The Ojibwe

The Ojibwe are one of the largest tribal populations in North America. Their history is rich in tradition, with many cultural aspects still thriving today—despite brutal and devastating attempts by federal governments to colonize them.

After a nearly continuous fight for survival, their story is one of tragedy and conflict—but also triumph, perseverance, and incredible accomplishments.

Who Are They?

The Ojibwe are an Algonquian-speaking tribe that live in parts of the US and Canada. They call themselves "Anishinaabeg," which means the "True People" or the "Original People".

But that’s not typically what other people call them.

What Do Other People Refer To Them As?

Other Natives and some Europeans call them "Ojibwe" or "Chippewa," which meant "puckered up," probably because the Ojibwe traditionally wore moccasins with a puckered seam across the top.

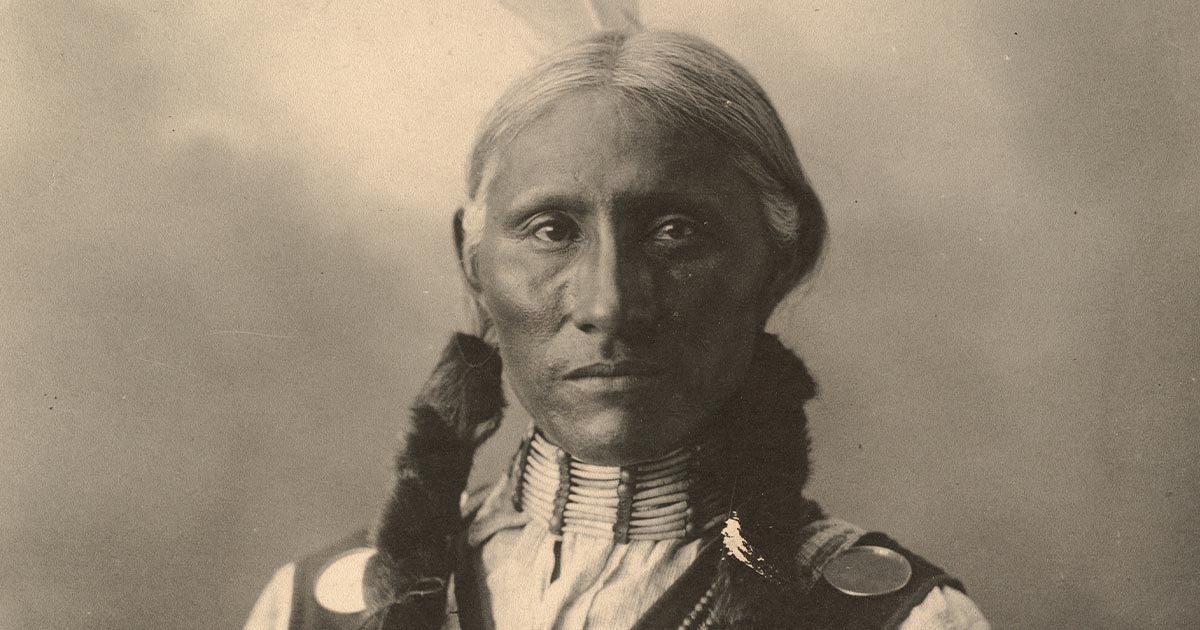

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

What Language Do They Speak?

The Ojibwe language is Anishinaabemowin (sometimes called Ojibwemowin), a branch of the Algonquian language family, and it’s quite beautiful and unique. However, many Ojibwe also speak English, especially the younger generations.

Sadly, the number of fluent speakers has declined sharply, with mostly only elders being fluent today.

There Are No Goodbyes

In their language, the Ojibwe have no specific word for “good-bye". The closest phrase would be “Giga-waabamin naagaj,” meaning “see you again".

It implies that spirit keeps us connected to everything, and is a more positive way of looking at things.

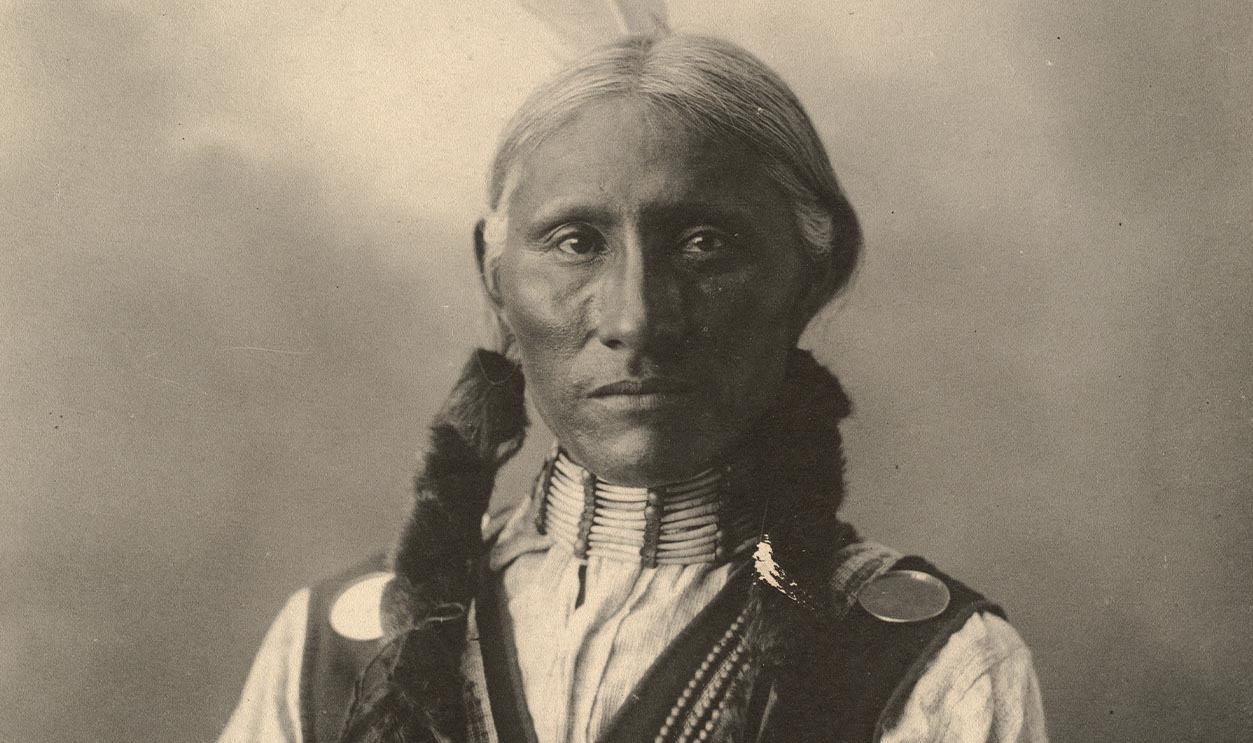

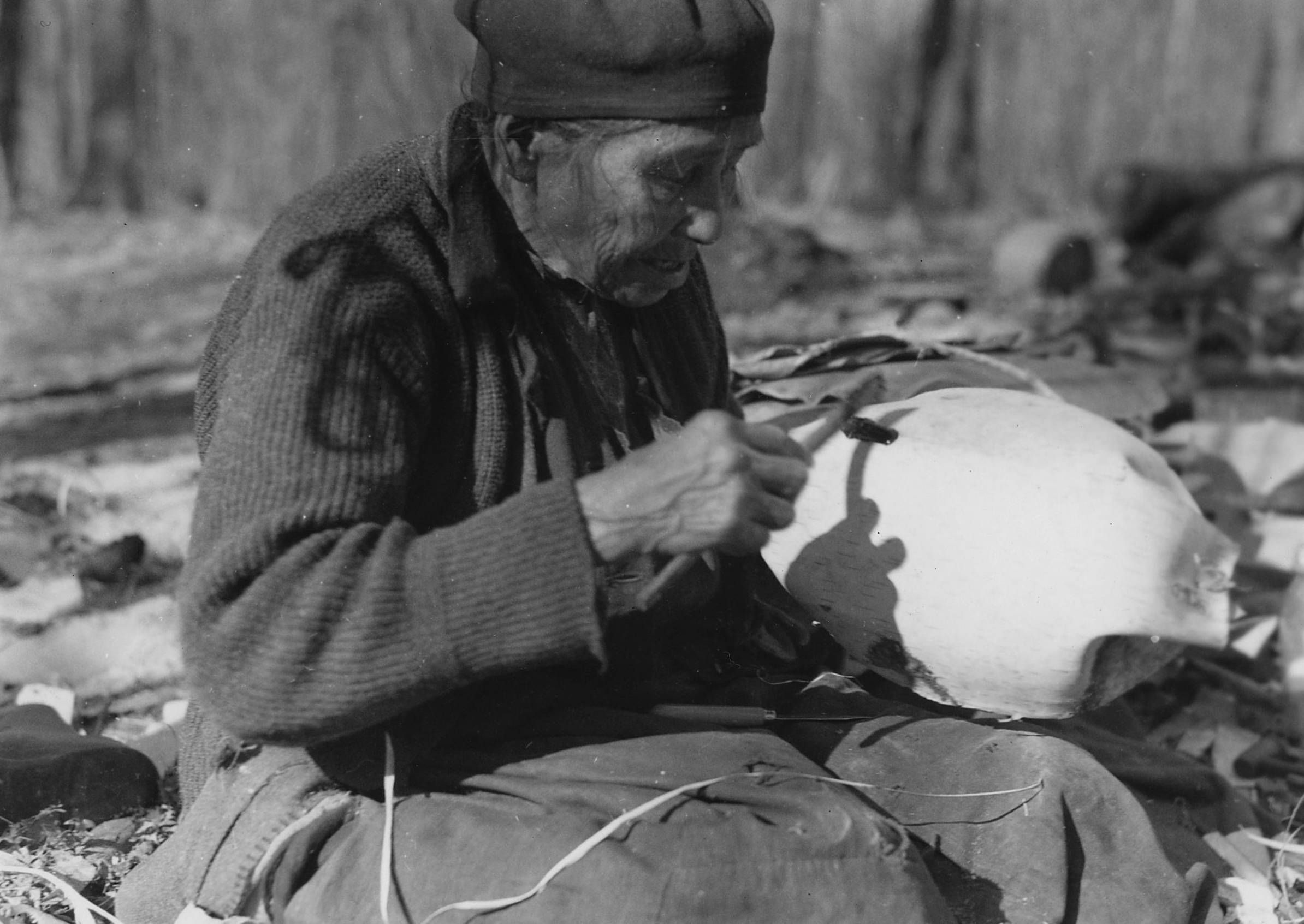

Minnesota Historical Center, Wikimedia Commons

Minnesota Historical Center, Wikimedia Commons

What Is Their Population?

The Ojibwe population is around 320,000 total—with close to 171,000 living in the US and about 160,000 in Canada.

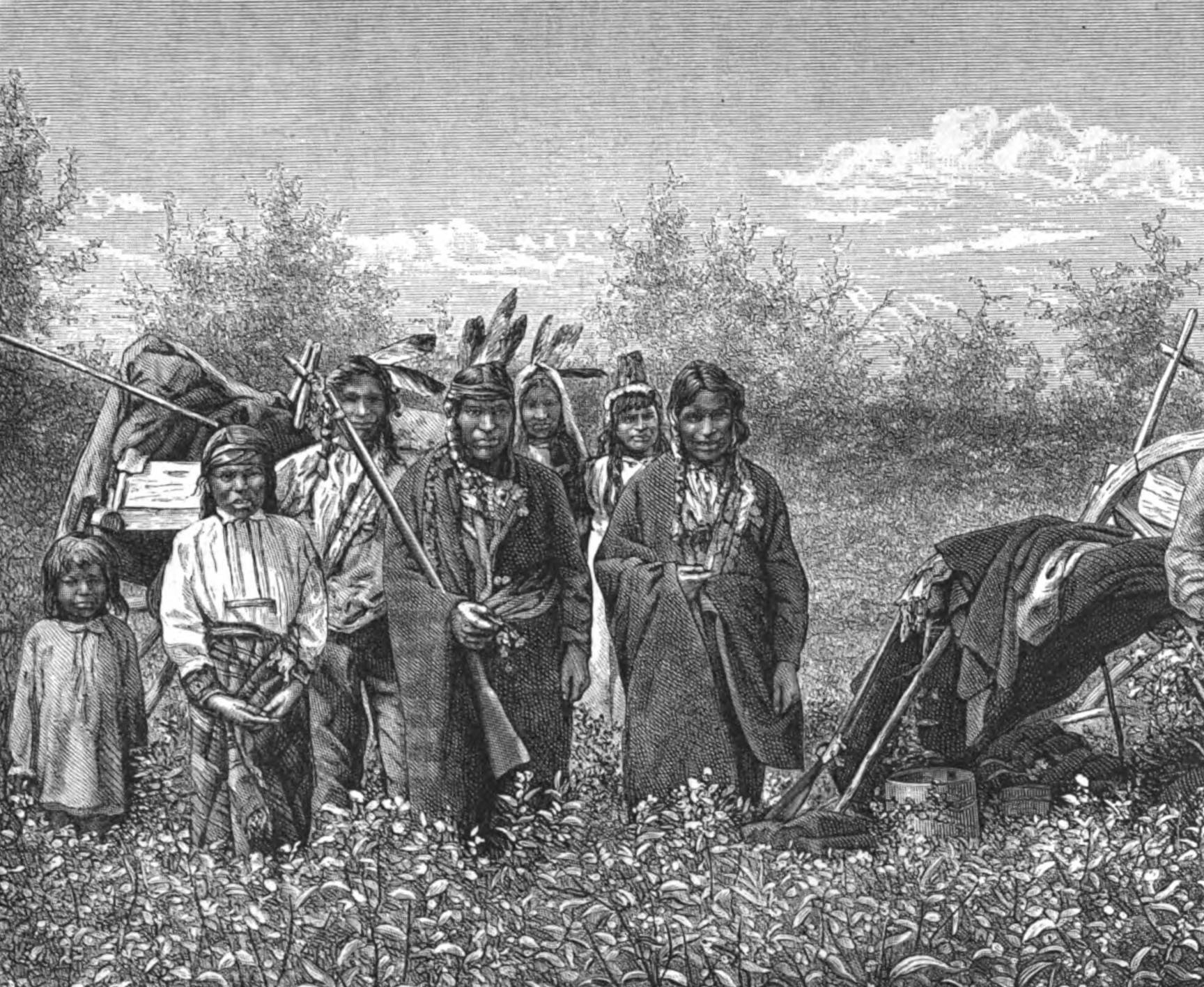

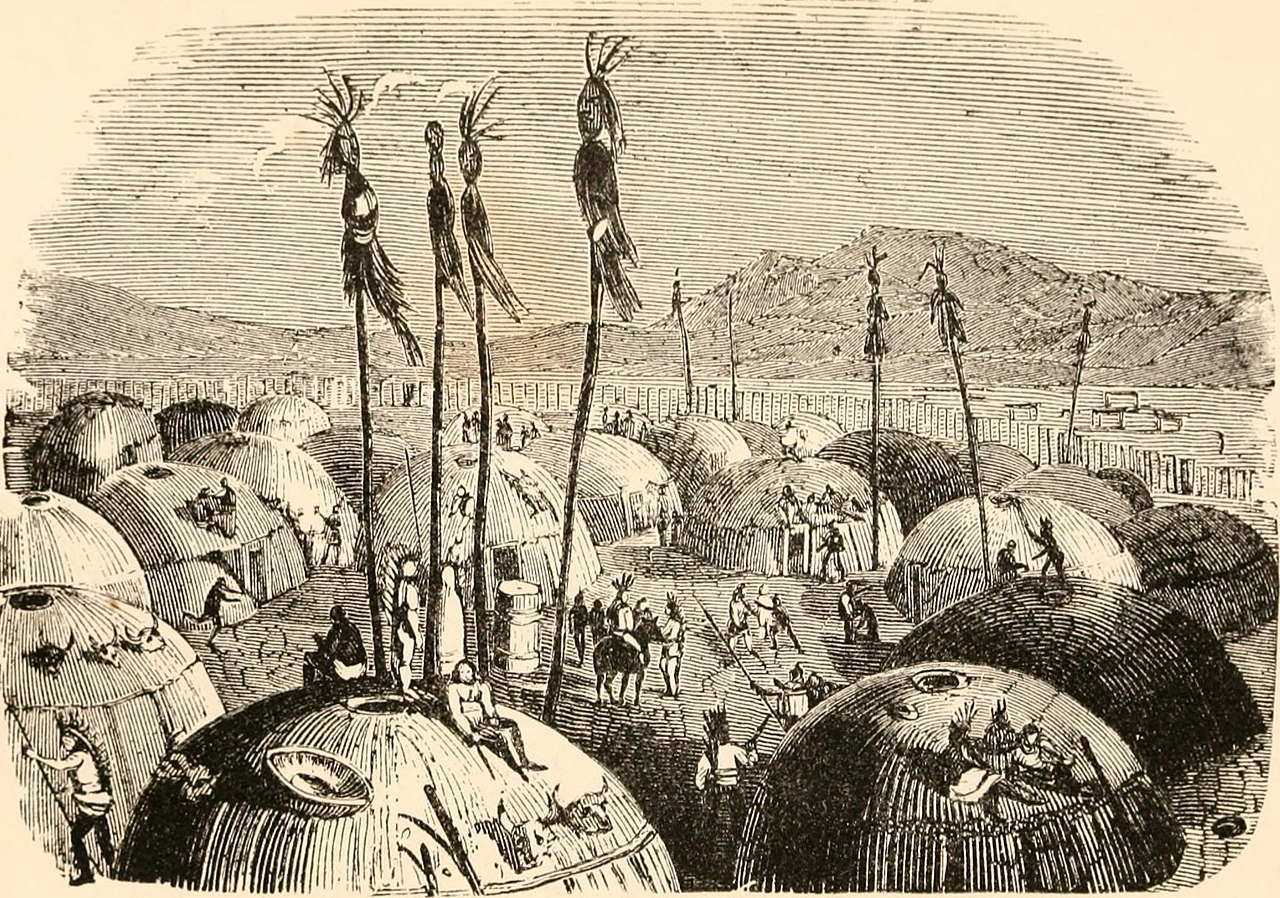

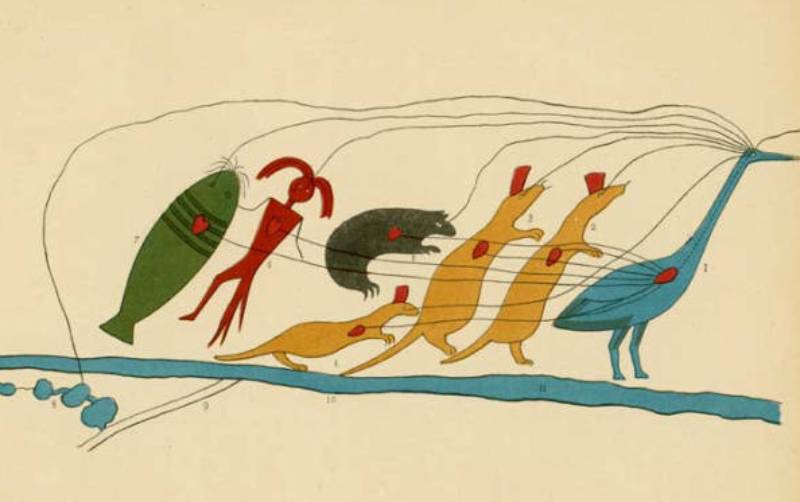

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Where Is Their territory?

According to Ojibwe oral history and from recordings in birch bark scrolls, the Ojibwe originated from the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River on the Atlantic coast of what is now Quebec.

It is believed that the Ojibwe occupied the territories around the Great Lakes as early as 1400, expanding westward until the 1600s. They were the largest and most powerful of all the tribes inhabiting the Great Lakes region of North America.

And their spiritual version of their history is nothing short of incredible.

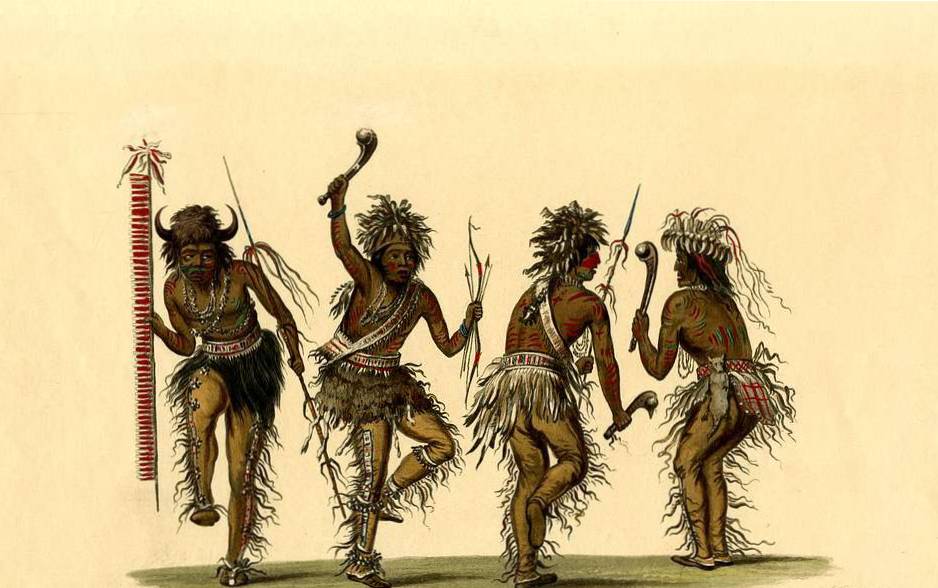

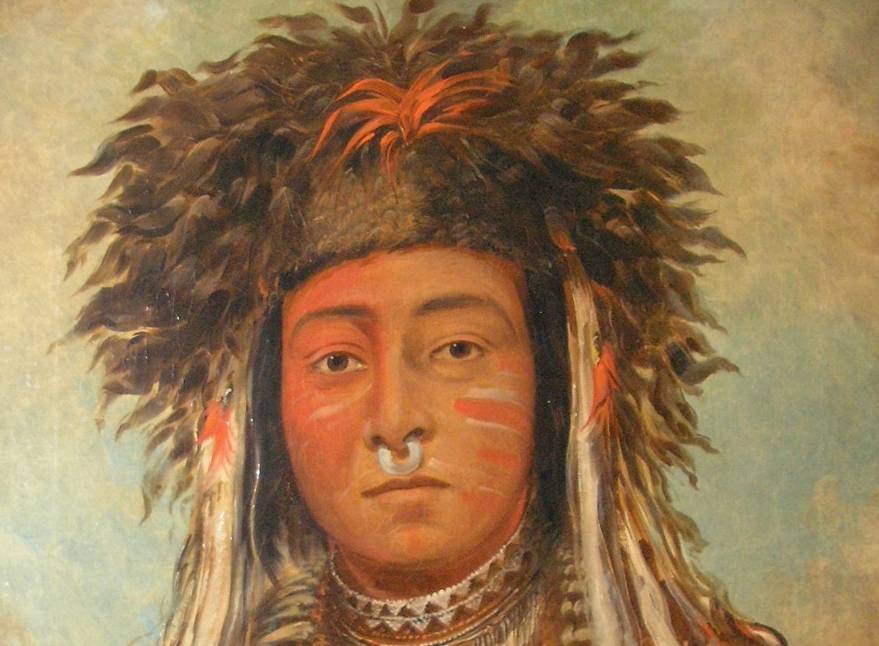

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

What Is Their Spiritual History?

