North America's Mammoths

What really made North America's largest animals to vanish? This is a tale buried in permafrost and the clues are scattered across time. Thanks to a new scientific twist, we may be close to an answer.

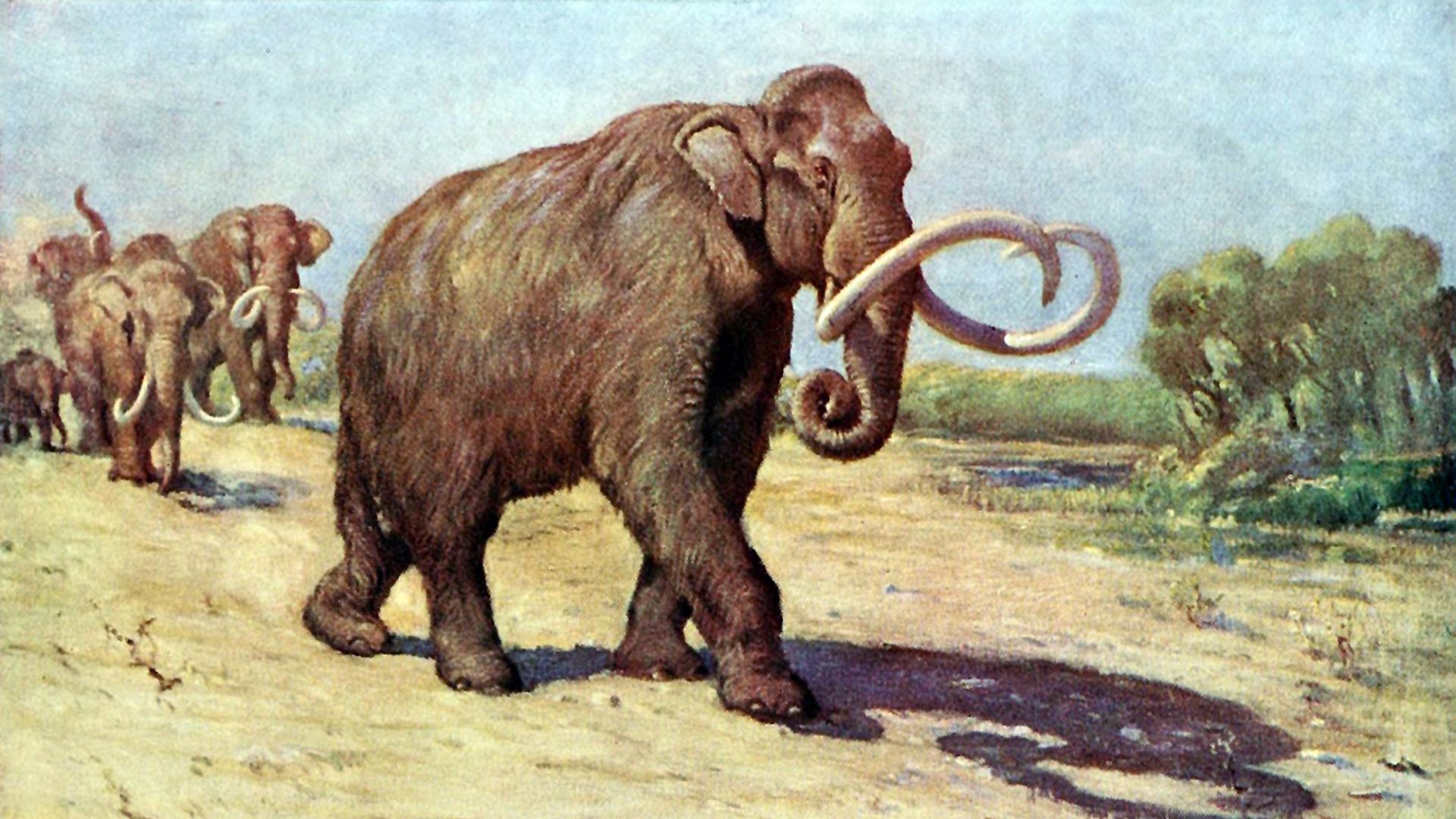

When The Giants Ruled The Continent

Before humans ever set foot on North American soil, massive creatures dominated the land. Mammoths towered over the plains, and saber-toothed cats lurked in the shadows. It was their world. So, what changed? That's the puzzle paleontologists have been piecing together, one ancient bone at a time.

