The People History Forgot To Mention

In the vast lands of Central Asia and Eastern Europe, you’ll find some of the world’s most fascinating and little talked about nomads: The Kazakhs.

From their ancient origins to their more contemporary encounters with outsiders, the story of the Kazakh people is one of resilience and deep connection to the land around them.

Where Do They Live?

The Kazakhs are part of the Turkic ethnic group, with much of their population living in the Ural Mountains that stretch across Russia and Kazakhstan. They can also be found in parts of China, Mongolia, and Uzbekistan.

Altaihunters, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Altaihunters, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

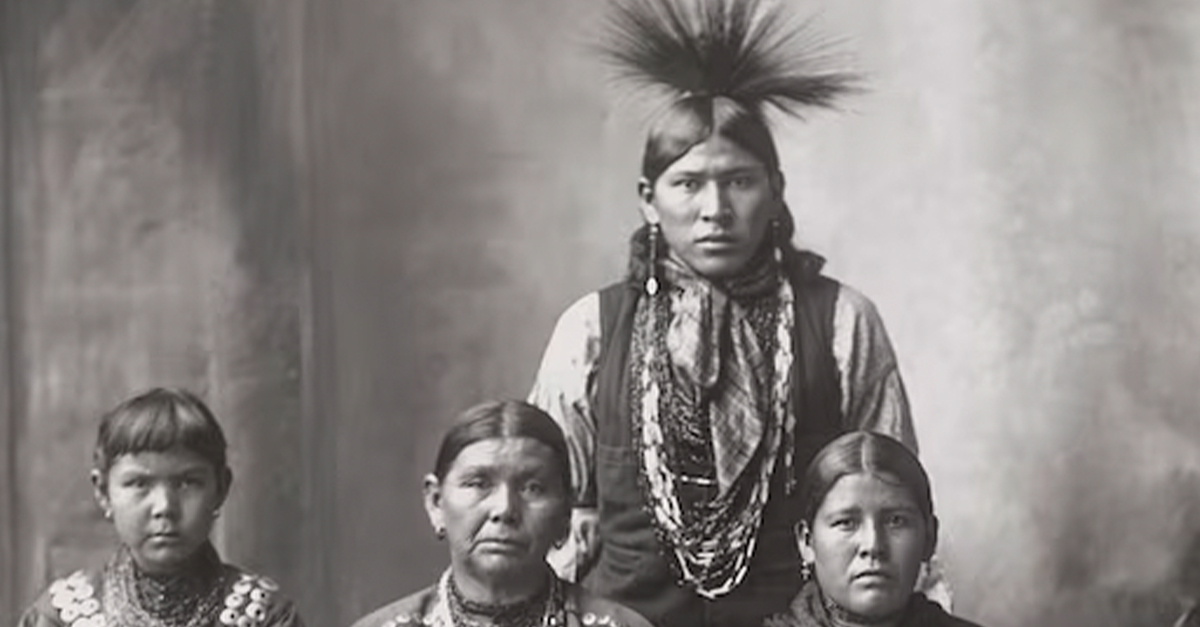

Two Cultures Become One

The history of the Kazakhs is a long one, beginning in the 15th century. That’s when medieval Turkic tribes joined with Mongolian tribes who had ancestral roots tracing back to the Mongol Empire.

What’s In A Name?

The name “Kazazh” refers to ethnic group, while all citizens of Kazakhstan are called “Kazakhstani” regardless of their ethnic background.

Symbat Bolatova, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Symbat Bolatova, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Their Ancestors

Archaeological, linguistic, and genetic research suggests that the Kazakhs’ Turkic ancestors descended from communities who migrated from Northeast China to Mongolia in the 3rd century BCE.

By the 1st century BCE, they had transformed from pastoral communities to equestrian nomads on the steppes of Central Asia.

