The Most Mysterious Map In History

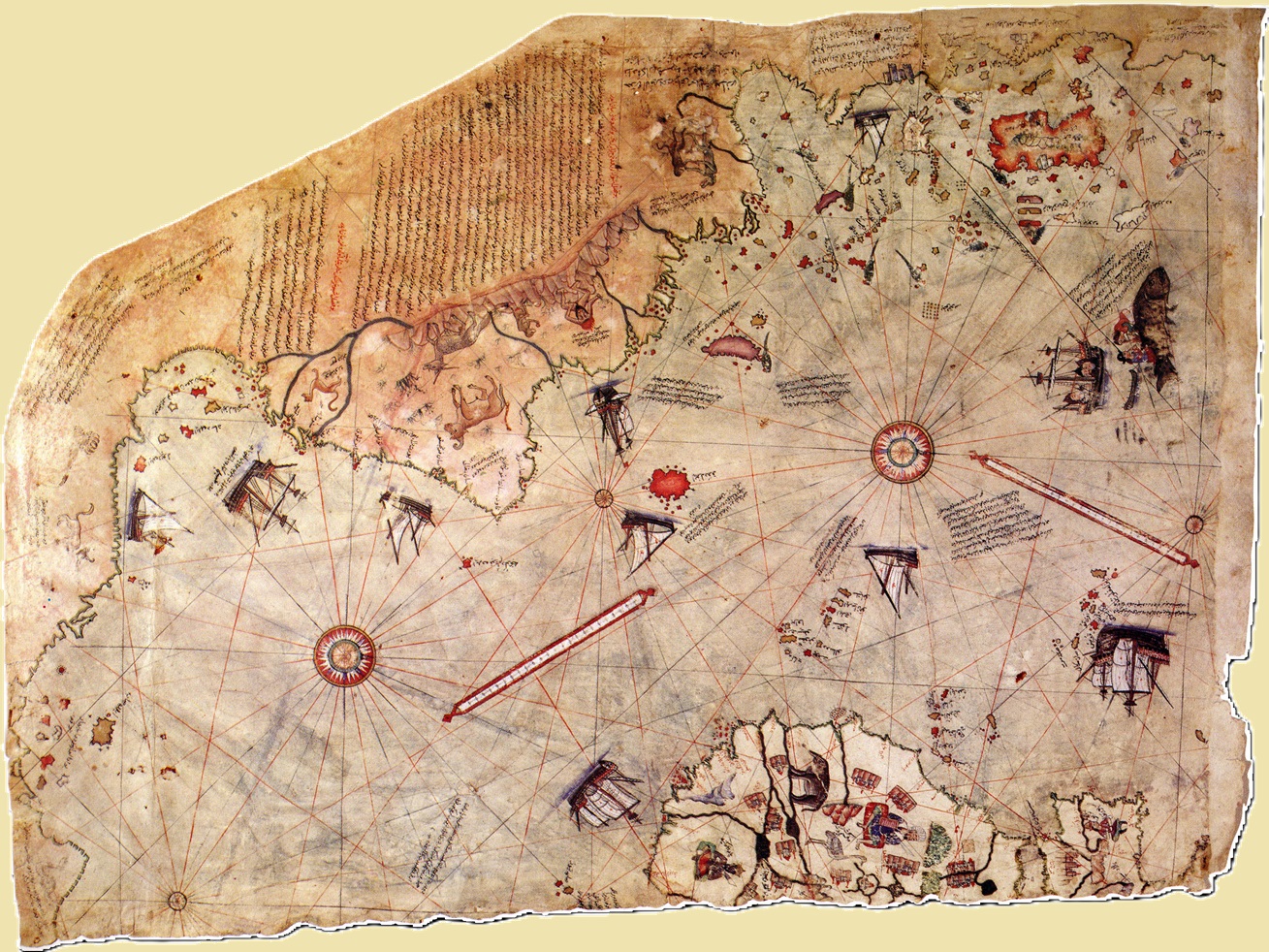

The Piri Reis World Map of 1513 is one of the oldest post-Columbian world maps in existence. It was created during a time when much of the New World was still being discovered by Europe. Yet, somehow, the details are incredibly precise.

Considering it was created long before geolocation technology existed, the map’s accuracy has puzzled historians for centuries, making it one of the world’s most mysterious maps. From theories of lost civilizations to paranormal assistance, let’s uncover the mystery behind the oldest surviving “Map of America".

The Incredible Discovery

Before we delve into the details of who created the map and how, let’s first understand the magnitude of its discovery.

It was found in the Library of Topkapı Palace in Istanbul in 1929, when the palace was being converted to a museum. The map, which is dated 1513, is drawn on parchment made from gazelle skin, and only a portion of the original is known to have survived over the years.

What Does The Map Look Like?

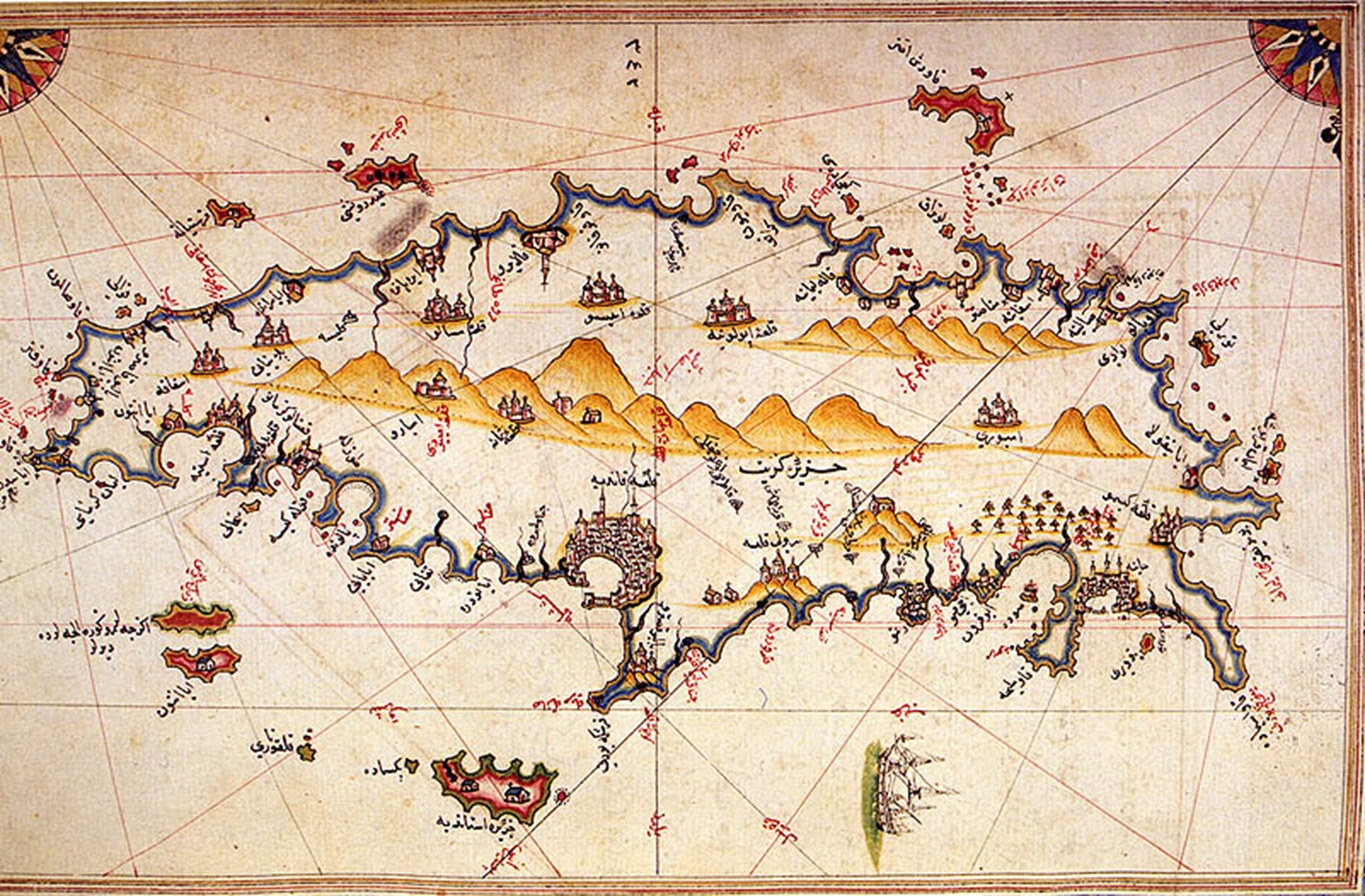

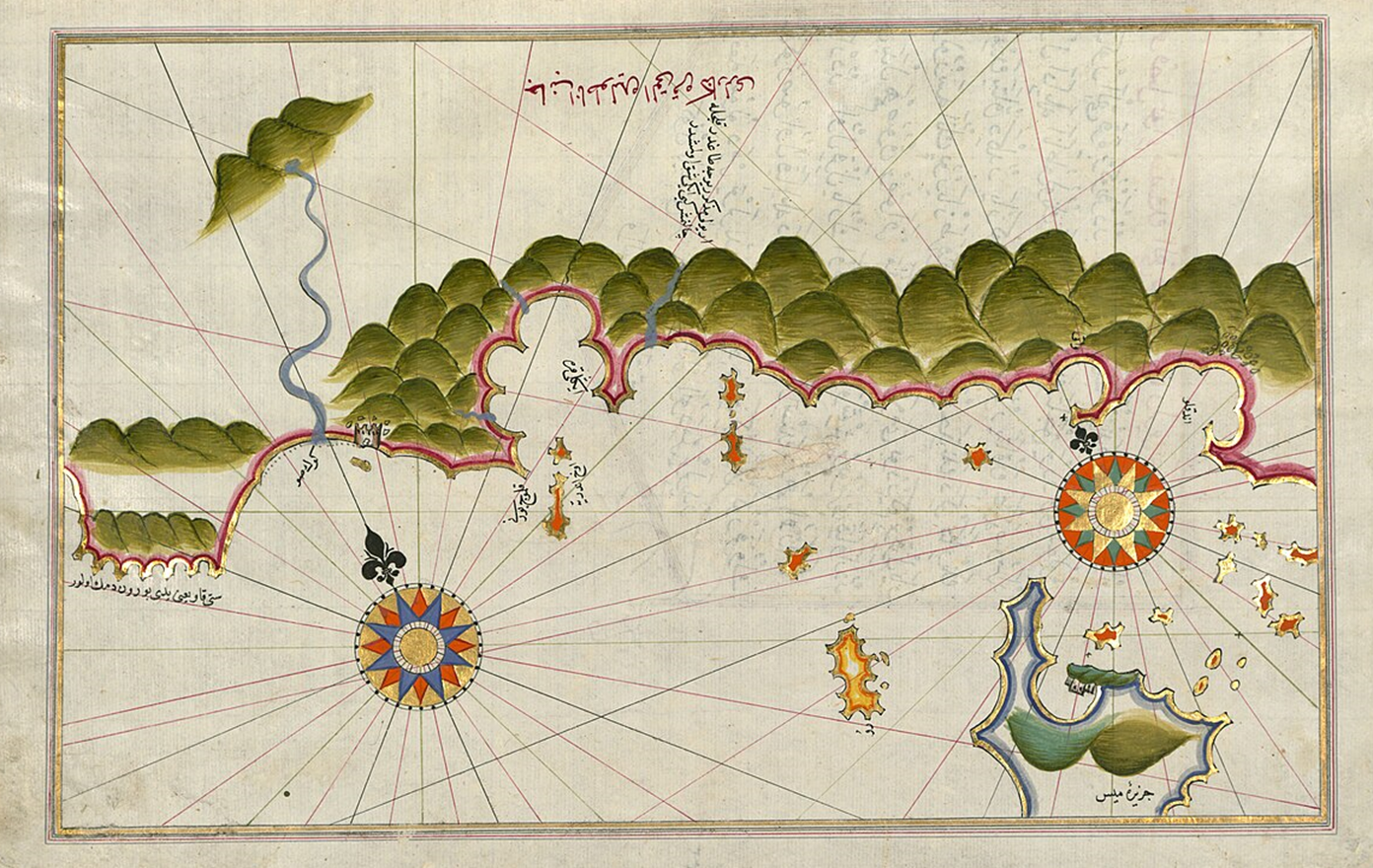

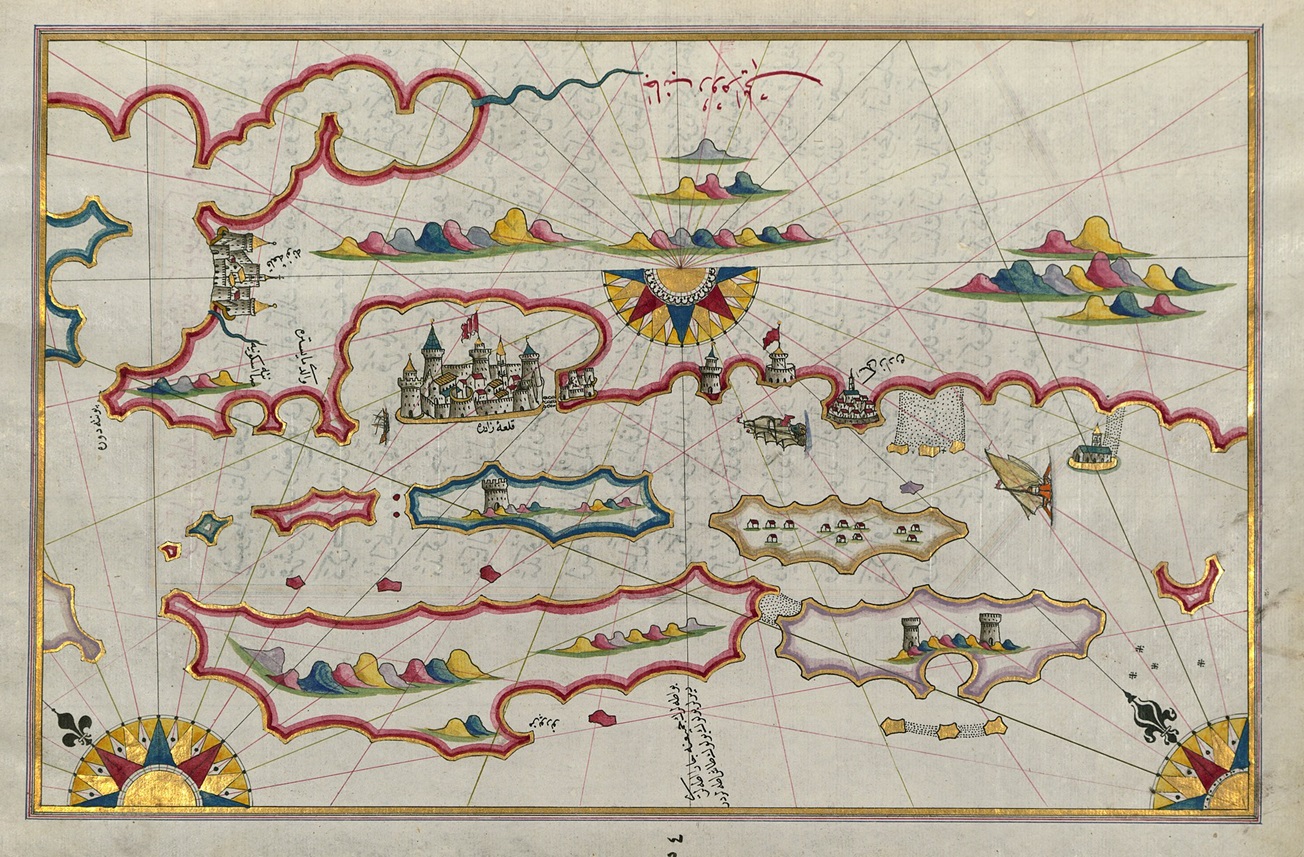

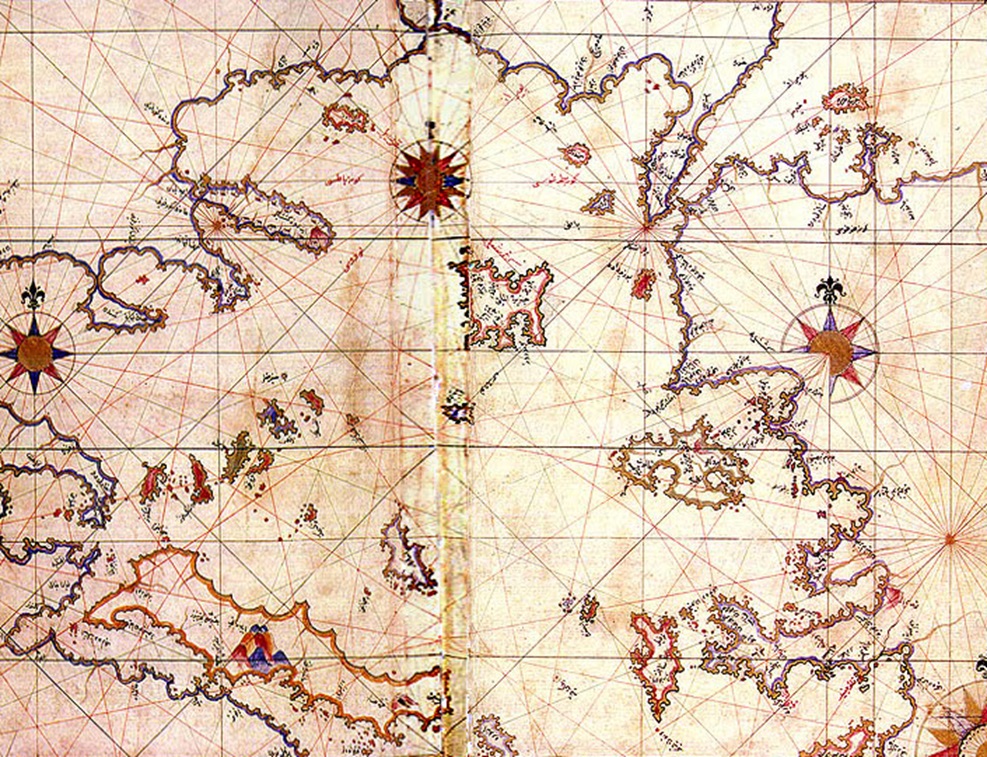

The remaining piece of the map is approximately 87 cm x 63 cm. It is a portolan chart with compass roses from which lines of bearing radiate. This particular piece of the map focuses on the Atlantic and the Americas, showing the Atlantic Ocean with the coasts of Europe, Africa, and South America.

Map Specifics

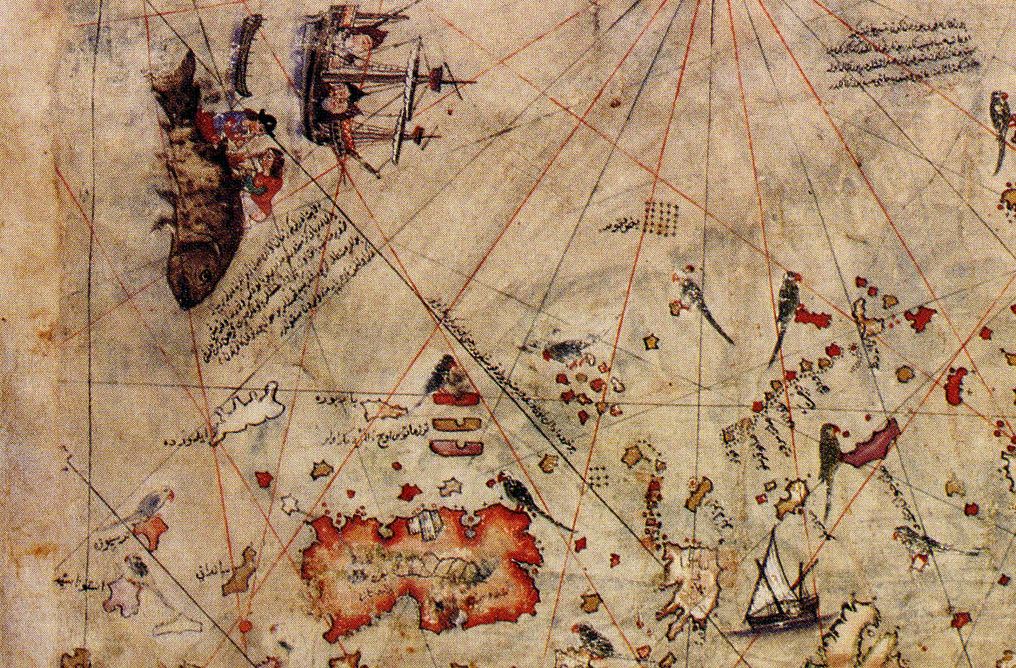

In the top left corner, the Caribbean is arranged unlike modern or contemporary maps. The large island oriented vertically is labeled Hispaniola, and the western coast includes elements of Cuba and Central America.

The distance between Brazil and Africa is roughly correct, and the Atlantic islands are drawn consistent with European portolan charts.

But not everything is explainable.

Rjjiii, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Rjjiii, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Phantom Islands

Many places on the map have been identified as phantom islands or have not been identified conclusively. For example, İle Verde (Green Island) north of Hispaniola could refer to many islands. And the large island in the Atlantic, İzle de Vaka (Ox Island), corresponds to no known real or fictional island.

Both an Atlantic island and the mainland of the Americas are referred to as the legendary Antilia.

Within the map are extensive notes, written with the Arabic alphabet. Inscriptions on South America and the Southern Continent cite recent Portuguese voyages, and are written in Ottoman Turkish.

Rjjiii, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Rjjiii, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

A World Not Yet Discovered

At the time of its creation, the well-known Old World had been explored and mapped for centuries, so the mapping of it was quite accurate at the time. But the New World, however, was mostly unexplored, and drawing a map based on the few documented and recorded voyages to it required thorough research of all known sources.

Jacob d'Angelo, Wikimedia Commons

Jacob d'Angelo, Wikimedia Commons

A Cartographer Ahead Of His Time

The map’s seemingly accurate details of the recently discovered North and South American continents, as well as the plotted lines, give the impression that the chart was made by a cartographer who was ahead of his time.