Generations of oral history tells us that it all started when seven great miigis (cowrie shells) appeared to them in the Waabanakiing (Land of the Dawn, i.e., Eastern Land) to teach them the mide way of life.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

The Great Miigis

One of the miigis was too spiritually powerful and killed the people in the Waabanakiing when they were in its presence. The six others stayed to teach, while one returned into the ocean.

Before the six miigis returned to the ocean as well, they created something within the tribe that would make them stronger.

The Clans

The six miigis separated the group into five individual clans known as doodem or totem, symbolized by animals: the Waeaazisii (Bullhead), Baswenaazhi (Echo-maker, i.e., Crane), Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck), Nooke (Tender, i.e., Bear) and Moozoonsii (Little Moose).

Once the clans were established, the miigis left. But not long later, one of them returned with a stark warning.

The Warning

One of the miigis appeared in a vision during one of the clan members' vision quests to relate a prophecy. It said that if the Anishinaabeg did not move farther west, they would not be able to keep their traditional ways alive because of the many new “pale-skinned settlers” who would arrive soon in the east.

And they weren’t wrong.

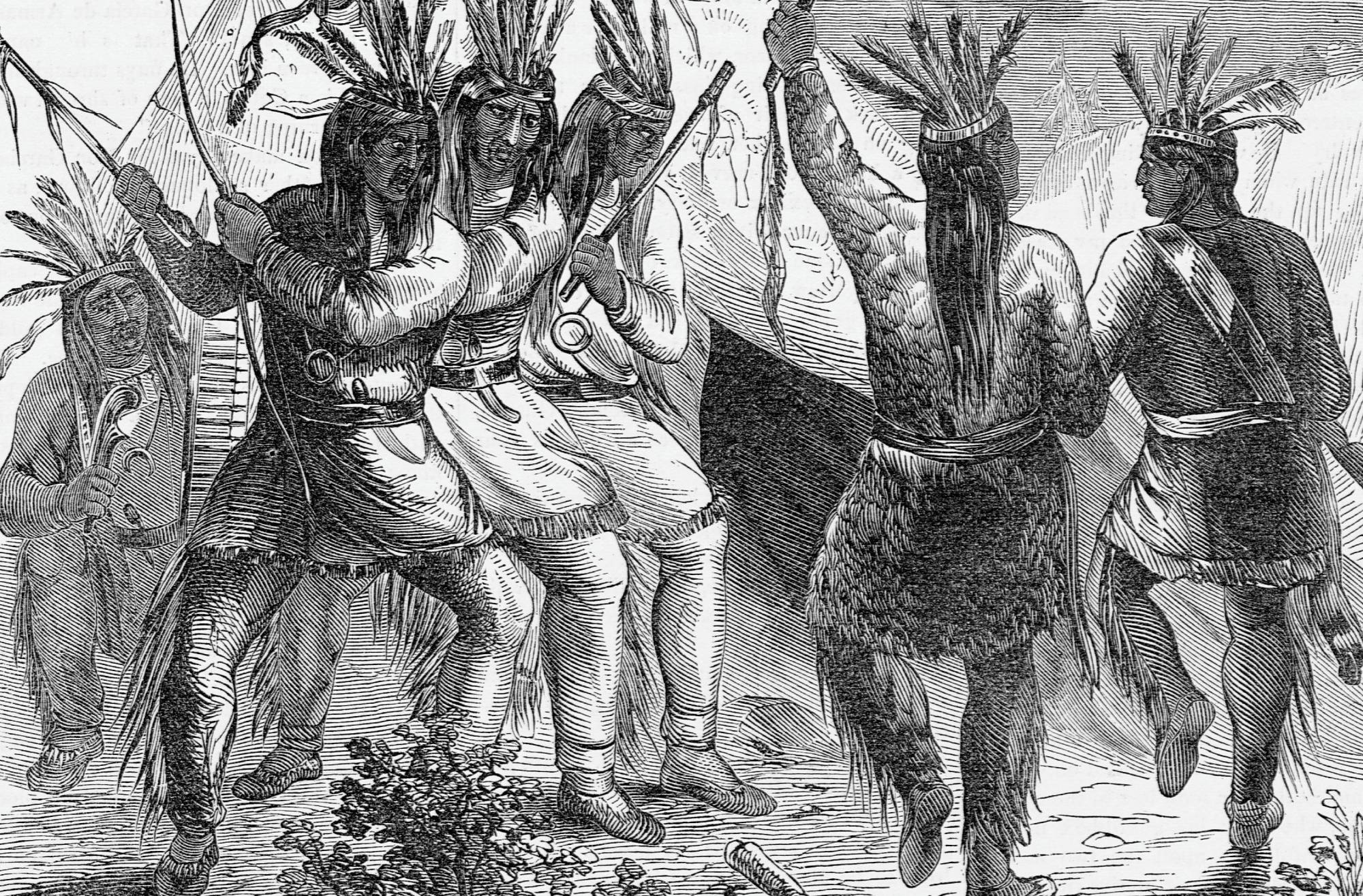

Frost, John, Wikimedia Commons

Frost, John, Wikimedia Commons

The Arrival Of The Settlers

As with many Native American tribes, White settlers eventually moved in on their territory and forcibly removed the Anishinaabeg from their land and onto reservations. This caused the Anishinaabeg to quickly migrate west and break into six groups—the Ojibwe being one of them.

Where Do They Live Today?

Today, in the US, the Ojibwe live mostly on reservations in parts of Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Montana. In Canada, they live from western Quebec to eastern British Columbia.

Their homeland still covers much of the Great Lakes region and northern plains, and extends up into the subarctic and throughout the northeastern woodlands.

Myotus, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Myotus, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

How Large Is Their Group Now?

The Ojibwe are the largest Native American group north of Mexico. They are one of the largest tribal populations among Native American peoples in the US, and in Canada, they are the second-largest First Nations population, surpassed only by the Cree.

Migration has played a key role in safeguarding their population over the years—but it is not without its downfalls.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

How Does Migration Change Their Culture?

While most Ojibwe inhabit large parts of the Great Lakes region, some have also migrated to the plains or areas further south. This has resulted in the need to adapt to different environmental conditions—which ultimately changes the way they dress, their art forms, and how they grow their food.

Traditionally, their varied ways of life are truly remarkable.

Ridpath, John Clark, Wikimedia Commons

Ridpath, John Clark, Wikimedia Commons

What Are They Known For?

The Ojibwe are known for many of their age-old traditions, such as their birchbark canoes, birchbark scrolls, mining and trade in copper, and their harvesting of wild rice and maple syrup.

And their Midewiwin Society is another major aspect.

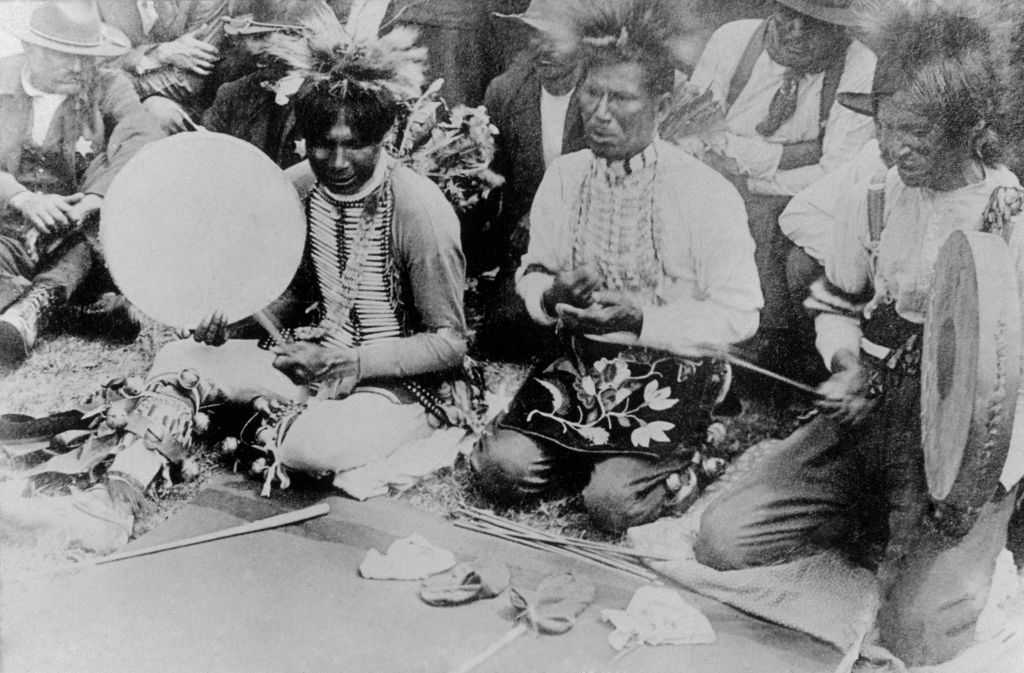

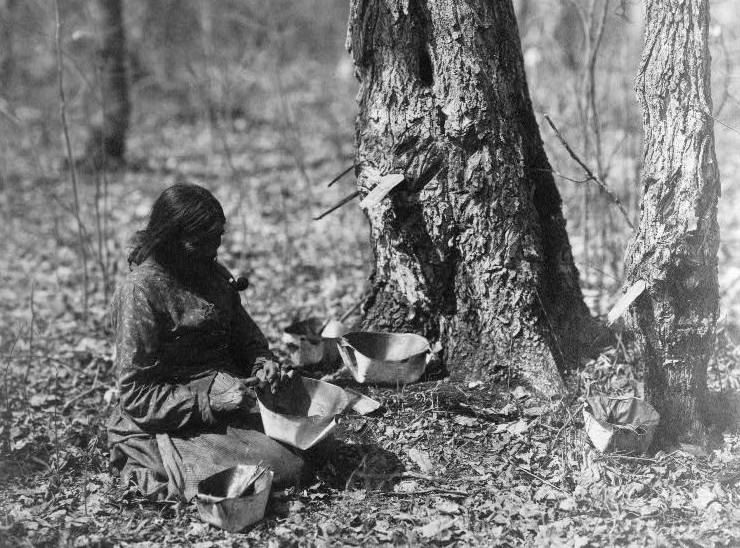

Reed, Roland, Wikimedia Commons

Reed, Roland, Wikimedia Commons

What Is The Midewiwin Society?

The Midewiwin (also known as the Grand Medicine Society) is a religious society made up of spiritual advisors and healers who not only take care of the sick people, but also communicate with the supernatural world in ways that benefit the tribe.

But that’s not all they do.

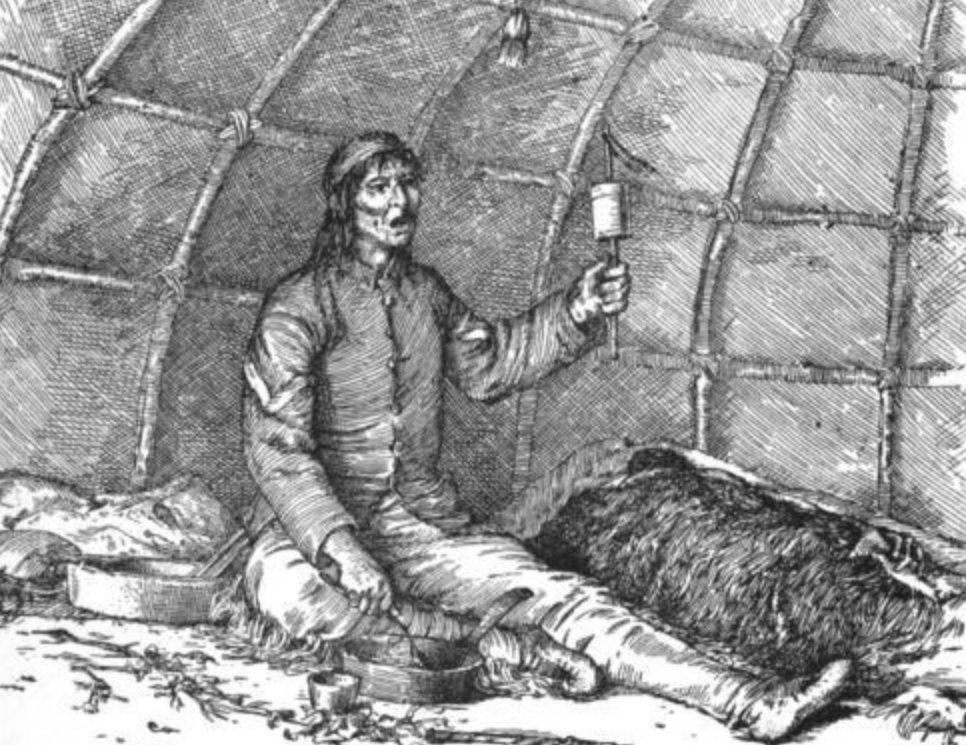

Bureau of Ethnology, Wikimedia Commons

Bureau of Ethnology, Wikimedia Commons

The Midewiwin Society

This society is well respected as the keeper of detailed and complex scrolls of events, oral history, songs, maps, and more.

Many traditional ceremonies include the use of medicine bundles—which are a collection of sacred objects.

Minnesota Historical Center, Wikimedia Commons

Minnesota Historical Center, Wikimedia Commons

What Is Sacred To The Ojibwe?

In Ojibwe religion, tobacco, cedar, sage, and sweetgrass are considered sacred plants. Sweetgrass and tobacco rituals are practiced routinely. And cedar and sweetgrass are deemed to have purifying properties.

The Ojibwe are extremely resourceful and knowledgeable. They are in tune with nature and are skilled at living off the land.

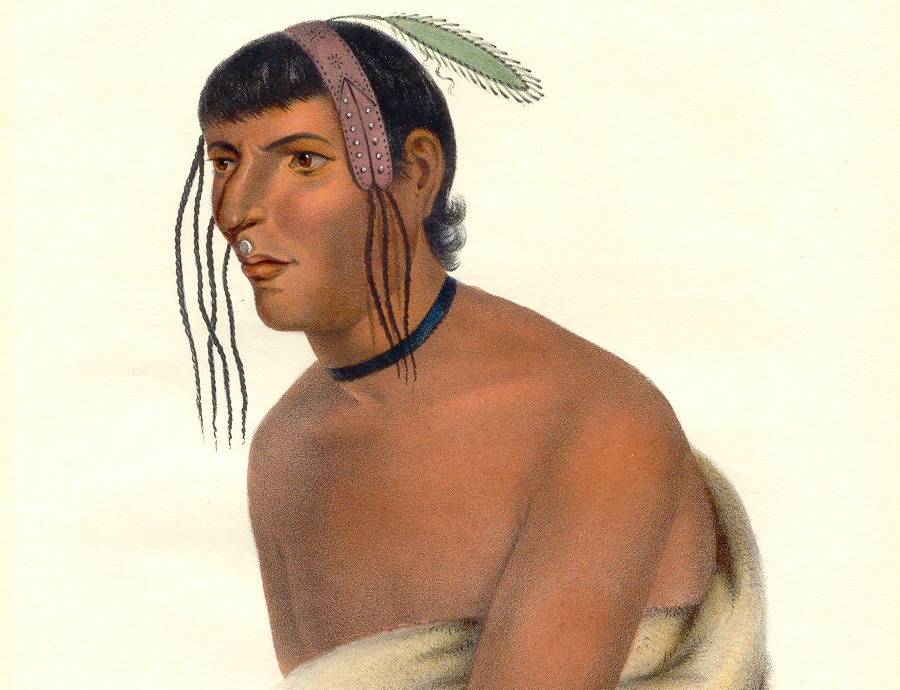

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

What Is Their Traditional Way Of Life?

Historically, the Ojibwe lived a settled (as opposed to nomadic) lifestyle, relying on fishing, hunting, and cultivation for food.

They used natural resources for pretty much everything, from food and clothing to shelter and tools.

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

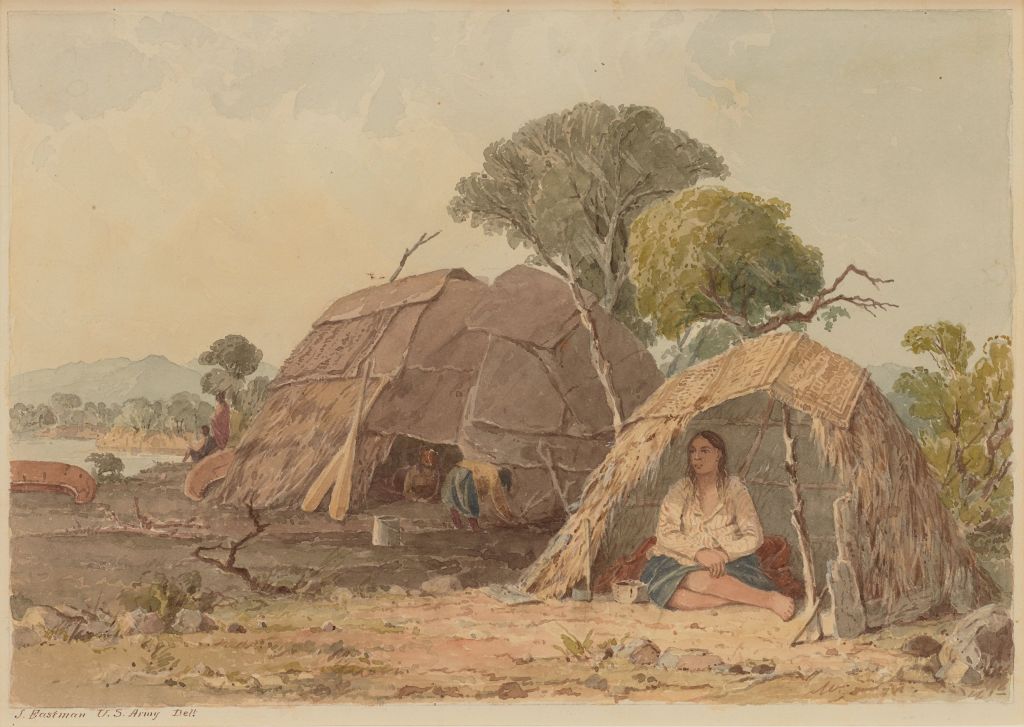

What Did Their Houses Look Like?

Traditionally, the Ojibwe dwelling has been the wiigiwaam (wigwam). It was either a waginogaan (domed-lodge) or a nasawa'ogaan (pointed-lodge), made of birch bark, juniper bark, and willow saplings.

However, in the modern era, they look a little different.

Eastman Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

Eastman Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

What Are Their Houses Like Today?

Today, most of the Ojibwe live in modern housing, but traditional structures are still used for special sites and events.

While their culture has evolved a lot over the years, not every aspect of it has been modernized.

Jubileejourney, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Jubileejourney, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

What Do They Eat?

The traditional Native American diet was seasonally dependent on fishing, hunting, foraging, and farming of produce and grains—particularly wild rice, beans, squash, corn, and potatoes.

They foraged for berries and cherries and they hunted for deer, beaver, moose, goose, duck, rabbit, and bear.

And they had one particular sweet treat that helped give variety to their dishes.

How Did They Use Maple Syrup?

The Ojibwe territories are full of sugar maple trees. So, they’ve always been (and still are) skilled maple syrup makers.

They use it in a variety of ways for cooking and baking, and have a traditional way of making granulated sugar with it as well.

Maple syrup is considered one of the sacred foods to the Ojibwe people.

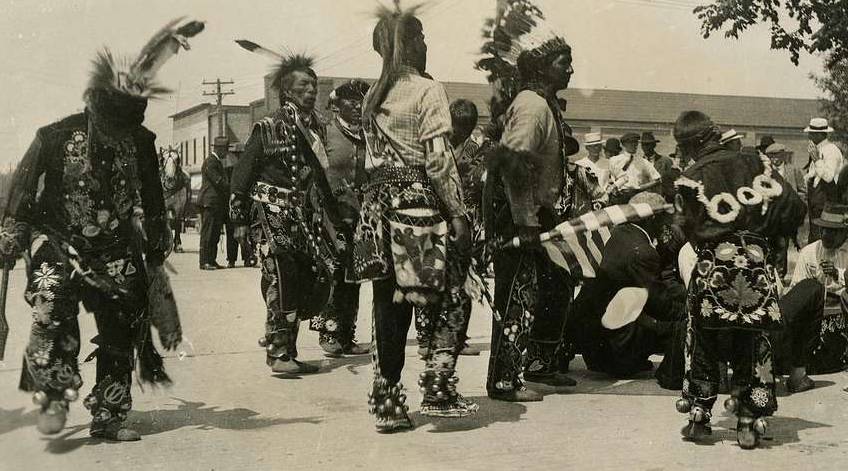

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

What Else Do They Still Practice Today?

The Ojibwe people still have totems or clans. Clan membership passes through the male lineage, from the father’s clan. And it’s still considered taboo to marry someone from the same clan.

What Is Their Clan System Like?

As mentioned, the Ojibwe clan system is patrilineal—from the father’s side. This means that children are considered born into the father’s clan. And in recent times, this system has caused some serious concerns for the Ojibwe people.

Roland W. Reed, Wikimedia Commons

Roland W. Reed, Wikimedia Commons

Fathered By Outsiders

After their migration was well under way, and many Native Americans began meshing with Europeans, there were children being born to French and English fathers. Sadly, these children were considered outside the clan and Ojibwe society (unless adopted by an Ojibwe male).

They were sometimes referred to as "White" because of their fathers, regardless if their mothers were Ojibwe, as they had no official place in the Ojibwe society.

And the complexity doesn’t stop there.

Eastman Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

Eastman Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

How Complex Is Their Kinship?

Kinship in Ojibwe clans includes the immediate family as well as extended family. Basically, a brother and sister will also consider their cousins their siblings, because they are all part of the same clan.

The social structure of women was also complex in regards to mothers and aunts. Even so, all clan members were seen as close family, and therefore, intermarriage was strictly forbidden.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

What Were Their Clans Like?

The five original clans (known as totems) were Bullhead, Crane, Duck, Bear, and Moose. The Crane totem was the most vocal among the Ojibwe, and the Bear was the largest—so large that it was sub-divided into body parts such as the head, the ribs, and the feet.

Each clan had certain responsibilities among the people—and they had to follow certain rules.