As The Seasons Change

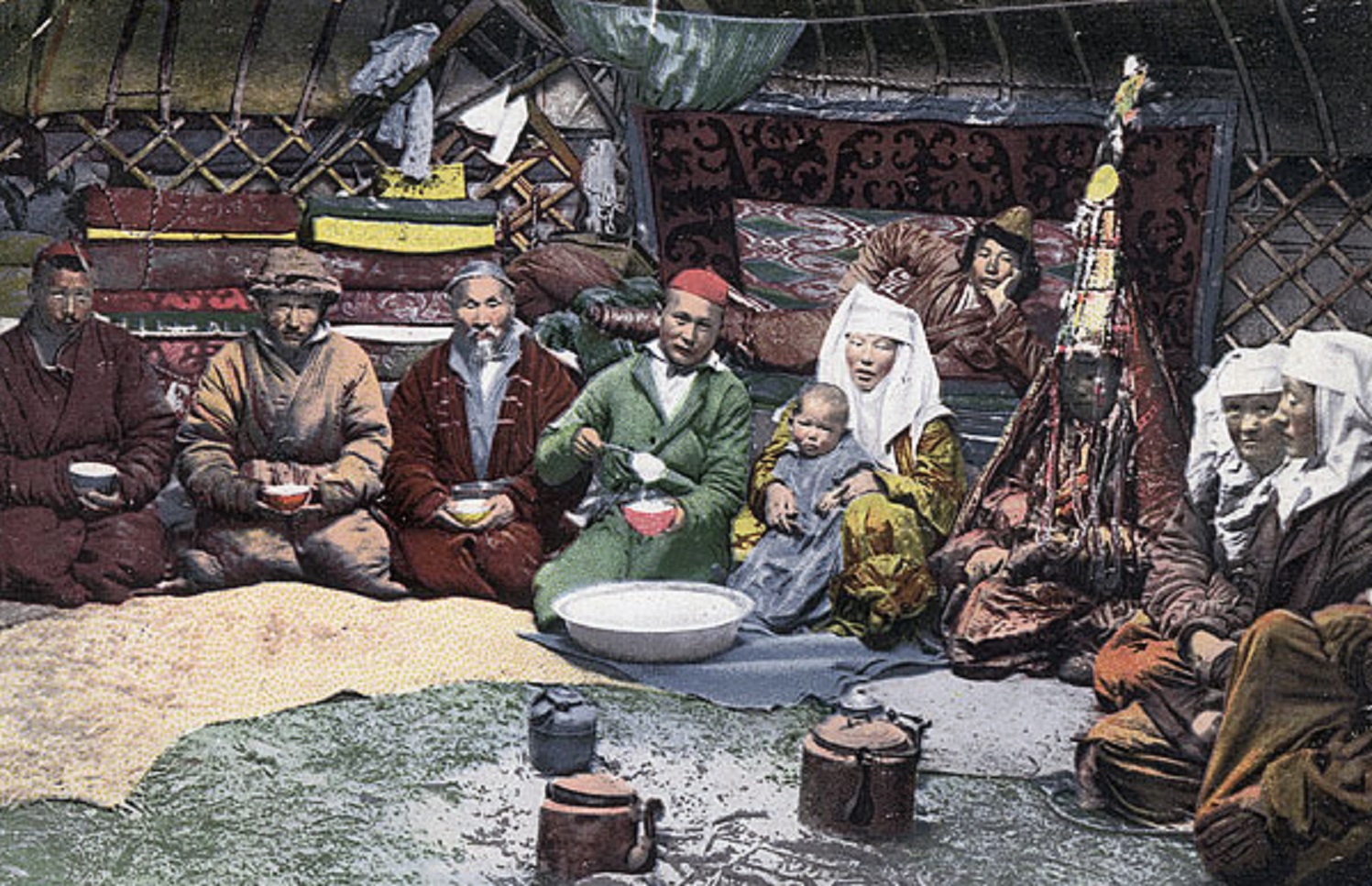

As part of nomadic life, the Kazakhs would migrate each season to find new grazing grounds for their livestock. Many Kazakhs owned horses, but cows, sheep, goats, and even camels were common livestock animals.

Дудин С. М., Де-Лазари Константин Николаевич. Wikimedia Commons

Дудин С. М., Де-Лазари Константин Николаевич. Wikimedia Commons

Their Houses

The early Kazakhs lived in dome-shaped tents called yurts. The yurts were portable and made of wooden frames that were covered with felt or hides. In the 19th century, many Kazakhs began to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle, though there are still many nomads in Mongolia.

cea +, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia CommonsA Kazakhstani's Best Friend

cea +, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia CommonsA Kazakhstani's Best Friend

Eagle Hunting is one of the Kazakhs’ most famous traditions. There are thought to be 250 eagle hunters among the Kazakhs in Bayan-Ölgii Province.

Commanding these powerful predators, they can hunt a variety of wildlife, including hares and foxes.

Поляков И. С. , Дудин С. М., Wikimedia Commons

Поляков И. С. , Дудин С. М., Wikimedia Commons

The Backup "Eagle"

The Kazakhs are known for hunting with golden eagles, but in the absence of their preferred hunting partner, pretty much any bird will do. Peregrine falcons, goshawks, and saker falcons are among the many bird species that have been trained by Kazakh hunters.

www.david baxendale.com, Flickr

www.david baxendale.com, Flickr

The Grand Competition

The Golden Eagle Festival, held every year in Mongolia, is the perfect chance to witness Kazakh eagle hunters in action. To celebrate their heritage and show off their skill, hunters dress up in their traditional regalia, get atop their best horses, and compete in competitions that test their speed, accuracy, and agility.

Gabideen, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Gabideen, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Something For Everyone

Eagle hunting isn’t the only thing on showcase at the Golden Eagle Festival. Other fun events include archery, horse racing, and Bushkashi, horseback tug-of-war that’s played with a goatskin.

Gabideen, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Gabideen, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Kazakhstani Girl Power

Like in many ancient cultures, Kazakh women have faced some inequality when it comes to cultural expectations. Though they have long been known to train eagles for hunting, the Golden Eagle Festival was a boys-only club for many years. That all changed in 2016. That year, 13-year-old Aisholpan was the first female to not only enter the competition but win it.

Female competitors are still a rare sight at the festival, but Aisholpan’s win was documented in the 2016 film, The Eagle Huntress.

Gabideen, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Gabideen, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

No Going Back

The eagle hunters have become a fascination with tourists from around the world. Seeing how lucrative this can be, the government of Kazakhstan has tried to entice the eagle hunters to return to their native homeland, but most have chosen to stay in Mongolia.

Gabideen, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Gabideen, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Ancestors Are Holy

The early Kazakh people believed in shamanism and the worship of their ancestors. They also engaged in the worship of natural elements like the sky and fire, and believed in supernatural forces like good and evil spirits. Many people wore special talismans or beads to protect themselves from evil.

These shamanistic beliefs are still a strong part of Kazakh culture.

Ceyhun Kavakci, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ceyhun Kavakci, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Shamans

Kazakh shamans are called bakhsy and a believe in their divine strength is a large part of Kazakh culture. Both men and women can be shamans, and their rituals are typically accompanied with music from a large violin-like string instrument.

Hearts Of Gold

Kazakh people are known for their kindness, and there are many traditions that are based on the importance of hospitality in their culture. Konakasy, a welcoming tradition where guests are given food and entertainment, and Suinshi, the tradition of giving a gift to someone who brings good news, are just two examples of heartwarming Kazakh traditions.

Altaihunters, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Altaihunters, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Tunes That Make Them Move

Like any culture, music is important to the Kazakhs. Traditionally, they've enjoy making music with the dombra, a two-stringed lute, and the kobyz, a bow instrument. Both are important elements of any traditional Kazakh orchestra.

Popolon, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Popolon, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Rely On Their Animals

Livestock is the key to survival for the Kazakh people. For one, their diet is mostly made up of mutton and milk. Fermented mare’s milk and horse meat (called koumiss) are also particularly valuable.

In addition to providing food, though, the Kazakh people derive many of the products they use in their daily lives from their livestock. Horsehair is used to make rope, while hides and horns from sheep are used to make utensils and clothing.

Kazakh Cuisine

The way the Kazakhs cook has also been influenced by their nomadic history. Many common ways of preparing food are meant to preserve the food for a long time. Dried, salted meat is a common Kazakh snack, and their preference for fermented milk is linked to how well the nomads were able to save it.

Altaihunters, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Altaihunters, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

What's Their Favorite Dish?

Besbarmak is the most popular Kazakh meal. It is made of boiled mutton or hose meat and is often served with shorpa, a meat broth, and pasta. Horse meat sausages called shuzhuk and rice pilaf with vegetables and chunks of meat are also common Kazakh dishes.

Sara Yeomans, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sara Yeomans, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

What They Wear

Much like the type of food they consumed, the Kazakh's traditional clothing was tailored toward helping them survive the harsh realities of their nomadic lives. They made consistent use of animal furs and hides, including felt from sheep's wool or camel hair. To add some extra flair, they wore jewelry made from animal horns and hooves, as well as bird beaks.

Encik Tekateki, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Encik Tekateki, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Never Forget Where They Came From

Many pastoral Kazakhs or those who embrace a more modern lifestyle tend to wear Western clothing. However, they still dig out their traditional clothes for special occasions and holidays.

They Love Their Horses

Horses have always had a special place in Kazakh culture. As well as being used for food, they serve important roles in transportation and farming.

The Mongol horse is a common breed in Kazakh stables, though they easily get confused for ponies due to their small size.

www.david baxendale.com, Flickr

www.david baxendale.com, Flickr

The Three Hordes

Though tribalism plays much less importance in Kazakh culture than it used to, knowledge of one’s ancestral tribe and asking others about their own is still a common tradition among the Kazakhs. Each tribe belongs to one of three hordes (also called jüz): the Senior, Middle, or Junior horde.

The Father Of The Hordes

The Kazakh believe that they are descended from one forefather. According to their legends, this great ancestor had three sons and when he died, they divided his territory and formed the three hordes.

Airunp, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Airunp, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Senior Horde

The three hordes are still a tradition among modern Kazakhs, with each representing its own territory (though there is no hostility between the hordes). Known records of the Senior horde date back to 1748, and this horde’s vast territory includes southeastern and southwestern Kazakhstan, northwestern China, and some parts of Uzbekistan. Many famous Kazakhs and those among the governing elite are part of the Senior horde.

Aralim, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Aralim, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Smaller Hordes

The Middle horde covers north, central, and eastern Kazakhstan and is made up of six tribal groups. Only three tribes are part of the Junior horde, and it covers western Kazakhstan and Russia.

Поляков И. С. , Дудин С. М., Wikimedia Commons

Поляков И. С. , Дудин С. М., Wikimedia Commons

Speaking Their Piece

Like many nomadic cultures, the Kazakhs have maintained an incredible oral history that dates back centuries. Poetry and songs are the most popular ways of telling stories, which are often about legendary Kazakh heroes. In modern times, their oral tradition has been used to share revolutionary ideals and retain a sense of pride in Kazakh culture.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/kjfnjy/, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

https://www.flickr.com/photos/kjfnjy/, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Changed Their Beliefs

Unlike the earliest Kazakh people, many currently follow Islam. In the 8th century CE, Arab missionaries brought their beliefs to the Kazakhs for the first time. In 1936, when the Soviet Union seized control of Kazakhstan, they used the Muslim traditions and institutions to push the Kazakhs to assimilate to Communism.

Petar Milošević, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Petar Milošević, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Respecting The Past

While many Kazakh people identify as Muslim, the devotion to Islam is even stronger among the villagers who lives in Kazakhstan’s countryside. In those communities, people who are thought to be descended from the 8th-century missionaries are given a lot of respect.

A New Home

During the Soviet era in Kazakhstan, much of the Kazakh population fled to Mongolia, where they were free to embrace their nomadic lifestyle and traditions. Many Kazakhs now call Bayan-Ölgii Province home.

Sergei Ivanovich Borisov, Wikimedia Commons

Sergei Ivanovich Borisov, Wikimedia Commons

The Language

The Kazakh language is part of the Kipchak (meaning “Northwestern”) family of Turkic languages. It is written using Arabic script, but over the years there have been attempts to change the written form of Kazakh as a means of controlling and punishing the Kazakh people.

Поляков И. С. , Дудин С. М., Wikimedia Commons

Поляков И. С. , Дудин С. М., Wikimedia Commons

They Fought For Their Roots

In the mid-19th century, Kazakh poets educated in Muslim colleges spearheaded a revolt against Russian domination in Kazakhstan. In response, the Russian authorities developed a Cyrillic-based script for the Kazakh language and established a network of secular schools to promote their version of Kazakh culture and identity.

But the plan didn’t unfold as they had hoped.

Russischer Photograph um 1900, Wikimedia Commons

Russischer Photograph um 1900, Wikimedia Commons

Just A Phase

People weren’t a fan of the new Cyrillic version of the Kazakh language, and despite Russia’s best attempts, it never gained much spread in Kazakhstan. By 1917, using Arabic script for the Kazakh language was back to being the norm throughout the country.

But ten years later, the Kazakhs found their language under attack again.

Shutting Them Down For Good

In 1927, a Kazakh liberation movement began to pick up steam in the Soviet Union. The Soviets quickly shut it down and as punishment, they banned the use of Arabic script for the Kazakh language.

Latin was made the new writing system, but in 1940, the Soviets turned the tables on the Kazakh people once again.

Russischer Photograph um 1900, Wikimedia Commons

Russischer Photograph um 1900, Wikimedia Commons

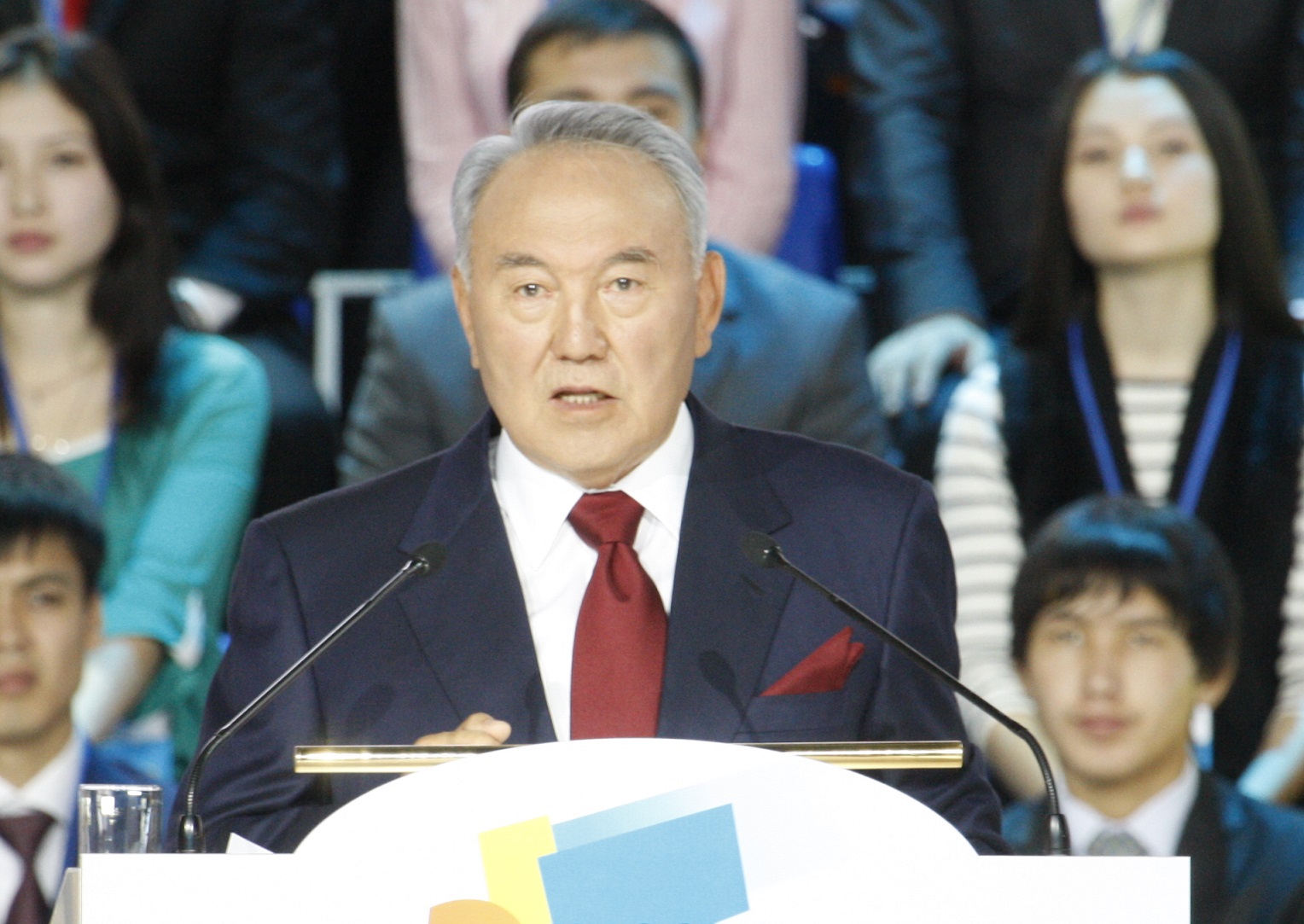

Reclaiming Their Heritage

In 1940, the Soviet government reintroduced the use of the Cyrillic Kazakh alphabet, and it has been used in Kazakhstan and Mongolia since then. But change is on the horizon. In 2017, Kazakhstan’s president ordered that the official script for the language be changed to Latin.

This transition from Cyrillic to Latin is meant to reclaim a part of traditional Kazakh culture that was lost under Soviet rule and should be complete by 2031.