Mexico's Warrior Tribe

The Yaqui are known for having waged the most determined, enduring, and successful resistance against forced colonization. In fact, they’re the only Native American tribe that has never officially surrendered to either the Spanish colonial forces, the Mexican government, or the United States.

But while they may have won back their land, they didn’t exactly come out on top. During the early 20th century, much of the Yaqui tribe had been captured and sold to plantations. But slavery wasn’t their rival’s only goal. Yaqui women were forced to marry Chinese men—and the reason why is utterly disturbing.

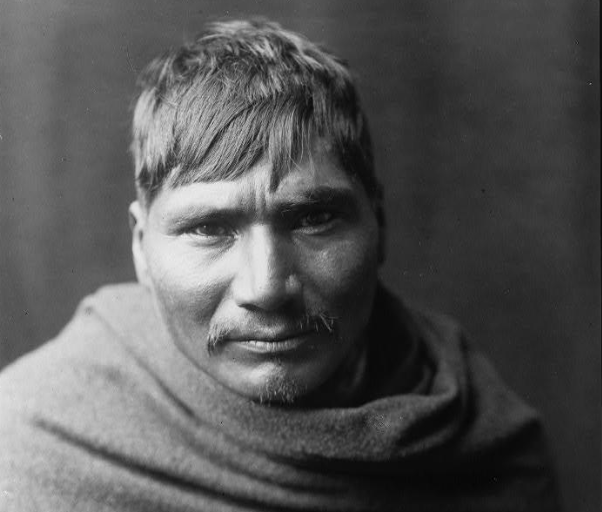

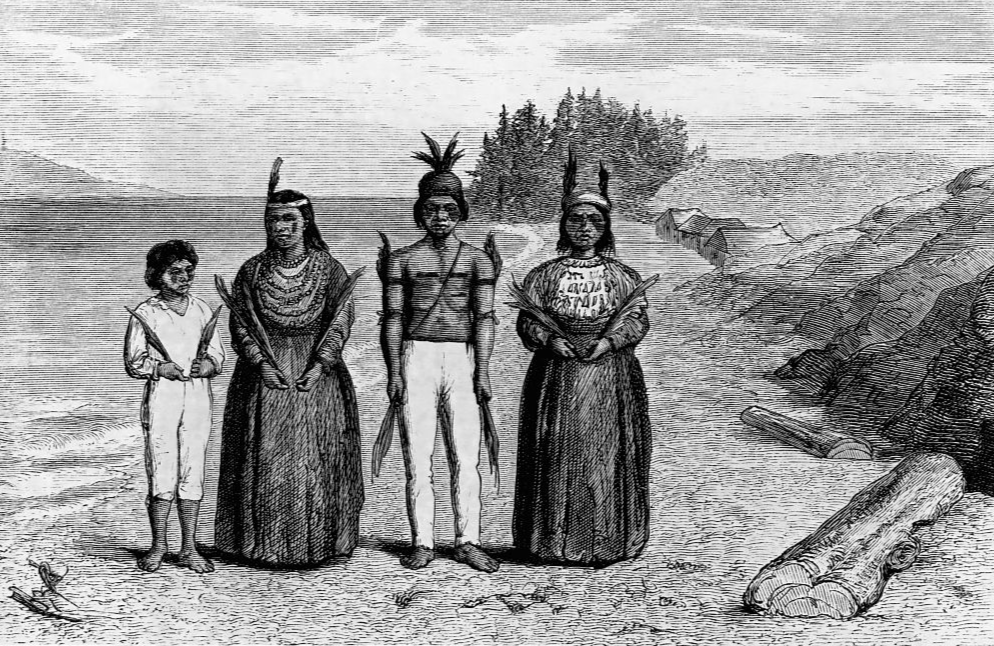

Their Beginning

Way back in the 16th century, the Yaqui tribe occupied a territory along the lower course of the Yaqui River, in Sonora, Mexico. At that time, they had about 30,000 people living in 80 villages in an area that was about 60 miles long and 15 miles wide. They were a peaceful tribe who lived harmoniously with nature, using the river as their primary life source. But, such as life, things would soon change.