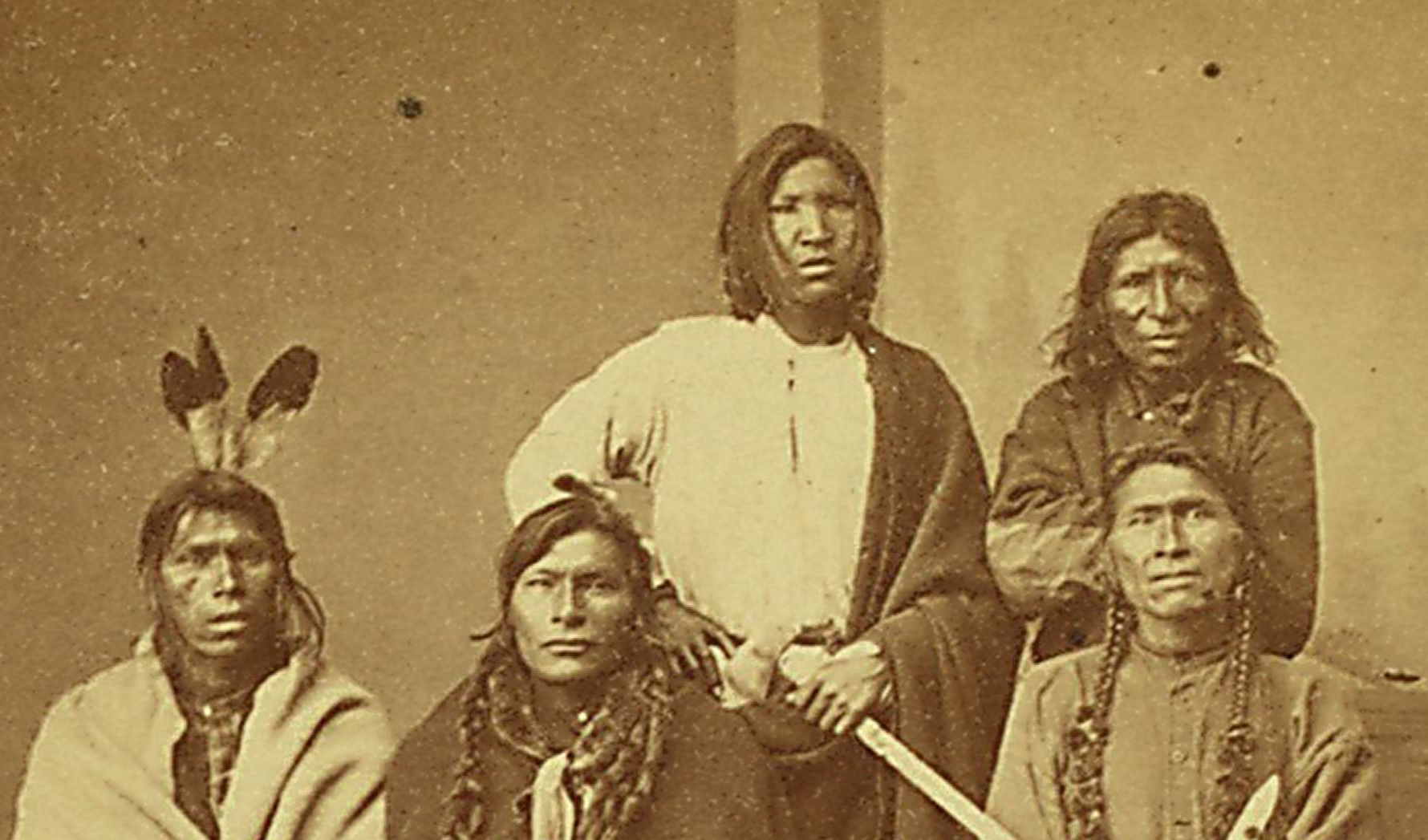

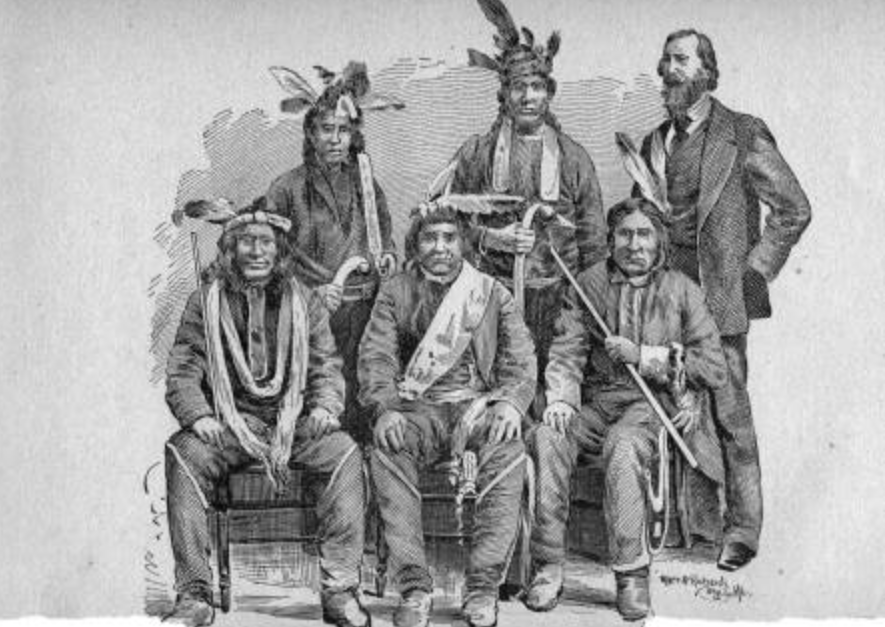

Bizhiki and other Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs, Wikimedia Commons

Bizhiki and other Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs, Wikimedia Commons

What Is Marriage Like?

For the Ojibwe people, they had to marry a spouse from a different clan. Intermarriage was not acceptable. And when it came time to choose a spouse, boys and girls had to take part in specific ceremonies and rituals in order to be considered “eligible” for marriage.

Roland W. Reed, Wikimedia Commons

Roland W. Reed, Wikimedia Commons

When Were Boys Eligible For Marriage?

Boys were eligible for marriage after doing a special ceremony called a vision quest. It involved four days of isolation in which they would fast, pray, and make offerings. The point of this quest was to find a guardian spirit to watch over them throughout their lives.

A vision quest could sometimes occur as early as age three or four, and were generally accomplished no later than puberty.

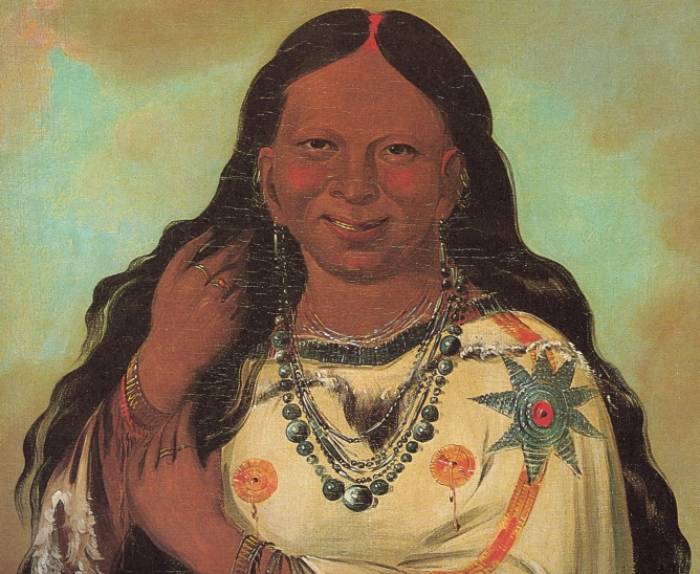

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

When Were Girls Eligible For Marriage?

Girls were eligible for marriage after they experienced their first menstrual cycle. During their cycle, they would be isolated away from the tribe in a separate hut.

Girls didn’t typically have a vision. If they did, it was considered a special blessing and the girl was thought to have healing powers.

Rituals are not the only unique part of an Ojibwe marriage, though.

Marriage Arrangement

Marriages would often be arranged by older family members. When a family arranged a marriage for their daughter, it was usually for economic stability—and she was given as a form of payment for service. Elders of the clan carefully watched all the unmarried girls, to ensure their purity.

A man could also choose the girl he wishes to marry—but he had to prove himself first.

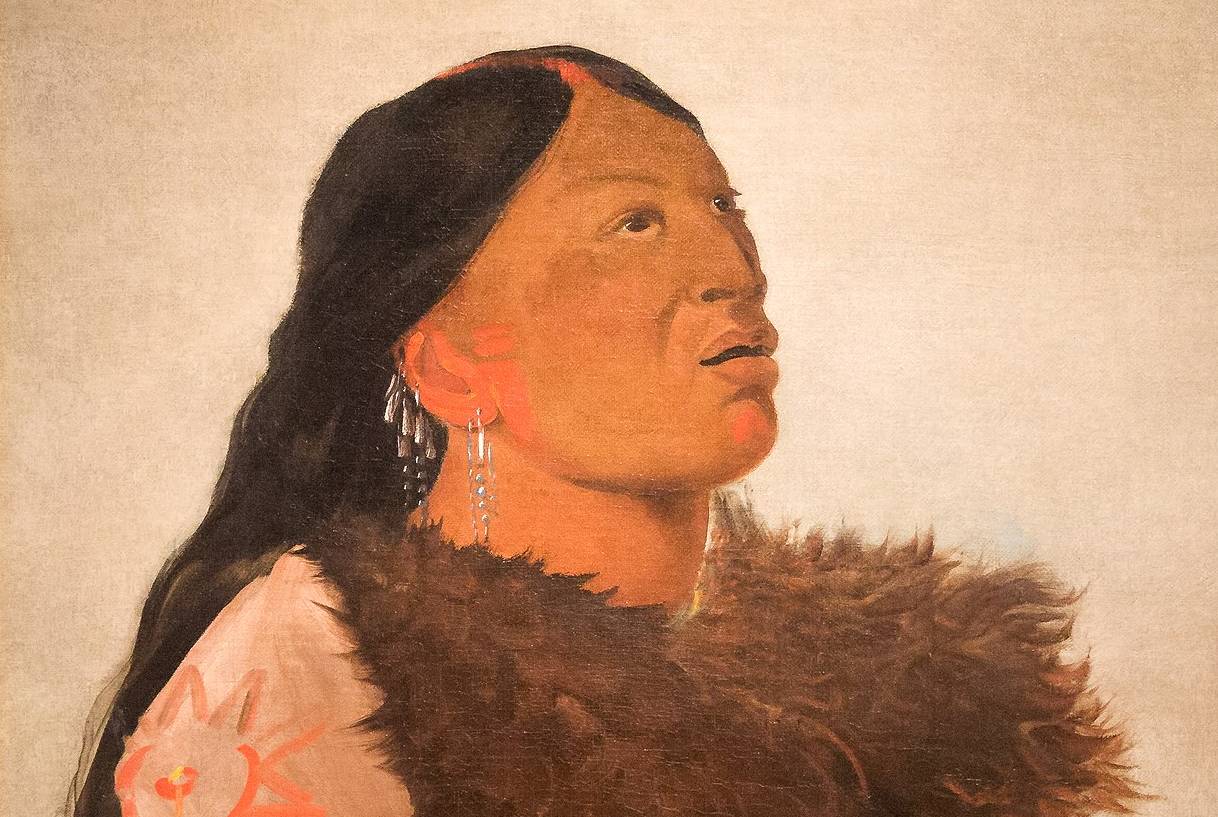

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

How Did A Man Prove His Worthiness Of A Bride?

If a man wanted to marry a girl, he had to hunt an animal and present it to her family—this was to prove that he could provide for his future bride. If the family approved, the girl was not allowed to turn down the proposal—even if she didn’t like the guy.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

What Was The Wedding Ceremony Like?

Traditional Ojibwe wedding ceremonies were extravagant. Women wore beautiful white dresses and white moccasins made from deer or elk skin and designed by the bride herself. Men wore black pants, a ribbon shirt, and moccasins.

And the event lasted three days—not including the days preparing in advance.

What Did They Do To Prepare For A Wedding?

The bride and groom had to choose four sponsors, who must be elders. The sponsors would promise to help the couple throughout their marriage, giving guidance and wisdom.

The bride was also required to bathe in a body of water, such as a river or lake. Bathing in the Earth’s natural waters is a symbolic act of being blessed by Mother Earth.

Charles Marion Russell, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Marion Russell, Wikimedia Commons

What Happened During The Three Days?

The first day of the wedding ceremony involved feasting. Foods would include fry bread, deer meat, squash, beans, three sisters soup, berries, and many desserts.

The second day involved visiting—where the couple visits family for personal blessings.

And the third day was called “The Giveaway,” where the official ceremony takes place and the bride is given away to her groom.

New York Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

New York Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

What Was Next For The Newlyweds?

After the wedding, the newlyweds would stay with the woman’s parents for about a year. During this time, if they wanted to start a family, they would build their own lodge. If they didn’t want to start a family, they could continue living with their parents.

And while there weren’t any honeymoons, the couple was given plenty of time alone.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

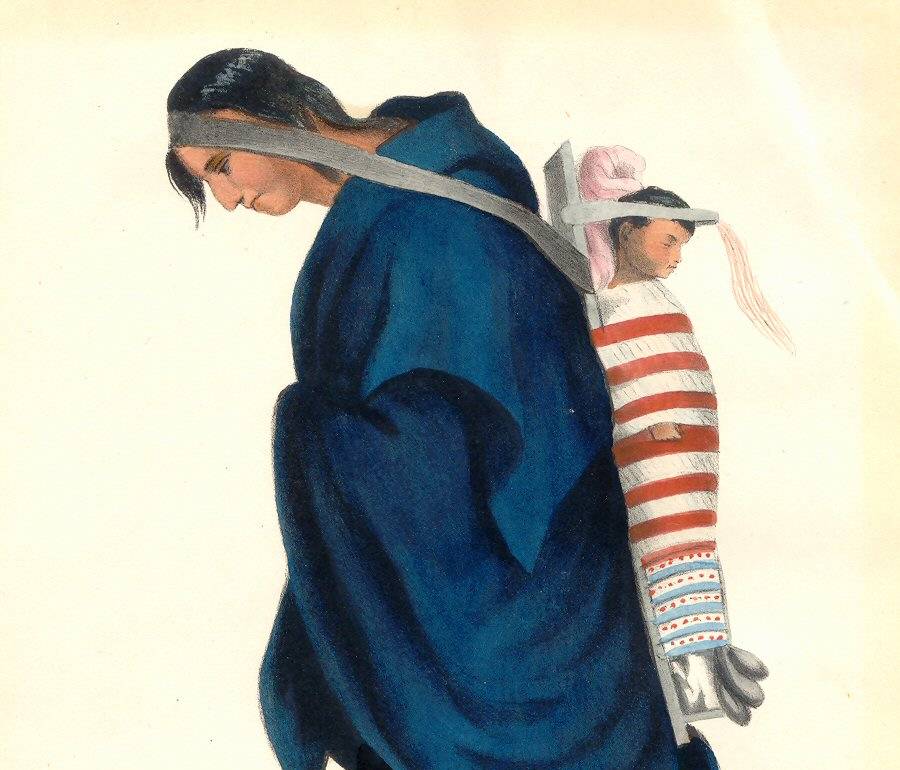

What Were The Women’s Roles Within A Marriage?

A woman is regarded as mature and responsible once she is married, regardless of her age. She becomes responsible for cooking, cleaning, making baskets, drying out meats, harvesting food, and foraging berries. She is also responsible for childcare and overall family welfare.

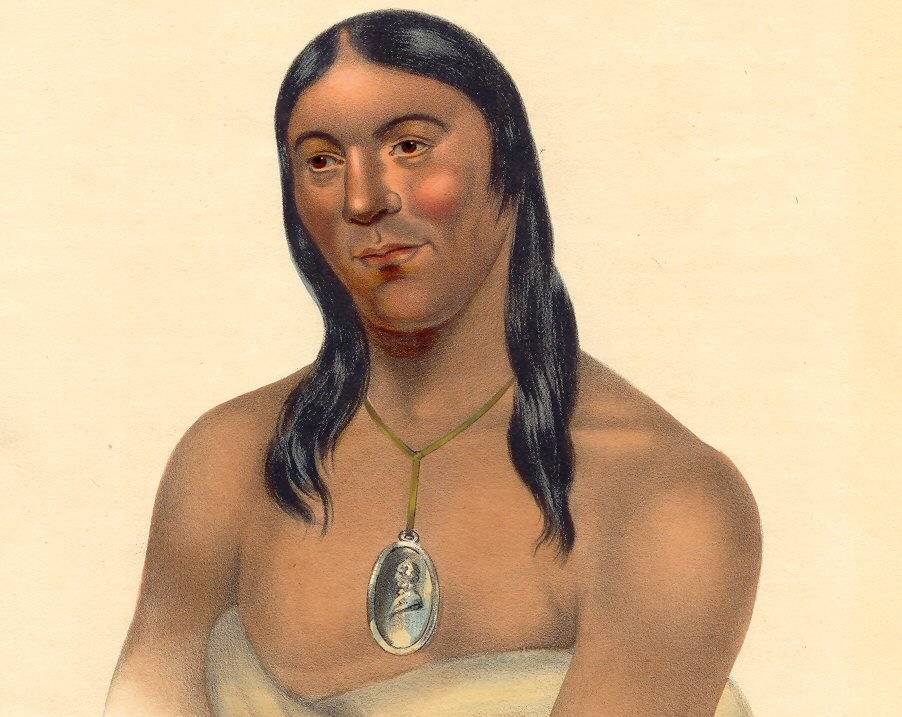

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

What Were The Men’s Roles Within A Marriage?

Once a man is married, he becomes responsible for providing a good livelihood for his new family. He is also responsible for hunting, providing supplies, and for keeping his wife happy.

Their traditional tribal views of marriage can often be seen as atypical—and for one specific reason.

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

Changing Tribal Expectations

In many Indigenous tribes around the world, there is great importance put on men, with women often being considered less-than.

However, Ojibwe marriages do not follow suit. They are actually fairly equal, and spouses are treated like respected partners—even in the cases where a bride was purchased, or when she lacked choice in the matter.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

What Was Divorce Like?

Traditionally, divorce was not allowed, regardless of what happened in the marriage. However, after 1450, it was more acceptable—but still fairly uncommon.

In order to get a divorce, the sacred marriage blanket had to be divided. But then the reason for the divorce would decide what’s next.

What Happened If Someone Was Disloyal In A Marriage?

If a man was disloyal in his marriage, traditionally, the women of the tribe would group together and viciously (and publicly) whip him.

If a woman was disloyal, her possessions were taken away and she would be publicly shamed and snubbed by the tribe—which would ultimately brand her with a symbolic scarlet letter.

Were They Allowed To Remarry After A Divorce?

Yes, a person could remarry after a divorce, though not many men desired a previously divorced woman. If a spouse had died, they could remarry—but only after they had mourned for a year.

National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

What were their traditional funeral practices?

In Ojibwe tradition, the first thing to do after a death is bury the body as soon as possible—the same day, or the next day at least. Doing this allows the spirit to journey to its “place of joy and happiness”.

This particular place is called Gaagige Minawaanigozigiwining.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

The Journey

The journey to Gaagige Minawaanigozigiwining, the land of happiness where the dead reside, takes four days—which is why it's important to get them on their way as soon as possible.

In order for the spirit to embark on its journey, the body has to be prepared first.

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

Preparing The Body

As you can imagine, this process must happen quickly, but it also has to be done properly. If the body cannot be buried the same day, guests and medicine men had to stay with the body and the family to help them mourn, while also singing songs and dancing throughout the night.

Once the preparations were complete, the body would be placed in a rather interesting position.

Burial Mounds

When a body was ready to be buried, it would be placed in an inflexed position with their knees towards their chest. They then bury the body in a short grave and top it with a burial mound made of earth and stone. Many would also erect a jiibegamig or a "spirit-house" over each mound.

A historical burial mound would typically have a wooden marker, inscribed with the person’s clan sign.

After The Burial

After the burial, a fire is lit (and kept lit) and food is placed at the burial site to help nourish the spirit on its four-day journey. The food will be refreshed daily for the full four days.

But it doesn’t end there.

The Reception

Much like modern-day funeral practices, the family still gets together to celebrate the life lost. Usually, this takes place after the four days, to celebrate the successful journey of their loved one.

A large feast is held by the medicine man, and items are then exchanged.

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

What Items Are Exchanged At A Funeral?

The deceased person’s belongings are given away to other tribal members and family. The people chosen to receive those belongings are then required to trade in a new piece of clothing—which would be turned into a bundle.

This bundle of new clothing, along with a large prepared meal, is then given to the closest relative—but they don’t keep it for themselves.

Underwood Archives, Getty Images

Underwood Archives, Getty Images

What Did They Do With The New Clothing?

The hot meal and new clothes were not actually a gift to the closest relative. That person then divides the new clothing and gives it to other people they feel are worthy.

Aside from the traditional burial mounds, present-day practices follow the same spiritual beliefs and rituals, right down to the four-day journey and the exchange of possessions.

What Other Ceremonies Do They Have?

Weddings and funerals aren’t the only remarkable ceremonies the Ojibwe have. In fact, many of their traditional ceremonies are still held today. These ceremonies include fasting vision quests, initiations or rite of passage ceremonies, the Shaking Tent ceremony, Sunrise ceremony, and the most well-known: the Pow Wow.

Each of these holds religious significance.

Spiritual Symbols

These ceremonies include different spiritual symbols, such as the eagle or other icons, and are a gathering of the tribe often directed towards gaining more spiritual insight. And while those ceremonies are a group effort, much of the focus is on individual spiritual growth—which includes something very important.

The Significance Of Dreams

One of the focal points of the Ojibwe religion is gaining insight through dreams or visions. Traditionally, they would do this through rituals that were dedicated to acquire these dreams.

It was also important for them to take part in fasting—which is commonly used to enhance their ability to access different dreams or visions.

These vision quests were also marked by a specific symbol that is still widely popular today.

The Dream Catcher

Dream catchers are handmade objects made from twine, leather, feathers, and beads. They are used to catch good dreams.

Traditionally, a tribe would also have a “dreamer” set in place. A dreamer was a tribal visionary who had access to dreams of strong importance and significance; oftentimes these dreams were prophetic and used to foretell some oncoming danger.

Sometimes, a particular lodge was used to further access visions.

Sweat Lodges

Sweat lodges played a significant role in bringing dreams, as well as healing. If using a sweat lodge to access a dream or vision, water would be poured over hot rocks to produce steam and all of the doors were closed off—similar to a sauna. Sometimes, birch or pine was added to the rocks to enhance the experience.

And while there were many spiritual components traditionally, the Ojibwe religion has changed over the years.

D. Gordon E. Robertson, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

D. Gordon E. Robertson, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

What Religion Are They Today?

Sadly, with the arrival of Europeans, many of the Ojibwe tribes slowly lost their traditional religion and followed the path of Christianity instead. Today, most modern Ojibwe are Roman Catholics or Protestant Episcopalians.

Though some stay strong in holding true to their heritage.

How Do They Mesh Their Spiritual Beliefs With New Religions?

Even though many Ojibwe follow other religions today, they still hold tight to many of their traditional beliefs. This is seen in their marriage and funeral practices, as well as in their vast medicinal practices.

Wpwatchdog, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Wpwatchdog, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

How Did They Discover Medicinal Plants?

For as far back as they go, the Ojibwe have been extremely skilled at identifying all things from nature. By observing other living things, they are able to distinguish the good and bad offerings in nature—and find countless uses for the abundance of natural resources at their fingertips.

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

Observing The Beavers

For example, after seeing muskrat and beavers store the corms of Sagittaria cuneata (a flowering water plant also called arum leaf arrowhead) in large caches, the Ojibwe learned to recognize and appropriate the plant.