Karamanli86, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Karamanli86, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

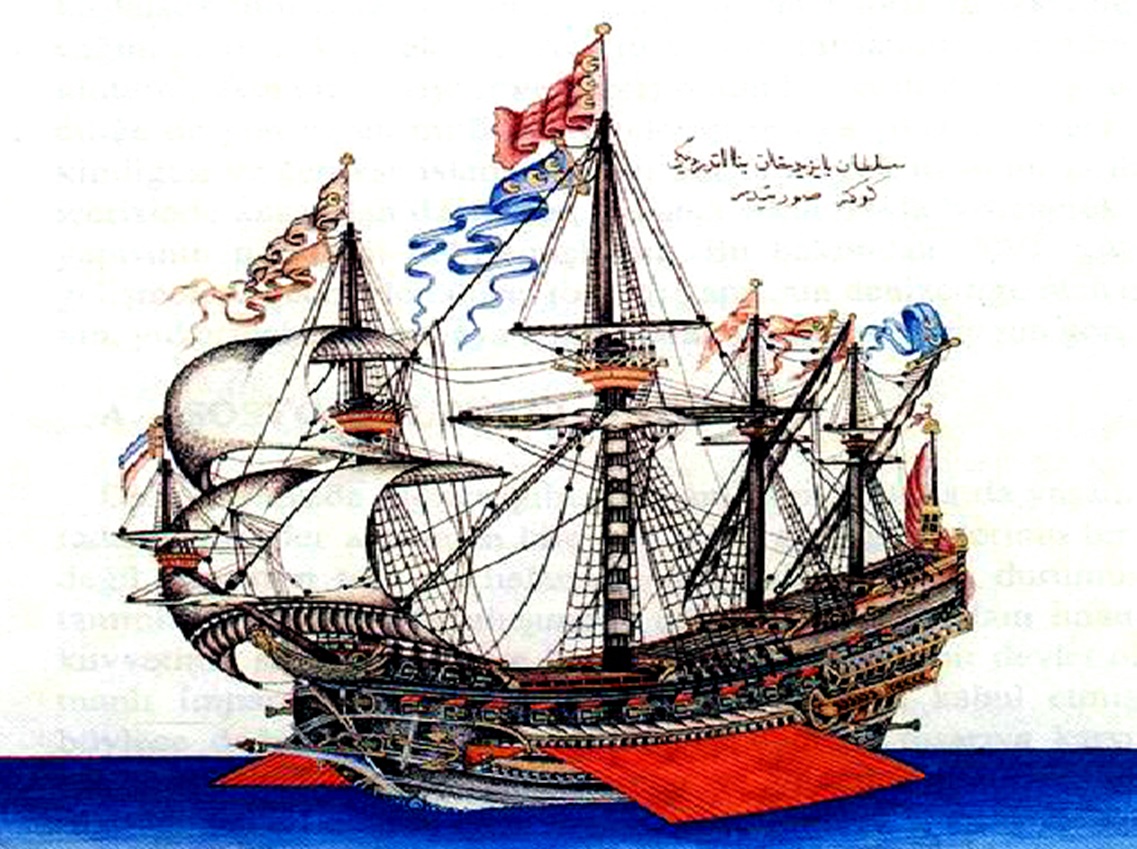

Masters Of The Sea

The 1929 discovery was monumental, causing a thrilling stir among scholars, and an even bigger excitement in Turkey as the map was now proof that the Turks had once been masters of the sea.

So, who created this map and how did they do it?

Piri Reis

The creator of the map was Ahmed Muhiddin Piri (1465-1553), better known as Piri Reis. He was an Ottoman navigator, geographer and cartographer. He gained fame long after his demise, when this map was discovered. But his life was anything but ordinary.

CeeGee, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

CeeGee, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

He Came From A Line Of Heroes

Piri was born in Gallipoli, a major naval base belonging to the Ottoman Empire in Turkey. Not much is known about his childhood or his parents, but we do know that he started sailing from an early age with his uncle, Kemal Reis—one of the outstanding Turkish naval heroes of the period.

Together, they fought as corsairs—also called privateers—before they eventually joined the Ottoman Navy.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

He Had An Interest In Cartography

Piri’s life at sea stirred something up inside him. A thirst for knowledge and exploration. A desire to find out more.

In 1511, after fighting many battles in the Ottoman-Venetian wars, his uncle passed. It was then that Piri decided to return home and begin his cartographic works—starting with his first world map.

British Museum, Wikimedia Commons

British Museum, Wikimedia Commons

He Went Back To The Navy

A few short years later, Piri went back to the navy and took part in the Ottoman conquest of Egypt. He was dedicated to his leader, so after their victory, he presented his world map to Sultan Selim I—giving the Turks an accurate description of the Americas and the circumnavigation of Africa well before many European rulers.

Aşık Çelebi, Wikimedia Commons

Aşık Çelebi, Wikimedia Commons

He Kept Researching

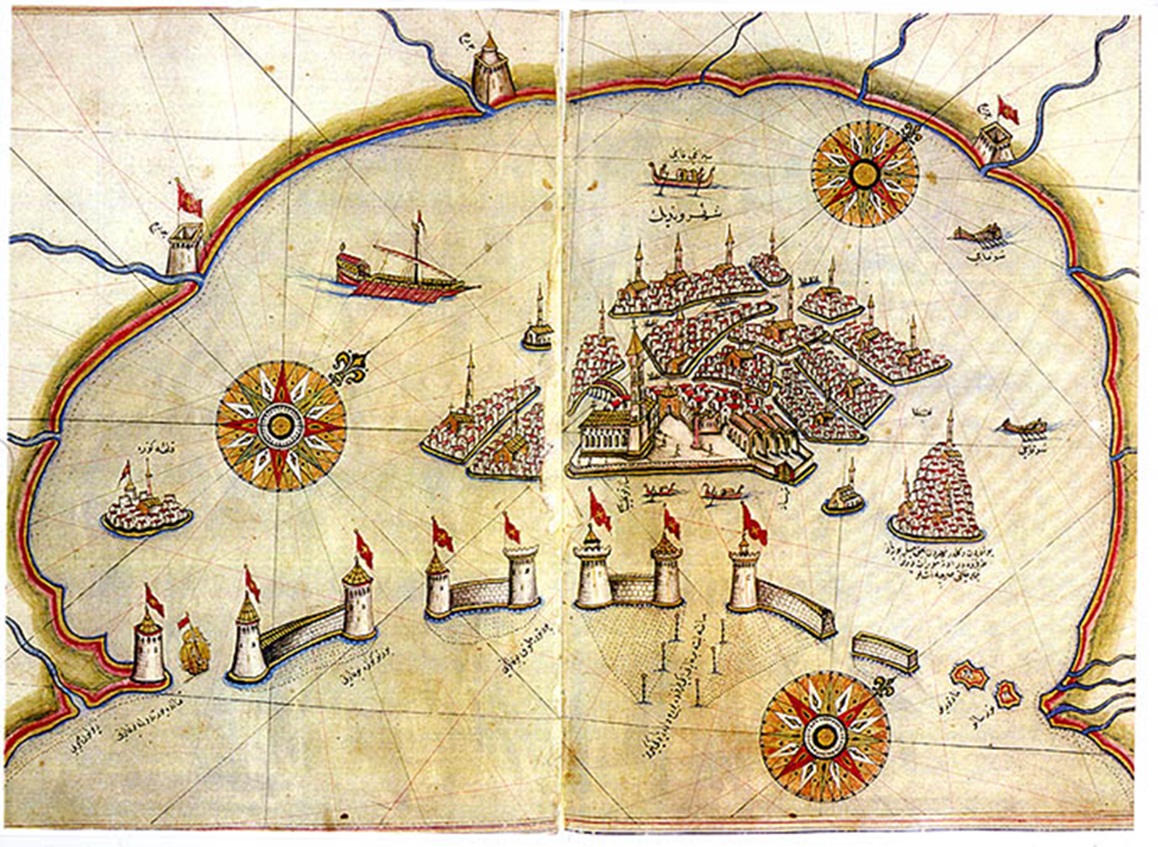

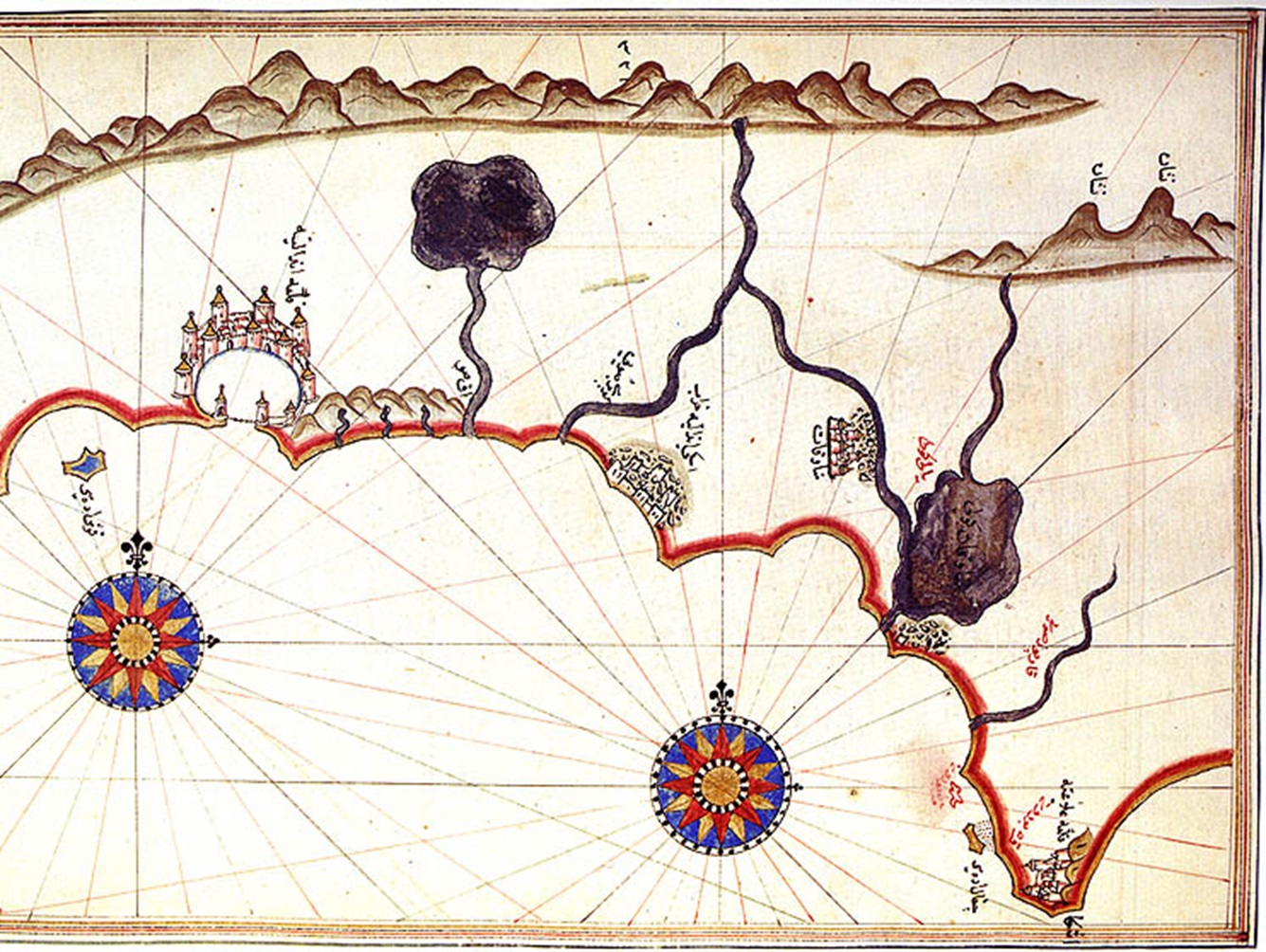

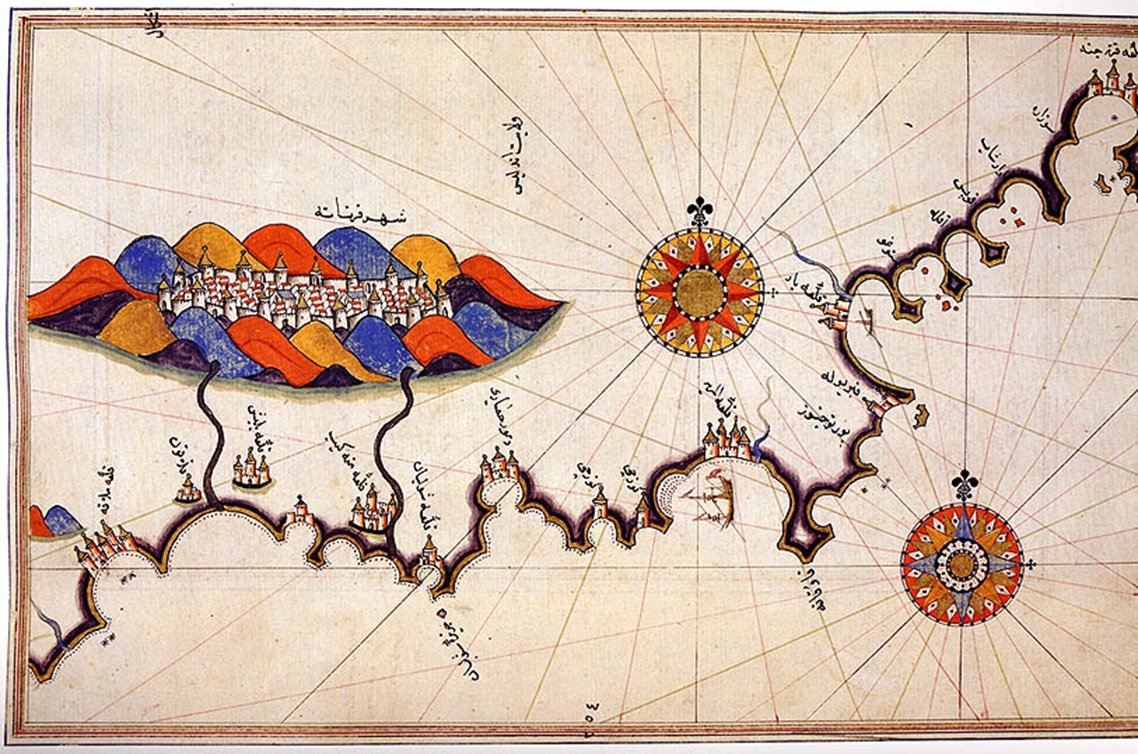

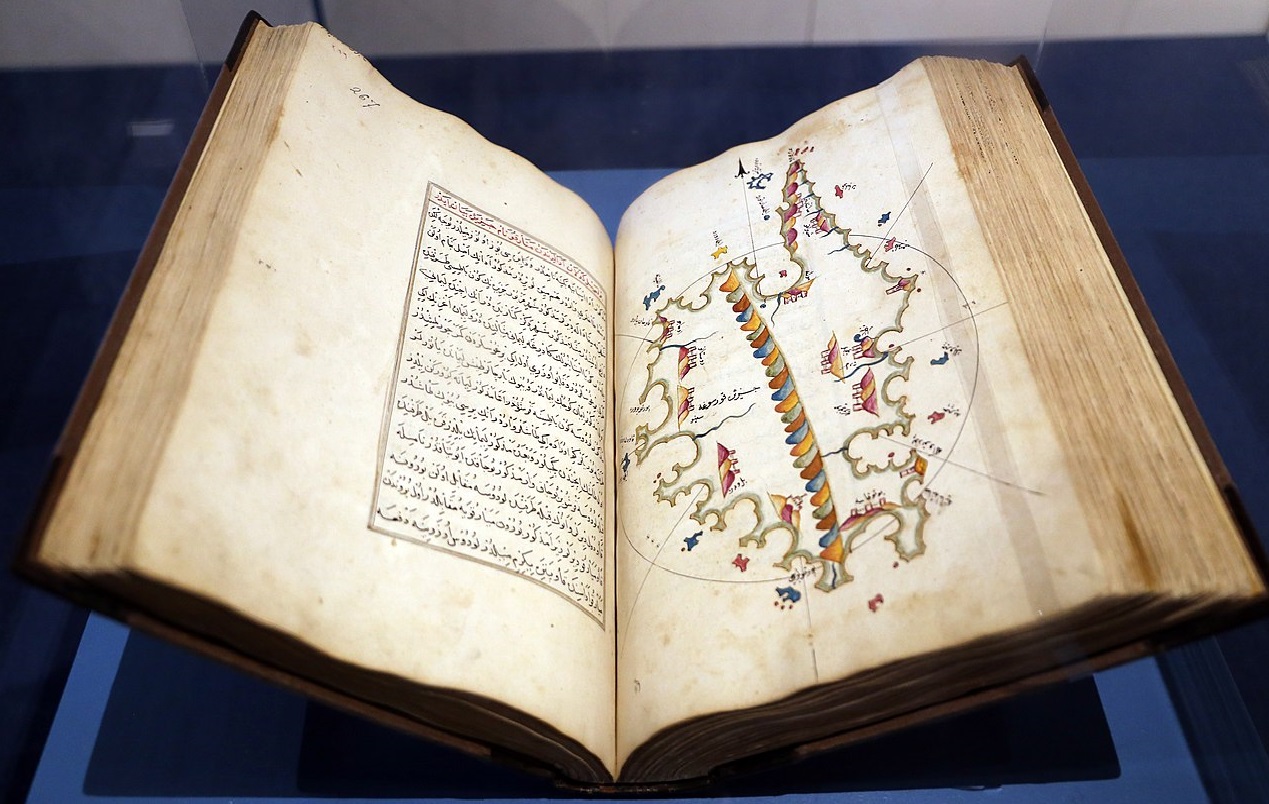

Feeling encouraged, Piri continued his work, creating an entire book of detailed information on early navigational techniques as well as relatively accurate charts for their time, describing the ports and cities of the Mediterranean Sea.

Later, this book would become one of the most famous cartographical works of the period.

He Became Admiral

In 1516, Piri was again at sea as a ship captain in the Ottoman fleet, fighting numerous—and victorious—battles. By 1547, he had risen to the rank of Reis (admiral) as the Commander of the Ottoman Fleet. He fought for many years, returning to Egypt as an old man approaching 90.

He Was Beheaded

In 1553, Piri refused to support the Ottoman Vali (Governor) of Basra, Kubad Pasha, in another campaign against the Portuguese and paid for it with his head—literally.

But even after his brutal demise, Piri Reis’ name lived on. Not only were several warships and submarines named after him, but centuries later, his world map would become an international treasure—permanently marking his name in history books.

Mkadioglu2020, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mkadioglu2020, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

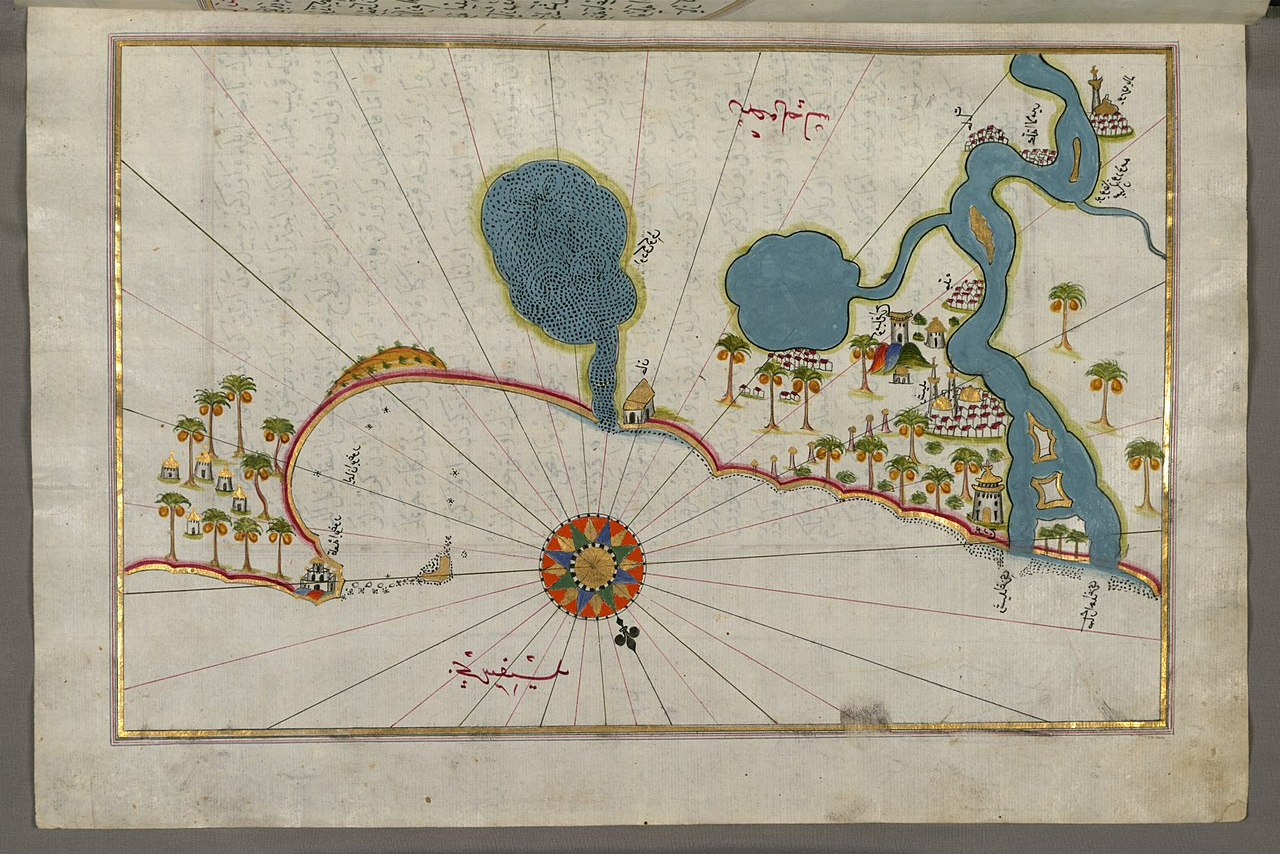

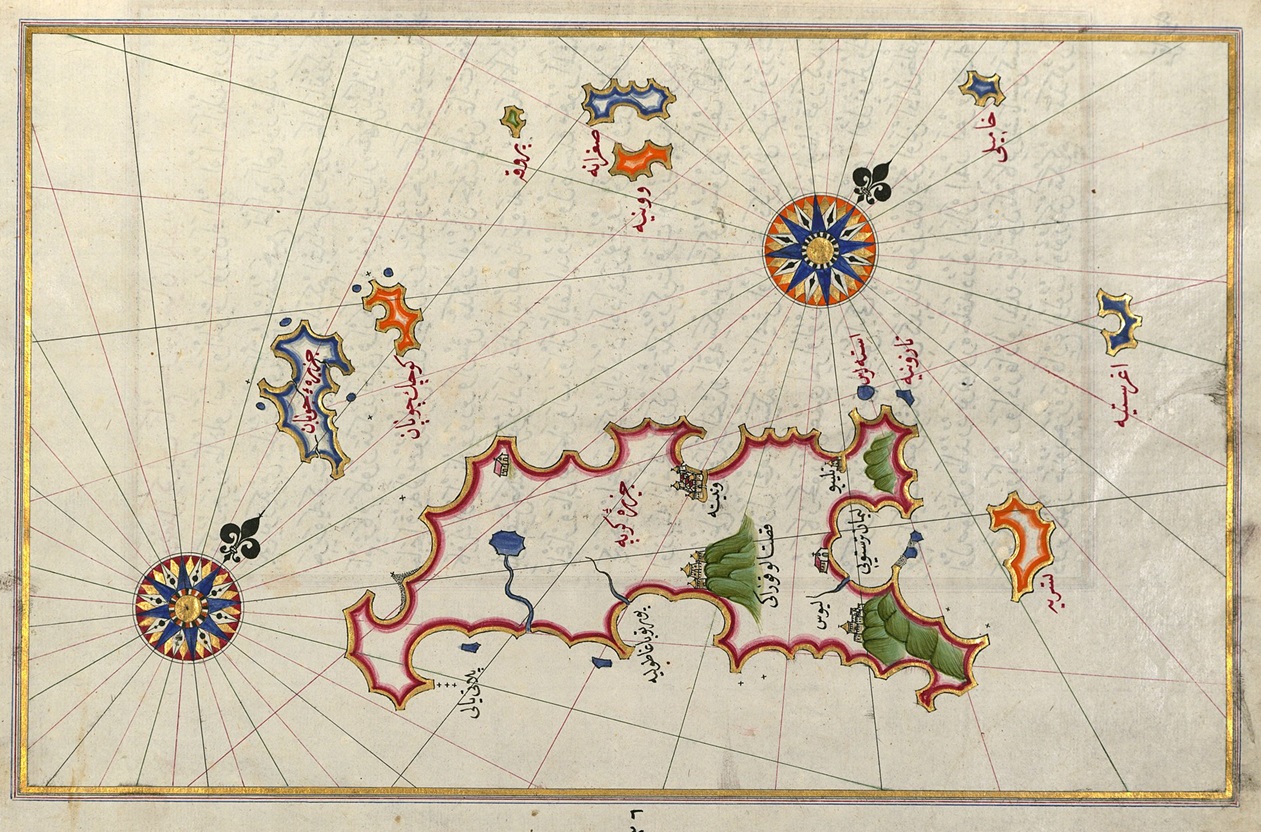

The Kitab-ı Bahriye

Piri’s book—first published in 1521—is titled, Kitab-ı Bahriye (Book of Navigation), and it combines information about the New World from a range of sources as well as his own personal experiences.

Sailko, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sailko, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Kitab-ı Bahriye

The book gives navigators information on the Mediterranean coast, islands, crossings, straits, and gulfs, as well as where to take refuge in the event of a storm, how to approach the ports, and precise routes to the ports.

All of which gave the Turks quite an advantage.

He Was Detail Oriented

Piri compiled charts and notes from his career at sea into the most detailed portolan atlas in existence. But how he compiled this book is what historians find most fascinating.

He Was Resourceful

Piri Reis was not exactly a world explorer and had never actually sailed to the Atlantic. So, while he may have used some of his own experiences, the majority of his world map was assembled by referring to 20 other regional maps, including an Arab map of India, four Portuguese maps showing India and China, and a map “of the Western Parts,” the coasts, and islands.

He Had Access To A Missing Map

Piri’s first world map is a portolan (nautical) chart with compass roses and a Windrose network for navigation, rather than lines of longitude and latitude. It contains extensive notes written primarily in Ottoman Turkish.

But some of its features bore resemblance to another historical map, one that had been missing for decades at this point—or so we thought.

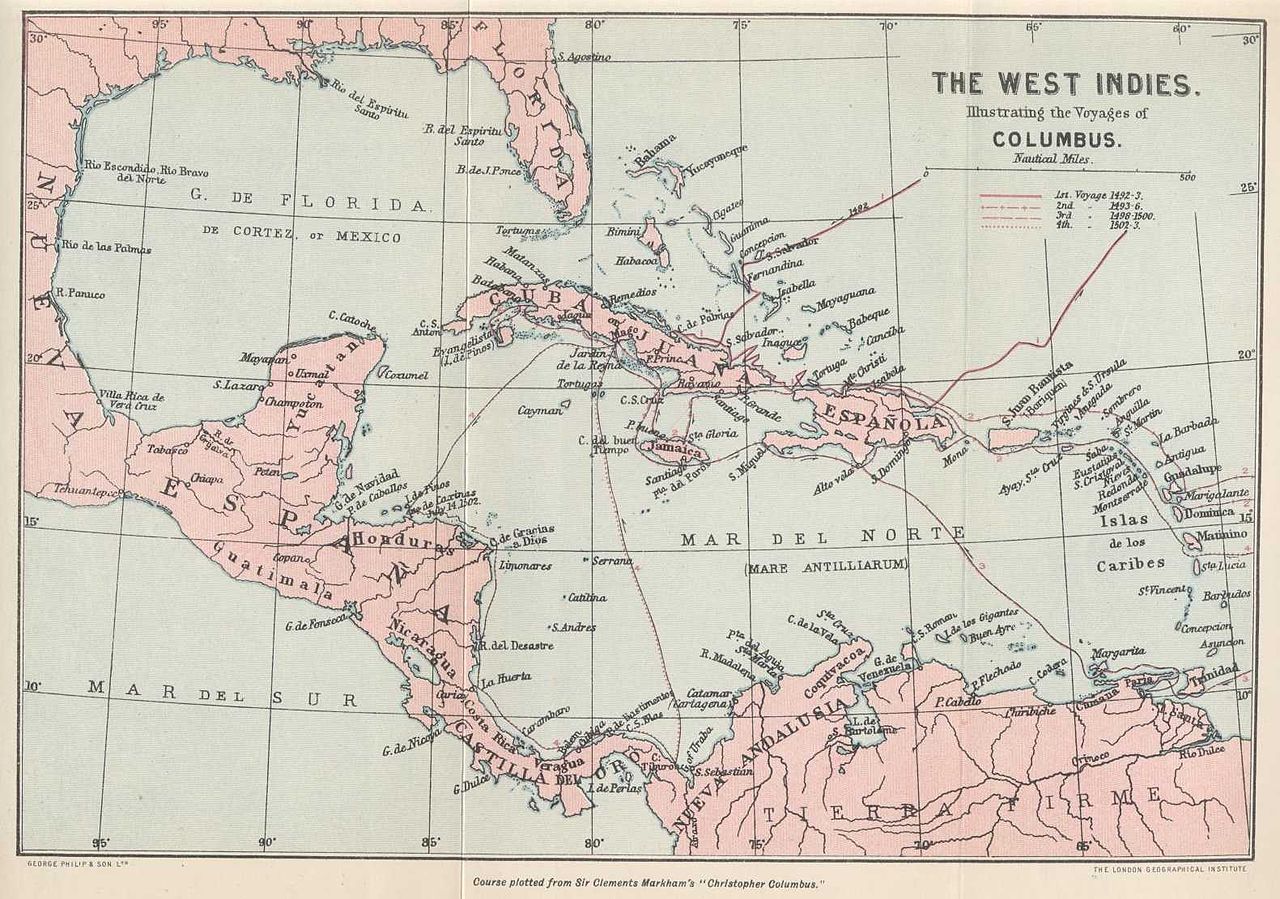

He Sourced From Christopher Columbus

On Piri’s world map, the northwestern coast combines features of Central America and Cuba into a single body of land. Scholars believe the peculiar arrangement of the Caribbean was taken from the now-lost map created by Christopher Columbus that merged Cuba into the Asian mainland and Hispaniola with Marco Polo's description of Japan.

This reflects Columbus's inaccurate claim that he had found a route to Asia—but proves that Piri had access to the missing map.

Historical Society of Old Yarmouth, Picryl

Historical Society of Old Yarmouth, Picryl

He Credited Columbus

Piri gave credit where it was due, though. On his map, he imprinted the description “these lands and islands are drawn from the map of Columbus"—which is what excites historians the most.

He Provided Missing Pieces To The Puzzle

Columbus made the last map Piri mentions during his third voyage to the New World. Columbus then sent it to Spain in 1498—but then it was never seen again. It has been considered “lost” for years. So now, with Piri’s map, historians can see what Columbus must have recorded.

Keith Pickering, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Keith Pickering, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

His Map Instantly Made History

Piri’s map was an incredible find. There is nothing historians hate more than lost historical documents—especially those involved in world geography. Christopher Columbus’s map was made 21 years before Piri’s map, and shortly after he reached the New World. Its loss was devastating back then, and still is today.

So, the fact that Piri’s map was created with the help of Columbus’s lost map is big news for the history books.

Islamic Influence

Piri’s world map is visually different from European portolan charts as it was influenced by the Islamic miniature tradition (small paintings). But it was also unusual in the Islamic cartographic tradition for incorporating many non-Muslim sources.

That’s not the only thing that’s different, though.

Scholarly Analysis

According to scholars, compared to the Islamic cartography of the era, Piri’s map shows “an atypical knowledge of foreign discoveries". During the Age of Discovery, European voyages expanded the known world and refuted the traditional idea of an "inhabited quarter" of the world.

And the attitudes towards the Age of Discovery within the Ottoman Empire ranged from passive indifference to the outright rejection of foreign influence.

Scholarly Analysis

Piri blends traditional views with new discoveries by suggesting that European findings are not new, but rather a rediscovery of ancient knowledge. He often refers to Dhu al-Qarnayn—believed to be a reference to Alexander the Great from the Quran—in his inscriptions regarding Columbus.

Crediting Alexander

According to the Quran and Turkish literary tradition, Alexander traveled to every corner of the world, thereby defining its limits. A minor inscription by Piri describes world maps as "charts drawn in the days of Alexander". Another inscription mentions that a "book fell into the hands" of Columbus describing lands "at the end of the Western Sea".

In Piri’s 1526 version of his book, he explicitly credits European discoveries to lost works created during the legendary voyages of Alexander.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Questioning Its Accuracy

Piri’s map wasn’t the only one at this time. Compared to earlier portolan maps, his shows gradual improvement: the Atlantic Ocean is accurate, South America is highly detailed, and the Caribbean is strangely organized.

Piri’s Updated Version

In 1528, Piri Reis updated his map to include a more detailed and accurate version of the New World—and despite its strange level of accuracy, scholars had lots to say about it.

Gregory McIntosh

Independent scholar and well-known author in early modern exploration and cartography, Gregory McIntosh (who actually studied the Piri Reis Map extensively) found that: “The Piri Reis map is not the most accurate map of the sixteenth century, as has been claimed, there being many, many world maps produced in the remaining eighty-seven years of that century that far surpass it in accuracy".

Bad Omens

Piri’s sources were not the only cause for concern though. Along his map’s Western edge, he drew a variety of strange monsters from medieval mappaemundi (world maps) and bestiaries—which are open to various interpretations.

American Monsters

Among the mountains in South America, a headless man is depicted interacting with a monkey. The headless men, known as Blemmyes, were portrayed in medieval maps and books as threatening. In Islamic culture, monkeys were considered ill omens.

Some scholars believe the map’s monsters “reinforce the notion that the Encircling Ocean is full of scary beasts and therefore should not be crossed".

The Southern Continent

Aside from a debate about the sources Piri used, many areas on the map have not been conclusively identified with real or mythical places. Some authors have claimed that it depicts areas of South America that were not officially discovered yet in 1513—including an intriguing theory about Antarctica.

Discovering Antarctica

One of the hottest debates about Piri Reis’s map is the depiction of an ice-free continent (now known as Antarctica) in the South Atlantic—which most historians agree wasn’t spotted by Europeans until 1820.

Because of this, some believe the map is too advanced for its time.

An Ice-Free Antarctica

The fact that Antarctica was depicted as being free of ice is the biggest red flag. Geologists agree that the last time this continent was ice-free was more than 34 million years ago. Before that, the continent was free of ice for nearly 100 million years.

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Balancing The Map

Some theorists believe that it was probably assumed that a huge land mass existed on each of the four sections of the Earth in order to “balance it out".

But that’s not the only problem scholars have with the map.

Too Many Details

The map is incredibly detailed, showing mountain ranges, rivers, dry plains, and interior land features. It also has drawings of kings, Indigenous clothing of various regions, elephants, birds, oxen, parrots, llamas and snakes. Several ships are drawn sailing the seas with explanatory inscriptions beside them.

These remarkable details are one of the very reasons many people believe the map to be fake. This is when conspiracy theories began circulating—including one other-worldly possibility.

Help From Another World

In the 1960s, people started to think the map may be the work of the paranormal. If you’re familiar with paranormal theories, it is often believed that other lifeforms exist in the universe and that they are much more advanced than humans.

And people have reasons to back this up.

Azimuthal Projection

The Piri Reis map does not have the typical latitude and longitude lines that modern maps and charts use. Instead, it contains lines called azimuth that originate from a center known as a compass rose, or azimuthal projection.

Erich von Däniken, paranormal investigator and ancient astronaut enthusiast, explains this further.

Erich Von Däniken

Without testing his hypothesis, Däniken wrote that the projections shown on the Piri Reis map fit well when the center was Cairo, Egypt. Based on this, he believed that the map was very accurate in terms of scale, and that it was not humanly possible in the 16th century for anyone to have created such a map.

Alien Intervention

Instead, he believes the map is proof that the Ottomans were in contact with “aliens,” or some other advanced lifeform, who helped them create new technology and knowledge.

If that’s too far-fetched, there’s another theory.

Taking It Back To The Ice Age

Von Däniken wasn’t the only one with a questionable theory. In 1966, amateur historian Charles Hapgood claimed the map proved there was an unknown advanced civilization from the ice age that had explored the world, and that this map was a copy of one of theirs.

His proof? The map showed a dry Antarctica. That’s it. That’s his only evidence. But it doesn’t stop there.

Pyramids In Antarctica

Several years ago, though, an article went viral claiming that pyramids were discovered in Antarctica. Though the information was vague, it did include a handful of questionable images that supposedly showed the pyramids.

This caused many people to revisit the theory that a lost civilization had once roamed the frozen continent, and that the Piri Reis map may accurately depict Antarctica after all.

Final Thoughts

The Piri Reis Map of the World is one of the oldest maps of America still existing anywhere today. The map has captivated and mystified scholars for years with its seemingly accurate details, giving rise to myths and legends of all kinds.

The story of the Piri Reis map is one that mixes reality and fantasy, and is a rabbit hole worth exploring for those who love a good historical mystery.