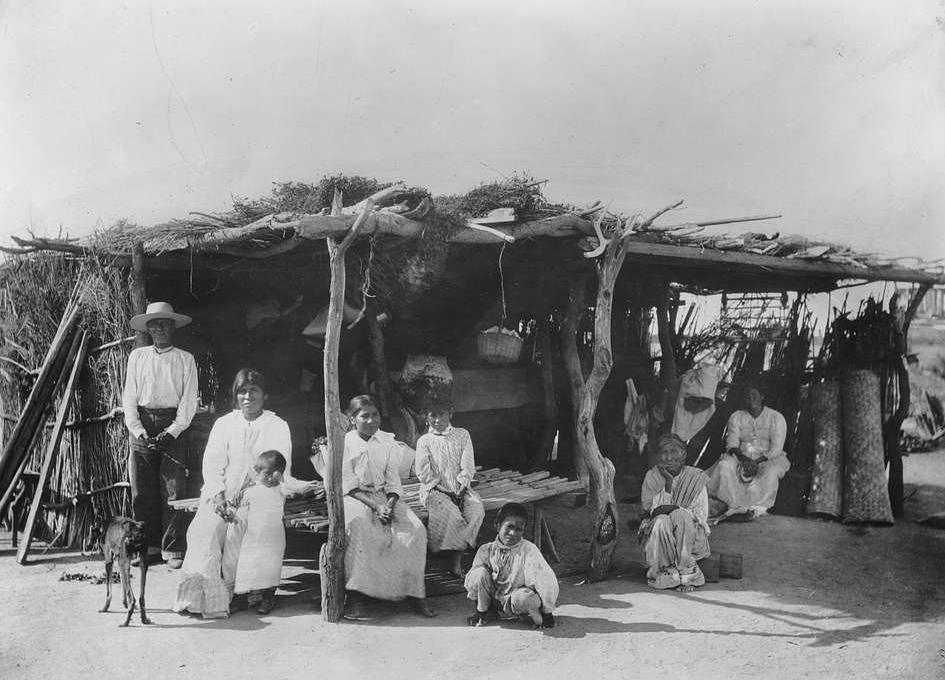

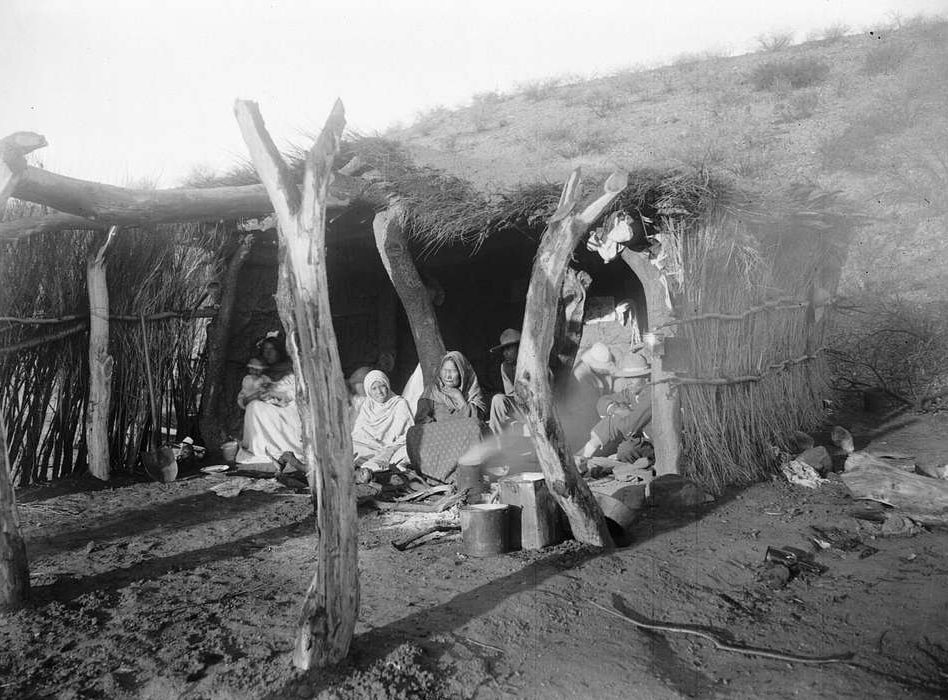

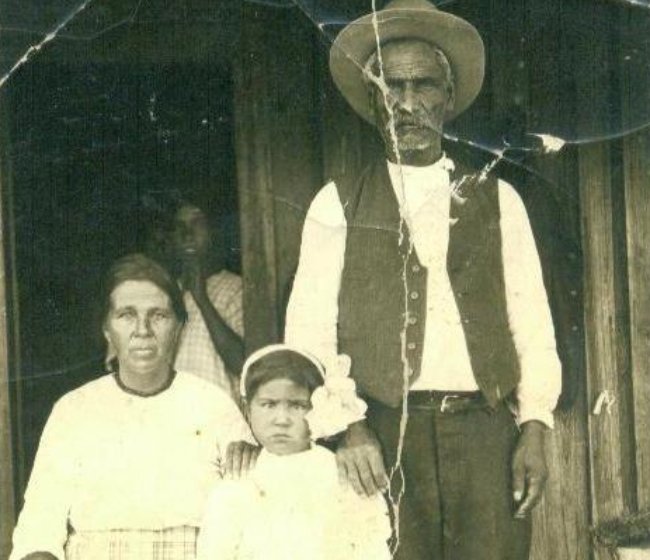

James, George Wharton, Wikimedia Commons

James, George Wharton, Wikimedia Commons

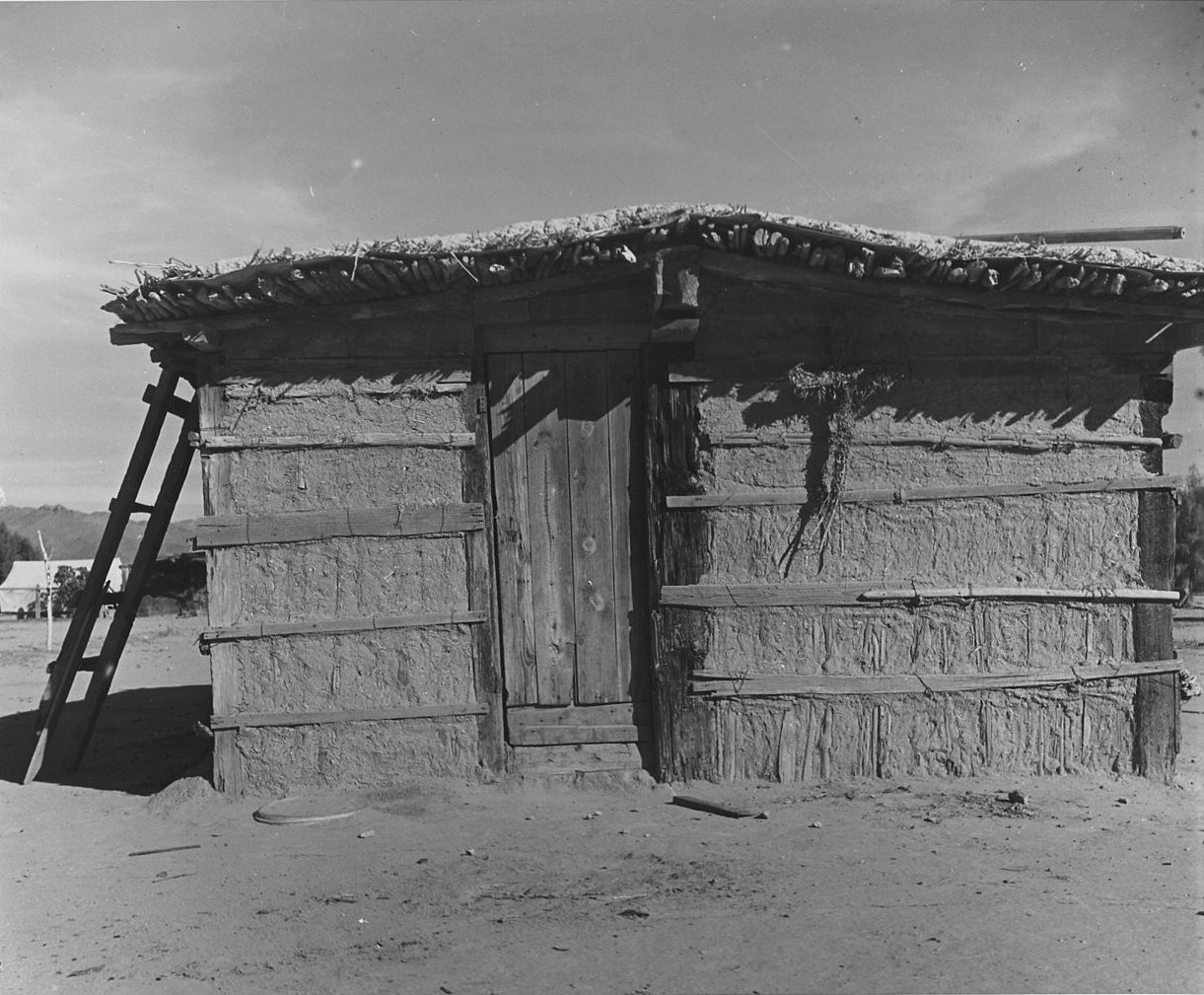

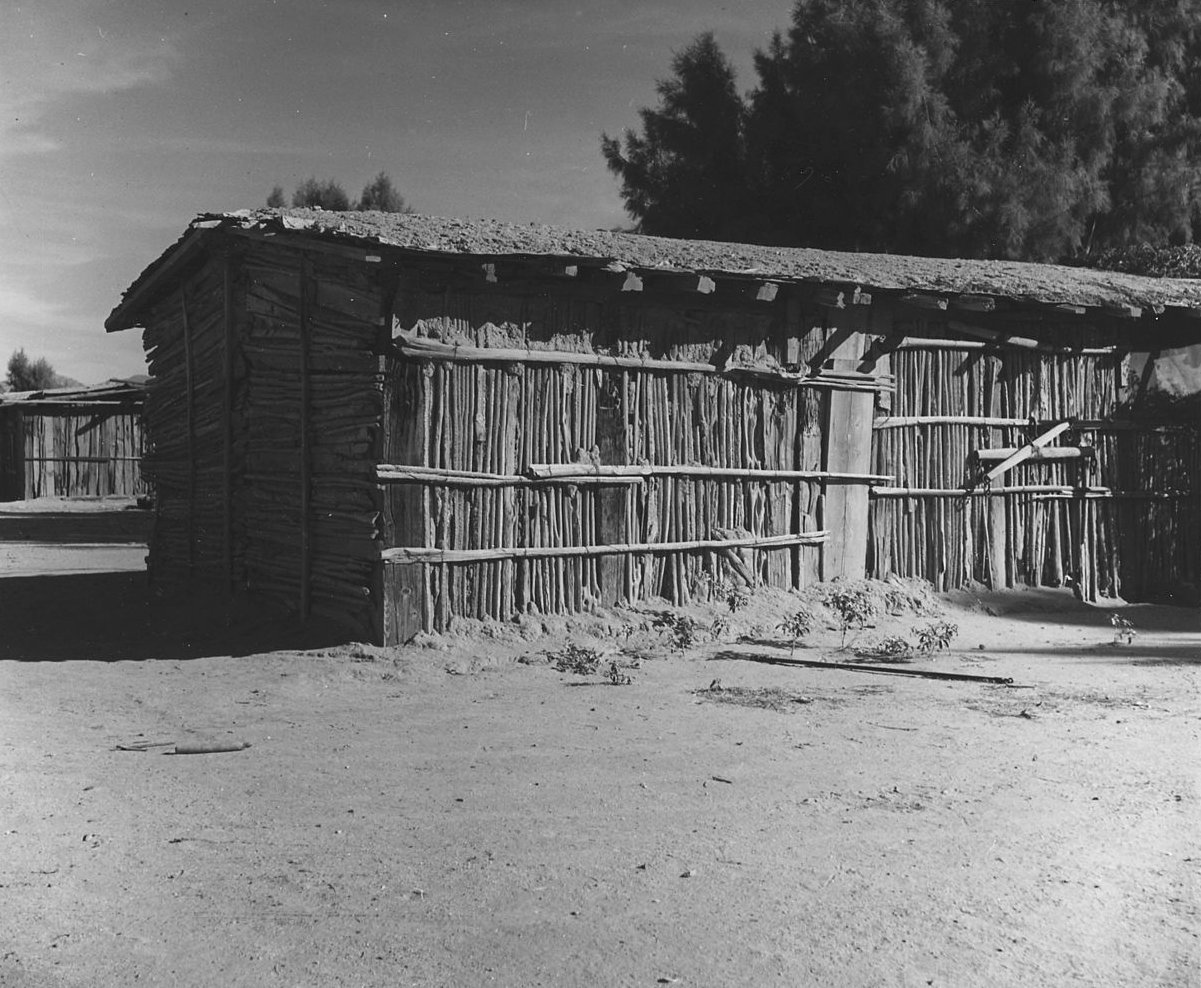

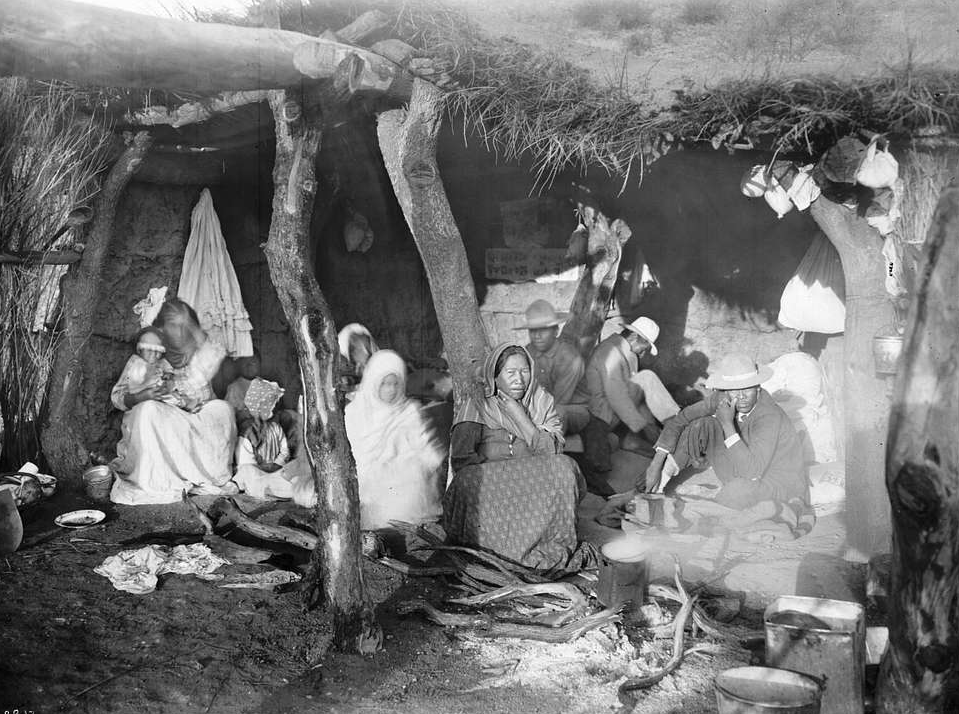

Their Homes

The Yaqui lived in traditional, hand-built houses made of adobe—which is clay and baked into hard bricks. The home typically had three sections: a bedroom, a kitchen, and a living room, called the “portal”. The floor was made of wooden supports, and the interior walls were made of woven reeds. The roof was made of reeds covered in thick mud for insulation—which was vital considering they lived in the hot desert.

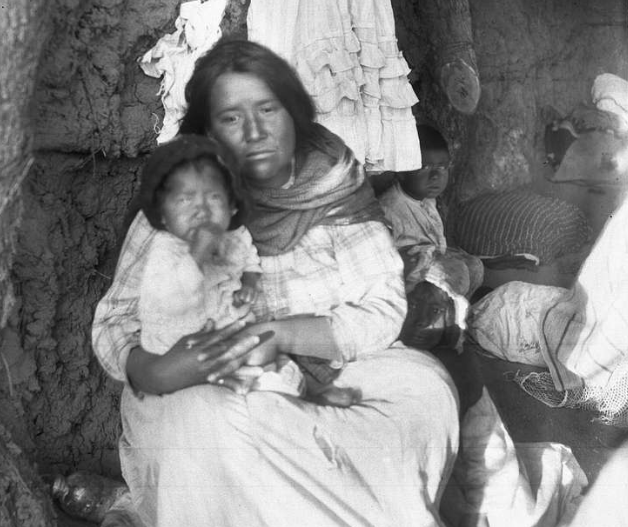

Dorothea Lange, Wikimedia Commons

Dorothea Lange, Wikimedia Commons

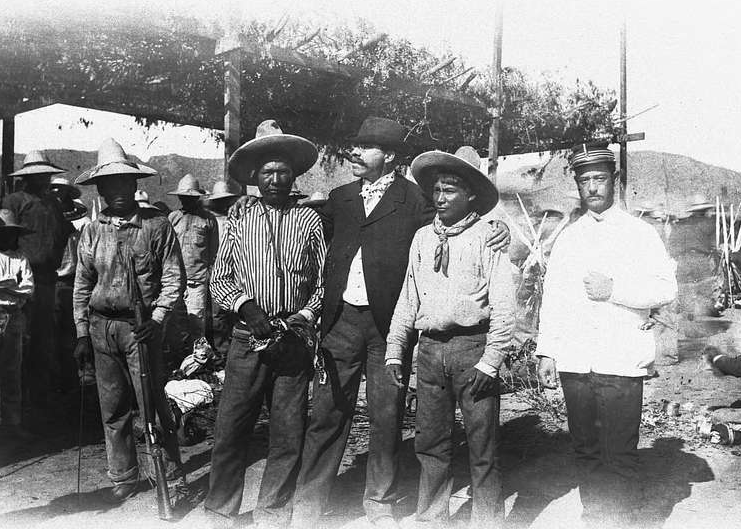

Their Lifestyle

This incredible ancient tribe were traditionally hunter-gatherers, who relied on their environment to survive. Some Yaqui lived along the mouth of the river, and lived off resources from the sea. Most lived in agricultural communities, growing beans, maize, and squash on land inundated by the river every year. Others lived in the deserts and mountains and depended upon hunting and gathering.

While the river sustained their food sources, the hot Mexican heat made it easier to clothe their bodies.

Dorothea Lange, Wikimedia Commons

Dorothea Lange, Wikimedia Commons

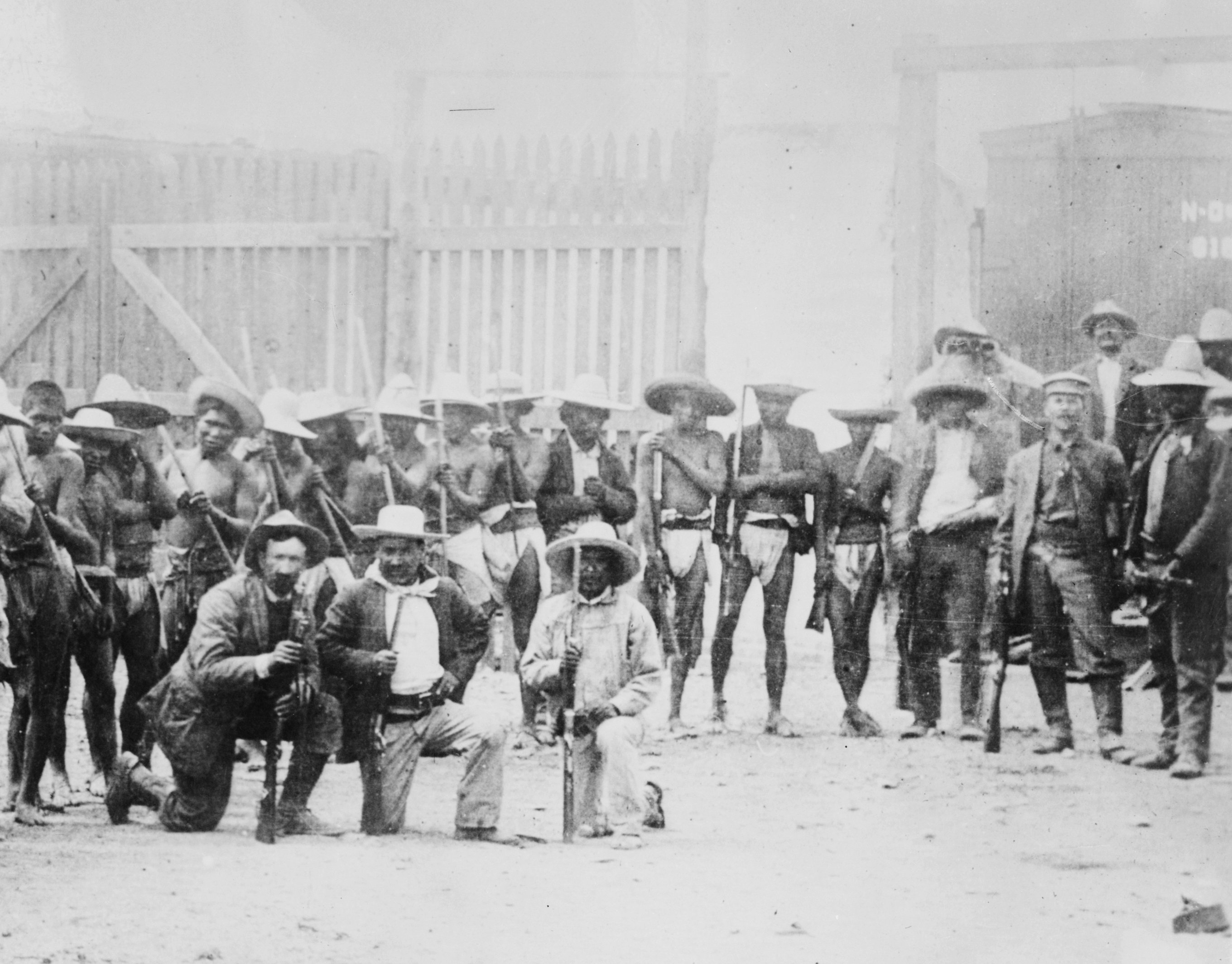

Their Clothing

Unlike Indigenous folk in the North, the harsh climate in Mexico required the Yaqui to wear less coverings, not more. In fact, the Yaqui people didn’t wear much clothing at all. The men wore only Native American breechcloths and sometimes leggings made of deerskin. Women wore knee-length skirts made of animal hide.

In the Yaqui culture, shirts were not necessary, but they sometimes wore rabbit-skin robes at night when temperatures were cooler. As for footwear, some wore deerskin moccasins, but others wore sandals made of yucca fiber—or simply went barefoot.

They were completely self-sustained and had a harmonious relationship with nature—that is, until an unwelcome visitor showed up.

Library of Congress, Getty Images

Library of Congress, Getty Images

The Spanish Arrival

In 1533, the Yaqui found themselves face-to-face with a group of foreign men. The leader of the group was Captain Diego de Guzman, a man belonging to the Spanish settlements just south of them—and he was looking for more land.

The Yaqui quickly assembled a large group of warriors and immediately went and confronted the Spaniards. Now, these Yaqui warriors were undoubtedly fierce, and they certainly had a reputation with other tribes as such, but they didn’t often go looking for trouble. At this point, they figured the group of outsiders simply didn’t know the boundaries, and a quick conversation would clear things up—sadly, they were wrong.

Anthony van Dyck, Wikimedia Commons

Anthony van Dyck, Wikimedia Commons

The Confrontation That Started It All

When they approached the newcomers, they saw a seemingly disturbing look in their eyes, and decided the best approach was to remain calm, collective—and stern. The Yaqui leader at the time, an elderly man dressed in a black tunic decorated with pearls and carvings made of wood and stone, simply walked up to his opposing leader, drew a line in the dirt and told the Spanish not to cross it.

He stood tall, put his hands behind his back, and took a step back—making sure not to break eye contact. Feeling good about his power, the Yaqui leader thought the situation was easily under control—but nothing could prepare him for what happened next.

Jusepe Leonardo, Wikimedia Commons

Jusepe Leonardo, Wikimedia Commons

They Were Disrespected

The Spaniards looked at each other and laughed, cracking jokes about the hand drawn boundary—delivering an intense disrespect to the Yaqui. To make matters worse, they then had the audacity to ask the Yaqui for food. They may or may not have been making a cruel joke, but either way they knew they weren’t settling for a line in the sand. So, when the Yaqui angrily shot down their ridiculous request for snacks, the Spaniards took things to the next level—instantly.

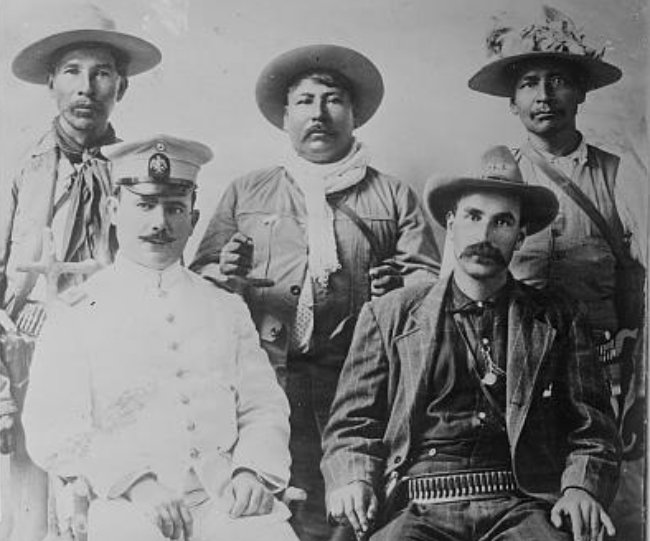

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

The First Of Many

Within minutes, both tribes suited up, and a bloody battle ensued. The Spanish ended up retreating, but still managed to claim victory somehow. The Yaqui suddenly lost a chunk of their land—and gained a new enemy. Thus, began the 40-year struggle for the Yaqui to protect their lands and their culture.

This may have been the Yaqui’s first experience with the Spanish—but it wouldn’t be their last.

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

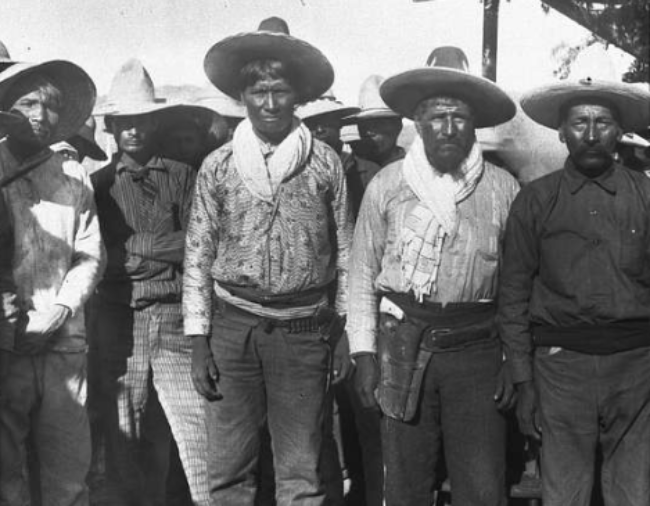

They Became The Resistance

The Yaqui were known as war-like people, full of pride and courage. They were also possibly the only native tribe in Mexico that resisted the crushing force of steel and gunpowder. They were considered to be "cunning as demons" by many of their rivals—and they would easily live up to their reputation.

While the Yaqui didn’t have guns, like their new-found enemy, they did have bows and arrows—and they were extremely skilled at using them. They also fought with spears and clubs. Not only did they have warrior skills, they had a warrior mindset that is credited for their stamina during battle—and their warrior-like nature came in handy when another Spanish leader came knocking.

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

Best Two Out Of Three

In 1565, Spanish Conquistador Francisco de Ibarra came in hot, with guns blazing. He attempted to establish a Spanish settlement in Yaqui territory, but ultimately, he failed. While he did lose a lot of men, and maybe a little of his pride, de Ibarra wasn’t actually interested in their land anyway. He was on a quest to find silver, and other precious metals—none of which was often found in the Yaqui territory. So, when de Ibarra lost the first two fights, he didn’t stick around for round 3. This is likely what saved the Yaqui from an early invasion—but that didn’t mean the war was over.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

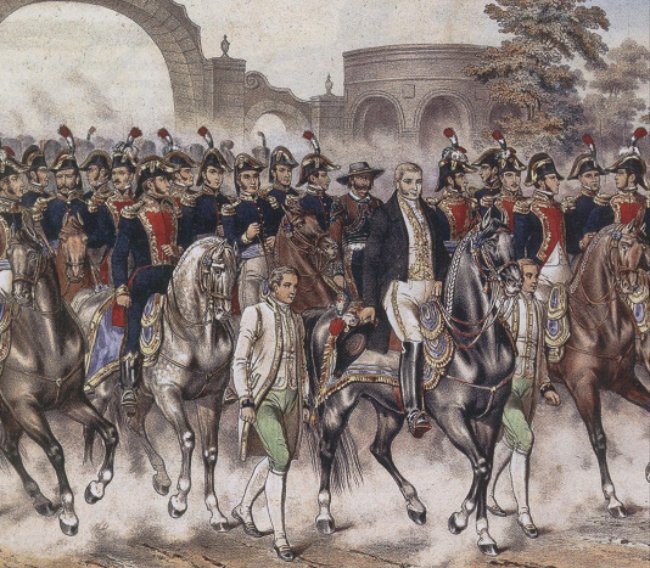

They Secured Their Reputation…And Their Land

After many small battles here and there, in 1608, the Yaqui and over 2,000 Indigenous allies, mostly Mayo, joined forces and ended up victorious over the Spanish in two separate, large-scale battles—securing their powerful reputation. After that, things got easier for the Yaqui.

In 1610, they signed a peace treaty agreeing to relinquish part of their land in exchange for a guarantee, signed by the King of Spain, acknowledging their ownership of their remaining territory in southern Sonora. At the time, they numbered between 100,000 and 200,000 people. Every Mexican government respected this treaty—until Porfirio Díaz came to power.

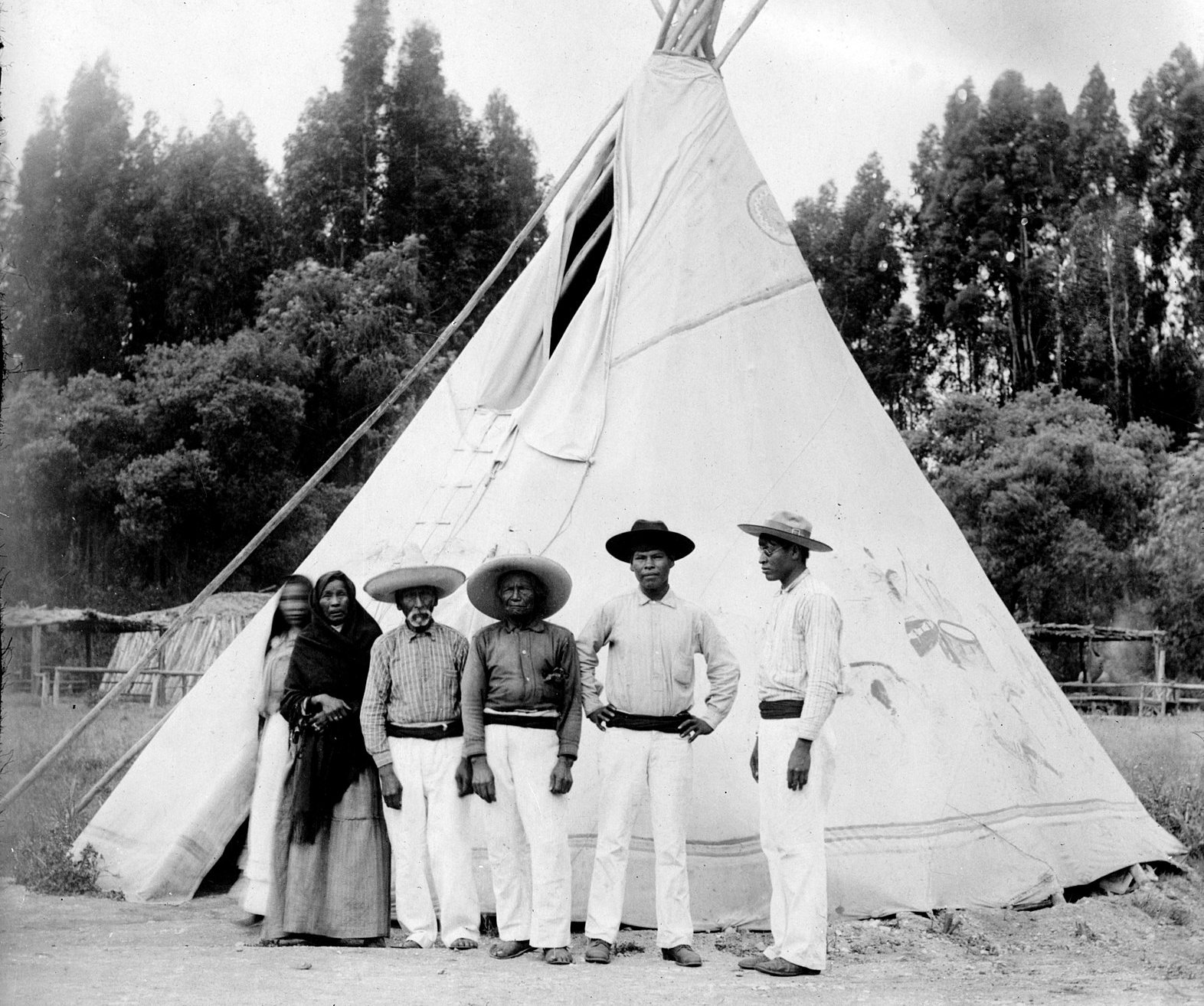

Aurelio Escobar Castellanos, Wikimedia Commons

Aurelio Escobar Castellanos, Wikimedia Commons

Welcoming The Jesuit Missionaries

But before Diaz, things did get easier. In 1617, the Yaqui actually invited the Jesuit missionaries to stay with them and teach them their ways. They lived in a mutually advantageous relationship with the Jesuits for over 120 years. And while they did mostly convert to Christianity, they also kept a large portion of their traditional beliefs and practices.

The Yaqui Religion is a syncretic religion (meaning, blended) of old Yaqui beliefs and practices and the Christian teachings of Jesuit missionaries. It’s also considered the earliest revitalization reform movement within Native American religions.

mideastimage, Wikimedia Commons

mideastimage, Wikimedia Commons

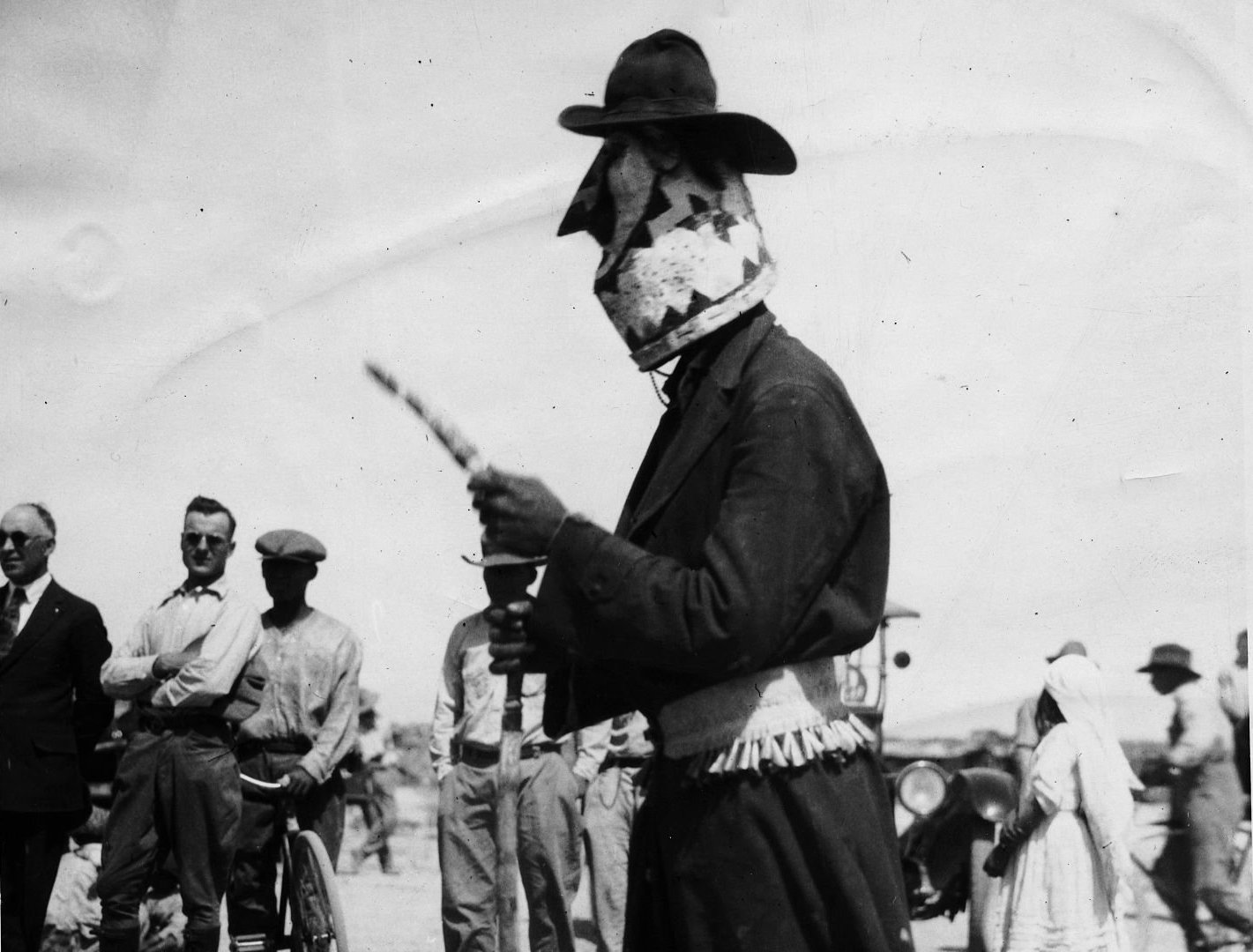

The Deer Dance

So, basically, the Yaqui pray to God, but they also rely heavily on song, music, and dancing performed by members of the community. They also continue to practice various traditional rituals and ceremonies, including the Deer Dance, which is performed during Lent and Easter especially.

The Deer Dance is extremely sacred, and thus, rarely photographed (today). It is said to have been held before a deer hunt, thanking the deer for his sacrifice so that the people may live—and it is very intricate.

The Deer Dance

Deer dancers, also called pahkolam, meaning “old men of the fiesta,” wear rattles around their ankles made from butterfly cocoons, honoring the insect world, and rattles from the hooves of deer around their waist, honoring the many deer who have died.

Instruments used in the dance include the water drum (which signifies the deer’s heartbeat), rasp (the deer’s breathing), gourd rattles held by the dancers (honoring the plant world), as well as the flute, fiddle, and frame harp, of Spanish influence. A specific deer song accompanies the dance.

If you can’t tell already, deer hold a special place in the Yaqui culture—and for good reason.

The Significance Of The Deer

For the Yaqui, the deer is a symbol of goodness. He (the deer) comes to the people and offers himself to them for their well-being. In turn, they use the deer for as much as possible, from food to clothing and even shelter and tools.

They also wear something called a Ojo de Venado (the “Deer Eye Necklace”) which is made out of a seed called Deer Eye, and is worn for physical and spiritual protection—something the Yaqui continued, even after the arrival of the missionaries.

Their Life Under The Jesuit Rule

The Jesuit rule over the Yaqui was stern but the Yaqui retained their land and their unity as a people. The Jesuits actually introduced the Yaqui to wheat, cattle, and horses. Prior to that, they were a hunter-gatherer tribe that were skilled at living off the land—which is no easy feat for a hot, sandy desert.

Using their intimate knowledge of the Sonoran Desert landscape, the Yaqui traditionally farmed the “three sisters” crops of corn, beans, and squash, as well as to cotton. Yaqui men hunted deer, rabbits, and small game, and sometimes fished in the Gulf of Mexico. The women gathered nuts, fruits, and herbs. They continued this lifestyle even after the Jesuits had introduced them to other options.

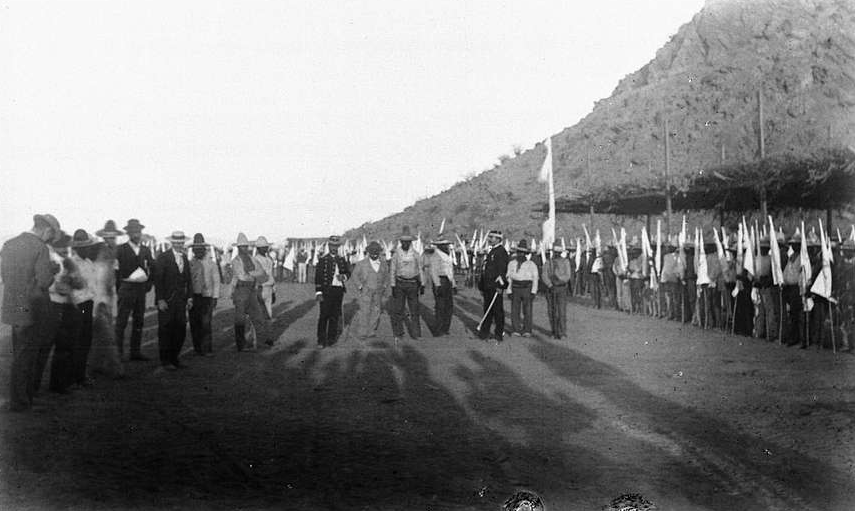

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

They Had A Short-Lived Prosperity

At this time, the Yaqui were prospering and so they allowed the missionaries to extend their activities further north. It’s likely that the Yaqui trusted the Jesuits so much because the nearest Spanish settlement was over 100 miles away, which meant that conflict was easily avoided—or so they thought.

By the 1730s, Spanish settlers and miners were getting closer and had begun encroaching on Yaqui land. At the same time, the Spanish colonial government started making sly changes to the arms-length relationship. Understandably upset about this, the Yaqui and Mayo revolted in 1740—and the outcome was brutal.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

The 1740 Revolt

The 1740 revolt was brief but bloody. 1,000 Spaniards and 5,000 Native Americans were killed—and the animosity lingered. Instantly, the Jesuit missionaries became nervous and started pulling out, and the Yaqui prosperity of the earlier years hit a brick wall.

By 1767, the Jesuits left Mexico entirely and the Franciscan priests who replaced them never gained the confidence of the Yaqui. An uneasy peace between the Spaniards and the Yaqui endured for many years after the revolt—but then in 1821, everything changed.

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

With Independence Comes…Taxes

Finally, in 1821, the Spaniards took off with their tails between their legs. Their 11-year battle ended when Spain signed a treaty formally recognizing Mexico’s independence. But to the Yaqui, this didn’t mean squat. They still considered themselves independent and self-governing. So, when the new Mexican government came after them for taxes, they refused—and once again, things got messy.

They Devised A Plan Of Their Own

In 1825, Yaqui leader Juan Banderas led a revolt, with hopes of uniting the Mayo, Opata, Pima, and Yaqui into a state that would be independent of Mexico. Together, the tribes fought tirelessly and after more bloody battles, they successfully drove the Mexicans out of their territories. Unfortunately, their celebration was short-lived as the Yaqui leader was eventually defeated and executed in 1833.

However, this only fueled the fire, and a succession of revolts continued as the Yaqui resisted all control from the Mexican government. The war featured a number of awful brutalities by Mexican authorities, including a massacre in 1868, in which the Army tragically burned 150 Yaqui to death inside a church.

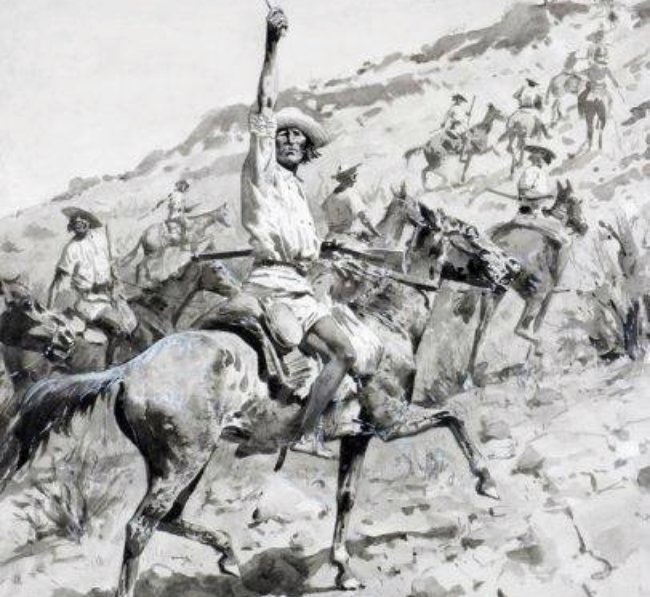

Frederic Remington, Wikimedia Commons

Frederic Remington, Wikimedia Commons

They Fled To The Mountains

This went on for the full rule of the next Yaqui leader, known as Cajemé, until he was executed in 1887. At that point, the Mexican government changed up their policies and started confiscating Yaqui lands, displacing hundreds of Yaqui. Some of them fled to the mountains where they joined guerilla campaigns against the Mexican Army. Then, in 1876, Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz entered the picture—and things went from bad to worse.

Fernando Llaguno, Wikimedia Commons

Fernando Llaguno, Wikimedia Commons

The Brutal Reign Of Diaz

Under Diaz’s rule, the Mexican government didn’t just confiscate the Yaqui land, they brutalized and harassed the Yaqui people to no end. They harassed them, stole their belongings, and set their homes on fire. They even took their best lands and gave it to their own leaders to live on. Thousands of Yaqui were taken as hostages and then sold as slaves to sugar cane and tobacco plantations.

Many Yaqui had managed to escape, but were too far from home to even dream of making it back. Without any help, anyone who managed to free themselves ended up succumbing to starvation or violence along the way.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

They Upgraded Their Artillery

It was during these war-torn years that the Yaqui upgraded their weapons and were now fighting back with pieces similar to that of their enemies. But in 1898, the government troops got their hands on new and improved rifles that, sadly, were no match for what the Yaqui had. With most of their people being enslaved already, the Yaqui’s surrender was imminent.

By this time, soldiers were hunting down Yaqui like vermin—especially when the prize was upped to $100 for the ears of a Yaqui guerilla. Even with a bounty on their heads, though, the Yaqui continued to fight, and they put up a good one, too—just not good enough. The worst was yet to come.

Their Hell On Earth

After the government’s army failed to secure a “handful of renegades,” President Diaz ordered a full sweeping of all living Yaqui—including women and children. They were put onto boats and shipped to San Blas, where a brutal and treacherous journey awaited them.

The thousands of captured Yaqui were forced to walk more than 200 miles to San Marcos and its train station. The walk took several weeks, in which many women and young children did not survive. Their bodies were left by the side of the road to become food for the wildlife. And those who survived the walk wished they hadn’t.

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

They Were Thrown Into Concentration Camps

Once they got to their destination, the Yaqui were separated from their loved ones. Children were ripped from their mother’s arms. They were thrown into concentration camps before being stuffed into boxcars and stinking holds of ships. After some travel, they were then forced to walk once more—a dreadful trek across 200 miles through Mexico’s roughest mountains. Many of those who survived up until this point ended up perishing from brutal falls down unforgiving cliffs, starvation, and pure exhaustion. Anyone who made it past this, had another disturbing fate waiting for them.

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

Their Survivors Became Slaves

Survivors were sold to plantations as slaves, where they lived the days working physical labor in the brutal heat, from dusk until dawn. They were given very little food and were beaten if they didn’t meet their nearly impossible quotas. They spent their nights locked up, alone and cold. Most Yaqui who were sent to plantations died there—with two-thirds of them dying within the first year. But the most brutal treatment of all was what happened to the Yaqui women.

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

Thinning Out Their Bloodlines

Yaqui women were forced to marry and mate with non-native Chinese workers (who were also enslaved against their will). Each week, the female Yaqui slaves were taken out and forced to choose husbands from among the male Chinese slaves. After several refusals, one was chosen for them. Those who resisted were severely beaten.

Many people believe this atrocity was not only a form of punishment, but also a way to annihilate them altogether. Why else would they separate women from their husbands and force them to bear children for men of a different cultural and ethnic background?

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

They Refused To Give Up

While all this was happening, the Yaqui resistance continued. They never fully surrendered. Instead, some of them fled to Arizona, where they would end up working and earning money in the US—though they had an ulterior motive. Most Yaqui who went to Arizona would get their hands on firearms and ammunition, and then smuggle it home to the Yaqui who were still fighting the Mexican government.

The objective of the Yaqui and the Mayo remained the same for nearly 400 years: to manage their own lands. And while it seemed like they might actually do it—1927 had other plans.

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

They Fought One Last Time

The last major battle between the Mexican Army and the Yaqui occurred in 1927 and was fought at Cerro del Gallo Mountain. Unfortunately, the Mexican Army’s heavy artillery and planes were no match for the Yaqui, and the Mexican authorities eventually prevailed.

But it wasn’t the end just yet. About 10 years later, things took a drastic turn.

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

They Won

In 1937, General Lázaro Cárdenas—who had previously defeated the Yaqui back in 1917—was now the president of the republic, and was making some big changes.

General Cárdenas decided to reserve 500,000 hectares of ancestral lands on the north bank of the Yaqui River for the Yaqui to once again call home. He also ordered the construction of a dam to provide irrigation water to the Yaqui, and gave them advanced agricultural equipment and water pumps to aid in their lifestyle.

Believe it or not, after centuries of horrific battle, the Yaqui were able to maintain a degree of independence from Mexican rule—and finally, they were able to pick up the pieces of all that they had lost.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Their Population Started To Grow

According to the official government report on the sexenio (six-year term) of Cárdenas, the section of the Department of Indigenous Affairs (which Cárdenas established as a cabinet-level post in 1936) stated the Yaqui population was back up to 10,000, with 3,000 being children younger than five. And their population wasn’t the only thing that grew.

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

They Made A Comeback

In 1939, the Yaqui reportedly produced 3,500 tons of wheat, 500 tons of maize, and 750 tons of beans; whereas, only two years prior, in 1935, they had produced only 250 tons of wheat and no maize or beans.

Their numbers all around were increasing, and the Yaqui were slowly getting their life back. Little did they know, it would never go back to the way it was.

Hiakiyoeme, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Hiakiyoeme, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Lost Their Biggest Natural Resource

As we know, the Yaqui live in the hot Sonoran Desert, which happens to be the hottest desert in both Mexico and the US. This means that they greatly depend on the Yaqui River for their survival. But after decades of war, the Yaqui have now found themselves having to fight for water rights. The water was supposed to be for them, in their territory, which was agreed upon many years ago. But instead, the water is being looted (unlawfully redirected to other areas), and the river is not being maintained. Droughts and dams have caused a large portion of the Yaqui River to dry up—posing a serious threat to the Yaqui culture.

panza.rayada, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

panza.rayada, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

They’re Losing Their Culture

Aside from no longer having water for drinking and agriculture, the lack of available water has also led to a drastic decline in plant and tree species, specifically the alamo and the giant reed—both of which are used to build traditional structures in Yaqui villages.

It has also threatened the survival of the “four mirror butterfly,” an endemic moth species that depends on the Yaqui River and is central to the Yaqui ritual dance. Because of this drastic change in their environment, the Yaqui tribe is slowly losing their culture.

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

They Went From Pottery To Plastic

Before all of this war and attempted exterminations, the Yaqui people would happily hike to the river and fill their handmade pottery with deliciously fresh water to bring back to their village. Now, they have to buy water that is not only imported in plastic containers—it’s rationed. And that’s not the only thing that changed about their home.

While they did get some of their land back, it wasn’t exactly given back in the same state. Aside from a drastic change to their natural resources, nearly all of the Yaqui’s traditional villages were burned down and looted. They quite literally had nothing left. And now, decades later, they’re living in a whole new world.

California Historical Society, Picryl

California Historical Society, Picryl

They Were Told It Would Be Easier

The Mexican government may have given back their land, but it wasn’t just simply handed over. Their ancestral villages no longer existed. Instead, the Yaqui were given reservations—lands appointed to them. Some of these reservations were set up in Arizona, far from their homeland—and far from traditional life.

In some of the reservations, their traditional adobe huts were replaced by concrete structures. Their colorful embroidered skirts were replaced with jeans. Suddenly, there was no need to make their own possessions. Everything was created in the factories of the modern world. They were told this would make their lives “easier”.

And while many Yaqui were somewhat open to this new world—something didn’t sit right with the elders.

They Refused To Participate

The Yaqui today remain independent—not just from the Mexican government, but as individuals themselves. While some Yaqui choose to live on the modern reserves of Arizona, many Yaqui have chosen to live as traditionally as possible in Mexico, bringing back as much of their historical culture as possible—and emphasizing the independence they fought so hard for.

Today, there are eight Yaqui villages in Sonora, with their primary homeland in Río Yaqui Valley. Some of these villages are more on the modern-side, while others boast traditional adobe housing—complete with a lack of electricity and modern technology.

Pierce, Charles C., Wikimedia Commons

Pierce, Charles C., Wikimedia Commons

They Kept Their Traditions

And while their traditional lifestyle may be different, the Yaqui continue to dabble in their traditional arts and crafts—something their culture is particularly famous for. Yaqui artists have always been known for their beautiful mask carvings, which are used for a variety of purposes, including religious ceremonies, plays, and cultural events. They also make beaded necklaces, stone carvings, and stunning woven blankets.

But their handicrafts are not the only ancestral tradition they try to keep.

They Stay Committed To Their Culture

Yaqui today still keep up with traditional gender roles as well. Women have always played an integral role in planting, harvesting, and processing food. They would often grind corn into flour, which would then be used to make flatbreads and cakes—a practice that is still common in the Yaqui kitchen today. Women continue to weave baskets, make pottery, and care for the family’s living spaces.

And while the men remain responsible for bringing home the bacon, they are also known to be the keepers of oral history—something they have learned is extremely important if they plan to keep their culture alive.

Ministry of Culture of Mexico City, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ministry of Culture of Mexico City, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Never Surrendered

The Yaqui are noteworthy in their struggle to preserve their autonomy and traditions. They are known for having waged the most determined, enduring, and successful resistance against involuntary absorption into the dominant culture of the Spanish, Catholic, and Mexican society.

In fact, they’re the only Native American tribe that has never officially surrendered to either the Spanish colonial forces, the Mexican government, or the United States.

Francisco Antonio Carrillo Huez, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Francisco Antonio Carrillo Huez, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Their Culture Survived

While they still have a long way to go in terms of fighting for their rights (particularly water rights and education rights), the most recent consensus puts the Yaqui population in Mexico at about 16,240, and close to 22,400 in Arizona. This may be a sadly reduced number, but in spite of everything, their culture survived.