Flying Puffin, Wikimedia Commons

Flying Puffin, Wikimedia Commons

A Land Of Behemoths And Bison

North America once hosted some of the biggest mammals to ever live, including 8-foot-tall camels and wolves twice the size of modern ones. It sounds mythical, but it's all real. Fossil records across the US prove these creatures didn't just exist—they thrived for thousands of years.

uncredited National Park Service (NPS) artist, Wikimedia Commons

uncredited National Park Service (NPS) artist, Wikimedia Commons

The Chill Before The Vanish

The Ice Age shaped and changed everything. During this frigid period, glaciers expanded and habitats stretched into new territories. But then things started to shift. As temperatures slowly climbed, ecosystems began changing faster than some animals could handle. Could warming weather alone explain the megafauna's disappearance?

What's In The Ice?

Glacial cores pulled from places like Greenland preserve tiny particles that tell huge stories. Layers of dust and volcanic ash hint at what was happening in Earth's atmosphere thousands of years ago. But here's the twist: the ice reveals patterns, not clear answers.

Konstantin Papushin, Wikimedia Commons

Konstantin Papushin, Wikimedia Commons

Arrival Of The First Footsteps

Roughly 20,000 years ago, the first humans are believed to have crossed into North America, possibly via the Bering Land Bridge. They arrived in a land full of slow-moving, oversized prey. Coincidence? Maybe. But their timing lines up suspiciously well with the start of the megafauna's decline.

Did Hunters Seal Their Fate?

The Clovis people left some clues. Some archeologists believe that early hunters helped drive mammoths and mastodons to extinction through overhunting. Known as the "overkill hypothesis," this idea has sparked decades of debate. Critics argue the populations were too large to vanish from hunting alone.

10,000 BC (1/10) Movie CLIP - The Mammoth Hunt (2008) HD by Movieclips

10,000 BC (1/10) Movie CLIP - The Mammoth Hunt (2008) HD by Movieclips

The Great Debate Begins

Blame the climate. Blame the humans. Blame the stars. For decades, scientists have argued over what really ended the age of megafauna in North America. Some say extinction was a slow decline, others claim it happened almost overnight. And with every new fossil discovery, the conversation shifts again.

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Bones Tell No Lies

Ancient skeletal remains don't talk, but they don't lie either. They're the hard evidence scattered in caves, buried in tar pits, or locked beneath layers of sediment. Through radiocarbon dating and careful excavation, scientists have been able to create a rough timeline of when and where species disappeared.

Kostyantyn Skuridin, Shutterstock

Kostyantyn Skuridin, Shutterstock

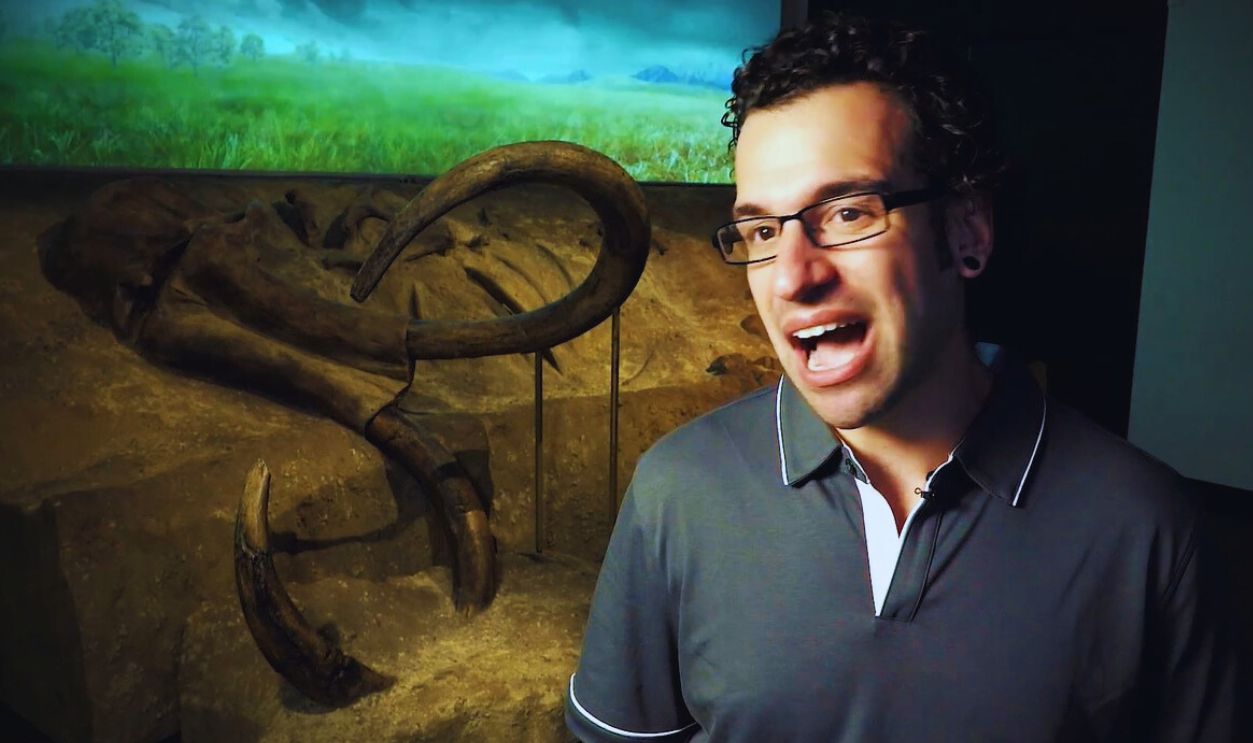

A Museum's Dusty Secret

Walk through the back halls of the Smithsonian or any major natural history museum, and you'll find boxes of old remains. Many of them have sat untouched for decades, too fragmented to study with traditional methods. Inside the drawers, scientists are finding clues that could shift the entire extinction timeline.

Alex Proimos from Sydney, Australia, Wikimedia Commons

Alex Proimos from Sydney, Australia, Wikimedia Commons

The Long-Lost Messenger

Most people think DNA is the only way to study the past, but collagen tells its own story. This tough, fibrous protein can survive in bones far longer than genetic material. What makes it special is its subtle variation between species.

Louisa Howard, Wikimedia Commons

Louisa Howard, Wikimedia Commons

Why DNA Isn't Enough

DNA gets a lot of credit in ancient science, but it has limits. It breaks down quickly, especially in hot or acidic soil. That's why so many ancient skeletal remains yield little or no genetic material. Protein, on the other hand, hangs on longer. It's less detailed than DNA but more durable.

Genetic Breadcrumbs In Collagen

Every species has a unique protein signature, like a hidden ID tag left behind in its bones. Collagen, the most common of these proteins, carries subtle variations that act like genetic breadcrumbs. By analyzing the differences, scientists can match even fragmented fossils to specific groups. Such breadcrumbs help trace migration patterns and extinction timelines.

Scotwriter21, Wikimedia Commons

Scotwriter21, Wikimedia Commons

ZooMS And The Hidden Barcode

One of the most exciting techniques in biomolecular archeology today is ZooMS—short for Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry. It might sound like something from a sci-fi lab, but it's surprisingly simple. Tiny samples of bone are analyzed for protein fingerprints. Even if the bone is unrecognizable, the protein tells the tale.

What is zooarchaeology? Animal bones and the human past. by Everick

What is zooarchaeology? Animal bones and the human past. by Everick

Cracking Open A Mammoth Mystery

For decades, mammoths have stood at the center of the extinction debate. Those shaggy, tusked titans were once everywhere from Alaska to Mexico. But their disappearance wasn't uniform. Some vanished quickly, while others survived on isolated islands for thousands of years. What caused this uneven exit?

From Tundra To Time Capsules

The icy plains where mammoths and other megafauna once roamed have become nature's storage lockers. Frozen soil, known as permafrost, preserves everything from bones to ancient dung. The time capsules offer snapshots of ecosystems long gone. In recent years, thawing permafrost has revealed remarkably intact remains.

NPS Climate Change Response, Wikimedia Commons

NPS Climate Change Response, Wikimedia Commons

The Ground Sloth That Vanished

A creature the size of a car, covered in fur, with long claws for stripping branches. That was the ground sloth, and it was native to North America. These slow-moving browsers seemed built to endure, yet they disappeared with many of their oversized peers. Why did they fail to adapt?

Camels Taller Than Horses

Believe it or not, North America once had its own native camels. They weren't desert survivors like the ones we picture today. They were tall and roamed open grasslands. Fossils show they were widespread before the megafaunal collapse. Their disappearance is often overlooked in extinction discussions, but it raises questions.

When Beavers Were Giants

Today's beavers are impressive builders, but their ancestors were true titans. The extinct giant beaver, Castoroides, grew over seven feet long and weighed hundreds of pounds. It lived in lakes and wetlands across North America by shaping its environment just like its modern cousins. But something disrupted that balance.

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

The Saber-Tooth's Last Stand

Few animals spark the imagination, like the saber-toothed cat. With its muscular build and curved fangs, it looked like it should have ruled forever. But even such apex predators disappeared. Was it starvation as prey vanished? Or something entirely unexpected?

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Bison On The Brink

Bison didn't just vanish during the 1800s. Ancient bison species were once far larger and more widespread than the ones we know today. Their fossils are found across the continent, suggesting they played a huge role in Ice Age ecosystems. Some species disappeared completely, while others adapted and survived.

Robert Pawlicki, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Pawlicki, Wikimedia Commons

Ice Retreat, Life Retreats

As glaciers melted at the end of the Ice Age, North America changed in ways animals couldn't predict. Grasslands shifted. Forests grew where there were once open plains. Rivers moved and new climates emerged. For some species, the changes happened too fast.

scott1346 from Mechanicsville, MD, USA, Wikimedia Commons

scott1346 from Mechanicsville, MD, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Climate Chaos And Shifting Forests

After the Ice Age, temperatures didn't just rise steadily. They jumped and dropped to twist the natural world into unfamiliar shapes. Open grasslands turned into dense forests and water sources dried up or moved. However, climate change alone might not explain every extinction.

Survival In Pockets Of Time

Some species lingered in isolated regions long after their cousins disappeared elsewhere. On islands and remote plains, pockets of megafauna endured for centuries. These holdouts complicate the idea of a single extinction event. Instead, the collapse may have played out in phases, shaped by geography and weather patterns.

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

The Puzzle Of Patchy Extinction

Why did some animals vanish quickly while others hung on for thousands of years? This inconsistency is one of the trickiest parts of the extinction mystery. Scientists call it "asynchronous extinction," and it means it didn't happen all at once or everywhere. That patchy timeline suggests a mix of causes.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

When Extinction Leaves No Single Cause

Some stories don't have clean endings. The extinction of North America's megafauna doesn't point to one clear villain. Like threads in a web, several factors overlap and blur. This realization has reshaped how scientists study ancient disappearances. Maybe extinction wasn't a moment but a process.

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Can A Comet Kill A Kingdom?

One theory argues that a comet or asteroid impact may have triggered massive environmental changes. Supporters of the idea point to a layer of dark sediment found across North America, rich in rare elements and tiny glass-like particles. Could a cosmic event have caused wildfires or disrupted food chains?

The Extraterrestrial Hypothesis

The extraterrestrial hypothesis suggests that a comet impact caused abrupt climate chaos. Supporters cite evidence like nano-diamonds and unusual carbon layers in ancient soil. Critics argue the data is inconclusive. Whether the sky played a role or not, the theory keeps returning.

Diseases From The Dark

Researchers wonder if ancient megafauna fell victim to a mysterious disease—possibly introduced by early humans or animals that migrated with them. Fossil records don't easily reveal plagues, but sudden population drops suggest something more than slow ecological change. It's a chilling possibility as the remains show no signs of trauma.

The Carbon Clock Ticks On

Radiocarbon dating changed how scientists study extinction. By measuring the decay of carbon isotopes in ancient remains, researchers can estimate when an animal died. This technique has exposed gaps in earlier assumptions and helped link extinctions to events like climate shifts and human arrival. But it's not flawless.

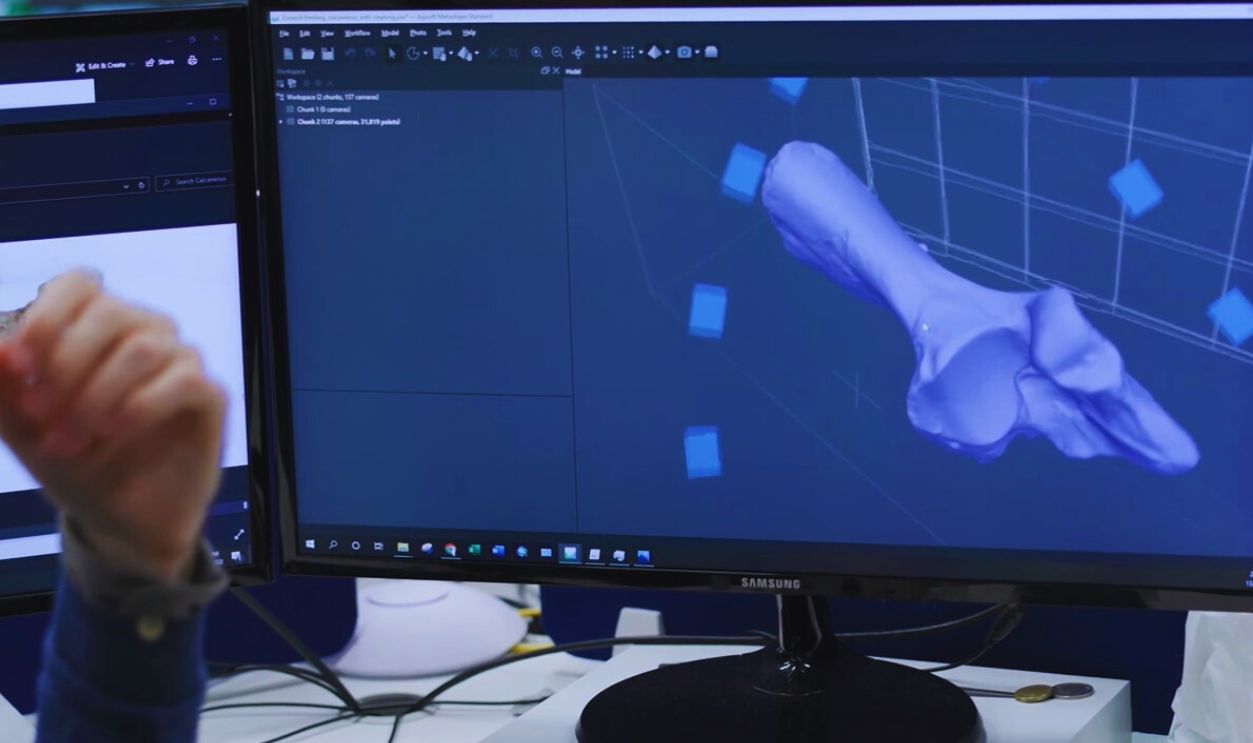

Old Bones, New Stories

A single fragment of bone might look like junk to most people, but to paleontologists, it can open an entire chapter of history. With new tools, even long-ignored fossils are revealing surprising details, like the presence of species in places they weren't thought to exist. These discoveries reshape extinction timelines.

Laser scanning Ediacaran fossil Charniodiscus by Emily Mitchell

Laser scanning Ediacaran fossil Charniodiscus by Emily Mitchell

The Smithsonian's Hidden Vault

Beneath the polished exhibits of the Smithsonian lies a different world. Shelves packed with boxes fill storage rooms few visitors ever see. Some of these remains were excavated nearly a century ago and forgotten. But now, paleontologists are returning to these overlooked collections with fresh questions and better tools.

The genes that make a woolly mammoth a woolly mammoth by UChicago Medicine

The genes that make a woolly mammoth a woolly mammoth by UChicago Medicine

A Past Stored In Plaster

In the early days of excavation, skeletal remains were often wrapped in heavy plaster jackets to protect them. Some of these bundles haven't been opened since the 1930s. Inside, fragile remains sit, waiting for careful hands and modern tools. As museums revisit, these plaster casings are finally being studied.

Preparing Dinosaur Fossils Inside AMNH by American Museum of Natural History

Preparing Dinosaur Fossils Inside AMNH by American Museum of Natural History

Forgotten Finds From 1934

In 1934, archaeologists digging in Colorado unearthed a trove of ancient bones. At the time, they cataloged what they could and boxed up the rest. Those fragments sat in storage for decades, too worn and incomplete for analysis. Today, with ZooMS, they are telling new stories.

Reconstructing The Lost World

By piecing together fossil clues, rebuilding ancient ecosystems is possible: what animals lived where and how they interacted. These reconstructions reveal a vibrant and interconnected world, not just isolated giants. Each new bone adds a brushstroke to this prehistoric canvas.

How To Read Broken Bones

A broken bone can speak volumes. Scientists examine everything from microscopic wear patterns to protein residue to determine what animal it came from. Even the way a bone fractured can suggest how it was buried or what conditions it faced. These clues help researchers build timelines.

When They Refuse To Speak

Some fossils simply won't cooperate. They're too degraded or too altered by time. Even with modern tools, there are cases where species remain unidentified and timelines incomplete. These silent bones remind researchers that not every question has an answer, at least not yet.

Etemenanki3, Wikimedia Commons

Etemenanki3, Wikimedia Commons

Museum Collections Reimagined

What once sat in quiet storage is now at the center of groundbreaking research. Museum collections are being reimagined as dynamic sources of new information. Even bones collected a hundred years ago are finding fresh relevance. These are the key to rewriting everything we thought we knew.

JJonahJackalope, Wikimedia Commons

JJonahJackalope, Wikimedia Commons

Tiny Fragments, Big Revelations

Sometimes, all it takes is a bone fragment to shake up the story. The pieces, once too damaged to be useful, are revealing species and extinction dates. They used to be dismissed as unidentifiable junk but now carry weight. In extinction science, size no longer matters.

Emőke Dénes, Wikimedia Commons

Emőke Dénes, Wikimedia Commons

What ZooMS Really Tells Us

ZooMS is changing how researchers approach the past. By identifying species from bones once thought too damaged to study, it fills gaps in the fossil record. It can confirm or challenge earlier identifications and shed light on regional extinction patterns. ZooMS is not perfect, but it's fast and precise.

What is zooarchaeology? Animal bones and the human past. by Everick

What is zooarchaeology? Animal bones and the human past. by Everick

Building A Megafauna Library

To fully benefit from ZooMS, paleontologists are creating protein reference libraries. The collections catalog the collagen patterns of known species to identify unknown samples. But there's still a long way to go. Many North American megafauna don't yet have complete profiles. Building this library is slow work but essential.

What Bones Say About Us

Studying ancient animals is also a way of studying ourselves. How did humans affect ecosystems? What role did our ancestors play in extinctions? Hunting marks and migration shifts help trace the impact of early human behavior. In many ways, the bones reflect our history as much as theirs.

Tim Evanson from Cleveland Heights, Ohio, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Tim Evanson from Cleveland Heights, Ohio, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Lessons From The Giants' Fall

The disappearance of North America's megafauna is a warning. Climate change and habitat loss still shape the world today. Studying such extinctions helps us understand how ecosystems respond to rapid change. More importantly, it shows how fragile survival can be.

Funding The Forgotten

Behind every breakthrough is a budget. And when the money runs short, museum collections and quiet research projects are often the first to suffer. Yet the overlooked bones and storage drawers hold answers to some of science's biggest questions. Without proper funding, valuable materials risk being lost or discarded.

Nils Knotschke, Wikimedia Commons

Nils Knotschke, Wikimedia Commons

The Case For Curating The Past

Preserving bones and excavation records may not seem urgent, but without them, future discoveries don't happen. Curation ensures that every specimen—no matter how small—has a chance to contribute. The case for curating the past is simple. Without it, we risk losing the future's most important clues.