The Chernobyl Disaster Explained

One April night in 1986, the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Soviet Ukraine was in the middle of a safety test when its reactor #4 exploded. When it comes to the disaster, the explanations are practically rocket science, but they're also fascinating—and we're here to explain it piece by piece.

A Flaw In The System

Pre-disaster, the Soviet-built RBMK reactor at Chernobyl had one concerning issue. Even after shutting it down, the massive nuclear reaction would still generate heat—which meant the Soviets needed the reactor’s electrical water system to work reliably to cool it down.

There was, however, a problem with that.

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Question Of Timing

Because the cooling system worked on electricity, the Soviets were worried about what could happen to the reactor during a blackout, which wasn't uncommon in the USSR. While they had back-up generators, these took over a minute to power up and start pumping the masses of water needed to properly control a nuclear reaction.

In short, the Soviets had a huge time gap and a nuclear reactor’s volatility in the middle. So they did the only thing they could.

Suicasmo, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Suicasmo, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Testing The System

In response, the Soviets did—at first—the right thing. They began scheduling tests to work around this problem, hoping they could use the reactor's steam turbine as a kind of ad hoc backup generator. Only, this is where it all began to go wrong. They tried for years to get this to work, but the numbers were never where they needed.

In 1986, that fateful April night, they began their fourth, desperate attempt on Chernobyl's reactor #4. It would end in tragedy.

Paweł 'pbm' Szubert, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Paweł 'pbm' Szubert, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Lowering The Output

In order to conduct the turbine test, the attendants had to partially power down the reactor, which usually worked at 3,200 megawatts (MW) and which they aimed to reduce to 700 MW. The plan was to complete the entire test during the day shift of April 25, lowering the power throughout the day, shutting off the emergency cooling system, and starting the test at 2:15 pm. Then it hit a snag.

Argonne National Laboratory, Wikimedia Commons

Argonne National Laboratory, Wikimedia Commons

Kiev Makes A Call

Just 15 minutes before testing was supposed to start, with the reactor at 50% power capacity and the emergency system off, operators got a call from Kiev requesting that they stop lowering the reactor’s power and pause the test. Why? Electricity was precious in the USSR, and the country needed reactor #4 to be operational for its peak evening demands, which were fast approaching.

Chernobyl agreed, but the tensions must have run high. The decision-making began to get sloppy.

No Emergency System, No Preparation

The next actions at the plant showed how ill-prepared everyone was. For one, they kept the emergency system off for the next 11 hours, even with the reactor running. Then, when Kiev finally called again at 11:04 pm and gave the go-ahead, the day shift personnel originally briefed for the test were long gone.

Instead, the evening shift who had replaced the day shift were also about to leave, and now the night shift—with little warning—had to do the test. No wonder it went so wrong.

ArticCynda, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

ArticCynda, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The People Involved

Overseeing the long-delayed test was Anatoly Dyatlov, deputy chief engineer, as well as shift supervisor Aleksandr Akimov. Joining them was 25-year-old Leonid Toptunov, who oversaw the physical operations of the reactor that night. He had only worked independently as a senior engineer for three months.

Vincent de Groot, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Vincent de Groot, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

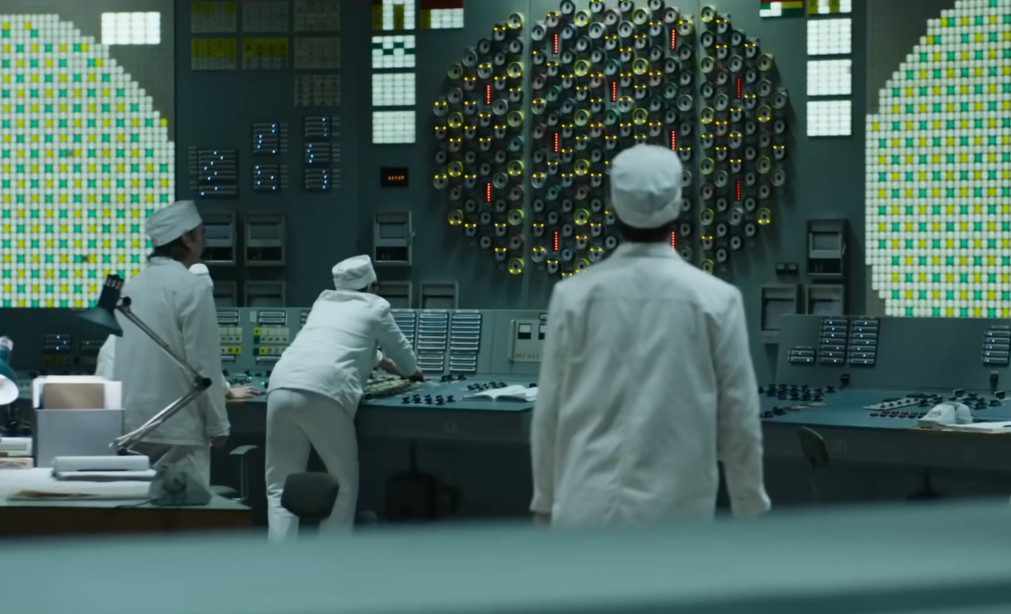

How An RBMK Reactor Works

To understand the disaster that was looming—and just how dangerous things were, even at this point—we have to understand the RBMK reactor inside Chernobyl’s plant that day. The nuclear reaction involved:

The reaction itself

The control rods

The cooling system

The byproducts of the reaction

These four parts built up to doom as the night wore on.

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

How An RBMK Reactor Works: The Reaction

The reactor that day in Chernobyl worked with uranium fuel. As the uranium atoms in the reactor split and then collided with each other, this actually increased reactivity in the nuclear fission reaction.

This is, needless to say, an extremely powerful reaction, and it had to be controlled somehow. Enter: Control rods.

Cs szabo, CC BY-SA 2.5, Wikimedia Commons

Cs szabo, CC BY-SA 2.5, Wikimedia Commons

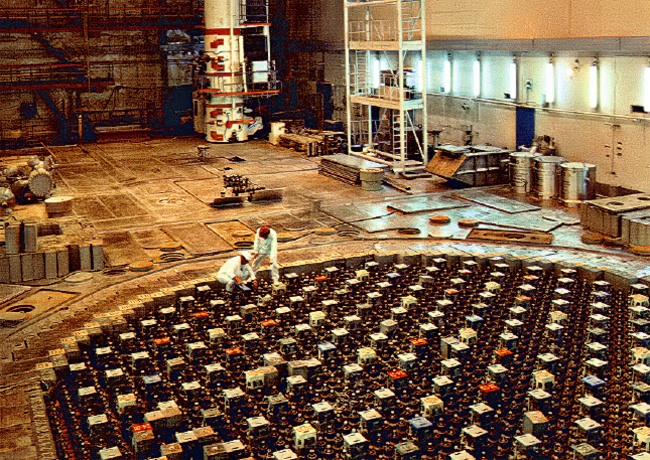

How An RBMK Reactor Works: The Control Rods

The Chernobyl reactor was outfitted with 211 boron “control rods”. These could be partially inserted into the reaction chamber, fully pushed in, or fully taken out. When pushed in, partially or fully, the boron rods would slow down the reactivity.

Many experts find it best to think of the rods as the “brakes” of a nuclear reactor. Push a little, slow down a little. Push a lot, slow down a lot. But there were other failsafes too.

Alexey Danichev, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Alexey Danichev, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

How An RBMK Reactor Works: The Cooling System

The cooling system is the water pumps we've already discussed, but it's more than just water. Coolant water naturally turns to steam as it hits a hot reaction chamber, making the chamber even hotter and thus producing even more steam. But thankfully, nuclear fuel, like uranium, gets less reactive as it rises in temperature, which balances this process out.

But all this balance doesn’t stop potentially harmful byproducts.

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

How An RBMK Reactor Works: The Byproducts

Finally, a nuclear reaction has chemical byproducts. More specifically, as uranium atoms split and release their energy, they make the isotope xenon-135. This is the devil’s handshake of many nuclear reactions: xenon is extremely poisonous, but it also helps cool down and control the reaction. Moreover, it's generally burned off as the normal operations of the reaction go on and the heat continues.

But this is exactly the trouble Chernobyl ran into: They weren’t in normal operations.

Alexander Blecher, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Alexander Blecher, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Xenon Enters The System

Because of the call from Kiev to pause the testing and the long wait to start it back up again, the Chernobyl nuclear reactor had been at half power for hours and hours. As a result, the reaction was active enough to produce xenon-135, but not active enough to burn that xenon off into a more stable isotope. Instead, xenon began sitting in the reactor.

The operators noticed the consequences immediately.

State agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone management, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

State agency of Ukraine on Exclusion Zone management, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Test Can Finally Begin

When Chernobyl got the OK to continue the test, the first thing the operators did was to continue to lower the output of reactor #4 to where they had wanted it early that day. They were successful: They hit 720 MW just after midnight and started to plan their next steps for the test. Then it instantly began to unravel.

AwOiSoAk KaOsIoWa, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

AwOiSoAk KaOsIoWa, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Poisoned Reactor

After reaching this low output, operators noticed that the megawatts kept plummeting, even without them touching anything. They understood in a flash: They had "reactor poisoning," where xenon-135 was sitting, unchanged, in the chamber and cooling the reaction.

To be fair, this was still a situation that the operators could grasp, as it wasn’t entirely uncommon. But the next move was new territory.

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Near Shutdown

Eventually, after the reactor slumped to 500 MW and nothing was raising it, the operators decided they needed to switch on manual control. Except this made things so much worse. Either human error or a faulty system caused a sudden power drop to a minuscule 30 MW, all but shutting down the xenon-filled reactor.

They could have stopped now. They should have stopped now.

Andrzej Karoń, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Andrzej Karoń, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Control Rods Go Away

Remember, inserting boron control rods slows down the nuclear reaction—which means removing them speeds it up. Knowing this and needing a quick fix, the operators began frantically removing control rods from the chamber. It was nearly futile: By 1:00 am, they had only shoved the reactor up to 200 MW.

Inside, though, the reaction was seething.

US Atomic Energy Commission, Wikimedia Commons

US Atomic Energy Commission, Wikimedia Commons

It Goes Seriously Wrong Inside The Reactor

At this point, the entire balance of the nuclear reaction was completely off. It wasn’t hot enough to produce enough steam—and this throws off everything, disrupting the normal reaction cycle outlined above. Nuclear reaction is a dance, and Chernobyl was staggering, stumbling, about to fall.

Oh, and the operators were about to make the exact wrong decision.

They Take The Brakes Off Completely

Faced with the measly 200 MW, Dyatlov and his team decided to perform the scheduled test anyway. It was a horrible idea. When they still couldn't maintain output, they started taking out even more control rods to desperately up it again, xenon poisoning be darned.

In the end, they took out a full 205 control rods out of 211. The reactor was now a vehicle careening down a hill—without brakes.

Justin Stahlman, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Justin Stahlman, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Started And They Finished In Seconds

What happened next has been studied for decades, but parts of it are still unknowable (largely because most of the people in that room are now dead). What we can make out is this: At 1:23:04 am, they started the test in earnest—and exactly 36 seconds later, they pressed the emergency shut down button.

Jason Minshull, Wikimedia Commons

Jason Minshull, Wikimedia Commons

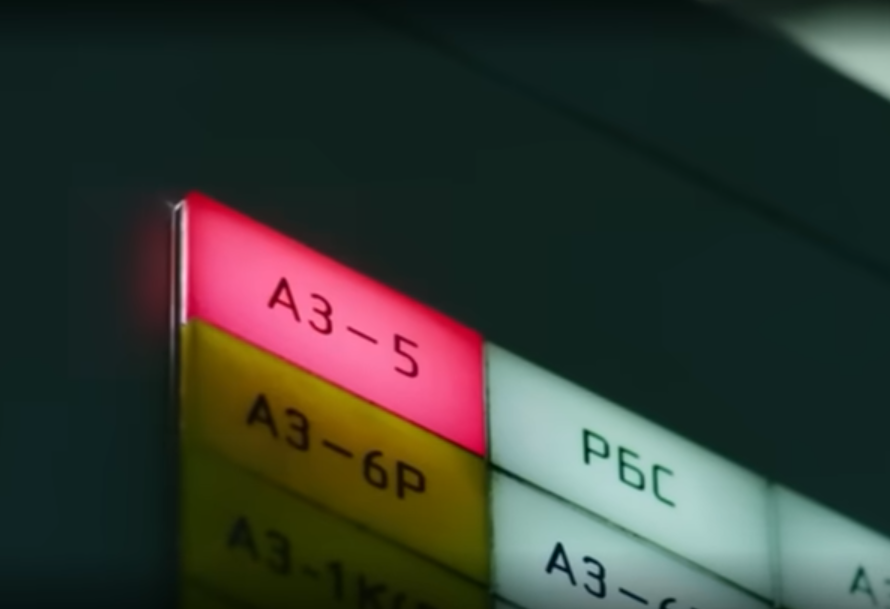

The AZ-5 Button

Called a “scram” in general parlance and the “AZ-5” button at the Chernobyl plant, the emergency shut down button functions in an RBMK reactor by inserting the control rods back into the reactor all at once. To this day, we don’t know exactly why they pressed it, whether it was a planned reset after the test or a genuine reaction to a perceived emergency.

Either way, it was the worst thing they could have done.

The Reactor Was At A Breaking Point

Just before the AZ-5 button was pressed, the stability of the reactor was hanging by a molecule. The control rods were out, the coolant was mostly gone, and the only thing controlling the reaction in the slightest bit was the xenon poison. It was a nuclear tinderbox—and unfortunately, it was the emergency safety button itself that ignited it.

Graphite-Tipped Control Rods

In the end, the control rods had one utterly fatal flaw. The boron rods had been manufactured with graphite tips, and while boron reduces nuclear reactivity...graphite increases it. The Soviets were aware this was an issue, they just never thought they'd see a situation where it mattered and thus didn’t want to spend the money to fix it.

Oh, but it did matter.

The Reactor Sprung To Life

When the AZ-5 button sent a mass of control rods into the now-volatile reactor, the worst possible result occurred: Thanks to the graphite hitting the chamber first, the power skyrocketed.

Any water left in the reactor went instantly to steam, which expanded and ruptured some of the fuel rods. There is a theory that this also jammed the control rods, so that those reactive graphite tips were stuck just peeking out without the benefit of boron, constantly upping the reaction. It was devastating in the blink of an eye.

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

IAEA Imagebank, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

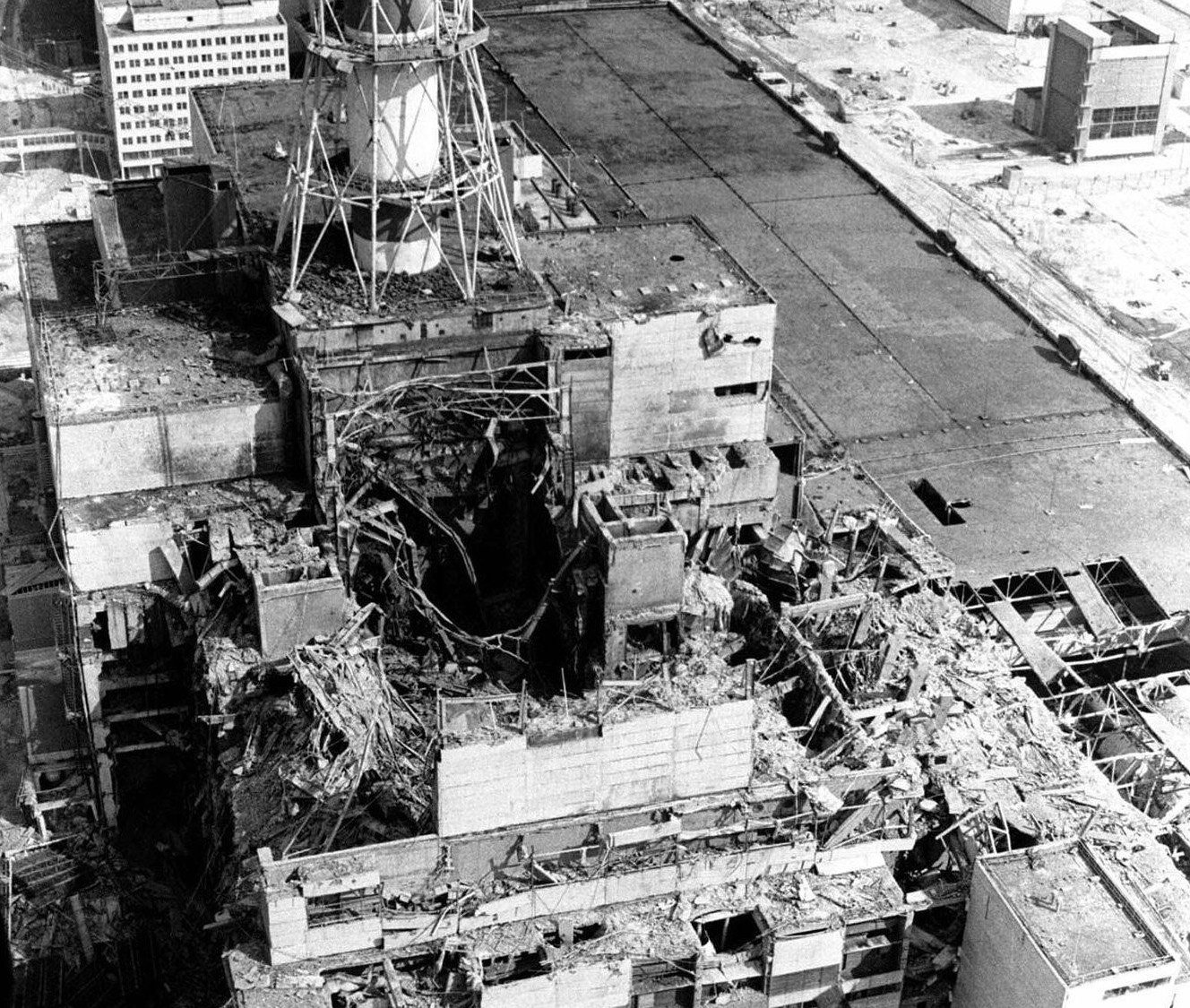

The First Explosion

In seconds, the reactor went to 30,000 MW—10 times its normal output. Or, that’s our best guess. That was just the last reading they could get from the control panel; it could have been 10 times higher than even that.

Those damaged fuel channels then spewed out explosive steam, eventually blowing off the containment vessel around the reactor and then blowing out its roof. But this was just the first explosion.

The U.S. National Archives, Picryl

The U.S. National Archives, Picryl

The Second Explosion

As the nuclear reaction continued, a second, even bigger explosion—equal to roughly 225 tons of TNT—rocked the landscape two or three seconds later. This dispersed the core, more of the containment vessel, and chunks of hot graphite.

Although the shocking nuclear chain reaction ended here, the radioactive fallout now began.

ArticCynda, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

ArticCynda, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Fallout

Graphite fires flared to life now, spreading radioactive fire—but the citizens were completely in the dark. Firefighters arrived on the scene without knowing the reactor explosion had caused the flames, and some even picked up the radioactive graphite with their hands.

Not Asking, Not Telling

Not everyone claimed ignorance that day. Other responders believed they understood the situation immediately. As one recalled, "Of course we knew! If we'd followed regulations, we would never have gone near the reactor. But it was a moral obligation—our duty. We were like Kamikaze”.

Alexander Blecher, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Alexander Blecher, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Delayed Response

The Soviet government received intense criticism about its response to events, and this criticism continues today. Many officials tried to cover up the event completely, and the nearby town of Pripyat wasn’t immediately evacuated. Citizens began experiencing headaches and vomiting within hours.

The Exclusion Zone

36 hours after the accident, the government finally evacuated nearly 50,000 people within a roughly 6-mile radius of the power plant, only later expanding that zone to a 19-mile radius and an additional 68,000 people—many of whom by then were already experiencing the severe effects of radiation.

Alexander Blecher, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Alexander Blecher, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Toll On Human Life

The explosion itself killed two engineers instantly, but that was just the beginning. 237 emergency responders were hospitalized, with over half showing acute radiation syndrome. 28 of those people were dead within three months.

In the next decades, instances of childhood thyroid cancer rose to levels only explained by the disaster, making the total death toll of Chernobyl impossible to calculate and difficult to contemplate. Of course, human life wasn't the only thing lost.

The Toll On Wildlife

The forest downwind of the blasted reactor turned red-brown and then died—it’s still called the “Red Forest”. Moreover, many wild animals in the area either perished or felt other repercussions: domesticated horses left on an island soon died from the destruction of their thyroid glands thanks to radiation, mutation rates increased by a factor of 20, and there were also higher mortality rates and reproduction issues in affected areas.

Jorge Franganillo, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Jorge Franganillo, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Chernobyl Today

Today Chernobyl and the near-by Pripyat remain almost completely abandoned, although some tourists have been allowed in in recent years. Following the disaster, responders also built the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant sarcophagus to contain the radioactive contamination still roiling in the air. It now stands as the Chernobyl New Safe Confinement.

Clean up of the debris is scheduled to be completed only in 2065.

Conclusion

The Chernobyl Disaster looms heavy in human consciousness, a reminder of what happens when we play with forces far beyond our control or complete understanding. Reactor #4 was pushed to the brink, and then beyond that brink. It’s a tragedy we won’t soon forget.

You May Also Like

Haunting Photos From Chernobyl Nearly 40 Years Later

Is Chernobyl's Elephant Foot The World's Deadliest Discovery?

The Worst Nuclear Disaster In History Wasn't Chernobyl

Mattias Hill, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mattias Hill, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sources: 1