Researchers Have Discovered America's Last Known Slave Ship

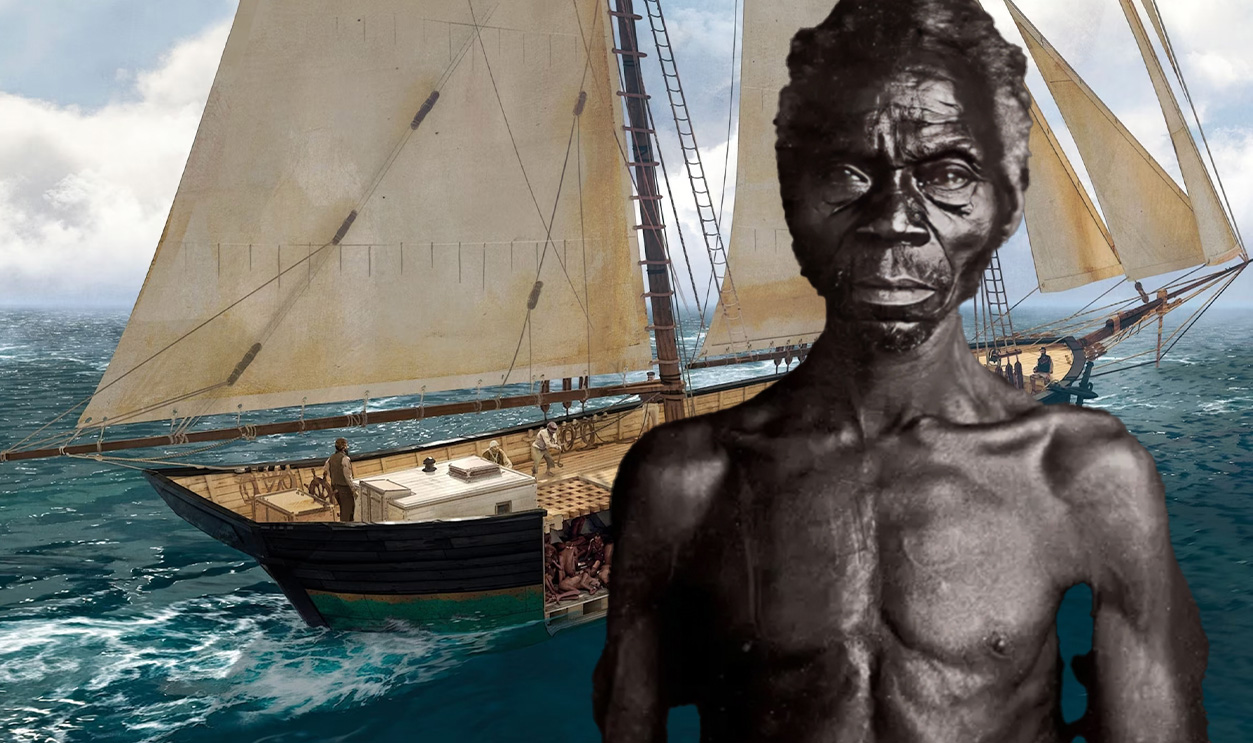

In 2019, archaeologists discovered the remains of Clotilda, the last known slave ship to sail to the United States from Benin, West Africa. This is the story of Charlie Lewis, an enslaved person who was ripped from his homeland in West Africa and brought to Alabama aboard the last known slave ship to come to America.

The Clotilda Slave Ship

The Clotilda is the last known slave ship to leave Africa, transporting enslaved people to the United States. It was discovered in 2019 in the Mobile River, Alabama. But Clotilda's dark history begins centuries earlier. Let's explore the history of the American slave trade before we tell the story of Charlie Lewis, the great-great-grandfather of Alabaman Lorna Gail Woods.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The History Of The American Slave Trade

While the concept of slavery was not an American invention, the slave trade in the United States is one of the most well-known in history. Still, establishing a slave trade route began in the 16th century, as European sailors contacted isolated tribes in Africa via sea exploration.

Frederick James Smyth, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Frederick James Smyth, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Doctrine Of Discovery

One of the main precursors to the establishment of the slave trade was the Doctrine of Discovery, enacted by Pope Alexander VI in 1493, which was a directive from the Church that the Spanish should take (and rule) lands from non-Christians and that Indigenous people should be converted to Christianity.