The plant is regularly used by Native American tribes for treating indigestion, but also as a food—eaten boiled, fresh, dried, or candied with maple sugar.

But that’s not the only natural medicine they’ve found.

Cheryl Reynolds, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Cheryl Reynolds, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

What Else Do They Use Plants For?

The Ojibwe use many different plants for various medicinal uses, including: treating urinary problems, treating infections and gangrene, inducing vomiting, treating pain and discomfort, healing from childbirth, aiding in sleep, managing headaches and colds, and so much more.

Some plants are steeped in a tea, others are burned and inhaled, and some are cooked and prepared into ointments.

They also use plants for other things too.

SriMesh, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

SriMesh, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mind Altering Substances

The Ojibwe use plants and other natural goods to enhance certain experiences, such as during rituals and ceremonies. Some plants give the user psychic abilities, or help take the user into a relaxed state that allows their spirit to communicate in other ways.

And then there are some plants they smoke in pipes to apparently attract game.

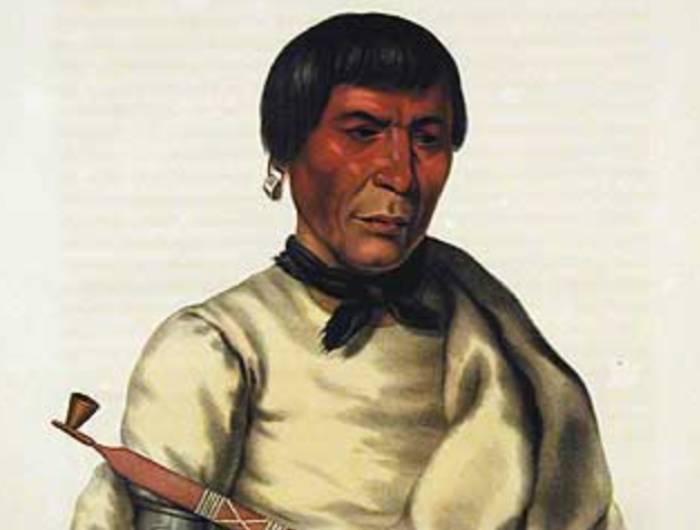

Thomas Loraine McKenney (1785-1859), Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Loraine McKenney (1785-1859), Wikimedia Commons

Fighting For Survival

These traditions and practices have survived thousands of years—but it hasn’t exactly been an easy road. As with many North American tribes, the Ojibwe had to fight to save their culture—and their lives.

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

First Contact With Europeans

The first historical mention of the Ojibwe dates back to 1640 by French missionaries who made friends with the Ojibwe people, giving them access to guns and European goods—which allowed them to dominate their traditional enemies, the Lakota and Fox.

Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images

Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images

Taking Control

Over the years, the Ojibwe fought countless land battles with their enemies, and by the end of the 18th century, they controlled nearly all of present-day Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and Minnesota, including most of the Red River area.

They also controlled the entire northern shores of lakes Huron and Superior on the Canadian side, extending westward to the Turtle Mountains of North Dakota.

But their victories didn’t last forever.

Blurred Lines

While “peace and friendship” treaties existed between Ojibwe and European settlers, the understanding of the treaties differed greatly between the parties. The US and Canadian governments viewed land as a commodity of value that could be freely bought, owned, and sold.

But the Ojibwe saw land as a fully shared resource, along with air, water, and sunlight. This understandably became a problem.

Whitney Studio, Wikimedia Commons

Whitney Studio, Wikimedia Commons

When One War Led To Another

The Ojibwe had a long-standing alliance with the French, and so they sided with them during the Seven Years’ War. But when they lost, France was forced to cede its land claims to Britain—which then resulted in the Pontiac’s War, where various Native American tribes fought to drive British soldiers out of the region.

Ultimately though, they lost and had to adjust to British colonial rule—and eventually, they allied with the enemy.

Capt. Hervey Smyth, Wikimedia Commons

Capt. Hervey Smyth, Wikimedia Commons

The War Of 1812

Next up was the War of 1812, where the Ojibwe allied with British forces against the United States—hoping a victory would protect them from American settlers. They fought hard—but they also fought smart.

They Knew Their Worth

The Ojibwe saw themselves as allies and not subordinates. Various tribes fighting with United States forces provided them with their "most effective light troops" while the British needed Indigenous allies to compensate for their numerical inferiority.

But they knew when their help would do more harm than good.

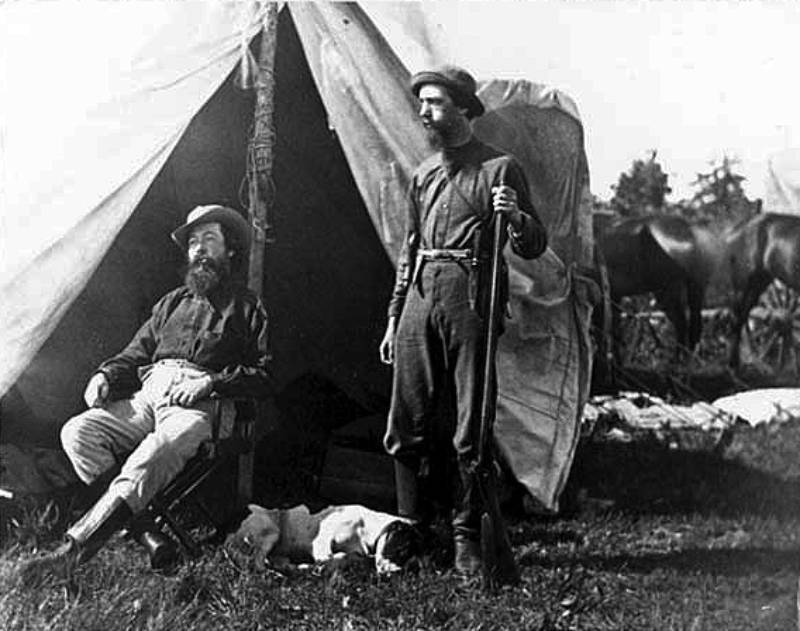

Smith Collection/Gado, Getty Images

Smith Collection/Gado, Getty Images

How Did They Approach Battle?

The Ojibwe leaders sought to fight only under favorable conditions and would avoid any battle that promised heavy losses—doing what they thought was best for their tribes. They saw no issue with withdrawing if it was needed to save casualties.

With their knowledge of the terrain and the ability to march 50 miles a day, their help was invaluable.

What Weapons Did They Use?

Their main weapons were a mixture of muskets, rifles, bows, tomahawks, knives, and swords as well as clubs and other melee weapons, which sometimes had the advantage of being quieter than guns.

They always sought to surround an enemy, where possible, to avoid being surrounded themselves. They also made effective use of the terrain.

What Was The Outcome?

During the war, many battles were won and many were lost, but in the end, the Native Americans in North America were still not safe from encroachment.

While some treaties existed to keep peace, the ultimate goal of US officials was to essentially remove them from their land—and they didn’t give up.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

They Resisted

In the years following the war, the US government tried to forcibly remove all the Ojibwe to Minnesota, west of the Mississippi river—but they resisted, and violent confrontations took place.

The Sandy Lake Tragedy

By the late 1840s, government officials in Washington began efforts to remove the Lake Superior Ojibwe people from their homeland. Officials had treaty payments changed to a place in Minnesota—which would require a journey of 150 miles by canoe and on foot.

The result was horrifying.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers from USA, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers from USA, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

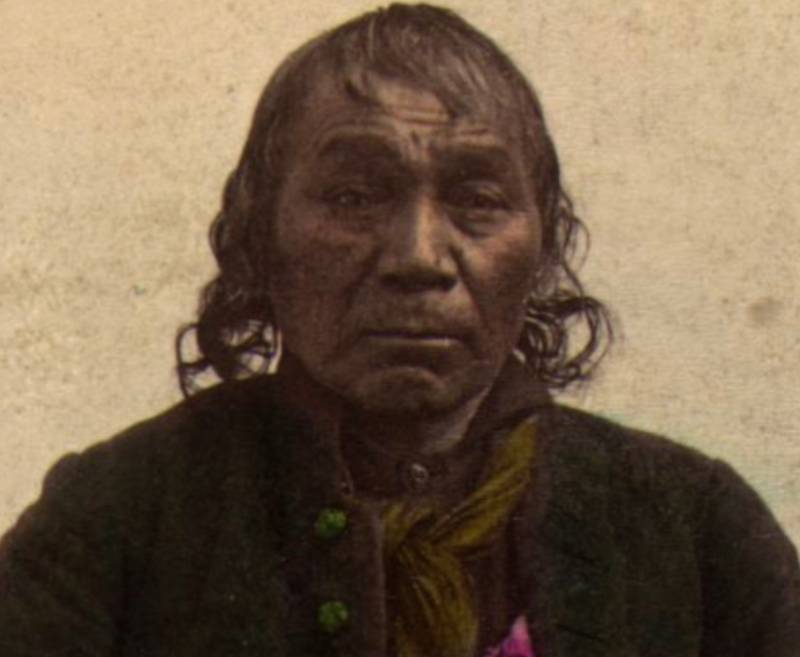

The Sandy Lake Tragedy

As a result of the treacherous journey to Minnesota, hundreds of Ojibwe people died. With delayed payments, tainted food, disease, and the onset of winter, the Ojibwe people didn’t stand a chance. They were unable to provide for themselves and were not given anything to supplement. They were cold, hungry, sick, and hurt—and over 400 people perished as a result.

But when the government tried to do it again with another group of Ojibwe, the chief stepped in.

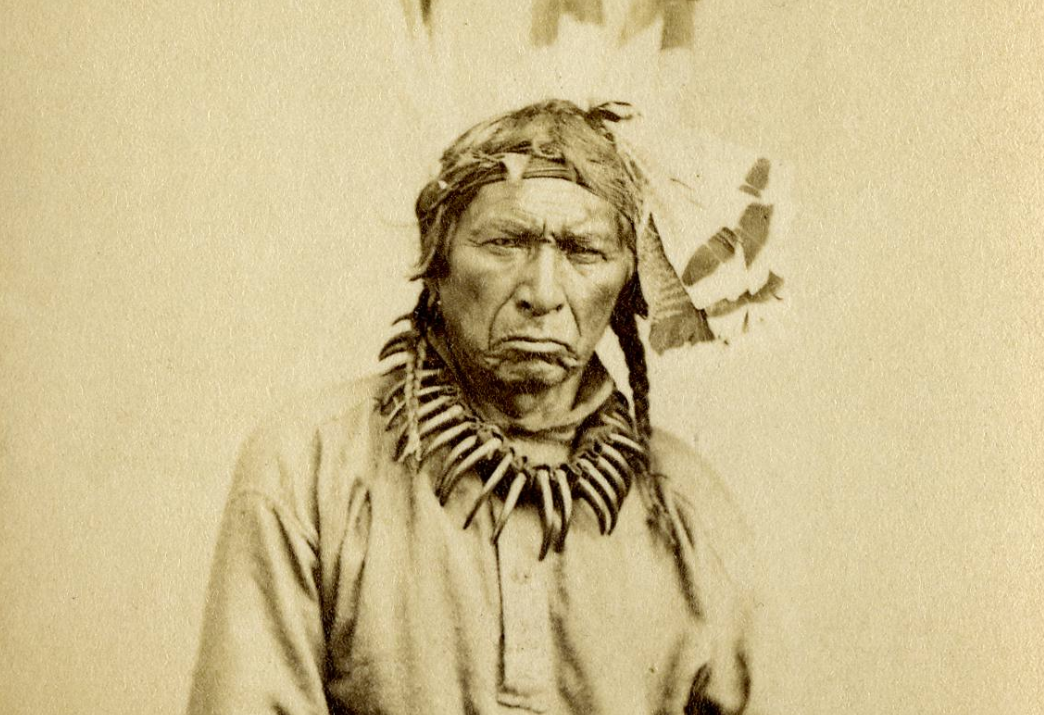

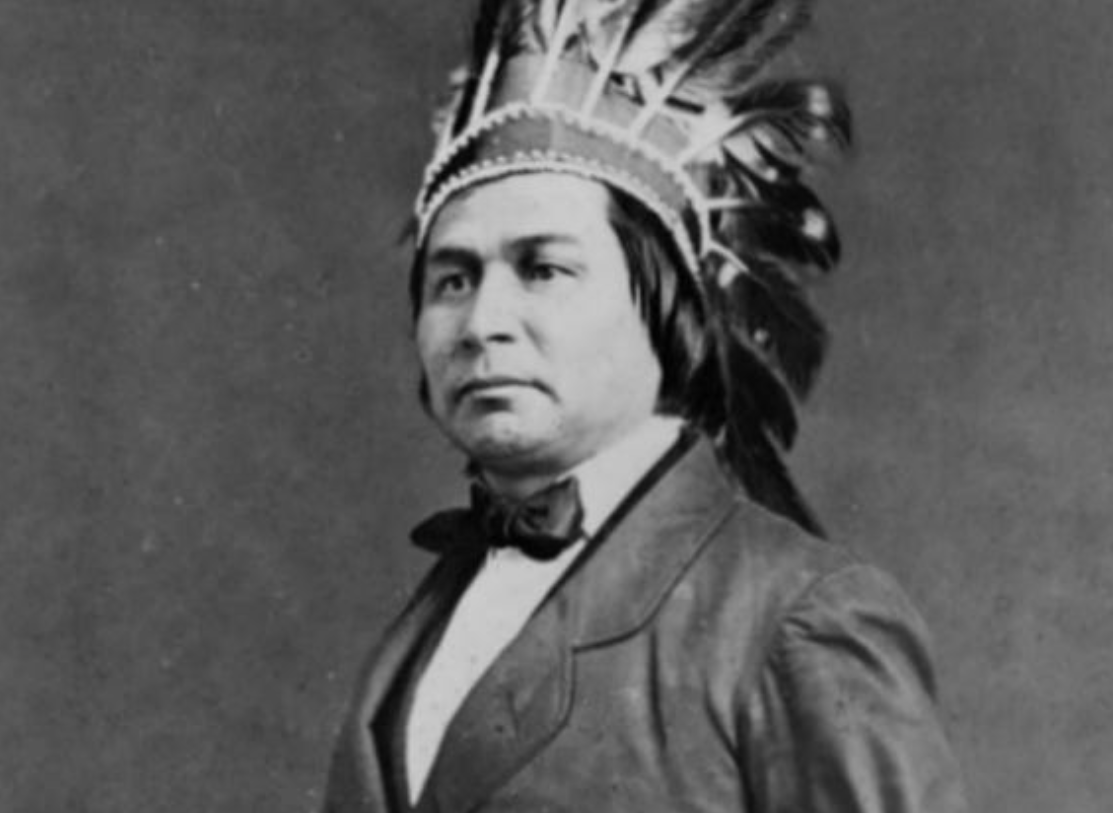

Chief Buffalo

Kechewaishke (Chief Buffalo), principal chief of the Lake Superior Chippewa, was determined to do whatever was necessary to protect his people. He and a handful of his men made the long journey to Washington, to personally address the president—and made one specific demand.

Benjamin Armstrong and Thos. Wentworth, Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin Armstrong and Thos. Wentworth, Wikimedia Commons

How Did The President Respond?

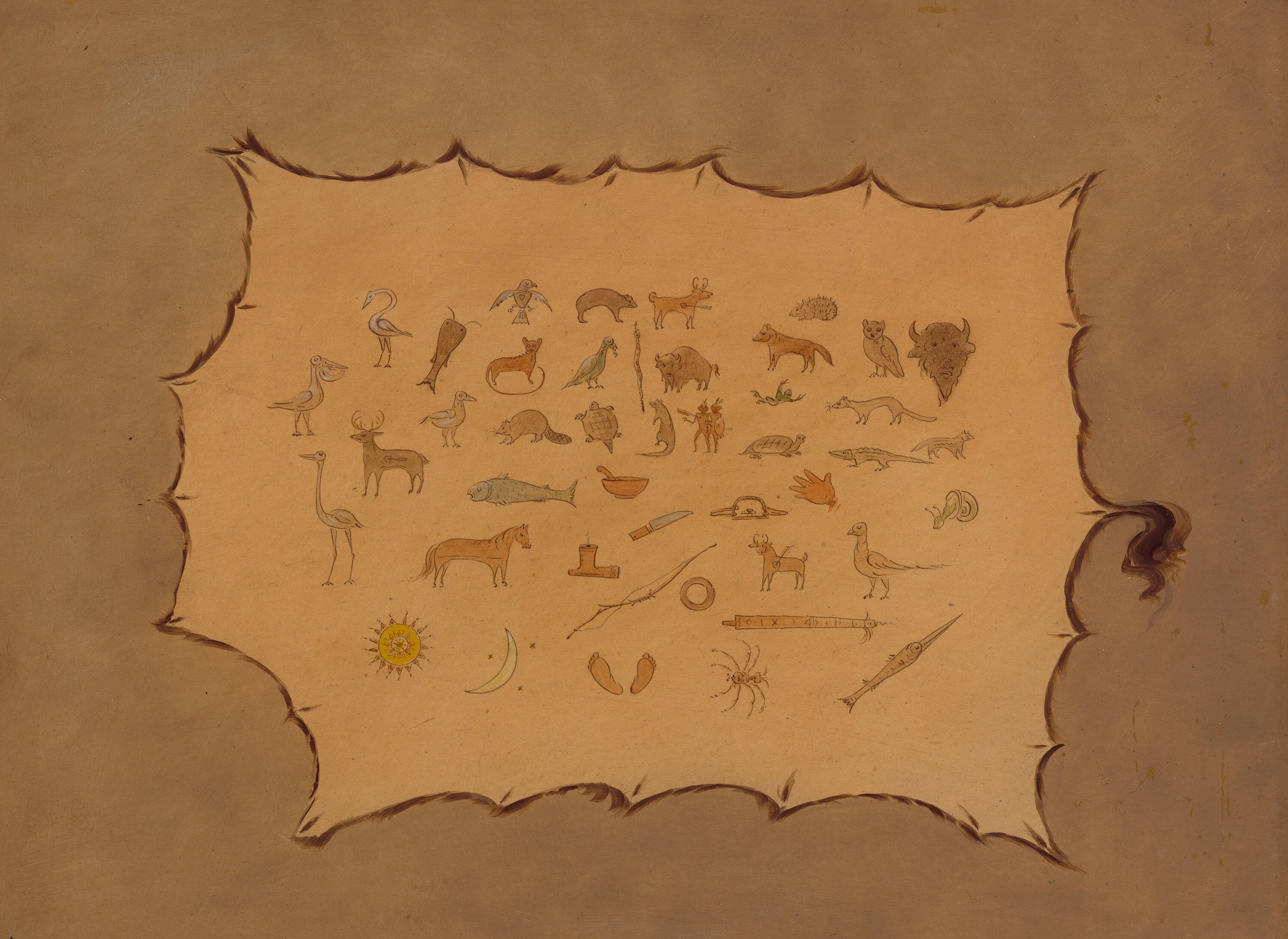

Chief Buffalo showed up in Washington with a petition (a pictograph drawn on a birch bark scroll) along with a long list of public supporters. The outrage that occurred after the Sandy Lake Tragedy increased Ojibwe resistance to removal, and the bands effectively gained widespread public support.

With all this, President Fillmore was backed into a corner.

Mathew Benjamin Brady, Wikimedia Commons

Mathew Benjamin Brady, Wikimedia Commons

What Did The President Decide?

After realizing just how much of the American public was against the Ojibwe removal, President Fillmore announced that the removal order would be canceled, and that another treaty would establish permanent reservations for the Ojibwe in Wisconsin.

And after this treaty, many others followed. But that didn’t mean everything would work out.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Life After Reservations

Once the reservations were created, the Ojibwe were unable to sustain themselves by hunting and gathering, and many Ojibwe men worked as lumberjacks for White-owned companies. While this created an income for Ojibwe people, it also led to further land loss.

SMU Central University Libraries, Wikimedia Commons

SMU Central University Libraries, Wikimedia Commons

How Did They Lose More Land?

In 1887, the Dawes Act was passed. It was designed to “help Indians live more like Whites” by dividing up reservation lands so they could all own individual farms. However, the farms in northern Wisconsin were not good for farming—so many of the Ojibwe sold their land to supplement their wages.

On some reservations, over 90% of the land passed into White hands.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

When Did Things Start To Change?

Finally, in the 20th century, under the administration of President Franklin D Roosevelt, Ojibwe communities along the St Croix River in northwestern Wisconsin and those at Mole Lake in northeastern Wisconsin (which had not received reservations before) were given reservation lands.

The St Croix Ojibwe received 1,750 acres in 1938, and the Mole Lake band received 1,680 acres in 1937. And while this is great news, the true victory came along a few decades later.

Whitney & Zimmerman, Wikimedia Commons

Whitney & Zimmerman, Wikimedia Commons

Their Right To Provide

Back when the Ojibwe signed the 1837 and 1842 treaties, they reserved the right to hunt and fish on the lands they had ceded to the United States. But for many years, the state of Wisconsin actually convicted Ojibwe people who fished and hunted off their reservations without licenses.

For many years, they were robbed of their rights to provide for themselves—but all that changed in 1983.

The 1983 Victory

The Wisconsin Ojibwe's' greatest victory in reclaiming their treaty-reserved rights came in 1983 when the federal courts affirmed that the two treaties guaranteed Wisconsin Ojibwe's' right to hunt and fish on the land they ceded to the United States.

But as usual, not everyone agreed—and the Ojibwe found themselves targets once again.

Hostile Encounters

When the Ojibwe started fishing freely again, they were met with hostile behaviors by non-Natives. They were often harassed, withstanding physical assaults and racial slurs.

On top of that, the state of Wisconsin tried to fight the court’s decision—even sinking to an unbelievable low.

National Parks Gallery, Picryl

National Parks Gallery, Picryl

Desperate Measures

The state of Wisconsin really didn’t want the Ojibwe people to live off their own lands, and tried desperately to challenge the court’s decision. When the federal court denied their appeals, they went as far as offering millions of dollars to the Ojibwe people to relinquish their treaty rights—but they didn’t give in.

Did They Ever Get Peace?

The Ojibwe never gave in, and they continued to live off the land regardless of the hostility they were met with. Eventually, by the 1990s, the violence had simmered down, and the Ojibwe have gone above and beyond to help stock walleye in the lakes where they often spearfish.

Canadian Treaties

In Canada, the British agreed to many land cession treaties made with the Ojibwe, providing rights for continued hunting, fishing, and gathering of natural resources after land sales. These treaties span Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta.

Treaties in both Canada and the US continue to be discussed and adjusted even today, as many are vague and difficult to apply in modern times.

Final Thoughts

While the Ojibwe people have a long history of land disputes and warfare, their legacy lies in their traditional culture, and how they’ve managed to keep true to their roots regardless of outside challenges.

Today, many Ojibwe people continue to thrive off the land, passing on invaluable hunting, fishing, and foraging skills to the younger generations. Many rituals and ceremonies are still practiced, and clan memberships continue to take a traditional lineage—keeping strength in their community.

Heidi Mühlenberg, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Heidi Mühlenberg, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons