Jansoone, Jojan, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Georges Jansoone, Jojan, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

First Hints

The diver sketched “metal biscuits with ears,” exciting the experts at the nearby nautical museum. They realized Çakir had found oxhide ingots, their four handles giving them the appearance of stretched animal skin. This was a hint of the 10 tons of copper to come.

What are the unknowns of Uluburun Shipwreck? | In the Footsteps of History, Haberturk TV

What are the unknowns of Uluburun Shipwreck? | In the Footsteps of History, Haberturk TV

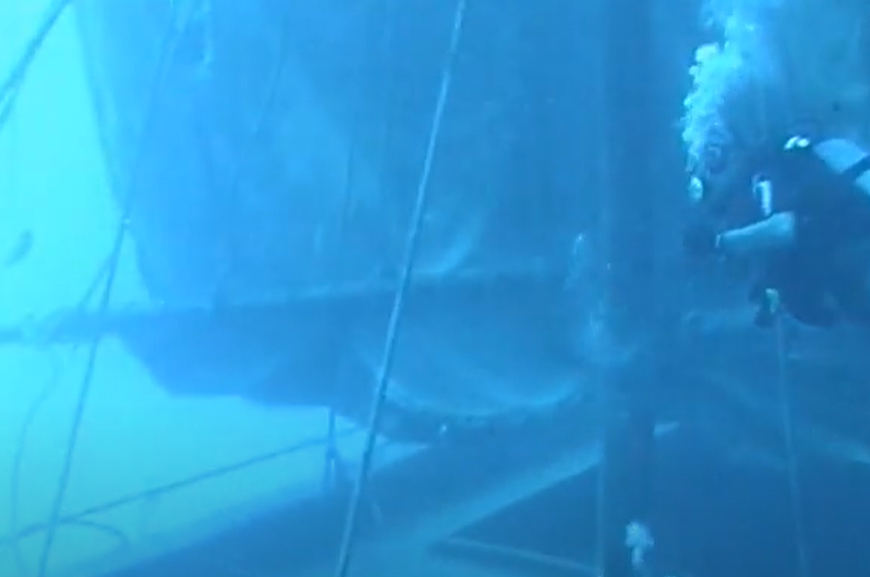

Breadth And Depth

But getting to the wreck would be a big challenge. It wouldn’t be hard to sail 160 feet (50 meters) from the elegantly named Turquoise Coast, but descending that deep beneath the waves would form the bulk of the challenge. Luckily, a modern ship would help.

What are the unknowns of Uluburun Shipwreck? | In the Footsteps of History, Haberturk TV

What are the unknowns of Uluburun Shipwreck? | In the Footsteps of History, Haberturk TV

Siren Call

The Institute of National Archaeology (INA) had a ship called the Virazon, key to the recovery operation started in 1984 under George F Bass. Also key was a strange piece of equipment called an “underwater telephone booth,” which Bass had employed on previous projects.

What are the unknowns of Uluburun Shipwreck? | In the Footsteps of History, Haberturk TV

What are the unknowns of Uluburun Shipwreck? | In the Footsteps of History, Haberturk TV

Vital Decompression

Four divers could shelter under its dome filled with air, and they could also communicate with their surface ship. But divers also had to contend with the requirement to decompress, moving up slowly once finished with their dive, otherwise they’d “get the bends,” which could prove fatal.

What are the unknowns of Uluburun Shipwreck? | In the Footsteps of History, Haberturk TV

What are the unknowns of Uluburun Shipwreck? | In the Footsteps of History, Haberturk TV

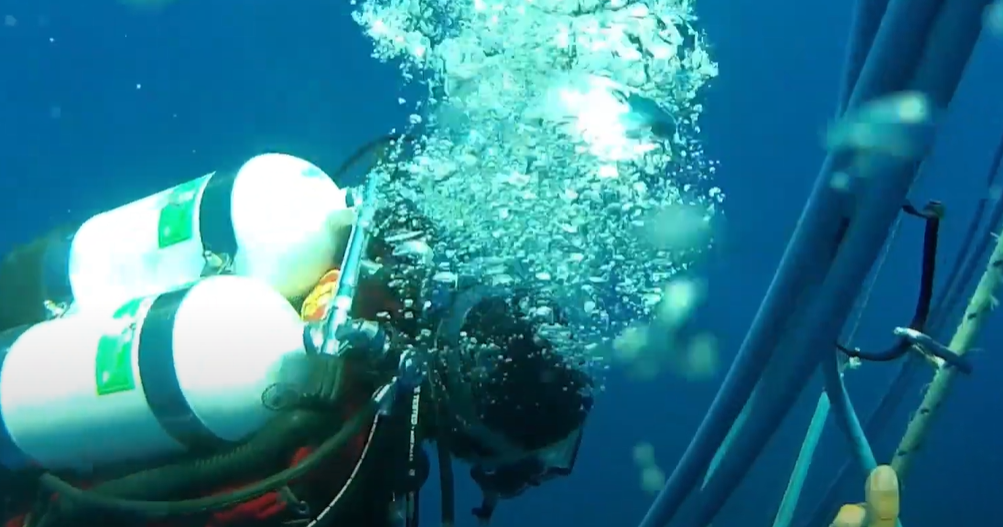

Caught In A Bubble

The great pressures of ocean depths can dissolve gases in the bodies of divers. Back at the surface, these gases can produce bubbles in divers who return too quickly. To prevent injury or death, divers have to move up slowly or use a decompression chamber for some time.

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

Slow But Spectacular

So the project was going to be dangerous and time-consuming. Under Bass and then Cemak Pulak, the project made over 22,000 dives, with many artifacts now on display at the nearby Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology. But finding answers has also taken time.

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

A Matter Of Timing

A basic problem has been deciding when this ship, passengers, and cargo met their doom. Tree rings help, as they form patterns over the years and centuries. One badly deteriorated branch suggested 1305 BCE or later. Radiocarbon dating of plants pointed to a timeframe of 1335 to 1305 BCE.

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

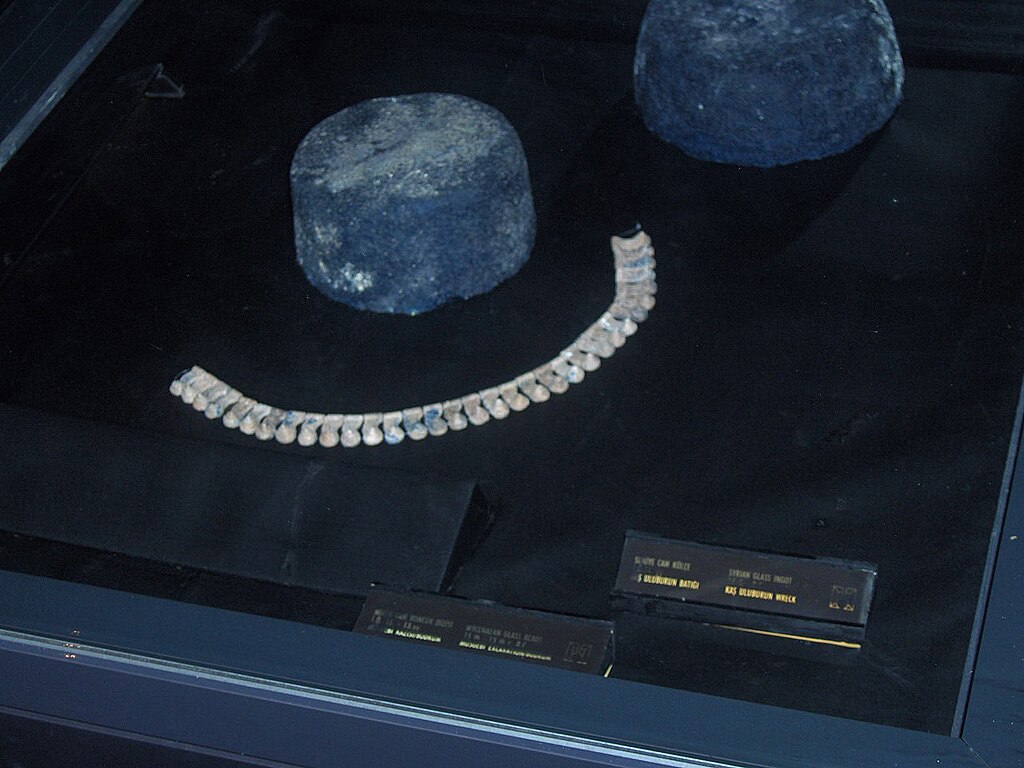

A Perfect Mix

All this suggests the Bronze Age, which lasted from around 3300 BCE to 1200 BCE. It was a pivotal time, nestled between the Stone Age and the Iron Age. And the ship was carrying the exact right 10:1 ratio of copper and tin ingots for producing a lot of the bronze which gave this time period its name.

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

New And Improved

Bronze tools—and weapons—were stronger and sturdier than stone weapons, making the alloy enormously valuable. Had the ship not sunk, researcher Michael Frachetti says, the ingots would have produced 11 tons of high-quality bronze, enough to forge 5,000 swords.

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

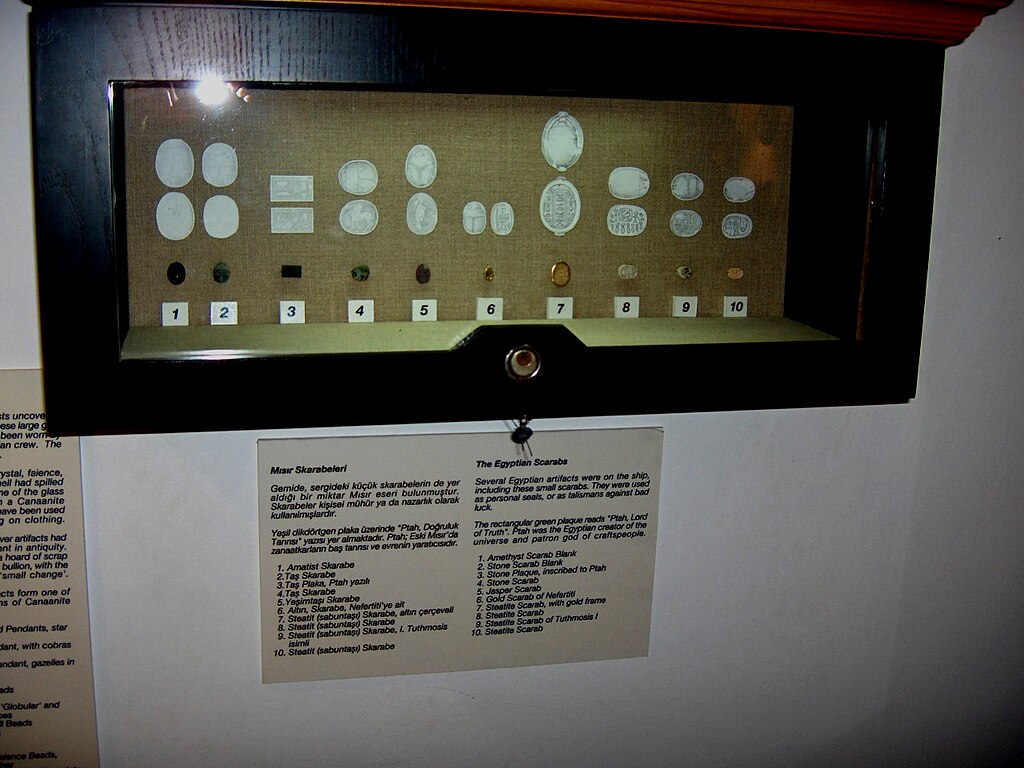

Tin Has Its Rewards

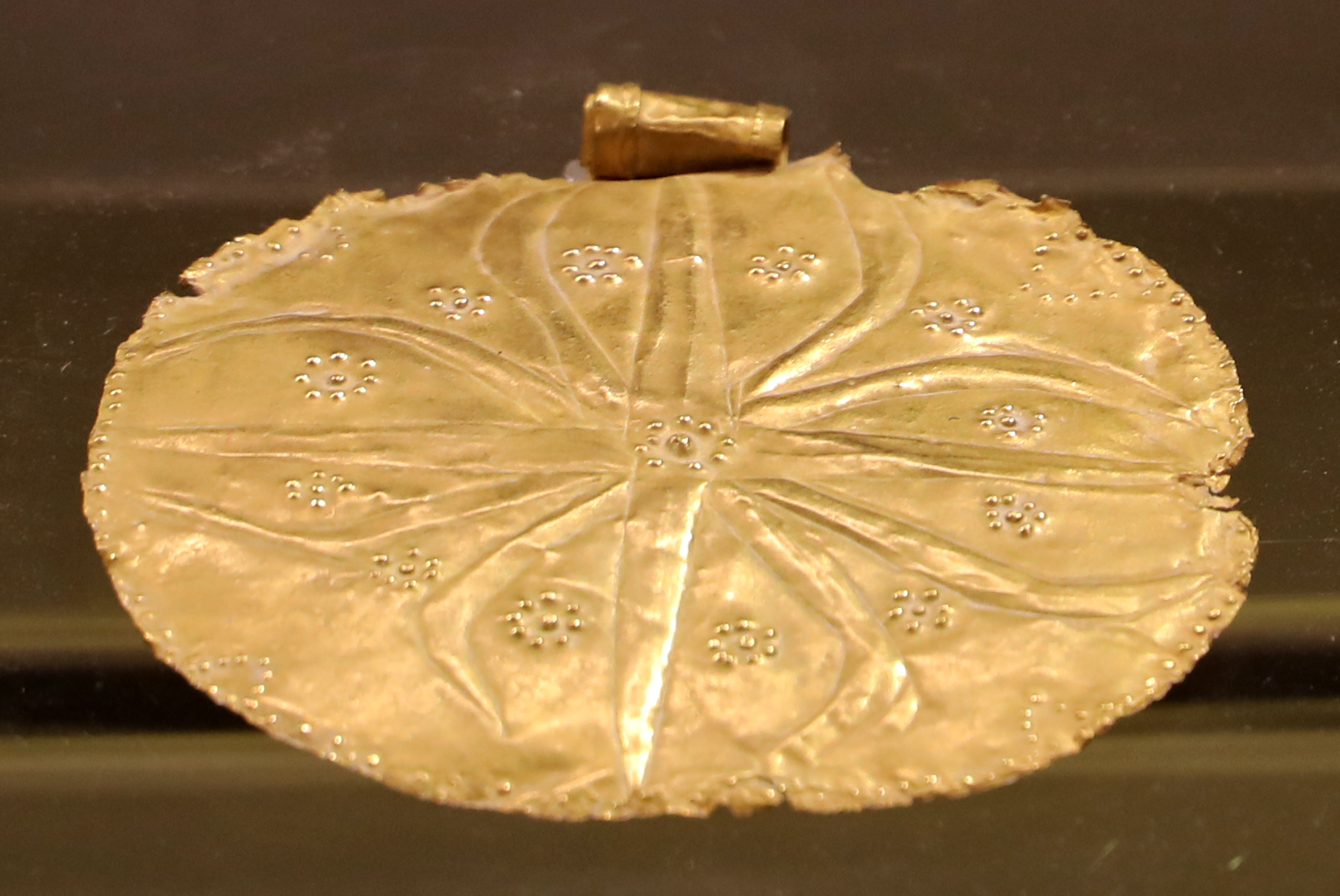

But tin was particularly hard to find, and almost never discovered in the same place as copper. A bustling trade resulted, helping to explain the rich variety of the Uluburun shipwreck’s inventory. Elegant items included Egyptian jewelry, such as golden pendants shaped as a disk, falcon, or goddess.

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

Ebony And Ivory

There were silver bracelets and ostrich eggshell beads as well. Larger items on board included logs of blackwood, which Egyptians called ebony, as well as ivory tusks. Also lying on the rarefied end of things were an Italian sword, Baltic amber, and Mesopotamian cylinder seals.

Francesco Bini, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Francesco Bini, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Gift Exchange

These were not the staples of the common folk. Instead, these luxury items seem to fit into a pattern of rulers exchanging gifts across kingdoms. Nonetheless, four balances (with weights) that were found on the ship strongly suggest trade and commerce. But from where to where?

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

Discover Decompression Diving with National Geographic Explorer Lisa Briggs, National Geographic UK

Westward Bound

The ship was likely sailing westward when it met its fate, perhaps after a quick stop at a nearby port in Lycia. Evidence for this springs from lots of pottery that originated in Cyprus, while there were few items from Greece. Cyprus is east of the shipwreck, while Greece is to the west.

Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sails And Resales

A lot of the pottery used clay associated with Ugarit, an ancient port city in northern Syria, which also suggests the ship came from the east. But there’s a caveat. With such a large web of trading routes, many items could be sold and resold, further muddying the waters.

Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Finding A Market

And it seems to have been a very extensive web. In 2022, Frachetti and other researchers revealed that much of the tin on the ship came from present-day Uzbekistan, where animal herders’ footpaths were the norm, not the speedy expressways of faraway empires.

Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Ton Of Effort

Local miners somehow got their product to market in multiple stages, including the arduous journey from Iran to Mesopotamia—moving tons of heavy metal, not lightweight jewelry. The other two-thirds of the tin on the Uluburun shipwreck came from Anatolia, namely present-day Turkey.

Georges Jansoone, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Georges Jansoone, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Supply Chain and Demand

So the Uluburun shipwreck appears to have been traveling one link in a very long supply chain, transporting fancy gifts, raw materials, and everyday items to important markets. But beyond the goods, who were the people on board that ill-fated ship? Geography tells us a little, but not a lot.

Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Wide Net

Recovered artifacts came from nearly a dozen cultures situated in a wide area from the north of Europe to Africa, and from Sardinia to Mesopotamia. Some scholars think Greek officials would have accompanied these goods, perhaps to grease the wheels of international diplomacy.

Georges Jansoone, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Georges Jansoone, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Heavyweight Action

Some artifacts would have belonged to the crew, or been used by them, whether personal jewelry or pots for the galley. But the four scales suggest that merchants from Phoenicia or Canaan (around Lebanon) were making the journey. And one of them may have been the boss.

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Upscale Items

A fancy set of weights came in the shape of animals, and a Phoenician sword, just as impressive, had a handle with ebony and ivory inlays. Maybe they belonged to the same person. This well-accessorized individual could even have been the ship’s captain himself.

Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Crew Clues

Some artifacts were Mycenaean, a culture that flowered on mainland Greece, Crete, and neighboring islands, and on the western shores of Anatolia. Much of the crew’s pottery was Mycenaean, so perhaps Mycenaean palaces were frequent destinations for the ship.

Sharon Mollerus, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sharon Mollerus, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Cyprus Connection

Some pottery and oil lamps originated in Cyprus, along with the nine large Cypriot containers on board. But the wide variety of Cypriot pottery suggests the source was a reseller who’d collected items from various parts of the island, instead of a single factory selling direct to the ship’s merchants.

Georges Jansoone, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Georges Jansoone, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Point To Haifa

If the boat didn’t start its journey in Cyprus, then where did it come from? How the boat was constructed, the style of the ship’s 24 stone anchors, and the type of pottery used by the crew point to Tell Abu Hawam—present-day Haifa, Israel—or some other port in the Levant.

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Follow The Resin

Also making the case are the 130 jars of terebinth resin. Analysis of the pollen shows it came from present-day Israel. It’s the biggest such find ever, though it’s not entirely clear what the recipients intended to do with all that resin. Perfumed oils and incense are two possibilities.

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Sizing Up The Wreck

Another source of mystery is the ship itself, which had mostly disintegrated over the millennia. But it’s believed it was about 50 feet or 15 meters long, 20 feet or 6 meters wide, and could handle up to 20 tons of cargo. Around 17 tons of goods were recovered by divers.

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

The Lebanon Connection

There was some planking that survived, and parts of the rudimentary “proto-keel,” both of which were made from Lebanese cedar. But wood doesn’t particularly enjoy the salty depths of the Mediterranean, so we have only partial evidence. And evidence is missing on a larger question.

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

The Twilight Hour

The doomed vessel sank by 1300 BCE, it seems, just a century or two before the Bronze Age itself met its doom. Trade routes and Mycenaean palaces alike would soon collapse, turning an interconnected web of civilizations into a sad array of myth and debris. So what happened?

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Half Collapsed

Throughout the eastern Mediterranean, towns and cities burned to the ground, with society becoming focused on village life. With the collapse of trade, the mighty fell and the poor got poorer. At least that’s the party line—some scholars think the collapse is overstated.

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Iron Will

The more dramatic explanations include invaders, earthquakes, plagues, and droughts, but it may have boiled down to a question of iron. Around the 13th and 12th centuries BCE, the secrets of smelting iron slowly spread through Europe, starting in Bulgaria and Romania.

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Heating Up

Iron was stronger than bronze, and a lot easier to find than the scarce tin used to make most bronze. So once the higher temperatures required for working with iron could be achieved, armies could be equipped with iron swords and other iron weapons, with fearsome results.

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Bigger And Better

With iron readily available, armies could be both larger and stronger, easily able to overpower traditional Bronze Age opponents. And with sources of iron close by, elaborate trade routes to obtain tin faded in importance. So societies no longer had that big incentive to cooperate.

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Explorer Classroom | Underwater Archaeology with Lisa Briggs, National Geographic Education

Rocky Seas

There was also an Icelandic volcano that may have caused a year-round winter, and pesky Sea Peoples, apparently pirates who liked to disrupt supply chains. But whatever the causes, the kind of journey—and cargo—our doomed ship had taken would soon be, well, history.

Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen, Ancient Apocalypse, The Mystery of the Sea People

Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen, Ancient Apocalypse, The Mystery of the Sea People

An In-Depth Look

And you can glimpse this history at the Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology, located not too far from the shipwreck’s not-so-final resting place. Its special hall dedicated to the Uluburun shipwreck features an array of recovered artifacts—and a lifesized replica of the ship.

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Grim Exhibits

The museum is situated in Bodrum Castle, completed around 1437 by four European powers, only to be taken over by the Ottoman Empire in 1523. The castle’s present tenant boasts being the world’s largest museum of shipwrecks, and features five other exhibits on similar disasters.

I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Seaworthy It Seems

Turkish researchers built and sailed a replica of the Uluburun ship, using only techniques known in the Bronze Age. Fortunately the reconstruction fared better than the original. However, another replica did sink—but on purpose, so it could be added to an “archaeo-park” near Kaş, Turkey.

Francesco Bini, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Francesco Bini, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Interrupted Journey

Smashed against the rocks of southern Turkey, the vessel that would become the Uluburun shipwreck left the lives of passengers and crew lying in ruin at the bottom of the sea. But 33 centuries later, the ship and its cargo have let us take our own journey into the deep past.

You May Also Like:

The World’s Eeriest Shipwrecks

Photo Of Massive Ship Graveyards Around The World

Researchers Have Discovered America's Last Known Slave Ship

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Martin Bahmann, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21