Attributed to Pedro Berruguete, Wikimedia Commons

Attributed to Pedro Berruguete, Wikimedia Commons

Claim And Colonize All Non-Christian Lands In The Americas

The Pope's papal bull gave Spanish and Portuguese sailors the authority to claim and colonize all non-Christian lands in the Americas. Despite slavery existing in both Spain and Portugal for centuries, social status and religious identity were the primary factors for enslavement—not one's racial identity. This practice changed in the 16th century, with disastrous consequences.

Livro das Armadas, Wikimedia Commons

Livro das Armadas, Wikimedia Commons

Two Portuguese Men Begin The African Slave Trade

In 1441, before the edict from the Pope, two Portuguese men began the African slave trade. Nuno Tristâo and Antônio Gonçalves sailed to Mauritania in West Africa, kidnapped 12 people, and returned to Portugal to present them to Prince Henry The Navigator. This began a practice that saw between 700 and 800 slaves taken from West Africa and imported to Portugal by 1460.

Nuno Gonçalves, Wikimedia Commons

Nuno Gonçalves, Wikimedia Commons

The Slave Trade Continues

Throughout the centuries that followed, the slave trade between Portugal and Africa intensified, with the Portuguese establishing a near-monopoly over slave trading in West Africa, codified in the Treaty of Tordesillas, establishing Portuguese and Spanish ownership over lands in West Africa.

Henry Samuel Hawker, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Samuel Hawker, Wikimedia Commons

Britain Becomes A Major Player

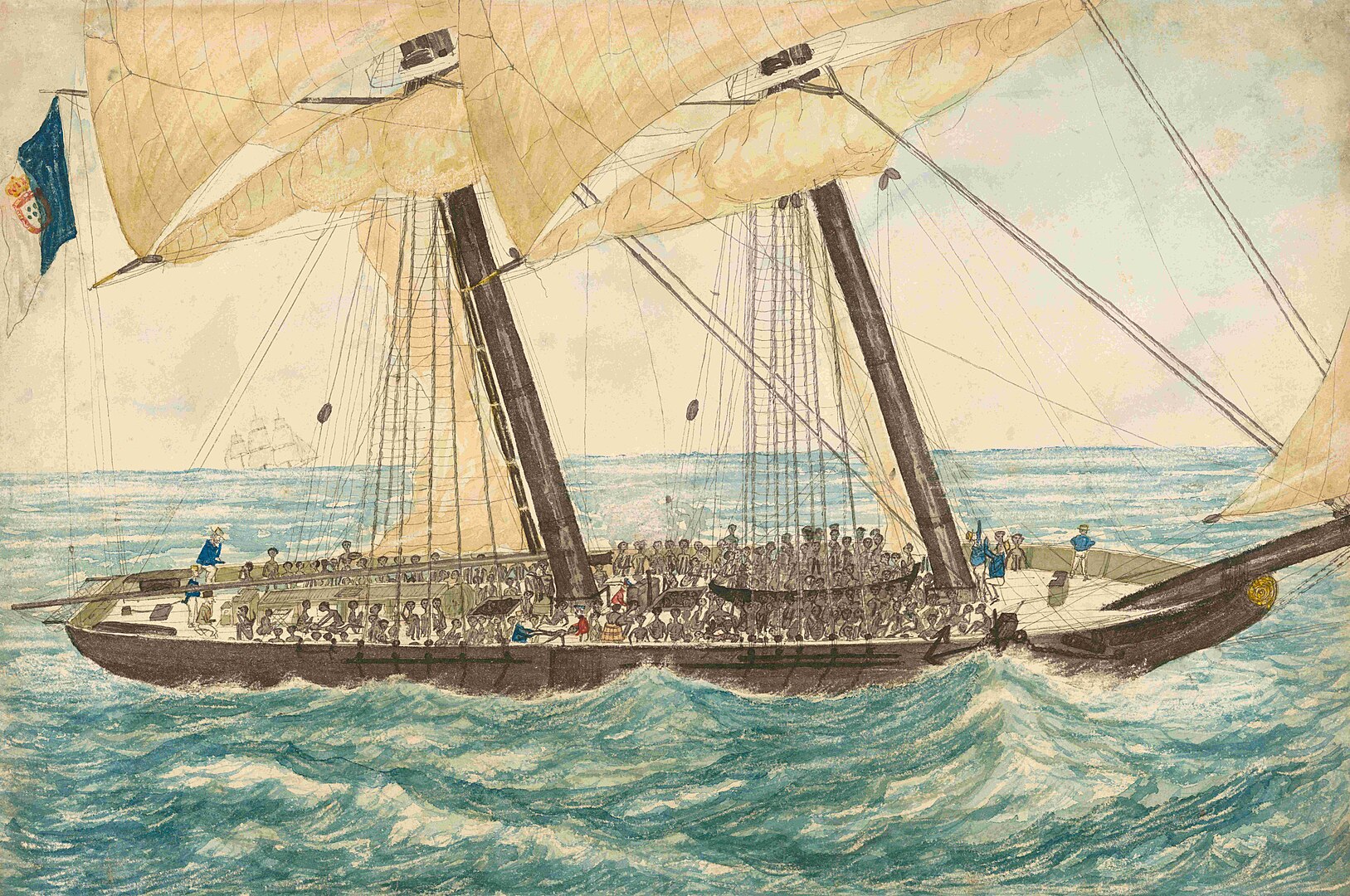

Although not originally a major player in the slave trade, Britain began participating in the transatlantic slave trade in 1562. At the same time, the British were developing a presence in North America, a part of the world that was rich with untapped resources. The British used a navigational triangle—from Europe to Africa, then to the Americas, then back to Europe—to transport as many as 3 million people into slavery in the Americas.

Nicholas Matthews Condy, Wikimedia Commons

Nicholas Matthews Condy, Wikimedia Commons

Establishing A Slave Trade In The United States

While originally known as the "New World," the British were among the chief exporters of slaves to the United States. By conservative estimates, as many as 264,000 British ships transported slaves from Africa to North America, particularly to the southern United States. This established trade continued between 1562 and 1865, when the United States abolished slavery.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Illegal Slave Importation Continues

Despite the illegality of slavery, many southern US states that had relied on slave labor continued to import enslaved people from West Africa illegally. Charlie Lewis arrived on one of these slave ships.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Finding The Clotilda—Or Did They?

In 2017, Ben Raines, a journalist with AL.com believed he had located the wreck of the Clotilda, so he established a huge set of research teams to aid him in his quest to uncover the shipwreck.

The Legacy of the Clotilda: The Last Slave Ship, History in Five

The Legacy of the Clotilda: The Last Slave Ship, History in Five

A Multi-Team Effort

The discovery of the Clotilda was a multi-team effort, put together as part of an initiative by the Slave Wrecks Project, an organization dedicated to investigating and uncovering the history of the transatlantic slave trade. In conjunction with the US National Park Service, the Submerged Resources Center, the Alabama Historical Commission, and several research teams from George Washington University and various Museums, they worked hard to uncover the wreck.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

A Multi-Tech Approach

Different types of technologies were required to unearth the incredible wreck of the Clotilda, including dive teams, geographic information systems (GIS), photographic documentation, archival research, and historians from the Smithsonian.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

A Disappointing Discovery

Unfortunately for Raines and his teams, a disappointing discovery was made: the ship they'd uncovered in Alabama was not the Clotilda. It was too long. The Clotilda is known to be just 86 feet in length, while this huge ship was 158 feet long.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

A Different Type Of Wood

Wood used to build the ship was also analyzed using high-tech methods and found to be a soft wood such as pine. It's known that the Clotilda was constructed using oak and yellow pine. That was the definitive sign that Ben Raines and company had got it wrong—the Clotilda remained elusive.

NOAA's National Ocean Service, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

NOAA's National Ocean Service, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Renewed Vigor

Despite the unfortunate setback of not discovering the ship in 2017, Ben Raines' failure did give renewed vigor to the hunt for one of the most important ships in the history of the transatlantic slave trade. Smithsonian curator and SWP director Paul Gardullo stated, "This was a search not only for a ship. This was a search to find our history and this was a search for identity, and this was a search for justice".

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

A Restoration Of Truth

One of the main goals of finding the Clotilda, according to Gardullo, was the restoration of truth and the sense of closure it could bring to the residents of Africatown, Alabama, many of whom are the direct descendants of slaves who were brought to the United States from West Africa centuries ago.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

How Did The Clotilda Make It Back To The United States?

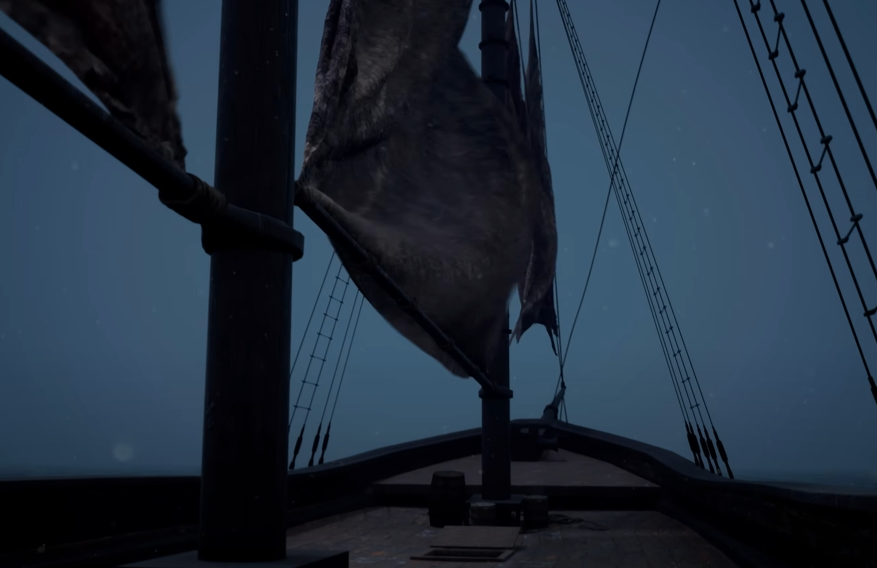

Because slave trading was illegal when the Clotilda was utilized to transport African slaves back to the United States from West Africa in 1860, Alabama plantation owner Timothy Meaher took his schooner from Mobile, Alabama and sailed to the Kingdom of Dahomey, a West African kingdom in a country now called Benin. He sailed back across the Atlantic and snuck into Mobile Bay under the cover of darkness.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Destruction Of The Evidence

After creeping up the Mobile River undetected, Timothy Meaher divided the enslaved persons between him and his ship's captain, William Foster, before selling the rest. He then asked Foster to take the Clotilda upstream and burn it, erasing any traces of the illegal enslavement of people.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

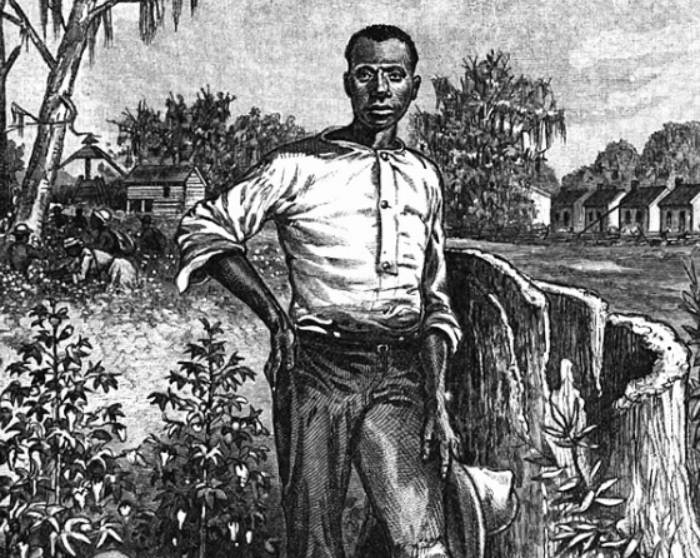

The Clotilda's Survivors Are Freed

After five years of chattel slavery, the Clotilda's survivors were freed from their indentured servitude by the Union Army after the American Civil War. After pooling their wages from selling vegetables and working in fields and mills, they purchased land from the Meaher family and formed a new community.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Africatown Is Born

The land purchased by the survivors of the Clotilda was called "Africatown". It had a strong resemblance to the structures of their beloved homeland, with a chief, a legal system, a church, and a school. Although, of course, all of these institutions have now been modernized, Lorna Woods is among the descendants of the Clotilda who still live there.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

A Pervasive Practice, Even Post-Civil War

The American Civil War has long been thought of as the turning point for slavery in the United States. After all, one of the main consequences was that the practice was officially abolished. Although, as the tale of the Clotilda reveals, it was pervasive regardless of the law.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

The Slave Trade Went A Lot Later Than Most People Think

Lonnie Bunch is the founding director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture and is the first African American and first historian to serve as head of the Smithsonian. His words on the discovery of the Clotilda were: "One of the things that’s so powerful about this is by showing that the slave trade went later than most people think, it talks about how central slavery was to America’s economic growth and also to America’s identity".

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Other Important Historical Discoveries Of The Slave Trade

There have been several other recent important historical discoveries made pertaining to the slave trade in the United States. Let's examine some of these and how they provide a more complete picture of a history that's often forgotten or glossed over in history classes across the country.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

A Slave's Tag In Charleston, South Carolina

A small diamond-shaped piece of metal was handed to archaeology professor Jim Newhand at the College of Charleston. He knew almost immediately what it was: a slave's tag. These small pieces of metal were often used by slave owners as a permit, indicating that the enslaved person had been registered with the city to work for someone else.

The New York Historical Society, Getty Images

The New York Historical Society, Getty Images

Found On A Site Due To Be A Solar Pavilion

The United States Department of Energy and the South Carolina Energy Office wanted to build a solar pavilion at 63 1/2 Coming Street, but it required a "cultural resource survey" of the site before construction could begin.

George N. Barnard , Wikimedia Commons

George N. Barnard , Wikimedia Commons

A Key Insight Into Charleston's History With Slavery

While most places throughout the United States do not want to think about their association with the awful crime of enslaving human beings, discoveries like that of the tag called into question Charleston's relationship with slavery and opened up space for conversation.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

What Did A Slave's Tag Contain?

Slave's tags contained which occupation the person was there to perform and the name of the slave owner. The discovery was unusual because the tag was "in context", or in the place where the person that took it off had left it, rather than being in the hands of collectors, as is so often the case with relics of yesteryear.

The New York Historical Society, Getty Images

The New York Historical Society, Getty Images

Other Findings At The Site

Other findings at the site included the property records for the kitchen, including who may have been enslaved there. According to Grant Gilmore, associate professor in Historic Preservation at Charleston College, "An enslaved person living in the house may have discarded the tag in the hearth or someone on loan from across town may have lost it one day".

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

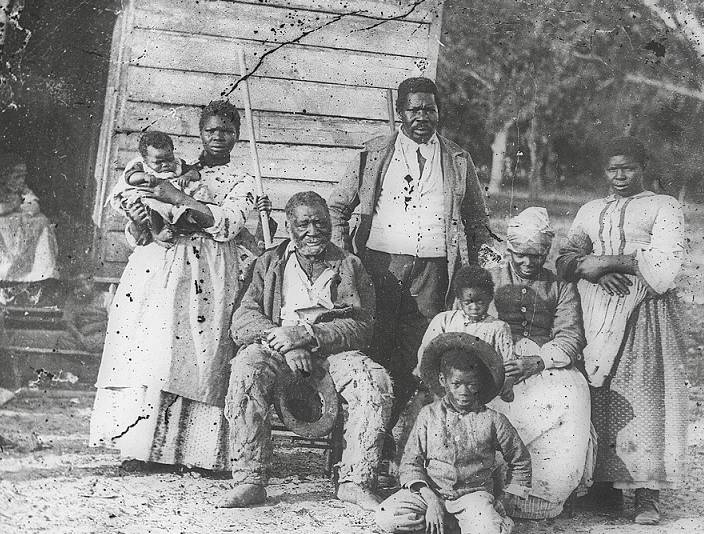

You Felt The Evil

Even though the slave's tag was granted as permission to move about somewhat freely between the person who had loaned the enslaved person and their slave master, the tag was still a mark of enslavement. "You felt the evil," stated Newhard.

Timothy H. O'Sullivan, Wikimedia Commons

Timothy H. O'Sullivan, Wikimedia Commons

The Appalling Tale Of Ernie Franklin, The Rejected Diver

Ernie Franklin was a lifeguard at a pool in Detroit nearly 50 years ago. Ernie now works with the Diving With Purpose Project, an initiative enabling African American divers to go on archaeological dives and discover their history. Diving With Purpose was one of the agencies involved in the hunt for the Clotilda. Franklin had initially wanted to become a diver. He was rejected by the diving school. Why? He was African American.

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

The So-Called "Facts" Offered By The Diving School

The local YMCA in Detroit that he wanted to attend denied him entry, providing so-called "facts" as reasoning: "You know, your lung capacity was too small, your bone density was too thick, and being able to comprehend the physics of the sport would be more of a challenge". Of course, none of this was true, it was just a series of appalling excuses for their racism.

National Geographic, Drain the Oceans (2018-)

National Geographic, Drain the Oceans (2018-)

Franklin Never Gave Up

Despite the appalling racism he faced, Franklin never gave up. He became a qualified diver (eventually) and is now a youth coordinator with the DWP, encouraging a new generation of African American divers. That is, when he's not diving for archaeological history in Florida.

A Forgotten History, Forever Remembered

The discovery of the Clotilda is a vindication of sorts for Woods: " So many people along the way didn’t think that happened because we didn’t have proof. No matter what you take away from us now, this is proof for the people who lived and died and didn't know it would ever be found".

You May Also Like:

Liberating Facts About Harriet Tubman, The American Emancipator

The World's Deadliest Natural Disasters

The Kazakhs: Nomads Of The Steppe

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship, Shipwrecks of America, National Geographic

Sources: